Weaving a Virtual Web: Practical Approaches to New Information Technologies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix 1: Temporary (Special) Exhibitions, 1912–1983 Peter J.T

Appendix 1: Temporary (Special) Exhibitions, 1912–1983 Peter J.T. Morris and Eduard von Fischer The year given is the year the exhibition opened; it may have continued into the following calendar year. The main source before 1939 is Appendix I of E.E.B. Mackintosh, ‘Special Exhibitions at the Science Museum’ (SMD, Z 108/4), which has been followed even when the exhibitions do not appear in the Sceince Museum Annual Reports, supplemented by the list in Follett, The Rise of the Science Museum, pp. 122–3. Otherwise the exhibitions have been taken from the Annual Reports. 1912 History of Aeronautics 1914 Gyrostatics 1914 Science in Warfare First World War 1919 Aeronautics James Watt Centenary 1923 Typewriters 1924 Geophysical and Surveying Instruments Kelvin Centenary Centenary of the Introduction of Portland Cement 1925 Stockton and Darlington Railway Centenary Centenary of Faraday’s Discovery of Benzine [sic] Wheatstone Apparatus Seismology and Seismographs 1926 Adhesives Board, DSIR Centenary of Matthew Murray Fiftieth Anniversary of the Invention of the Telephone 1927 British Woollen and Worsted Research Association British Non-Ferrous Metals Research Association Solar Eclipse Phenomena Newton Bi-centenary 1928 George III Collection of Scientific Apparatus Cartography of the Empire Modern Surveying and Cartographical Instruments Weighing Photography 317 318 Peter J.T. Morris and Eduard von Fischer 1929 British Cast Iron Research Association Newcomen Bicentenary Historical Apparatus of the Royal Institution Centenary of the Locomotive Trials -

STS Departments, Programs, and Centers Worldwide

STS Departments, Programs, and Centers Worldwide This is an admittedly incomplete list of STS departments, programs, and centers worldwide. If you know of additional academic units that belong on this list, please send the information to Trina Garrison at [email protected]. This document was last updated in April 2015. Other lists are available at http://www.stswiki.org/index.php?title=Worldwide_directory_of_STS_programs http://stsnext20.org/stsworld/sts-programs/ http://hssonline.org/resources/graduate-programs-in-history-of-science-and-related-studies/ Austria • University of Vienna, Department of Social Studies of Science http://sciencestudies.univie.ac.at/en/teaching/master-sts/ Based on high-quality research, our aim is to foster critical reflexive debate concerning the developments of science, technology and society with scientists and students from all disciplines, but also with wider publics. Our research is mainly organized in third party financed projects, often based on interdisciplinary teamwork and aims at comparative analysis. Beyond this we offer our expertise and know-how in particular to practitioners working at the crossroad of science, technology and society. • Institute for Advanced Studies on Science, Technology and Society (IAS-STS) http://www.ifz.tugraz.at/ias/IAS-STS/The-Institute IAS-STS is, broadly speaking, an Institute for the enhancement of Science and Technology Studies. The IAS-STS was found to give around a dozen international researchers each year - for up to nine months - the opportunity to explore the issues published in our annually changing fellowship programme. Within the frame of this fellowship programme the IAS-STS promotes the interdisciplinary investigation of the links and interaction between science, technology and society as well as research on the development and implementation of socially and environmentally sound, sustainable technologies. -

