Purpose and Need

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baja California, Mexico, and a Vegetation Map of Colonet Mesa Alan B

Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany Volume 29 | Issue 1 Article 4 2011 Plants of the Colonet Region, Baja California, Mexico, and a Vegetation Map of Colonet Mesa Alan B. Harper Terra Peninsular, Coronado, California Sula Vanderplank Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden, Claremont, California Mark Dodero Recon Environmental Inc., San Diego, California Sergio Mata Terra Peninsular, Coronado, California Jorge Ochoa Long Beach City College, Long Beach, California Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso Part of the Biodiversity Commons, Botany Commons, and the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons Recommended Citation Harper, Alan B.; Vanderplank, Sula; Dodero, Mark; Mata, Sergio; and Ochoa, Jorge (2011) "Plants of the Colonet Region, Baja California, Mexico, and a Vegetation Map of Colonet Mesa," Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany: Vol. 29: Iss. 1, Article 4. Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso/vol29/iss1/4 Aliso, 29(1), pp. 25–42 ’ 2011, Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden PLANTS OF THE COLONET REGION, BAJA CALIFORNIA, MEXICO, AND A VEGETATION MAPOF COLONET MESA ALAN B. HARPER,1 SULA VANDERPLANK,2 MARK DODERO,3 SERGIO MATA,1 AND JORGE OCHOA4 1Terra Peninsular, A.C., PMB 189003, Suite 88, Coronado, California 92178, USA ([email protected]); 2Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden, 1500 North College Avenue, Claremont, California 91711, USA; 3Recon Environmental Inc., 1927 Fifth Avenue, San Diego, California 92101, USA; 4Long Beach City College, 1305 East Pacific Coast Highway, Long Beach, California 90806, USA ABSTRACT The Colonet region is located at the southern end of the California Floristic Province, in an area known to have the highest plant diversity in Baja California. -

Field Release of the Hoverfly Cheilosia Urbana (Diptera: Syrphidae)

USDA iiillllllllll United States Department of Field release of the hoverfly Agriculture Cheilosia urbana (Diptera: Marketing and Regulatory Syrphidae) for biological Programs control of invasive Pilosella species hawkweeds (Asteraceae) in the contiguous United States. Environmental Assessment, July 2019 Field release of the hoverfly Cheilosia urbana (Diptera: Syrphidae) for biological control of invasive Pilosella species hawkweeds (Asteraceae) in the contiguous United States. Environmental Assessment, July 2019 Agency Contact: Colin D. Stewart, Assistant Director Pests, Pathogens, and Biocontrol Permits Plant Protection and Quarantine Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service U.S. Department of Agriculture 4700 River Rd., Unit 133 Riverdale, MD 20737 Non-Discrimination Policy The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination against its customers, employees, and applicants for employment on the bases of race, color, national origin, age, disability, sex, gender identity, religion, reprisal, and where applicable, political beliefs, marital status, familial or parental status, sexual orientation, or all or part of an individual's income is derived from any public assistance program, or protected genetic information in employment or in any program or activity conducted or funded by the Department. (Not all prohibited bases will apply to all programs and/or employment activities.) To File an Employment Complaint If you wish to file an employment complaint, you must contact your agency's EEO Counselor (PDF) within 45 days of the date of the alleged discriminatory act, event, or in the case of a personnel action. Additional information can be found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_file.html. To File a Program Complaint If you wish to file a Civil Rights program complaint of discrimination, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form (PDF), found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html, or at any USDA office, or call (866) 632-9992 to request the form. -

