Roaring Twenties

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Handsome Johnny) Roselli Part 6 of 12

FEDERAL 1-OF TNVEESTIGAFHON JOHN ROSELLI EXCERPTS! PART 2 OF 5 e --. K3 ,~I FEDERAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION Q Form No. 1 _ 4. Tr-us castORIGINATED AT §'fA,3H_[_NG1D1qiQ: FILE ]_]& NO. IIOITHADIAT . '1.. ' » 'DATIWHINMADI I PERIOD!-ORWHICH MADE E I 1, ' Is, TENT!sss 10-s-4'? 110- I. - CHARACTIR OF CA-BE %I LOUISc%:mAc1n., was,er AL sznssar P1'".ROLE TQTTER _ ___ . ._ . est . SYNOPSIS OF FACTS: Judge T. sasBEa92t*ILsoN statesletters received from priests and citizens in Chicago recommending subjects be paroled were accepted in good faith, and inquiries were not made relative to character and reputation of persons from whom letters received. states EldVi5eIS for_§ll five subjects were investigated by Chief Pro- bation Officer, Chicago, Illinois. Judge WILSONdenies knogng adviers. Judge WIISONhad been contacted by a I I if I I .- numhbr of Congressmen relative to paroling of prisoners, buttas not contacted by any Congressmanin instant ' I -» '-1,. ._ . case. Judge WILSON had been contacted by officials in e Department regarding paroling of prisoners, but was=not contacted by anyone in the Department in con- nec¬Eon with the subjects of this case. Judge'WllSON states that whenever recommendations of Congressmen and officials of Department were not inconsistent with facts and merits of case under consideration, he went along with their suggestions. Judge WILSON emphasized, however, that his decision.with respect to the paroling of any individual had never been influenced by a Con- gressman, an official of the Department, or anyone else. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 106 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 106 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 145 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, MAY 4, 1999 No. 63 House of Representatives The House met at 12:30 p.m. tainted water supply cleaned up, the into effect, and they still will not f guilty must be found, and they must be admit, is that MTBE is a powerful and punished. persistent water pollutant and, from MORNING HOUR DEBATES Now this perhaps sounds like a Holly- leaks and spills, has made its way into The SPEAKER. Pursuant to the wood plot, a Hollywood movie, but it is groundwater of nearly every State in order of the House of January 19, 1999, not, and for many communities across this Nation; the problem, of course, the Chair will now recognize Members this Nation, they are facing this situa- being worse in California, the har- from lists submitted by the majority tion. The guilty party is none other binger of what will surely come to pass and minority leaders for morning hour than the supposed protector, the Envi- in much of the rest of this country. It debates. The Chair will alternate rec- ronmental Protection Agency. takes only a small amount of MTBE to ognition between the parties, with each Tom Randall, a managing editor of make water undrinkable. It spreads party limited to 30 minutes, and each the Environmental News, recently rapidly in both groundwater and res- Member, except the majority leader, brought some articles to my attention. -

Galveston's Balinese Room

Official State Historical Center of the Texas Rangers law enforcement agency. The Following Article was Originally Published in the Texas Ranger Dispatch Magazine The Texas Ranger Dispatch was published by the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum from 2000 to 2011. It has been superseded by this online archive of Texas Ranger history. Managing Editors Robert Nieman 2000-2009; (b.1947-d.2009) Byron A. Johnson 2009-2011 Publisher & Website Administrator Byron A. Johnson 2000-2011 Director, Texas Ranger Hall of Fame Technical Editor, Layout, and Design Pam S. Baird Funded in part by grants from the Texas Ranger Association Foundation Copyright 2017, Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum, Waco, TX. All rights reserved. Non-profit personal and educational use only; commercial reprinting, redistribution, reposting or charge-for- access is prohibited. For further information contact: Director, Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum, PO Box 2570, Waco TX 76702-2570. Galveston’s Balinese Room Galveston’s Balinese Room Born: 1942 – Died 2008 The Balinese Room was built on a peer stretching 600 feet into the Gulf of Mexico. Robert Nieman © All photos courtesy of Robert Nieman unless otherwise noted. For fifteen years, Galveston’s Balinese Room was one of the most renowned and visited gambling casinos in the world. Opened in 1942 by the Maceo brothers, it flourished until 1957, when the Texas Rangers shut it down permanently as a gambling establishment. In the times that followed, the building served as a restaurant, night club, and curiosity place for wide-eyed visitors. Mainly, though, it sat closed with its door locked—yes, it had only one door. -

