The Twentieth Century Invention of Ancient Mountains: the Archaeology of Highland Aspromonte

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Studio Di Impatto Ambientale

Studio di Impatto Ambientale richiedente: Comune di Bagaladi P. IVA 00283390805 domicilio o sede legale: Via G. Matteotti, n° 4, 89060 Bagaladi (RC) I tecnici incaricati Dott. Arch. Dattola Antonino Dott. Agr. Denisi Domenico 1 Progetto di miglioramento fondiario d’imboschimento e creazione di aree boscate di superfici non-agricole. Bando PSR 2014 – 2020 - Misura 8, INTERVENTO 8.1.1 Imboschimento e creazione di aree boscate P.S.R. della Regione Calabria 2014 / 2020 MISURA 8 Investimenti nello sviluppo delle aree forestali e nel miglioramento della redditività delle foreste DITTA: COMUNE DI BAGALADI COMUNE DI: BAGALADI LOCALITA’: Piani di Lopa e Monte Embrisi e Monte Torrione PROGETTO: Progetto di miglioramento fondiario d’imboschimento e creazione di aree boscate di superfici non agricole. 2 1 INTRODUZIONE ................................................................................................................................................................... 6 1.1. OBIETTIVI E MOTIVAZIONI ALLA BASE DELL’ISTANZA AVANZATA .................................................................................. 7 1.2. PRINCIPI GENERALI PER LE PROCEDURE DI V.I.A. ........................................................................................................... 7 1.3. IMPOSTAZIONE DELLO STUDIO DI IMPATTO AMBIENTALE ............................................................................................ 11 1.4. NORMATIVA DI RIFERIMENTO IN MATERIA AMBIENTALE ............................................................................................. -

Hellenistic Mortar and Plaster from Contrada Mella Near Oppido Mamertina (Calabria, Italy) Cristina Corti, Laura Rampazzi, Paolo Visonà

Hellenistic Mortar and Plaster from Contrada Mella near Oppido Mamertina (Calabria, Italy) Cristina Corti, Laura Rampazzi, Paolo Visonà To cite this version: Cristina Corti, Laura Rampazzi, Paolo Visonà. Hellenistic Mortar and Plaster from Contrada Mella near Oppido Mamertina (Calabria, Italy). International Journal of Conservation Science, Alexandru Ioan Cuza University Publishing House, 2016, 7, pp.57 - 70. hal-01704228 HAL Id: hal-01704228 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01704228 Submitted on 14 Feb 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CONSERVATION SCIENCE ISSN: 2067-533X Volume 7, Issue 1, January-March 2016: 57-70 www.ijcs.uaic.ro HELLENISTIC MORTAR AND PLASTER FROM CONTRADA MELLA NEAR OPPIDO MAMERTINA (CALABRIA, ITALY) Cristina CORTI1*, Laura RAMPAZZI1, Paolo VISONÀ2 1 Dipartimento di Scienza e Alta Tecnologia, Università degli Studi dell’Insubria, via Valleggio 11, 22100 Como, Italy 2 School of Art and Visual Studies, 236 Bolivar Street, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY 40506 USA Abstract Recent archaeological investigations conducted at contrada Mella, an alluvial terrace near Oppido Mamertina, in southwestern Calabria, have uncovered the remains of a town that was settled by the Tauriani, an Italic people, between the third and the first centuries BC. -

Mare E Monti Dell'aspromonte!

