The Guru in America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BOHR Vs. EINSTEIN

SACH KHAND THE JOURNAL OF RADHASOAMI STUDIES | Issue Four | MSAC Philosophy Group | Mt. San Antonio College | Walnut, California 91789 | USA | The Genealogical Connection: Kirpal Singh & Paul Twitchell That religions often evolve out of other past religions is a well-known phenomenon: witness Christianity's emergence from Judaism. What is not so well known, however, is how certain religions try to genealogically dissociate themselves from their historical roots. Eckankar is a classic case in point. Founded in 1965 by Paul Twitchell, one-time disciple of Swami Premananda, Kirpal Singh, and L. Ron Hubbard, Eckankar owes much of its theology to Radhasoami. Indeed, as Lane, Melton, and others have pointed out, most of Paul Twitchell's writings are derived from two Radhasoami publications, With a Great Master in India and The Path of the Masters (both authored by Julian P. Johnson in the 1930s). Certainly, it is not surprising that religious doctrines can at times appear to be similar, but what is surprising is when a religion which has borrowed much of its history, doctrine, and terminology from another tries to consciously deny its putative association. The story of Paul Twitchell's association with Kirpal Singh, and, in turn, the influence of Radhasoami on Eckankar, is well documented. In 1955 Paul Twitchell received initiation from Kirpal Singh in Washington, D.C. Twitchell, who, according to his first wife Camille Ballowe Taylor, was a "seeker of religion," met Kirpal Singh after a five year stay at Swami Premananda's Church of Absolute Monism. Twitchell kept up a ten year correspondence with Kirpal Singh in India, addressing his numerous letters to his guru as "My Dear Master," and so on. -

The Five Dacoits the Five Perversions of Mind from the Path of the Masters by Julian Johnson Sant Kirpal Singh Ji, Hazur Baba Sawan Singh Ji, and Others

The Five Dacoits The Five Perversions of Mind From The Path of the Masters by Julian Johnson Sant Kirpal Singh Ji, Hazur Baba Sawan Singh Ji, and others We are constantly beset by five foes - passion, anger, greed, worldly attachments, and vanity. All these must be mastered, brought under control. You can never do that entirely until you have the aid of the Guru and are in harmonic relations with the Sound Current. But you can begin now, and every effort will be a step on the way. (Baba Sawan Singh, Spiritual Gems, 339) Swami Ji has said that we should not hesitate to go all out to still the mind. We do not fully grasp that the mind takes everyone to his doom. It is like a thousand-faced snake, which is constantly with each being; it has a thousand different ways of destroying the person. The rich with riches, the poor with poverty, the orator with his fine speeches – it takes the weakness in each and plays upon it to destroy him. (Sant Kirpal Singh Ji) ruhanisatsangusa.org/serpent.htm Contents Page: 1. The Five Perversions of Mind, from The Path of the Masters, by Julian Johnson 2. Biography of Julian Johnson, from Wikipedia 3. Lust– Julian Johnson 5. The Case for Chastity, Parts 1 & 2 from Sat Sandesh 6. Sant Kirpal Singh Ji on Chastity 7. Hazur Baba Sawan Singh 8. Anger– Julian Johnson 10. Anger Quotes 11. Sant Kirpal Singh on Anger 12. Baba Sawan Singh, Jack Kornfield 13. Greed– Julian Johnson 14. Greed Quotes 15. -

Spiritual Link June 2012 3 a Matter of Trust

June 2012 Science of the Soul Research Centre contents 2 Yours Affectionately 4 A Matter of Trust 6 A Story of Love 11 Something to Think About 15 Did You Know? 16 Stormy Weather 20 Serving Endlessly 21 It Matters to Him 23 The Attitude of a Disciple 24 Bliss 26 The Master Answers 29 To See Him Again 32 Repartee of the Wise 33 In Abundance 37 Memorable Quotes 38 Paralysis of Analysis 40 Spiritualisticks 41 Empty Your Cup 42 All We Have Is This Moment 47 Heart to Heart 48 Book Review Spiritual Link Science of the Soul Research Centre Guru Ravi Dass Marg, Pusa Road, New Delhi-110005, India Copyright © 2012 Science of the Soul Research Centre® Articles and poems that appear without sources have been written by the contributors to this magazine. VOLUME 8 • ISSUE SIX • JUNE 2012 June 2012 1 Yours Affectionately A Letter from Maharaj Charan Singh The very reason we are placed on this earth is to enable us to realize God within ourselves. Whatever circumstances we find ourselves in are due to previous karmas, and so long as we try to act in accordance with his will, whatever the results may be – whether pleasant or unpleasant – it helps us in our spiritual progress. To go back to our Father’s house is the main purpose of this life. All other things we do simply to maintain ourselves in this world. But while doing so, we should not forget the Father who has given us all these things. You are very lucky to have been given the way to realize the Master within yourself, so you should always devote as much time to simran and bhajan as possible, as that is the only way by which we can be cleansed so that we may be liberated. -