Vascular Plants of Santa Cruz County, California

ANNOTATED CHECKLIST of the VASCULAR PLANTS of SANTA CRUZ COUNTY, CALIFORNIA SECOND EDITION Dylan Neubauer Artwork by Tim Hyland & Maps by Ben Pease CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY, SANTA CRUZ COUNTY CHAPTER Copyright © 2013 by Dylan Neubauer All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without written permission from the author. Design & Production by Dylan Neubauer Artwork by Tim Hyland Maps by Ben Pease, Pease Press Cartography (peasepress.com) Cover photos (Eschscholzia californica & Big Willow Gulch, Swanton) by Dylan Neubauer California Native Plant Society Santa Cruz County Chapter P.O. Box 1622 Santa Cruz, CA 95061 To order, please go to www.cruzcps.org For other correspondence, write to Dylan Neubauer [email protected] ISBN: 978-0-615-85493-9 Printed on recycled paper by Community Printers, Santa Cruz, CA For Tim Forsell, who appreciates the tiny ones ... Nobody sees a flower, really— it is so small— we haven’t time, and to see takes time, like to have a friend takes time. —GEORGIA O’KEEFFE CONTENTS ~ u Acknowledgments / 1 u Santa Cruz County Map / 2–3 u Introduction / 4 u Checklist Conventions / 8 u Floristic Regions Map / 12 u Checklist Format, Checklist Symbols, & Region Codes / 13 u Checklist Lycophytes / 14 Ferns / 14 Gymnosperms / 15 Nymphaeales / 16 Magnoliids / 16 Ceratophyllales / 16 Eudicots / 16 Monocots / 61 u Appendices 1. Listed Taxa / 76 2. Endemic Taxa / 78 3. Taxa Extirpated in County / 79 4. Taxa Not Currently Recognized / 80 5. Undescribed Taxa / 82 6. Most Invasive Non-native Taxa / 83 7. Rejected Taxa / 84 8. Notes / 86 u References / 152 u Index to Families & Genera / 154 u Floristic Regions Map with USGS Quad Overlay / 166 “True science teaches, above all, to doubt and be ignorant.” —MIGUEL DE UNAMUNO 1 ~ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ~ ANY THANKS TO THE GENEROUS DONORS without whom this publication would not M have been possible—and to the numerous individuals, organizations, insti- tutions, and agencies that so willingly gave of their time and expertise. -

Proposed Rule for 16 Plant Taxa from the Northern Channel Islands

Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 142 / Tuesday, July 25, 1995 / Proposed Rules 37993 Fish and Wildlife Service, Ecological Final promulgation of the regulations Carlsbad Field Office (see ADDRESSES Services, Endangered Species Permits, on these species will take into section). 911 N.E. 11th Avenue, Portland, Oregon consideration the comments and any Author. The primary author of this 97232±4181 (telephone 503/231±2063; additional information received by the document is Debra Kinsinger, Carlsbad Field facsimile 503/231±6243). Service, and such communications may Office (see ADDRESSES section). lead to a final regulation that differs Public Comments Solicited List of Subjects in 50 CFR Part 17 from this proposal. The Service intends that any final The Endangered Species Act provides Endangered and threatened species, action resulting from this proposal will for one or more public hearings on this Exports, Imports, Reporting and be as accurate and as effective as proposal, if requested. Requests must be recordkeeping requirements, and possible. Therefore, comments or received by September 25, 1995. Such Transportation. suggestions from the public, other requests must be made in writing and concerned governmental agencies, the addressed to the Field Supervisor of the Proposed Regulation Promulgation scientific community, industry, or any Carlsbad Field Office (see ADDRESSES Accordingly, the Service hereby other interested party concerning this section). proposes to amend part 17, subchapter proposed rule are hereby solicited. National Environmental Policy Act B of chapter I, title 50 of the Code of Comments particularly are sought Federal Regulations, as set forth below: concerning: The Fish and Wildlife Service has (1) Biological, commercial trade, or determined that Environmental PART 17Ð[AMENDED] other relevant data concerning any Assessments or Environmental Impact threat (or lack thereof) to Sibara filifolia, Statements, as defined under the 1. -

![Environmental Assessment for HUD-Funded Proposals Recommended Format Per 24 CFR 58.36, Revised March 2005 [Previously Recommended EA Formats Are Obsolete]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6838/environmental-assessment-for-hud-funded-proposals-recommended-format-per-24-cfr-58-36-revised-march-2005-previously-recommended-ea-formats-are-obsolete-1796838.webp)

Environmental Assessment for HUD-Funded Proposals Recommended Format Per 24 CFR 58.36, Revised March 2005 [Previously Recommended EA Formats Are Obsolete]