The Balinese Room

The Destruction of a Galveston, Texas Landmark by Ed Hertel On September 13, 2008, the residents of Galveston, Texas, woke up and emerged from their wind battered homes to find an island of devastation. Hurricane Ike had made landfall and brought all the fury of a Category 4 storm unto the island. Across the country, stories and images of the weather beaten community flashed across televisions. News reporters stood by piles of rubble, water and complete chaos trying to convey the utter devastation and loss of the city. As the disaster toll rose, a better picture emerged as to what was lost; including hundreds of homes, businesses, hotels and one very important historical landmark. 64 Casino Chip and Token news | Volume 22 Number 2 Almost as an after thought, the news reported on the rim with cases would anchor outside of federal limits destruction of the Balinese Room. It was described as and be unloaded by smaller, faster boats which raced the a nightclub, a Prohibition gambling joint, and a local Coast Guard in a game of cat and mouse. Once these boats “curiosity”. None of these reports fully explained the made it to the beach, they were unloaded onto trucks and significance of this structure in the history of Galveston or distributed throughout the dry country. its influence on gambling. Two very enterprising Sicilian immigrant brothers The story of the Balinese Room is so intertwined with named Salvatore “Sam” and Rosario “Rose” Maceo ran Galveston gambling history it is impossible to mention one what was known as the Beach Gang. -

Praying Against Worldwide Criminal Organizations.Pdf

o Marielitos · Detroit Peru ------------------------------------------------- · Filipino crime gangs Afghanistan -------------------------------------- o Rathkeale Rovers o VIS Worldwide § The Corporation o Black Mafia Family · Peruvian drug cartels (Abu SayyafandNew People's Army) · Golden Crescent o Kinahan gang o SIC · Mexican Mafia o Young Boys, Inc. o Zevallos organisation § Salonga Group o Afridi Network o The Heaphys, Cork o Karamanski gang § Surenos or SUR 13 o Chambers Brothers Venezuela ---------------------------------------- § Kuratong Baleleng o Afghan drug cartels(Taliban) Spain ------------------------------------------------- o TIM Criminal o Puerto Rican mafia · Philadelphia · TheCuntrera-Caruana Mafia clan § Changco gang § Noorzai Organization · Spain(ETA) o Naglite § Agosto organization o Black Mafia · Pasquale, Paolo and Gaspare § Putik gang § Khan organization o Galician mafia o Rashkov clan § La ONU o Junior Black Mafia Cuntrera · Cambodian crime gangs § Karzai organization(alleged) o Romaniclans · Serbian mafia Organizations Teng Bunmaorganization § Martinez Familia Sangeros · Oakland, California · Norte del Valle Cartel o § Bagcho organization § El Clan De La Paca o Arkan clan § Solano organization Central Asia ------------------------------------- o 69 Mob · TheCartel of the Suns · Malaysian crime gangs o Los Miami o Zemun Clan § Negri organization Honduras ----------------------------------------- o Mamak Gang · Uzbek mafia(Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan) Poland ----------------------------------------------- -

