Archaeological Practice and Political Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bolivia's 2020 Election: Winning Is Only the Beginning for Luis Arce and The

LSE Latin America and Caribbean Blog: Bolivia’s 2020 election: winning is only the beginning for Luis Arce and the MAS Page 1 of 3 Bolivia’s 2020 election: winning is only the beginning for Luis Arce and the MAS The new MAS government of Luis Arce will be caught between popular expectations of a return to relative prosperity, a growing ecological catastrophe tied to a declining economic model, and a range of social and ideological challenges that pit right-wing religious forces against an increasingly progressive younger generation. But even if the years ahead will show that this victory was in fact the easy part, for now Bolivians have given the world a vital lesson in democracy, writes Bret Gustafson (Washington University in St Louis). Though the official tally is still being finalised, exit polls released around midnight on Sunday 18 October suggest an overwhelming victory for the MAS party in Bolivia, just eleven months after the ouster of Evo Morales. To avoid a run-off, the MAS presidential candidate Luis Arce needed at least 40 per cent of the vote and a ten-point lead over his nearest rival, but this looked like anything but a foregone conclusion in the lead-up to the elections. Luis Arce and his MAS party achieved a sweeping victory just eleven months after Evo Morales was ousted from the presidency (flag removed, Cancillería del Ecuador, CC BY-SA 2.0) Pre-election polling and a divided opposition In the weeks and days before the vote, polling suggested that Carlos Mesa, a right-leaning historian who was briefly president in the early 2000s, stood a good chance of making it to the second round. -

Changing Ethnic Boundaries

Changing Ethnic Boundaries: Politics and Identity in Bolivia, 2000–2010 Submitted by Anaïd Flesken to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Ethno–Political Studies in October 2012 This thesis is available for library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other university. Signature: …………………………………………………………. Abstract The politicization of ethnic diversity has long been regarded as perilous to ethnic peace and national unity, its detrimental impact memorably illustrated in Northern Ireland, former Yugo- slavia or Rwanda. The process of indigenous mobilization followed by regional mobilizations in Bolivia over the past decade has hence been seen with some concern by observers in policy and academia alike. Yet these assessments are based on assumptions as to the nature of the causal mechanisms between politicization and ethnic tensions; few studies have examined them di- rectly. This thesis systematically analyzes the impact of ethnic mobilizations in Bolivia: to what extent did they affect ethnic identification, ethnic relations, and national unity? I answer this question through a time-series analysis of indigenous and regional identification in political discourse and citizens’ attitudes in Bolivia and its department of Santa Cruz from 2000 to 2010. Bringing together literature on ethnicity from across the social sciences, my thesis first develops a framework for the analysis of ethnic change, arguing that changes in the attributes, meanings, and actions associated with an ethnic category need to be analyzed separately, as do changes in dynamics within an in-group and towards an out-group and supra-group, the nation. -

Download Print Version (PDF)

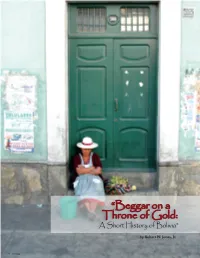

“Beggar on a Throne of Gold: A Short History of Bolivia” by Robert W. Jones, Jr. 6 Veritas is a land of sharp physical and social contrasts. Although blessed with Benormousolivia mineral wealth Bolivia was (and is) one of the poorest nations of Latin America and has been described as a “Beggar on a Throne of Gold.” 1 This article presents a short description of Bolivia as it appeared in 1967 when Che Guevara prepared to export revolution to the center of South America. In Guevara’s estimation, Bolivia was ripe for revolution with its history of instability and a disenfranchised Indian population. This article covers the geography, history, and politics of Bolivia. Geography and Demographics Bolivia’s terrain and people are extremely diverse. Since geography is a primary factor in the distribution of the population, these two aspects of Bolivia will be discussed together. In the 1960s Bolivian society was predominantly rural and Indian unlike the rest of South America. The Indians, primarily Quechua or Aymara, made up between fifty to seventy percent of the population. The three major Indian dialects are Quechua, Aymara, and Guaraní. The remainder of the population were whites and mixed races (called “mestizos”). It is difficult to get an accurate census because The varied geographic regions of Bolivia make it one of the Indians have always been transitory and there are the most climatically diverse countries in South America. cultural sensitivities. Race determines social status in Map by D. Telles. Bolivian society. A mestizo may claim to be white to gain vegetation grows sparser towards the south, where social status, just as an economically successful Indian the terrain is rocky with dry red clay. -