Trekking nel Parco Nazionale dell’Aspromonte Mare e Monti dell’Aspromonte! Tra il mare e i monti per vivere una meravigliosa esperienza naturalistica, culturale ed umana nel sud più profondo dell’ultimo lembo di terra ancorato allo Stivale, uno degli angoli più intatti e meno “esplorati” della Calabria ovvero il Parco Nazionale dell’Aspromonte. Un luogo davvero magico, inaspettato e capace di stupire sotto molti profili. Qui la natura è straordinaria e singolare, caratterizzata dal contrasto tra la montagna con i suoi rilievi che arrivano quasi a 2000 metri e il mare che la circonda quasi come se fosse un’isola. Il programma offre la possibilità di immergersi in questo territorio tra le sue fiumare fosforescenti nelle notti di luna piena, i suggestivi paesi fantasma ed un’isola “grecanica” che parla la lingua di Omero e che conserva usi e tradizioni millenari, tramandati di casa in casa, di focolare in focolare, senza trascurare i tanti bagni nelle limpide acque del Mare Jonio. “pis trechi glìgora de thorì tìpote” (chi va veloce non vede nulla) Durata del Trekking: 8 giorni/7 notti. Numero partecipanti: minimo 06 Viaggio: arrivo/partenza a/da Reggio Calabria Soggiorno: case dell’Ospitalità Diffusa a Bova, azienda Agrituristica ad Amendolea, casette al mare. Tipologia E: non è richiesta una preparazione escursionistica da esperti. Programma 1°giorno 18/06: Benvenuti nell’ Aspromonte Greco e nella terra del Bergamotto! Appuntamento con la guida alle ore 13 alla stazione FS Centrale di Reggio Calabria. Visita al Museo Nazionale della Magna Grecia ( Ospitante i famosi Bronzi di Riace ). Possibilità di passeggiata sul Lungomare di Reggio Calabria: il chilometro più bello d’Italia (D’Annunzio). -

Lista Generale Degli Aventi Diritto Al Voto.Xlsx

ELEZIONI DEL CONSIGLIO METROPOLITANO DI REGGIO CALABRIA DEL 7 AGOSTO 2016 Lista generale degli aventi diritto al voto Fascia Nr. Comune Cognome Nome luogo di nascita Carica A 1 AGNANA CALABRA FURFARO Caterina Locri SINDACO A 2 AGNANA CALABRA CATALANO Domenico Agnana Calabra CONSIGLIERE A 3 AGNANA CALABRA CUSATO Natale Locri CONSIGLIERE A 4 AGNANA CALABRA FILIPPONE Claudio Locri CONSIGLIERE A 5 AGNANA CALABRA LAROSA Antonio Cinquefrondi CONSIGLIERE A 6 AGNANA CALABRA LUPIS Giuseppe Canolo CONSIGLIERE A 7 AGNANA CALABRA MOIO Antonio Locri CONSIGLIERE A 8 AGNANA CALABRA PISCIONERI Paolo Cinquefrondi CONSIGLIERE A 9 AGNANA CALABRA SANSALONE Emanuele Vittorio Locri CONSIGLIERE A 10 AGNANA CALABRA SITA' Alfredo Agnana Calabra CONSIGLIERE A 11 AGNANA CALABRA SITA' Francesca Siderno CONSIGLIERE A 12 ANOIA DEMARZO Alessandro Anoia SINDACO A 13 ANOIA AUDDINO Salvatore Forbach (Francia) CONSIGLIERE A 14 ANOIA BITONTI Vincenzo Taurianova CONSIGLIERE A 15 ANOIA CERUSO Daniele Polistena CONSIGLIERE A 16 ANOIA CONDO' Anna Reggio Calabria CONSIGLIERE A 17 ANOIA MACRI' Francesco Anoia CONSIGLIERE A 18 ANOIA MARAFIOTI Giuseppe Anoia CONSIGLIERE A 19 ANOIA MEGNA Federico Polistena CONSIGLIERE A 20 ANOIA MIRENDA Luca Polistena CONSIGLIERE A 21 ANOIA SARLETI Domenico Anoia CONSIGLIERE A 22 ANOIA SORRENTI Mariantonella Messina CONSIGLIERE A 23 ANTONIMINA CONDELLI Antonio Antonimina SINDACO A 24 ANTONIMINA MAIO Francesco Locri CONSIGLIERE A 25 ANTONIMINA MURDACA Francesco Locri CONSIGLIERE A 26 ANTONIMINA PELLE Luciano Antonimina CONSIGLIERE A 27 ANTONIMINA -