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development San Francisco Regional Office - Region IX 600 Harrison Street San Francisco, California 94107-1387 www.hud.gov espanol.hud.gov Environmental Assessment for HUD-funded Proposals Recommended format per 24 CFR 58.36, revised March 2005 [Previously recommended EA formats are obsolete]. Project Identification: Winterhaven Public Safety Facility Preparer: Kevin L. Grant, Ericsson-Grant, Inc. Responsible Entity: County of Imperial Month/Year: February/2017 1 Environmental Assessment Responsible Entity:_County of Imperial___ _____________________________________ [24 CFR 58.2(a)(7)] Certifying Officer:_Ralph Cordova, Jr. ___ ______________________________________ [24 CFR 58.2(a)(2)] Project Name: Winterhaven Public Safety Facility____________________________________ Project Location: 518 Railroad Avenue, Winterhaven, CA 92281________________________ Estimated total project cost: $2,870,446__________________________________________ Grant Recipient County of Imperial_______________________________________________ [24 CFR 58.2(a)(5)] Recipient Address: 940 W. Main Street, Suite 208, El Centro, CA 92243 Project Representative: Esperanza Colio Warren, Community & Economic Development Manager Telephone Number: (442) 265-1100 Conditions for Approval: (List all mitigation measures adopted by the responsible entity to eliminate or minimize adverse environmental impacts. These conditions must be included in project contracts and other relevant documents as requirements). [24 CFR 58.40(d), 40 CFR 1505.2(c)] Mitigation Measure AQ-1: During clearing, grading, earth moving, or excavation operations, excessive fugitive dust emissions shall be controlled by the following techniques: Prepare a high wind dust control plan and implement plan elements and terminate soil disturbance when winds exceed 25 mph. Limit the simultaneous disturbance area to as small an area as practical when winds exceed 25 mph. -

POLLEN MORPHOLOGY of the LEONTODONTINAE (ASTERACEAE Rlactuceae)

POLLEN MORPHOLOGY OF THE LEONTODONTINAE (ASTERACEAE rLACTUCEAE) by KATHLEEN J. ZELEZNAK B.S., Kansas State University, 1975 A MASTER'S THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree MASTER OF SCIENCE Division of Biology KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 1978 Approved by: Ma j o r T" c o f e s sor '•^ TABLE OF CONTENTS *z,Hh Pa e c . 3l § Introduction 1 Literature Review 2 Materials and Methods 11 Results 20 Exomorphology 20 Endoroorphology 52 Discussion 70 References gft LIST OF FIGURES Figure Page 1 Lactuceae Pollen Diagram 7 2 Leontodontinae Endomorphology 9 3 Method of Measuring Pollen in LM 14 4- 5 SEM micrographs of pollen grains of Rhagadiolus stellatus 26 6 SEM micrograph of a pollen grain of Aposeris f oetida 26 7 SEM micrograph of a pollen grain of Hycs^ris radiata s. radiat a ~ 26 8- 9 SEM micrographs of pollen grains of Hedypnois cretica 26 10 SEM micrograph of a pollen grain of Aposeris foetida 26 11-12 SEM micrographs of pollen grains of Hyoseris radiata s. radia ta 26 13-17 SEM micrographs of pollen grains of Hedypnois c retica 28 18 SEM micrograph of a pollen grain of Hedypnois raonspeliensis 28 19-21 SEM micrographs of pollen grains of Garhadiolus hedypno is 28 22 SEM micrograph of a pollen grain of Hypochoeris radicata 37 23-24 SEM micrographs of pollen grains of Hypochoeris glabra 37 25 SEM micrograph of a pollen grain of Hypochoeris achyrophorous 37 26-27 SEM micrographs of pollen grains of Hypochoeris uniflora 37 28 SEM micrograph of a pollen grain of Hypochoeris cretensis 37 29-30 SEM micrographs of pollen grains of Hypochoeris grandiflora 37 31-32 SEM micrographs of pollen grains of Hypochoeris tenuif_olia 39 33-34 SEM micrographs of pollen grains of Hypochoeris hohenackeri 39 35 SEM micrograph of a pollen grain of Hypochoeris arenaria v. -

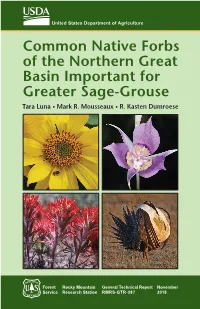

Common Native Forbs of the Northern Great Basin Important for Greater Sage-Grouse Tara Luna • Mark R