Maine Museums

Maine Policy Review Volume 24 Issue 1 Humanities and Policy 2015 Maine Museums Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mpr Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation "Maine Museums." Maine Policy Review 24.1 (2015) : 60 -63, https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mpr/vol24/iss1/19. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. Public Humanities: MAINE MUSEUMS Maine Museums Aroostook Piscataquis Somerset Penobscot Washington Franklin Hancock Waldo Oxford Kennebec Knox Lincoln Androscoggin Legend Sagadahoc = History = Art Cumberland = Combined = Other Augusta “Combined” museums Brunswick have several types of collec- York tions, e.g. art + history, Portland anthropology + history. This list of museums and historical societies is adapted from one provided by Maine Archives & Museums and is not an exhaustive list of all museums. The map was produced with support from the Spatial Informatics group in the School of Computing and Information Science, University of Maine. MAINE POLICY REVIEW • Vol. 24, No. 1 • 2015 60 Public Humanities: MAINE MUSEUMS Androscoggin Greene Greene Historical Society ................. Portland Portland Museum of Art .................. Lewiston Franco Center . Lewiston Museum L- A ........................... Portland Tate House Museum...................... Livermore Livermore-Livermore Falls Historical Society Pownal Pownal Scenic & Historical Society ......... Livermore Washburn-Norlands Living History Center .. Scarborough Scarborough Historical Society Inc.......... Poland Poland Spring Preservation Society ........ South Portland Turner Turner Museum & Historical Association ... South Portland Historical Society/ Cushings Point Museum . Aroostook Windham Windham Historical Society . Frenchville Frenchville Historical Society .............. Yarmouth Skyline Farm Carriage Museum............ Grand Isle Greater Grand Isle Historical Society . Yarmouth Yarmouth Historical Society ............... Littleton Southern Aroostook Agricultural Museum . -

ASTC List CORRECT As of Dec 09

Association of Science-Technology Centers Discovery Center Science Museum, Fort Collins (970) 221-6738 Iowa Durango Discovery Kids, Durango Discovery Museum, Durango (970) 259-9234 Family Museum, Bettendorf (563) 344-4106 ASTC Travel Passport Program Grout Museum District: Bluedorn Science Imaginarium, Waterloo (319) 234-6357 November 1, 2009 to April 30, 2010 Connecticut Putnam Museum and IMAX Theatre, Davenport (563) 324-1933 Bruce Museum, Greenwich (203) 869-6786 Science Center of Iowa & Blank IMAX Dome Theater, Des Moines (515) 274-6868 The Travel Passport Program entitles visitors to free general admission. It The Children's Museum, West Hartford (860) 231-2830 Science Station, Cedar Rapids (319) 363-4629 does not include free admission to special exhibits, planetarium and larger- Discovery Museum, Inc., Bridgeport (203) 372-3521 screen theater presentations nor does it include museum store discounts DNA EpiCenter, New London (860) 442-0391 Kansas and other benefits associated with museum membership unless stated Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, New Haven (203) 432-8987 Exploration Place, Inc., Wichita (316) 263-3373 otherwise. Each museum has its own admissions policy . Visit Sternberg Museum of Natural History, Hays (785) 628-5516 Delaware University of Kansas Natural History Museum, Lawrence (785) 864-4540 www.astc.org to find out which and how many family members receive free Delaware Museum of Natural History, Wilmington (302) 658-9111 admission. Hagley Museum and Library, Wilmington (302) 658-2400 Kentucky Iron Hill -

Assessing the Economic Impact of Science Centers on Their Local

ISBN 0 9751377-2-7 ISBN 0 9751377-5-5 Electronic version This report may be reproduced in whole or in part, subject to the inclusion of an acknowledgement of the source and no commercial usage or sale. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to: Science Centre Economic Impact Study, Questacon – The National Science and Technology Centre, PO Box 5322, Kingston ACT 2604, Australia. The views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of the institutions that have funded this study or contributed data for it. Contents Chapter 1 Summary and key findings....................................................................................................................1 Chapter 2 Introduction ...........................................................................................................................................5 Chapter 3 Objectives of the project.......................................................................................................................7 Chapter 4 Project stages........................................................................................................................................9 Chapter 5 What is ‘the economic impact of a science center’? .......................................................................11 5.1 Overview .............................................................................................................................................................................11 5.2 Direct economic impact.....................................................................................................................................................12 -