Elenco Strade Percorribili RC

Coordinate Inizio Coordinate Fine legenda: 0 = Circolazione vietata al transito Trasporti eccezionali per l'intero tratto Macch. Trasp. Trasp. Pre25mx1 Pre25mx1 Pre35mx1 N DENOMINAZIONE KM LatitudineLongitudineLatitudineLongitudine 33t 40t 56t 75t 100t 6m 7m Trasp pali trasp carri Agric. Coils MO72t 08t 08t 08t Inn. SS 18 (Gioia Tauro) – Inn. SP 1 44,77 38,236700 16,258938 38,358111 16,024371 SS 106 (Locri) Inn. SP 2 (S. Cristina) – Inn. SP SP 1 Dir 16,42 38,263987 15,993913 38,357978 16,023907 1 (Taurianova) Inn. SS 18 (Pellegrina di SP 2 Bagnara) – Inn. SS 106 94,107 38,151821 16,170050 (Bovalino M.na) Bivio Cosoleto (Inn. SP 2) – SP 2 Bis Madonna dei Campi (Inn. SP 1 15,462 Dir) Inn. SP 2 (Natile Nuovo) – Inn. SP 2 Dir 10,272 SS 106 (Bovalino Marina) Inn. SP 1 (Taurianova) – SP 4 Confine prov.le (Dinami) con 39,871 Circonvallazione di Polistena Inn. SS 18 (Rosarno) – Inn. SS SP 5 53,171 106 (M.na Gioiosa Jonica) Inn. SS 18 (Villa S. Giovanni) – SP 6 27,51 Inn. SP 3 (Bivio per Gambarie) Inn. SS 18 (Gallico Marina) – SP 7 15,432 Inn. SP 3 (Gambarie) Inn. SP 5 (S.Antonio) – Confine SP 008 21,663 provinciale (Passo Croceferrata) Inn. SS 106 (Monasterace SP 9 38,916 Marina) - Confine provinciale Inn. SP 9 (B. Mangiatorella) – SP 9 Dir 3,951 Ferdinandea Terreti – Bivio Ortì - Bivio S. SP 10 16,584 Angelo - Lestì Bivio S. Angelo - Cerasi - SP 11 6,61 Podargoni – Inn. SP 7 Gallico - Villa S. Giuseppe – SP 12 3,761 Villamesa Inn. -

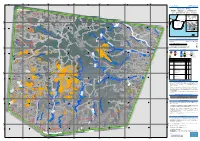

200 Dpi Resolution

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 562500 570000 577500 ! ! 585000 592500 600000 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! 15°40'0"E 15°44'0"E 15°48'0"E ! 15°52'0"E ! 15°56'0"E 16°0'0"E 16°4'0"E 16°8'0"E !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! GLIDE number: N/A Activation ID: EMSR534 ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! Int. Charter Act. ID: N/A Product N.: 01SANLUCA, v1 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! -

The Golden Eagle Aquila Chrysaetos in the Aspromonte National Park: First Surveys on Its Status and Ecology

Avocetta 41: 81-84 (2017) The Golden Eagle Aquila chrysaetos in the Aspromonte National Park: first surveys on its status and ecology GIUSEPPE MARTINO1,*, ANTONINO SICLARI2, SERGIO TRALONGO2 1 Ci.Ma. G.R. e C.A. (Gestione Ricerca e Consulenze Ambientali) - Via Temesa 16, 89131 Reggio Calabria, Italy 2 Ente Parco Nazionale dell’Aspromonte - Via Aurora 1, 89057 Gambarie di S. Stefano in Aspromonte (RC), Italy * Corresponding author: [email protected] In recent decades, the Golden Eagle Aquila chrysaetos ed into seven research zones, with field activities covering population in Italy has been negatively affected by numer- the period December 2015 up to August 2016. For the hab- ous environmental transformations determined through itat analysis, a vegetation map (Spampinato et al. 2008) anthropogenic actions: the gradual abandonment of tradi- was used, by dividing the territory into four environmental tional agricultural practices, together with the remarkable typologies (unsuitable areas, open areas, woods and refor- decline in pasture activity, mainly at higher altitudes, rep- estation) in order to calculate composition and percentages resent some of the threats that directly affect the species of the environmental typologies for each home range. (Mathieu & Choisy 1982, Huboux 1984, Esteve & Materac This research, carried out during the reproductive sea- 1987, Fasce & Fasce 1992, Pedrini & Sergio 2001, 2002). son, allowed to effectively monitor an area of approxi- In an unfavourable context, especially in regions such mately 310 km2, which is reduced slightly when consider- as Calabria, where these negative factors have had consid- ing the overlap between some observation points and the erable intensity, the role of protected areas has proved to be “shadow zones”. -