United States Department of Agriculture Common Native Forbs of the Northern Great Basin Important for Greater Sage-Grouse Tara Luna • Mark R. Mousseaux • R. Kasten Dumroese Forest Rocky Mountain General Technical Report November Service Research Station RMRS-GTR-387 2018 Luna, T.; Mousseaux, M.R.; Dumroese, R.K. 2018. Common native forbs of the northern Great Basin important for Greater Sage-grouse. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-387. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station; Portland, OR: U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management, Oregon–Washington Region. 76p. Abstract: is eld guide is a tool for the identication of 119 common forbs found in the sagebrush rangelands and grasslands of the northern Great Basin. ese forbs are important because they are either browsed directly by Greater Sage-grouse or support invertebrates that are also consumed by the birds. Species are arranged alphabetically by genus and species within families. Each species has a botanical description and one or more color photographs to assist the user. Most descriptions mention the importance of the plant and how it is used by Greater Sage-grouse. A glossary and indices with common and scientic names are provided to facilitate use of the guide. is guide is not intended to be either an inclusive list of species found in the northern Great Basin or a list of species used by Greater Sage-grouse; some other important genera are presented in an appendix. Keywords: diet, forbs, Great Basin, Greater Sage-grouse, identication guide Cover photos: Upper le: Balsamorhiza sagittata, R. -

Thirteen Plant Taxa from the Northern Channel Islands Recovery Plan

Thirteen Plant Taxa from the Northern Channel Islands Recovery Plan I2 cm Illustration of island barberry (Berberis pinnata ssp. insularis). Copyright by the Regents of the University of California, reproduced with permission of the Jepson Herbarium, University of California. THIRTEEN PLANT TAXA FROM THE NORTHERN CHANNEL ISLANDS RECOVERY PLAN Region 1 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Portland, Oregon Approved: Operations Office, Wildlife Service Date: I PRIMARY AUTHOR The Recovery Plan for Thirteen Plant Taxa from the Northern Channel Islands was prepared by: Tim Thomas U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1 DISCLAIMER Recovery plans delineate reasonable actions which are believed to be required to recover and/or protect listed species. We (the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service) publish recovery plans, sometimes preparing them with the assistance of recovery teams, contractors, State agencies, and others. Objectives of the recovery plan will be attained and any necessary funds made available subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities. Costs indicated for task implementation and/or time for achievement ofrecovery are only estimates and are subject to change. Recovery plans do not necessarily represent the views, official positions, or approval ofany individuals or agencies involved in the plan formulation other than our own. They represent our official position only after they have been signed by the Director, Regional Director, or CalifornialNevada Operations Office Manager as approved. Approved recovery plans are subject to modification as dictated by new findings, changes in species status, and the completion of recovery tasks. Literature citation should read: U.S. -

Plants of Havasu National Wildlife Refuge

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Plants of Havasu National Wildlife Refuge The Havasu NWR plant list was developed by volunteer Baccharis salicifolia P S N John Hohstadt. As of October 2012, 216 plants have been mulefat documented at the refuge. Baccharis brachyphylla P S N Legend shortleaf baccharis *Occurance (O) *Growth Form (GF) *Exotic (E) Bebbia juncea var. aspera P S N A=Annual G=Grass Y=Yes sweetbush P=Perennial F=Forb N=No Calycoseris wrightii A F N B=Biennial S=Shrub T=Tree white tackstem Calycoseris parryi A F N Family yellow tackstem Scientific Name O* GF* E* Chaenactis carphoclinia A F N Common Name pebble pincushion Agavaceae—Lilies Family Chaenactis fremontii A F N Androstephium breviflorum P F N pincushion flower pink funnel lily Conyza canadensis A F N Hesperocallis undulata P F N Canadian horseweed desert lily Chrysothamnus Spp. P S N Aizoaceae—Fig-marigold Family rabbitbrush Sesuvium sessile A F N Encelia frutescens P S N western seapurslane button brittlebrush Encelia farinosa P S N Aizoaceae—Fig-marigold Family brittlebrush Trianthema portulacastrum A F N Dicoria canescens A F N desert horsepurslane desert twinbugs Amaranthaceae—Amaranth Family Antheropeas wallacei A F N Amaranthus retroflexus A F N woolly easterbonnets redroot amaranth Antheropeas lanosum A F N Tidestromia oblongifolia P F N white easterbonnets Arizona honeysweet Ambrosia dumosa P S N burrobush Apiaceae—Carrot Family Ambrosia eriocentra P S N Bowlesia incana P F N woolly fruit bur ragweed hoary bowlesia Geraea canescens A F N Hydrocotyle verticillata P F N hairy desertsunflower whorled marshpennywort Gnaphalium spp. -