Open PDF 424KB

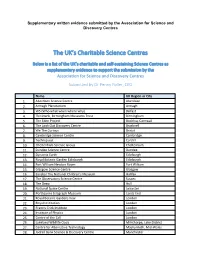

Supplementary written evidence submitted by the Association for Science and Discovery Centres The UK’s Charitable Science Centres Below is a list of the UK’s charitable and self-sustaining Science Centres as supplementary evidence to support the submission by the Association for Science and Discovery Centres Submitted by Dr Penny Fidler, CEO Name UK Region or City 1. Aberdeen Science Centre Aberdeen 2. Armagh Planetarium Armagh 3. W5 (Who what when where why) Belfast 4. Thinktank, Birmingham Museums Trust Birmingham 5. The Eden Project Bodelva, Cornwall 6. The Look Out Discovery Centre Bracknell 7. We The Curious Bristol 8. Cambridge Science Centre Cambridge 9. Techniquest Cardiff 10. Cheltenham Science Group Cheltenham 11. Dundee Science Centre Dundee 12. Dynamic Earth Edinburgh 13. Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh Edinburgh 14. Fort William Newton Room Fort William 15. Glasgow Science Centre Glasgow 16. Eureka! The National Children's Museum Halifax 17. The Observatory Science Centre Sussex 18. The Deep Hull 19. National Space Centre Leicester 20. Porthcurno telegraph Museum Lands End 21. Royal Botanic Gardens Kew London 22. Royal Institution London 23. Francis Crick Institute London 24. Institute of Physics London 25. Centre of the Cell London 26. Lakeland Wildlife Oasis Milnthorpe, Lake District 27. Centre for Alternative Technology Machynlleth, Mid-Wales 28. Jodrell Bank Science & Discovery Centre Manchester 29. International Centre For Life Newcastle 30. Kielder Observatory Northumberland 31. Scottish Seabird Centre North Berwick 32. Oxford University Museum of Natural History Oxford 33. Science Oxford Oxford 34. National Marine Aquarium Plymouth 35. EXplora Science and Discovery Centre Poole 36. MAGNA Rotherham 37. -

Glasgow and Strathclyde Scottish Ancient Egyptian Collections Review East Ayrshire Leisure

Detail of a carved relief from the temple of Bastet at Tell Basta, McLean Museum & Art Gallery, Greenock, Inverclyde Council © Museums Galleries Scotland Ancient Egyptian Collections in Scottish Museums Glasgow and Strathclyde Scottish Ancient Egyptian Collections Review East Ayrshire Leisure Contact Claire Gilmour [email protected] Bruce Morgan [email protected] Location of Collections In storage Primary contact location: The Dick Institute Elmbank Avenue Kilmarnock KA1 3BT Size of collections >45 objects Published Information Online collections: Selection available at www.futuremuseum.co.uk Online exhibition: The Journey Beyond, http://www.futuremuseum.co.uk/collections/features/online-exhibitions/the-journey- beyond.aspx Collection Highlights • Islamic foot rasp in the shape of a crocodile, previously labelled as a ‘lizard coffin’ (c. AD 1800–1900). • Two artworks by David Young Cameron (1865 –1945), a watercolour depicting the temple at Luxor and an etching showing the fort at the Moqattam Hills, Cairo. Collection Overview The collection cared for by East Ayrshire Leisure was initially formed in Kilmarnock as part of the Dick Institute, which opened in 1901 following the provision of funding by Kilmarnock- born industrialist James Dick (1823–1902). Part of the collection was formed in the following years. In 1909 a fire swept through the museum, damaging some objects and destroying others, while many of those that survived became disassociated from their object histories. The museum re-opened in 1911. The collection is built up primarily of material collected by visitors and tourists to Egypt, including amulets and metal figurines, faience shabtis and small Coptic objects. The collection also includes a number of modern shabtis and scarabs. -