Estudios Bolivianos (No. 26 2017)

Estudios Bolivianos (no. 26 2017) Titulo Villena Alvarado, Marcelo - Autor/a; Souza Crespo, Mauricio - Autor/a; Gantier Autor(es) Zelada, Bernardo - Autor/a; Bridikhina, Eugenia - Autor/a; Medina, Javier - Autor/a; Rossells, Beatriz - Autor/a; Maric P., María Lily - Autor/a; Rivera-Rodas, Oscar - Autor/a; Rodas Morales, Hugo - Autor/a; La Paz Lugar Instituto de Estudios Bolivianos Editorial/Editor 2017 Fecha Colección Historia; Arte; Narrativas; Cultura; Identidad; América Latina; Bolivia; Temas Revista Tipo de documento "http://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar/Bolivia/ieb/20171031043418/Estudios_Bolivianos_26.pdf" URL Reconocimiento-No Comercial-Sin Derivadas CC BY-NC-ND Licencia http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/deed.es Segui buscando en la Red de Bibliotecas Virtuales de CLACSO http://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar Consejo Latinoamericano de Ciencias Sociales (CLACSO) Conselho Latino-americano de Ciências Sociais (CLACSO) Latin American Council of Social Sciences (CLACSO) www.clacso.edu.ar UNIVERSIDAD MAYOR DE SAN ANDRÉS Estudios Bolivianos 26 INSTITUTO DE ESTUDIOS BOLIVIANOS FACULTAD DE HUMANIDADES Y CIENCIAS DE LA EDUCACIÓN Estudios Bolivianos 26 Historia, arte y narrativa contemporáneas Depósito legal: 4-3-97-07 ISSN: 2078-0362 Directora del IEB: Dra. Galia Domic Peredo Coordinación y edición: Dra. Beatriz Rossells Co-edición: Mónica Navia Antezana Correctora de estilo Tania Huanca Cuno Diseño y diagramación: Fernando Diego Pomar Crespo Apoyo logístico: Roxana Espinoza, Andrés Condori Impresión: Editorial Convenio Andrés Bello Portada: Mamagnífica coca, 2011, acuarela del pintor Mario Conde (57x76 cm) Editorial: Instituto de Estudios Bolivianos Tiraje: 300 ejemplares Dirección institucional: Av. 6 de Agosto N° 2080, 2° Piso [email protected] [email protected] Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de la Educación Universidad Mayor de San Andrés Junio de 2017 CONSEJO EDITORIAL Directora del IEB Editores asociados Dra. -

Chain Agriculture

Working 6 Paper BRICS and MICs in Bolivia’s ‘value’-chain agriculture Ben McKay April 2015 1 BRICS and MICs in Bolivia’s ‘value’‐chain agriculture by Ben McKay Published by: BRICS Initiative for Critical Agrarian Studies (BICAS) in collaboration with: Universidade de Brasilia Universidade Estadual Paulista (UNESP) Campus Universitário Darcy Ribeiro Rua Quirino de Andrade, 215 Brasília – DF 70910‐900 São Paulo ‐ SP 01049010 Brazil Brazil Tel: +55 61 3107‐3300 Tel: +55‐11‐5627‐0233 E‐mail: [email protected] E‐mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.unb.br/ Website: www.unesp.br Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul Transnational Institute Av. Paulo Gama, 110 ‐ Bairro Farroupilha PO Box 14656 Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul 1001 LD Amsterdam Brazil The Netherlands Tel: +55 51 3308‐3281 Tel: +31 20 662 66 08 Fax: +31 20 675 71 76 E‐mail: [email protected] E‐mail: [email protected] Website: www.ufrgs.br/ Website: www.tni.org Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies (PLAAS) International Institute of Social Studies University of the Western Cape, Private Bag X17 P.O. Box 29776 Bellville 7535, Cape Town 2502 LT The Hague South Africa The Netherlands Tel: +27 21 959 3733 Fax: +27 21 959 3732 Tel: +31 70 426 0460 Fax: +31 70 426 079 E‐mail: [email protected] E‐mail: [email protected] Website: www.plaas.org.za Website: www.iss.nl College of Humanities and Development Studies Future Agricultures Consortium China Agricultural University Institute of Development Studies No. 2 West Yuanmingyuan Road, Haidian District University of Sussex Beijing 100193 Brighton BN1 9RE PR China England Tel: +86 10 62731605 Fax: +86 10 62737725 Tel: +44 (0)1273 915670 E‐mail: [email protected] E‐mail: info@future‐agricultures.org Website: http://cohd.cau.edu.cn/ Website: http://www.future‐agricultures.org/ ©April 2015 Editorial committee: Jun Borras, Ben Cousins, Juan Liu & Ben McKay Published with support from Ford Foundation and the National Research Foundation of South Africa. -