The Tribe Cichorieae In

Chapter24 Cichorieae Norbert Kilian, Birgit Gemeinholzer and Hans Walter Lack INTRODUCTION general lines seem suffi ciently clear so far, our knowledge is still insuffi cient regarding a good number of questions at Cichorieae (also known as Lactuceae Cass. (1819) but the generic rank as well as at the evolution of the tribe. name Cichorieae Lam. & DC. (1806) has priority; Reveal 1997) are the fi rst recognized and perhaps taxonomically best studied tribe of Compositae. Their predominantly HISTORICAL OVERVIEW Holarctic distribution made the members comparatively early known to science, and the uniform character com- Tournefort (1694) was the fi rst to recognize and describe bination of milky latex and homogamous capitula with Cichorieae as a taxonomic entity, forming the thirteenth 5-dentate, ligulate fl owers, makes the members easy to class of the plant kingdom and, remarkably, did not in- identify. Consequently, from the time of initial descrip- clude a single plant now considered outside the tribe. tion (Tournefort 1694) until today, there has been no dis- This refl ects the convenient recognition of the tribe on agreement about the overall circumscription of the tribe. the basis of its homogamous ligulate fl owers and latex. He Nevertheless, the tribe in this traditional circumscription called the fl ower “fl os semifl osculosus”, paid particular at- is paraphyletic as most recent molecular phylogenies have tention to the pappus and as a consequence distinguished revealed. Its circumscription therefore is, for the fi rst two groups, the fi rst to comprise plants with a pappus, the time, changed in the present treatment. second those without. -

Malacothrix Squalida (Island Malacothrix)

Malacothrix indecora (Santa Cruz Island malacothrix) and Malacothrix squalida (island malacothrix) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation Malacothrix indecora, A.K. McEachern, United States Geological Survey Malacothrix squalida, S. McCabe, Arboretum at the University of California Santa Cruz U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Ventura Fish and Wildlife Office Ventura, California August 2010 5-YEAR REVIEW Malacothrix indecora (Santa Cruz Island malacothrix) and Malacothrix squalida (island malacothrix) I. GENERAL INFORMATION Purpose of 5-Year Reviews: The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) is required by section 4(c)(2) of the Endangered Species Act (Act) to conduct a status review of each listed species at least once every 5 years. The purpose of a 5-year review is to evaluate whether or not the species’ status has changed since it was listed (or since the most recent 5-year review). Based on the 5-year review, we recommend whether the species should be removed from the list of endangered and threatened species, be changed in status from endangered to threatened, or be changed in status from threatened to endangered. Our original listing of a species as endangered or threatened is based on the existence of threats attributable to one or more of the five threat factors described in section 4(a)(1) of the Act, and we must consider these same five factors in any subsequent consideration of reclassification or delisting of a species. In the 5-year review, we consider the best available scientific and commercial data on the species, and focus on new information available since the species was listed or last reviewed. -

+ Traversing Swanton Road

+ Traversing Swanton Road (revised 02/22/2016) By James A. West Abstract: Situated at the northwest end of Santa Cruz County and occupying circa 30 square miles of sharply contrasted terrain, the Scott Creek Watershed concentrates within its geomorphological boundaries, at least 10-12% of California's flora, both native and introduced. Incorporated within this botanical overview but technically not part of the watershed sensu strictu, are the adjacent environs, ranging from the coastal strand up through the Western Terrace to the ocean draining ridge tops..... with the Arroyo de las Trancas/Last Chance Ridge defining the western/northwestern boundary and the Molino Creek divide, the southern demarcation. Paradoxically, the use/abuse that the watershed has sustained over the past 140+ years, has not necessarily diminished the biodiversity and perhaps parallels the naturally disruptive but biologically energizing processes (fire, flooding, landslides and erosion), which have also been historically documented for the area. With such a comprehensive and diverse assemblage of floristic elements present, this topographically complex but relatively accessible watershed warrants utilization as a living laboratory, offering major taxonomic challenges within the Agrostis, Arctostaphylos, Carex, Castilleja, Clarkia, Juncus, Mimulus, Pinus, Quercus, Sanicula and Trillium genera (to name but a few), plus ample opportunities to study the significant role of landslides (both historical and contemporary) with the corresponding habitat adaptations/modifications and the resulting impact on population dynamics. Of paramount importance, is the distinct possibility of a paradigm being developed from said studies, which underscores the seeming contradiction of human activity and biodiversity within the same environment as not being mutually exclusive and understanding/clarifying the range of choices available in the planning of future land use activities, both within and outside of Swanton.