Trxtto Bstrurr See It

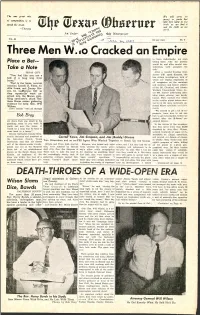

The one great rule We will serve no group or party but of composition is to ill hew hard to the speak the truth. truth as we firsti it and the right as t' —Thoreau Trxtto bstrurr see it. An Incier .000 co,0 c:kly News pa per vol. 49 10c per copy No. 5 9St,e(te:es-c)16" ____:`47- V‘S- 7 Three Men Cracked an Empire to them individually, not even Place a Bet-- telling them who his partner would be, and after careful con- sideration, both accepted the Take a Note task." TEXAS CITY After a careful briefing from "You feel like you are a former FBI agent Simpson, the hell of a long way from two citizen investigators, both of home." whom are regular employees of That is the tense, nervous cil companies on the mainland reaction Carroll S. Yaws, 37, and members and former officers Alta Loma, and Jimmy Giv- of the Oil, Chemical, and Atomic ens, 33, LaMarque, felt as Workers International Union Lo- they repeatedly went un- cal 499, started infiltrating gam- armed into the Maceo gam- bling joints, saloons, and bawdy bling syndicate's plush Bal- houses. They worked two weeks inese Room casino gathering in the smaller places before mov- evidence for Atty. Gen. Will ing in on the more cautiously op- Wilson. erated Maceo syndicate est .b'ish- Yaws recalls: "You go through ments. "We wanted to get a bit of ex- perience, learn how to act and Bob Bray how to get information, before we started after the B-Room," ex- six doors from one street to the plained Givens. -

Island Empire: the Influence of the Maceo Family in Galveston

ISLAND EMPIRE: THE INFLUENCE OF THE MACEO FAMILY IN GALVESTON Tabitha Nicole Boatman, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2014 APPROVED: Scott Belshaw, Committee Chair Chad Trulson, Committee Member Richard B. McCaslin, Committee Member Eric Fritsch, Chair of the Department of Criminal Justice Thomas Evenson, Dean of the College of Public Affairs and Community Service Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Boatman, Tabitha Nicole. Island Empire: The Influence of the Maceo Family in Galveston. Master of Science (Criminal Justice), August 2014, 127 pp., bibliography, 80 titles. From the 1920s until the 1950s, brothers, Sam and Rosario Maceo, ran an influential crime family in Galveston, Texas. The brothers’ success was largely due to Galveston’s transient population, the turbulent history of the island, and the resulting economic decline experienced at the turn of the 20th century. Their success began during Prohibition, when they opened their first club. The establishment offered bootlegged liquor, fine dining, and first class entertainment. After Prohibition, the brothers continued to build an empire on the island through similar clubs, without much opposition from the locals. However, after being suspected of involvement in a drug smuggling ring, the Maceos were placed under scrutiny from outside law enforcement agencies. Through persistent investigations, the Texas Rangers finally shut down the rackets in Galveston in 1957. Despite their influence through the first half of the 20th century, on the island and off the island, their story is largely missing from the current literature. Copyright 2014 by Tabitha Nicole Boatman ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my deepest appreciation to my thesis committee members, particularly Dr. -

Thanks for the Memories

Thanks for the Memories The Hotel Galvez and Spa lives eternally in the memories of thousands of people who have been its guests over a century. The following are a few of the mementoes they have shared with us. ———————— 1915 Lawrence A. Wainer Dallas, Texas My father, Max Wainer Sr., was born in the Hotel Galvez, in Room 231, during the 1915 storm. (Room 231 was located where the elevator bank now stands.) I have a copy of his birth certificate and a letter from the general manager of the Hotel Galvez, written in 1915, congratulating the parents on the new arrival and assuring them that the Hotel Galvez would take care of them. ———————— 1926 Dr. E. Sinks McLarty Galveston, Texas We moved to the Galvez in 1926, when I was about five. The hotel back then had a lot of permanent residents. Times were hard and a lot of peo- ple worked for the hotel and lived there, too. Pop was the hotel doctor. Even though my dad was the doctor, we were too poor to eat at the hotel. We got our meals at a boarding house a few blocks away. You learn to eat fast at a boarding house. We lived in three rooms in the middle section of the sixth floor, on the south side, overlooking the Gulf. Sam Maceo had his penthouse on the floor just above us. Sam was a good man, really nice to me. He had a nephew about my age who stayed at the Galvez sometimes. His nephew had a secret hiding place inside one of the closets where you could look into people’s bedrooms, but I was always afraid to go with him. -