Stone Et La Tradition

LA TRADITION ET L'ART DE GUÉRIR DANS LA THÉRAPIE PAR POLARITÉ Par Benoît-Luc Simard, Ph. D. Avant de pouvoir vous parler de la tradition en général et de celle de la Chine en particulier, il faut que je situe les influences majeures que Randolph Stone a reçues tout au long de sa vie. Je commencerai donc par une brève biographie qui nous amènera à considérer son adhésion aux Radhasoami comme un événement majeur dans la vie de Stone et ensuite seulement je vous parlerai de la tradition Biblique, Grecque et Chinoise. Et pour bien attirer votre attention, je vous cite ce que dit Randoph Stone à propos de l'acupuncture : « What the needles can do, the hands can do better ». Nous verrons à la toute fin pour quelles raisons il parle ainsi de l'acupuncture. Je dois dire, en premier lieu, que cette thérapie n'est pas très présente au Québec alors qu'il existe plusieurs associations de membres aux États-unis (environ 1000 membres), au Royaume-Uni (35), en Allemagne (70), Autriche, Suisse (300), au Japon, Espagne (200 membres) et, plus près de nous, en Ontario (60 membres). Voici tout d'abord quelques notes sur le fondateur de cette thérapie. Randolph Stone est né sous le nom de Rudolph Bauch. Il a treize ans lorsqu'en 1903 il quitte l'Autriche et immigre aux États-Unis avec sa famille. Peu de temps après son arrivée, il travaillera comme manœuvre, il étudiera pour devenir pasteur au Concordia Lutheran College du Minnesota, mais ne continuera pas dans cette voie pour cause de maladie et, enfin, apprendra le métier de machiniste industriel. -

Informatlûn to USERS

INFORMATlûN TO USERS This manuscript has been reptoduced from the rnicmfïlrn master- UMI films the text directly from the onginal or copy wbmitted. Thus. methesis and dissertation copies are in typemiter faceI Mile others may be fram any type of cornputer printer- The quality of tkk reproduction h âepenôent upon the qrvlity of the copy submittad. Brd<en or indistinct Wt. cobnd or poor qua- illurtrsbks and photographs. print bkedtf~mugh,substandaid margins. and impropor ali@ment can adversely aned repnrduction- In the unlikely event ümt üie author dicl not wnd UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages. these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized oopyfight material had bo be mmoved, a note will indicate the deieüon. Ovenize matarials (e.g., maps. drawings. char&) are reprocklced by sectiming the original, begiming at the upper Iefthand and oaibnuing fiom left to right in equal secüons with small overlaQsrlaQs Photographs induded in the original manusaipt have bwn reprodd xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x gm Mock and white photographie prints are available for any photogmphs or illustrationS ~ppearingin mis cmfor an additional charge. Contact UMI diredly to der. Bell & Howell Information and Leaming 300 North ïeeb Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 USA Benoît-Luc Siniard LA TEIÉRAPIE PAR POLARITÉ : RECHERCHE EXPLORATOIRE SUR LES FONDEMENTS ET LA COAÉRENCE D'UNE MÉDECINE DOUCE Mémoire présenté à la Faculté des études supérieures de l'Université Lavai pour l'obtention du grade de mltre es ans (M.A.) Progamme de maîtrise en sciences des reliçions FACULTE DE THÉOLOGIE ET DE SCIENCES RELIGIEUSES UNIVERSITÉ LAVAL JANVIER 1999 a Bcnoit-Luc Simard, 1999 National Library Bibliothèque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibiiographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. -

Spiritual Elixir.Pdf

BABA SAWAN SINGH JI MAHARAJ (1858-1948) Dedicated to the Almighty God working through all Masters who have come and Baba Sawan Singh Ji Maharaj at whose lotus feet the author imbibed the sweet elixir of Holy NAAM- the WORD. KIRPAL SINGH First Edition - 1967 Second Printing - 1978 Second Edition - 1988 ISBN 0-942735-02-1 Reprinted By RUHANI SATSANG@BOOKS, 2618 Skywood Place, Anaheim, California, 92804 U.S.A. FOREWORD It is an honor to have been asked to say something concerning the outstanding competence of the author of SPIRITUAL ELIXIR. The content of the book itself bespeaks his personal simplicity in his efforts to be of utmost service to mankind. Having served for four consecutive terms as the President of the WORLD FELLOWSHIP OF RELIGIONS, Kirpal Singh was able to meet at a personal level most of the religious heads in India and many religious delegates from abroad who attended the large WFR Confer- ences held in India. During his extensive tours of the West in 1955, 1963-64, and in 1972, he was able to meet many religious heads in Europe and America, as well as the political leaders of many Western countries. He spoke English, as well as the major languages of his native India, and this enabled him to converse easily with people of diverse cultural backgrounds. Until his retirement from government service, he served in a civilian capacity in the Division of Mili- tary Accounts of the Government of India. On his three tours of the West, as well as during his extensive travels in his native India, he welcomed his many opportunities to interact with the man on the street or road-side. -