Issue Information

Juengst and Becker, Editors Editors and Becker, Juengst of Community The Bioarchaeology 28 AP3A No. The Bioarchaeology of Community Sara L. Juengst and Sara K. Becker, Editors Contributions by Sara K. Becker Deborah Blom Jered B. Cornelison Sylvia Deskaj Lynne Goldstein Sara L. Juengst Ann M. Kakaliouras Wendy Lackey-Cornelison William J. Meyer Anna C. Novotny Molly K. Zuckerman 2017 Archeological Papers of the ISSN 1551-823X American Anthropological Association, Number 28 aapaa_28_1_cover.inddpaa_28_1_cover.indd 1 112/05/172/05/17 22:26:26 PPMM The Bioarchaeology of Community Sara L. Juengst and Sara K. Becker, Editors Contributions by Sara K. Becker Deborah Blom Jered B. Cornelison Sylvia Deskaj Lynne Goldstein Sara L. Juengst Ann M. Kakaliouras Wendy Lackey-Cornelison William J. Meyer Anna C. Novotny Molly K. Zuckerman 2017 Archeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association, Number 28 ARCHEOLOGICAL PAPERS OF THE AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION Lynne Goldstein, General Series Editor Number 28 THE BIOARCHAEOLOGY OF COMMUNITY 2017 Aims and Scope: The Archaeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association (AP3A) is published on behalf of the Archaeological Division of the American Anthropological Association. AP3A publishes original monograph-length manuscripts on a wide range of subjects generally considered to fall within the purview of anthropological archaeology. There are no geographical, temporal, or topical restrictions. Organizers of AAA symposia are particularly encouraged to submit manuscripts, but submissions need not be restricted to these or other collected works. Copyright and Copying (in any format): © 2017 American Anthropological Association. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing from the copyright holder. -