Scheda Progetto Per L'impiego Di Volontari In

SCHEDA PROGETTO PER L’IMPIEGO DI VOLONTARI IN SERVIZIO CIVILE IN ITALIA Unpli SCN cod. Accr. UNSC NZ01922 Ufficio per il Servizio Civile Nazionale Via Provinciale, 88 - 83020 Contrada (Av) ENTE 1) Ente proponente il progetto: UNPLI NAZIONALE 2) Codice di accreditamento: NZ01922 3) Albo e classe di iscrizione: NAZIONALE 1^ CARATTERISTICHE PROGETTO 4) Titolo del progetto: CASTELLI E FORTEZZE DI CALABRIA 5) Settore ed area di intervento del progetto con relativa codifica (vedi allegato 3): SETTORE PATRIMONIO ARTISTICO E CULTURALE D/03 – VALORIZZAZIONE STORIE E CULTURE LOCALI 1 6) Descrizione dell’area d’intervento e del contesto territoriale entro il quale si realizza il progetto con riferimento a situazioni definite, rappresentate mediante indicatori misurabili; identificazione dei destinatari e dei beneficiari del progetto: Area d’intervento (Comuni coinvolti nel progetto) Il presente progetto prevede un lavoro comune tra Pro Loco e Associazioni operanti da anni nei Comuni sotto elencati. 1 RC Cittanova 2 RC Mammola 3 RC Marina di Gioiosa Jonica 4 RC Motta San Giovanni 5 RC Motta San Giovanni ASSOCIAZIONE EUREKA UNPLI Reggio Calabria 6 RC Motta San Giovanni ENTE CAPOFILA 7 RC Reggio Calabria PRO LOCO SAN SALVATORE 8 RC Saline di Montebello J. 9 RC Samo 10 RC Scido 11 RC Siderno 12 RC Varapodio 13 CS Castrovillari PRO LOCO DEL POLLINO 14 CS Paterno Calabro 15 CS Rende 16 CS Rossano 17 CS San Fili PRO LOCO MBUZATI – JUL 18 CS San Giorgio Albanese VARIBOBBA 19 CZ Cropani 20 CZ Sersale 21 KR Cirò 22 KR Cirò Marina 23 KR Crotone 24 KR Isola Capo Rizzuto 25 KR Santa Severina PRO LOCO SIBERENE 26 VV Francica 27 VV Jonadi 28 VV Limbadi 29 VV Mileto 30 VV Parghelia 31 VV Pizzo San Costantino 34 VV UNPLI Vibo Valentia Calabro 33 VV Tropea 2 34 VV Vazzano La Calabria ha sempre svolto un ruolo strategico nel Mediterraneo. -

I Territori Della Città Metropolitana. Le Aggregazioni a Geometria Variabile

1 Gruppo di lavoro Riccardo Mauro - Vicesindaco Città Metropolitana di Reggio Calabria Fabio Scionti - Consigliere Metropolitano - coordinamento attività Esperti ANCI Esperti ANCI: Maria Grazia Buffon - Erika Fammartino - Raffaella Ferraro - Domenica Gullone Tutti gli elaborati sono frutto di un lavoro comune e condiviso dal Gruppo di lavoro. Elaborazione documento a cura di:Maria Grazia Buffon Elaborazioni e cartografie (ad eccezione di quelle di cui è citata la fonte) a cura di: Maria Grazia Buffon Copertina e grafica a cura di: Erika Fammartino 2 3 I Territori della Città Metropolitana di Reggio Calabria LE AGGREGAZIONI DEI COMUNI A GEOMETRIA VARIABILE Analisi a supporto della tematica inerente alla Governance e al Riordino istituzionale INDICE 1. PREMESSA ................................................................................................................................................ 6 2. AGGREGAZIONI POLITICO-ISTITUZIONALI ................................................................................. 7 2.1.Unione di Comuni ..................................................................................................................................... 7 2.2. Associazioni di Comuni ........................................................................................................................... 9 2.3. I Comuni ricadenti nel Parco Nazionale dell'Aspromonte e i Landscape dell'Aspromonte Geopark ........................................................................................................................................................ -

Urban Form, Public Life and Social Capital - a Case Study of How the Concepts Are Related in Calabria, Italy