A Study of the Movement of Spiritual Inner Awareness This Page Intentionally Left Blank a Study of the Movement of Spiritual Inner Awareness

A Study of the Movement of Spiritual Inner Awareness This page intentionally left blank A Study of the Movement of Spiritual Inner Awareness Religious Innovation and Cultural Change Diana G. Tumminia and James R. Lewis A STUDY OF THE MOVEMENT OF SPIRITUAL INNER AWARENESS Copyright © Diana G. Tumminia and James R. Lewis, 2013. Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2013 978-1-137-37418-9 All rights reserved. First published in 2013 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN® in the United States—a division of St. Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Where this book is distributed in the UK, Europe and the rest of the world, this is by Palgrave Macmillan, a division of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries. ISBN 978-1-349-47687-9 ISBN 978-1-137-37419-6 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/9781137374196 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress. A catalogue record of the book is available from the British Library. Design by Newgen Knowledge Works (P) Ltd., Chennai, India. First edition: November 2013 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents List of Figures and Tables vii Introduction ix Chronology xxxiii 1 What Is MSIA? 1 2 Entrance into the Field 23 3 Beginnings 47 4 Prana 65 -

The Path of the Masters

THE PATH OF THE MASTERS The Science of Surat Shabd Yoga SANTON KI SHIKSHA A comprehensive statement of the Teachings of the Great Masters or Spiritual Luminaries of the East. Also an outline of their scientific system of exercises by means of which they attain the highest degree of spiritual development. Yoga of the Audible Life Stream By JULIAN JOHNSON, M.A., B.D., M.D. RADHA SOAMI SATSANG BEAS after living almost seven years with one of the Greatest of the Masters RADHA SOAMI SATSANG BEAS (PUNJAB) INDIA THE AUTHOR A typical Kentuckyan, a distinguished artist, a devout theologian, an ardent flier, an outstanding surgeon and above all a keen seeker after truth, Dr. Julian Johnson, sacrificing his all at a time when he was at the height of his worldly fame, came to answer the call of the East for the second time. The first time was when he voyaged to India to preach the true gospel of Lord Jesus Christ in his inimitable way. He came to enlighten her but eventually had to receive enlighten- ment from her. Caesar came, saw and conquered; the author came, saw and was conquered. It was a day of destiny for him when he came the second time. He was picked up, as it were, from a remote corner and guided to the feet of the Master. Once there, he never left. He assiduously carried out the spiritual discipline taught by one of the greatest living Masters and was soon rewarded. He had the vision of the Reality beyond all forms and ceremonies. -

Baba Sawan Singh His LIFE and His TEACHING

BABA SAWAN SINGH HIS LIFE AND HIS TEACHING BE GOOD – DO GOOD – BE ONE Second Edition: 2021 Published by: UNITY OF MAN – Sant Kirpal Singh Steinklüftstraße 34 A-5340 St. Gilgen – Austria / Europe BABA SAWAN SINGH HIS LIFE AND HIS TEACHING his brief biographical study of Ha- T zur Maharaj Baba Sawan Singh is a combination of several different writings of Sant Kirpal Singh. The basic narrative framework is „A Brief Life Sketch of Baba Sawan Singh Ji Maharaj“, Sant Kirpal Sin- gh’s first bublished writing in English, is- sued by Him in 1949, the year after Baba Sawan Singh’s death. With this „Scenes from a Great Life“, a talk given by Sant Kirpal Singh on one anniversary of Ha- zur’s birth. Brief sections from two other talks in which Sant Kirpal Singh referred to His Master are also included. 2 Baba Sawan Singh His life and His teachingThe Life and Teachings of Baba Sawan Singh Ji 3 The Life and Teachings of Baba Sawan Singh Ji Zuban pe bare-Khudaya ye kis ka num aya Ke mere nutq ne base meri zuban ke liye. By the Grace of God whose name did I mention the faculty of speech has begun to kiss my tongue Who is not acquainted with the name of that Messiah of the modern age? – that living personification of morality, the fountain-head of spirituality, who in the dark abyss of this material world helped many a helpless wanderer to the path of Truth and lighted their dark path. Just a little while ago we ourselves were witnessing the wonderful miracles and the instructive eye-opening incidents which are usually associated with the names of the past Saints and were the actual recipients of the great benefits from that Godman who lived and moved amongst us and showed us the path leading to Reality. -