"Through Hazel Eyes" : Hazel Brannon Smith's Fight for Free Speech and Justice in Mississippi 1936-1985

Mississippi State University Scholars Junction Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 12-1-2013 "Through Hazel Eyes" : Hazel Brannon Smith's Fight for Free Speech and Justice in Mississippi 1936-1985 Jeffery Brian Howell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsjunction.msstate.edu/td Recommended Citation Howell, Jeffery Brian, ""Through Hazel Eyes" : Hazel Brannon Smith's Fight for Free Speech and Justice in Mississippi 1936-1985" (2013). Theses and Dissertations. 8. https://scholarsjunction.msstate.edu/td/8 This Dissertation - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Scholars Junction. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholars Junction. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Automated Template A: Created by James Nail 2011 V2.02 “Through Hazel Eyes”: Hazel Brannon Smith’s fight for free speech and justice in Mississippi 1936-1985 By Jeffery Brian Howell A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Mississippi State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Department of History Mississippi State, Mississippi December 2013 Copyright by Jeffery Brian Howell 2013 “Through Hazel Eyes”: Hazel Brannon Smith’s fight for free speech and justice in Mississippi 1936-1985 By Jeffery Brian Howell Approved: ____________________________________ James C. Giesen (Director of Dissertation) ____________________________________ Jason M. Ward (Committee Member) ____________________________________ Anne E. Marshall (Committee Member) ____________________________________ Michael V. Williams (Committee Member) ____________________________________ Peter C. Messer (Graduate Coordinator) ____________________________________ Greg Dunaway Dean College of Arts & Sciences Name: Jeffery Brian Howell Date of Degree: December 14, 2013 Institution: Mississippi State University Major Field: History Major Professor: James C. -

From Harvard to Enron

http http://www.newsmakingnews.com/lm4,4,02,harvardtoenronpt2.htm NEWSMAKINGNEWS.COM FOLLOW THE YELLOW BRICK ROAD: FROM HARVARD TO ENRON PART TWO by Linda Minor © 2002 Permission to reprint with acknowledgement, granted by author Why Did Pug Go Bananas? We learned from Part One (Click) that Pug Winokur began working in 1974 for David H. Murdock's companies based in Los Angeles, CA. We also looked at information indicating that during the time Pug was at Murdock's Pacific Holding Corp., that company acquired 100% of the stock in International Mining Company--the largest shareholder of Zapata common stock. Two directors of ITC were closely connected to AtlanticRichfield, one director a long-time employee of Shell Oil. There were also close connections to First City Bank of Houston, which a Congressional investigation in 1976 found to be heavily immersed in influence from the Rothschild Bank of London.(1) Between the years of 1966 (when George H.W. Bush resigned as chairman and CEO of Zapata Offshore) and 1974 (when Pug went to work for Murdock), Zapata, the management of which interlocked with that of AtlanticRichfield, (2) was attempting to acquire control of United Fruit Company. Understanding United Fruit's real history, and its financing apparatus through an international investment consortium that dates back at least 100 years, brings Pug's role in that takeover attempt into sharper focus. That history is set out more thoroughly in Part Two-A. Click and Part Two-B Click. After Zapata lost its attempted takeover and accepted greenmail from United Fruit in 1969, Eli Black took charge of United Fruit. -