Constructing Andean Utopia in Evo Morales's Bolivia

UCC Library and UCC researchers have made this item openly available. Please let us know how this has helped you. Thanks! Title Comparative indigeneities in contemporary Latin America: an analysis of ethnopolitics in Mexico and Bolivia Author(s) Warfield, Cian Publication date 2020 Original citation Warfield, C. 2020. Comparative indigeneities in contemporary Latin America: an analysis of ethnopolitics in Mexico and Bolivia. PhD Thesis, University College Cork. Type of publication Doctoral thesis Rights © 2020, Cian Warfield. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/10551 from Downloaded on 2021-10-09T12:31:58Z Ollscoil na hÉireann, Corcaigh National University of Ireland, Cork Comparative Indigeneities in Contemporary Latin America: Analysis of Ethnopolitics in Mexico and Bolivia Thesis presented by Cian Warfield, BA, M.Res for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University College Cork Department of Spanish, Portuguese and Latin American Studies Head of Department: Professor Nuala Finnegan Supervisor: Professor Nuala Finnegan 2020 Contents Acknowledgements …………………………………………………………………………………………………03 Abstract………………………….……………………………………………….………………………………………….06 Introduction…………………………..……………………………………………………………..…………………..08 Chapter One Tierra y Libertad: The Zapatista Movement and the Struggle for Ethnoterritoriality in Mexico ……………………………………………………………….………………………………..……………………..54 Chapter Two The Struggle for Rural and Urban Ethnoterritoriality in Evo Morales’s Bolivia: The 2011 TIPNIS Controversy -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION CITIZENSHIP IN TWENTIETH- CENTURY ARGENTINA BENJAMIN BRYCE AND DAVID M. K. SHEININ t many moments in the twentieth century, the meaning of citizen- ship in Argentina has changed. In 1912, electoral reform expanded Avoting rights from elite men to include all men born or naturalized in the country.1 Only in 1947 did the franchise expand to include women. Yet, that alone is not the story of Argentine citizenship. When electoral democ- racy was interrupted in 1930, 1943, 1955, 1962, 1966, and 1976, people did not cease to be citizens. When Juan Perón became president in 1946, he cam- paigned heavily on the idea of social justice. During his populist rule, the rights of citizenship came to encompass greater access to social services and housing as well as higher wages. Throughout the century, citizenship—as a concept invoked by diverse groups of people—has defined people’s relation- ship with the state and their expectations about that state. It also shaped the rights and duties of not only Argentines but also foreign nationals living in the country. The language of citizenship was also fundamentally about belonging. Scholars in this volume and beyond use terms such as cultural, moral, and social citizenship. In seeking out these cultural, moral, and social require- ments, groups with power excluded others whose status in Argentine society was vulnerable. Even if formally citizens, workers, indigenous peoples, racial- ized groups, leftists, and religious minorities have often not been included in the Argentine body politic or have not experienced the same rights as others in many periods of the past century. -

Universidade Federal De São Paulo Escola De Filosofia, Letras E Ciências Humanas

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE SÃO PAULO ESCOLA DE FILOSOFIA, LETRAS E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS CECÍLIA GONÇALVES GOBBIS Rebeliões de Cusco e Alto Peru (1780-1783): historiografia, gênero e temática indígena GUARULHOS 2019 CECÍLIA GONÇALVES GOBBIS Rebeliões de Cusco e Alto Peru (1780-1783): historiografia, gênero e temática indígena Trabalho de conclusão de curso apresentado à Universidade Federal de São Paulo como requisito parcial para obtenção do grau em Bacharel em História. Orientador: José Carlos Vilardaga GUARULHOS 2019 Na qualidade de titular dos direitos autorais, em consonância com a Lei de direitos autorais nº 9610/98, autorizo a publicação livre e gratuita desse trabalho no Repositório Institucional da UNIFESP ou em outro meio eletrônico da instituição, sem qualquer ressarcimento dos direitos autorais para leitura, impressão e/ou download em meio eletrônico para fins de divulgação intelectual, desde que citada a fonte. Gobbis, Cecília Gonçalves Rebeliões de Cusco e Alto Peru (1780-1783): historiografia, gênero e temática indígena / Cecília Gonçalves Gobbis. – Guarulhos, 2019 f.65 Trabalho de conclusão de curso (graduação em História) –Universidade Federal de São Paulo, Escola de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas, 2019. Orientador: José Carlos Vilardaga. Título em inglês: Cusco and Upper Peru Rebellions (1780-1783): historiography, gender and indigenous thematic 1.América Colonial 2. Gênero 3. História Indígena I. Vilardaga, José Carlos. II. Trabalho de conclusão de curso (graduação em História) – Universidade Federal de São Paulo, Escola de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas, 2019. III. Rebeliões de Cusco e Alto Peru (1780-1783): historiografia, gênero e temática indígena. CECÍLIA GONÇALVES GOBBIS Rebeliões de Cusco e Alto Peru (1780-1783): historiografia, gênero e temática indígena Trabalho de conclusão de curso apresentado à Universidade Federal de São Paulo como requisito parcial para obtenção do grau em Bacharel em História. -

Mapping Bolivia‟S Socio-Political Climate: Evaluation of Multivariate Design Strategies