EXAMENSARBETE INOM SAMHÄLLSBYGGNAD, AVANCERAD NIVÅ, 30 HP STOCKHOLM, SVERIGE 2019 Urban form, public life and social capital - a case study of how the concepts are related in Calabria, Italy SOFIA HULDT KTH SKOLAN FÖR ARKITEKTUR OCH SAMHÄLLSBYGGNAD Abstract The aim of this thesis is to investigate the urban structure of two Italian towns based upon physical structure and social function. The towns are Bova and Bova Marina in the ancient Greek part of Calabria, Area Grecanica. This is done by answering the research questions about how the urban structures are and what preconditions there are for public life and in extension social capital. This is also compared to the discourse in research about Calabria as a region lacking behind as well as the Greek cultural heritage. The thesis was conducted during one semester spent in the area and based upon qualitative research in form of observations of the towns, mapping, textual analysis and interviews. The results showed that the urban form of the two towns differ from each other because of their history and their localisation. Bova is an ancient town in the mountains that is separated through topography, and therefore conserved with many old structures but few inhabitants, suffering from out-migration. Bova Marina is placed on the coast of the Ionic Sea, south of Bova and connected to the region by train and roads, while Bova is mainly connected to Bova Marina. Bova Marina was founded as a town in late 19th century and expanded a lot because of the railroad. It is a town with inconsistent walking network, a lot of traffic and houses in bad condition. -

Reported Outcome of the Expert Group Meeting on the Management, Use

CAC/COSP/WG.2/2014/CRP.1 8 August 2014 English only Open-ended Intergovernmental Working Group on Asset Recovery Vienna, 11-12 September 2014 Reported outcome of the expert group meeting on the management, use and disposal of frozen, seized and confiscated assets, held in Reggio Calabria, Italy, from 2 to 4 April 2014 V.14-05186 (E) *1405186* REGIONE CALABRIA Management, use and disposal of frozen, seized and confiscated assets (1) Background to the initiative Organized crime groups today, including Mafias, constitute a transnational problem and a threat to security, especially in poor and conflict-ridden countries. Crime is fuelling corruption, infiltrating business and politics, and hindering development. It is also undermining governance by empowering those who operate outside the law. Corruption, coercion and white collar collaborators (in the private and public sectors) ease the activities of transnational criminal organizations, including Mafias, so lowering the risks for the members of these organizations of being investigated, arrested and prosecuted, while the effective logistics they provide increases their profits. This model has made transnational crime one of the world’s most sophisticated and profitable businesses. Consequently, transnational criminal organizations, including Mafias, have amassed vast wealth, which is often manifested in real assets and businesses. Such assets are often held in jurisdictions away from where the groups are located, and beyond the jurisdictional reach of law enforcement agencies in the host country. This necessitates the development of strategies and operational practices to trace, identify and then freeze, seize and confiscate such assets. Once this is achieved, policies and practices to manage frozen and seized assets are necessary while action is taken to ultimately confiscate and, where appropriate, return the assets to their rightful point of origin. -

Middle Oligocene Extension in the Mediterranean Calabro-Peloritan Belt (Southern Italy)

Middle Oligocene extension in the Mediterranean Calabro-Peloritan belt (Southern Italy). Insights from the Aspromonte nappes-pile. Thomas Heymes, Jean-Pierre Bouillin, Arnaud Pecher, Patrick Monié, R. Compagnoni To cite this version: Thomas Heymes, Jean-Pierre Bouillin, Arnaud Pecher, Patrick Monié, R. Compagnoni. Middle Oligocene extension in the Mediterranean Calabro-Peloritan belt (Southern Italy). Insights from the Aspromonte nappes-pile.. Tectonics, American Geophysical Union (AGU), 2008, 27, pp.TC2006. 10.1029/2007TC002157. hal-00283182 HAL Id: hal-00283182 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00283182 Submitted on 29 May 2008 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 1 Middle Oligocene extension in the Mediterranean Calabro-Peloritan belt (Southern 2 Italy). Insights from the Aspromonte nappes-pile. 3 4 Heymes, T., Bouillin, J.-P., Pêcher, A., Monié, P. & Compagnoni, R. 5 6 Abstract 7 The Calabro-Peloritan belt constitutes the eastward termination of the southern segment 8 of the Alpine Mediterranean belt. This orogenic system was built up during the convergence 9 between the Eurasian and the African plates, roughly directed North-South since the Upper 10 Cretaceous. It was subsequently fragmented during the opening of the Western Mediterranean 11 basins since Oligocene times.