This Is No Crab Shack

WE OFTEN THINK OF GALVESTON IN THE PAST THIS IS NO TENSE—THE CITY THAT “WAS,” ACCORDING TO HOWARD BARNSTONE’S WELL-KNOWN HOMAGE TO CRAB SHACK ITS VICTORIAN ARCHITECTURE IN HIS BOOK THE GALVESTON THAT WAS (1966). WE RARELY THINK OF IT AS “MODERN.” HOWEVER, GALVESTON, LIKE Sam Maceo’s Modern House HOUSTON, HAS A REMARKABLE HERITAGE OF MODERN am Maceo was born in Palermo, “Rose” Maceo (1887–1954), to Galveston where they Hollywood Dinner Club on 61st Street and Avenue S. Sicily, and emigrated with his both worked as barbers. Rose’s chair was on Designed in the romantic Spanish colonial revival family in 1901 to Leesville, Murdoch’s Pier, the hangout of Ollie Quinn’s Beach style by Galveston architect R. Rapp, it was reported 20 Louisiana, where he worked in Gang, with whom he and his brother soon became to have been the fi rst air-conditioned nightclub and a sawmill. He was later sent to acquainted. By the fi rst years of Prohibition, the casino in the United States. After it was shut down in .cite New Orleans to be trained as a industrious Maceo brothers had become an integral 1939, the Maceo brothers moved their main barber. In 1910 he moved with component of the Beach Gang’s bootlegging operations to a former Chinese restaurant, the Sui !""#$%&'&(#)*+#,&-(% FALL2010 Shis older brother, Rosario operations. In 1926 they opened the 500-seat Jen, built on top of an old wooden pier jutting 600 ARCHITECTURE THAT SOMETIMES RISES TO THE LEVEL OF GENIUS. ONE OF ITS MOST COMPELLING EXAMPLES OF MODERN ARCHITECTURE IS THE HOUSE THAT GALVESTON’S SICILIAN-AMERICAN ORGANIZED CRIME BOSS SALVATORE “SAM” MACEO (1894–1951) BUILT FOR HIS FAMILY IN THE EARLY 1950S IN THE EXCLUSIVE CEDAR LAWN COMMUNITY. -

TRAFFIC in OPIUM and OTHER Dangerous DRUGS

ommunicated to C ,469 .M.318.1938.XI. e council and (O.C ./A.R. 1937/97) e Members of the (issued in English only). ague). Geneva, November 28th, 1938 . LEAGUE OF NATIONS. TRAFFIC IN OPIUM AND OTHER dangerous DRUGS. ANNUAL REPORTS BY GOVERNMENTS FOR 1937„ UNITED STATES OF AMERICA. iote by the Secretary-General, In accordance with Article 21 of the Convention f 1931 for limiting the Manufacture and regulating is Distribut ion of Narcotic Drugs, the Secretary- neral has the honour to communicate herewith to the rties to the Convention the above-mentioned eport. The report is also communicated to other tates and to the Advisory Committee on Traffic in pi urn and other Dangerous Drugs „ (For the form of annual reports., see document O.C.1600). V •IV. C7 * XU • lu UW *AX » (O.C/A.R.li)37/97) Anner'J i TRAFFIC IN OPIUM AND OTHER DANGEROUS DRUGS FOR THE YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31 1937 U. S. TREASURY DEPARTMENT BUREAU OF NARCOTICS WASHINGTON. D . C. U. S. TREASURY DEPARTMENT BUREAU OF NARCOTICS TRAFFIC IN OPIUM AND OTHER DANGEROUS DRUGS FOR THE YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 1937 REPORT BY THE GOVERNMENT OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1938 the Superintendent of Documenta, Washington, D. C, .......................... Price TABLE OF CONTENTS A. GENERAL P ag» I. New legislation_______________________________________________ 1 An Act to Increase the Punishment of Second, Third, and Sub sequent Offenders against the Narcotic Laws______________ 2 New administrative regulations and orders__________________ 2 Uniform Narcotic Drug Act________________________________ 3 II. Administration_______________________________________________ 4 Organization______________________________________________ 4 Drug addiction____________________________________________ 4 III.