MAPPING BOLIVIA‟S SOCIO-POLITICAL CLIMATE: EVALUATION OF MULTIVARIATE DESIGN STRATEGIES A Thesis by CHERYL A. HAGEVIK Submitted to the Graduate School Appalachian State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2011 Department of Geography and Planning MAPPING BOLIVIA‟S SOCIO-POLITICAL CLIMATE: EVALUATION OF MULTIVARIATE DESIGN STRATEGIES A Thesis by CHERYL A. HAGEVIK August 2011 APPROVED BY: ____________________________________ Dr. Christopher A. Badurek Chairperson, Thesis Committee ____________________________________ Dr. Kathleen A. Schroeder Member, Thesis Committee ____________________________________ Dr. James E. Young Member, Thesis Committee ____________________________________ Dr. Kathleen A. Schroeder Chairperson, Department of Geography and Planning ____________________________________ Dr. Edelma D. Huntley Dean, Research and Graduate Studies Copyright by Cheryl A. Hagevik 2011 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT MAPPING BOLIVIA‟S SOCIO-POLITICAL CLIMATE: EVALUATION OF MULTIVARIATE DESIGN STRATEGIES Cheryl A. Hagevik, B.S., Appalachian State University M.A., Appalachian State University Chairperson: Christopher A. Badurek Multivariate mapping can be an effective way to illustrate functional relationships between two or more related variables if presented in a careful manner. One criticism of multivariate mapping is that information overload can easily occur, leading to confusion and loss of map message to the reader. At times, map readers may benefit instead from viewing the datasets in a side-by-side manner. This study investigated the use of multivariate mapping to display bivariate and multivariate relationships using a case example of social and political data from Bolivia. Recent changes occurring in the political atmosphere of Bolivia can be better visualized, understood, and monitored through the assistance of multivariate mapping approaches. -

Current Supply and Demand for Neopopulism in Latin America Gabriela De Oliveira Piquet Carneiro a a University of São Paulo, Brasil Published Online: 26 Jul 2011

This article was downloaded by: [Gabriela Oliveira] On: 08 August 2013, At: 06:35 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK International Review of Sociology: Revue Internationale de Sociologie Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cirs20 Current supply and demand for neopopulism in Latin America Gabriela de Oliveira Piquet Carneiro a a University of São Paulo, Brasil Published online: 26 Jul 2011. To cite this article: Gabriela de Oliveira Piquet Carneiro (2011) Current supply and demand for neopopulism in Latin America, International Review of Sociology: Revue Internationale de Sociologie, 21:2, 367-389, DOI: 10.1080/03906701.2011.581808 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03906701.2011.581808 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

Tupac Amaru and Cata

A b b r e v i a t i o n s a n d Copyright Acknowledgments Coleccion documental de la independencia del Peru. Comision Na- cional del Sesquicentenario de la Independencia del Peru. Lima, 1971. Vol. 2. La Rebelion de Tiipac Amaru. Vol. 2 contains books 1—4 (Tomo 11, Volumen 1-4). Most of the materials are from Vol. 2, books 2-3. The references in the work are to document numbers, not page numbers. Vol. 2, book 2 contains numbers 1-206 Vol.2, book 3 contains numbers 207-327. The Last Inca Revolt^ 1780-1783. Lillian Estelle Fisher. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1966. Rebellions and Revolts in Eightee7tth Century Peru and Upper Peru. Scarlett O'Phelan Godoy. Koln: Bohlau Verlag, 1985. Reprinted by permission of the publisher. La rebelion de Tupac Amaru y los origenes de la independencia de his- panoamerica. Boleslao Lewin. Buenos Aires: Sociedad Editora Latino Americana, 1967. Subverting Colonial Authority. Challenges to Spanish Rule in Eigh- teenth-Century Southern Andes. Sergio Serulnikov. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003. Selections from SCA appear on pages 170-73, 176, 179-86, 201, 205-7, 208-10, and 212-14. Re printed by permission of the publisher. We Alone Will Rule: Native Andean Politics in the Age of Insurgency. Sinclair Thomson. © 2003. Reprinted by permission of The Uni versity of Wisconsin Press. Tn eWorld of Tupac Amaru: Conflict, Community and Identity in Colo nial Peru. Ward Stavig. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1999. Reprinted by permission of the University of Nebraska Press. © 1999 by the University of Nebraska Press.