List of Organisations to Which the Consultation Paper Has Been Sent

The consultation paper has been sent to the following organisations: Aberdeen Art Gallery Art Loss Register Ashmolean Museum Birmingham City Art Gallery Board of Deputies of British Jews Bowes Museum, County Durham British Council British Library British Museum Christies Commission for Looted Art in Europe Compton Verney Constantine Ltd Dept for Culture, Arts and Leisure Northern Ireland Djanogly Art Gallery, Nottingham Dulwich Picture Gallery City Arts Centre, Edinburgh English Heritage Estorick Collection Farrers Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge Gilbert Collection Burrell Collection, Glasgow Kelvingrove Museum, Glasgow Harewood House Trust, Leeds Harris Gallery, Preston HM Revenue and Customs International Council Of Museums UK Imperial War Museum Jewish Museum Abbot Hall Gallery, Kendal Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle Upon Tyne Leeds Art Gallery Manchester Art Gallery Martinspeed Momart Museum Copyright Group Museum Documentation Association Museums Association Museums Libraries and Archives Council National Gallery National Library of Scotland National Maritime Museum National Museums and Galleries of Wales National Museums of Northern Ireland National Museums of Scotland National Portrait Gallery Natural History Museum National Museums Directors’ Conference Northern Ireland Museums Council Norwich Castle Art Gallery Reviewing Committee Royal Academy Royal Armouries Sainsbury Centre, Norwich Science Museum Science Museum Scottish Council of Jewish Communities Scottish Executive Sothebys Southampton Art Gallery Swansea Museum Swift Find Tate The Ben Uri Gallery The British Council The Courtauld Institute The Lowry Centre Salford The Metropolitan Art and Antiquities Unit The National Trust The Society of Antiquaries of London The Wallace Collection UK Registrars Victoria & Albert Museum Welsh Assembly Whitechapel Art Gallery Withers . -

2013-14 Annual Report EN Copy.Pdf

2013–2014 ANNUAL REPORT An agency of the Government of Ontario Our Vision We will be the leader among science centres in providing inspirational, educational and entertaining science experiences. Our Purpose We inspire people of all ages to be engaged with the science in the world around them. Our Mandate • Offer a program of science learning across Northern Ontario • Operate a science centre • Operate a mining technology and earth sciences centre • Sell consulting services, exhibits and media productions to support the centre’s development Our Professional Values We Are…Accountable, Innovative Leaders We Have…Respect, Integrity and Teamwork Table of Contents 4 Message from the Chair and Chief Executive Officer 7 Fast Facts 8 Meet Our Bluecoats 10 People We’ve Inspired 12 Future Scientists 14 Our 5-year Strategic Priorities 17 Strategic Priority 1: Great and Relevant Science Experiences 25 Strategic Priority 2: A Customer-Focused Culture of Operational Excellence 37 Strategic Priority 3: Long Term Financial Stability 48 Science North Funders, Donors and Sponsors 51 Science North Board of Trustees and Committee Members 52 Science North Staff 53 Appendix A: Audited Financial Statements 3 MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR AND CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER 2013-14 marked the first year of Science North’s new exhibit goes on tour to other science centres and museums as five-year Strategic Plan. Over the past 12 months we’ve made Science North’s 10th travelling exhibition. Science North’s newest substantial progress in meeting our strategic priorities of great large format film Wonders of the Arctic had its world premiere at and relevant science experiences, a customer focused culture Science North on March 6th and is an excellent complement to of operational excellence and long term financial stability. -

2009-2010 Contact List by County

2009-2010 CONTACT LIST BY COUNTY Adair Kentucky Homeplace Adair County Adult Education Ballard WKCA Radio Adair County High School The Advance Yeoman WIVY Radio Adair County Middle School Ballard County Adult Education Adair County Public Library Ballard County Cooperative Bell Lindsey Wilson College Extension Service Bell Central School Center WAIN Radio Ballard County Middle School Bell County Adult Education WAVE Radio Ballard Memorial High School Bell County High School WHVE Radio Ballard Weekly Middlesboro High School Daymar College Middlesboro Middle School Allen Sylvan Learning Center Page School Center Allen County Board of Education WBCE Radio Pineville High School Allen County Cooperative WBEL Radio Southeast Kentucky Community Extension Service WCBL Radio and Technical College, Allen County-Scottsville High West Kentucky Community and Cumberland Campus School Technical College, Kevil Allen County-Scottsville Youth Campus Boone Services Center WGCF Radio Boone County Adult Education Allen County Technical Center Boone County Board of Education Department for Community Based Barren Boone County Cooperative Services Barren County High School Extension Service - Family Support Barren County Middle School Boone County High School - Protection and Permanency Caverna Elementary School Boone County Public Library James E. Bazzell Middle School Caverna Schools Readifest - Florence Branch Lindsey Wilson College, Columbia Avenue Church of - Lentz Branch Scottsville Campus Christ - Main Branch White Plains Learning Center Glasgow Area Career Center Camp Ernst Middle School Glasgow High School Citi Financial Group Anderson Glasgow Middle School Conner High School Anderson County Adult Education South Green Elementary School Conner Middle School Anderson County Back to School Western Kentucky University, Gray Middle School Block Party Glasgow Campus Heritage Academy Anderson County Board of - Educational Opportunity Larry A. -