CONFESSIONS of a God Seeker

CONFESSIONS of a God Seeker A JOURNEY TO HIGHER CONSCIOUSNESS Ford Johnson Published by “ONE” Publishing, Inc. 8720 Georgia Avenue Suite 206 Silver Spring, MD 20910 www.onepublishinginc.com Copyright © 2003 by “ONE” Publishing, Inc. “ONE” Publishing is a registered trademark of “ONE” Publishing, Inc. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copy- right Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Publisher. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the “ONE” Publishing, Inc., 8720 Georgia Avenue, Suite 206, Silver Spring, MD 20910, phone (301) 562-2858, fax (301) 562-9377. “ONE” Publishing books and products are available through most bookstores and on-line through Amazon.com and Barnes&Nobles.com. To contact “ONE” Publishing directly, call (301) 562-2858, fax to (301) 562-9377, or visit our website at www.onepublishing- inc.com. Substantial discounts on bulk quantities of “ONE” Publishing books are available to cor- porations, professional associations, and other organizations. For details and discount information, contact the sales department at “ONE” Publishing. Typeset by Adam Sharif of “ONE” Publishing, Inc., Silver Spring, MD Principal editor: Brian Downing, Ph.D. Design concept: Ford Johnson Original art: Michael Omoighe Graphic art adaption and design: April Gratrix Printed and bound in the USA by Edward Brothers, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 “ONE” Publishing, Inc. -

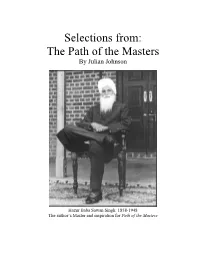

The Path of the Masters by Julian Johnson

Selections from: The Path of the Masters By Julian Johnson Hazur Baba Sawan Singh: 1858-1948 The author’s Master and inspiration for Path of the Masters Preface Julian Johnson (1873-1939) was an American surgeon and author of several books on Eastern spirituality. A native Kentuckian, he left his medical practice in California and traveled to Beas, India, in order to serve his guru, Baba Sawan Singh. From 1933 to 1939, Johnson lived with his guru and devoted much of his time to writing about his Master and his experiences on the path. Johnson grew up in a staunch Christian family, became a Baptist minister at age 17, graduated with a Bachelor of Divinity, and received an appointment as a missionary to India at age 22. Johnson claimed that experiences during his three-year stay in India rendered him surprised by the deep understanding possessed by Indians he had sought to convert, and urged him towards further spiritual study. Back in the USA, he earned a master’s degree in theology, resigned his 17-year Baptist ministership, and earned an M.D. from the State University of Iowa. He served as an assistant surgeon in the United States Navy during World War 1, and later went into private practice. He also owned and flew his own airplanes. Over the years, he took to studies of various religious and philosophical teachings. His spiritual explorations culminated when he visited an old friend who was a disciple of Baba Sawan Singh. Convinced that he had found his path, Johnson requested initiation which was arranged for by Dr. -

Baba Jaimal Singh

UN GRANDE SANTO BABA JAIMAL SINGH La sua Vita e i suoi Insegnamenti KIRPAL SINGH Per informazioni: Unity of Man Italy [email protected] www.unityofman.it Pubblicato e Stampato da: Unity of Man, Verein zur Verbesserung der menschlichen Steinklüftstrasse 34 A-5340 St. Gilgen, Austria www.unity-of-man.org Prima edizione 2015 UN GRANDE SANTO BABA JAIMAL SINGH La sua Vita e i suoi Insegnamenti KIRPAL SINGH Questa musica si riversa da un piano trascendente interiore ed è catturata da un soldato Santo. Canto 9, Sar Bachan Sant Kirpal Singh Ji (1894-1974) Dedicato a Dio Onnipotente che ha operato attraverso tutti i Maestri che sono venuti ed a Baba Sawan Singh Maharaj ai cui piedi di loto l’autore ha assorbito il dolce elisir del Santo Naam – il Verbo. SULL’AUTORE Nella storia umana troviamo solo poche indicazioni di vite che si differenziano dalla maggioranza. L’ideale e la eventualità di un Dio-uomo (colui che è divenuto uno con Dio ed è ‘perfetto come il Padre Suo nei cieli’) si trova in tutte le tradizioni religiose; e molte religioni derivano dalla vita e dall’insegnamento di uno o più di queste eccezionali personalità, il cui impegno in vita consiste nel dimostrarci che anche noi abbiamo la capacità di diventare come loro. Ma mai fu intenzione di quei grandi insegnanti di creare un religione. Essi ebbero una vivida conoscenza della vera natura dell’uomo, il cui scopo è ritornare alla sua sorgente – Dio -, e dal loro insegnamento ogni individuo, anche il più emarginato, può riguadagnare i sui propri valori e dignità.