STEAM Websites & Resources

STEAM websites & resources Science, Engineering, Technology, Maths & Design information & resources Sources of ideas for STEM activities and demonstrations Activities for STEM Clubs – nine KS3 level STEM club activities from the Institute of Physics All About STEM – links to STEM activities, events, programmes and resources All things STEAM – US librarian’s STEAM club projects & experiments Arkive Education – endangered species education videos & resources from wildlife charity Wildscreen CREST Awards – STEM challenge & award scheme and resources CREST Star – encouraging primary students to solve STEM problems through practical investigation Dendrite – hub of the Bloodhound SSC educational programme Fab Foundation – the parent organisation of the FabLab maker movement IET Faraday – classroom activities, online games, videos, quizzes, supporting material and challenges Illusioneering – science based easy to perform ‘magic’ tricks for home or classroom Lunar Exploration – interactive history & technology of the moon missions, from the ESA MakerSpaces – the parent organisation of the MakerSpace maker movement Planet Science – articles, ideas & activities to inspire students about science Physics Classroom – interactive physics demos, tutorials, simulations and more Quirkology – STEAM based magic, illusions and intriguing demonstrations Robot Orchestra – creating robot musicians and instruments from waste and recycled materials See Science – STEM activities and competitions listings from the Welsh STEM Ambassador hub Science Buddies – US -

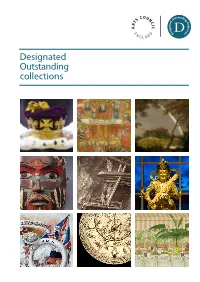

Designated Outstanding Collections Contents

Designated Outstanding collections Contents 3 Introduction 4 East Midlands 6 East 10 London 20 North East 22 North West 27 South East 31 South West 37 West Midlands 43 Yorkshire Introduction The Designation Scheme is a mark of distinction, identifying and celebrating pre-eminent collections of national and international importance in non-national institutions. The Scheme was established in 1997 by the Museums and Galleries Commission (MGC) in collaboration with the then Department of National Heritage as a result of a commitment in the 1996 Government policy document, Treasures in Trust. In 2005 Designation was extended to include libraries and archives. The Scheme is now administered by Arts Council England, aiming to raise standards and promote best practice across the sector. There are currently 140 Designated collections held in organisations across the whole of England. The following descriptions of the outstanding collections recognised by the Designation Scheme demonstrate the immense richness and variety of the collections held in England’s museums, libraries and archives. These world class collections are a lasting source of inspiration and enjoyment for generations of users and Designation exists to promote and increase access to them for all. Cover images 1. Crown. Photo: 4. Copper Mask. Photo: 7. Tyne & 1 2 3 Kensington Royal Palace. University of Cambridge Wear Archives. Photo: Peter 2. Page from the Cologne Museum of Archaeology Skelton. 4 5 6 Chronicle, 1499. Photo: and Anthropology. 8. Islamic Astrolabe, pre Chetham’s Library. 5. Tin miners. Photo: 1636, Museum of the 3. Landscape with a Cornwall Record Office. History of Science, Oxford 7 8 9 Rainbow, by Joseph Wright 6.