Conclusions and Recommendations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aalseth Aaron Aarup Aasen Aasheim Abair Abanatha Abandschon Abarca Abarr Abate Abba Abbas Abbate Abbe Abbett Abbey Abbott Abbs

BUSCAPRONTA www.buscapronta.com ARQUIVO 35 DE PESQUISAS GENEALÓGICAS 306 PÁGINAS – MÉDIA DE 98.500 SOBRENOMES/OCORRÊNCIA Para pesquisar, utilize a ferramenta EDITAR/LOCALIZAR do WORD. A cada vez que você clicar ENTER e aparecer o sobrenome pesquisado GRIFADO (FUNDO PRETO) corresponderá um endereço Internet correspondente que foi pesquisado por nossa equipe. Ao solicitar seus endereços de acesso Internet, informe o SOBRENOME PESQUISADO, o número do ARQUIVO BUSCAPRONTA DIV ou BUSCAPRONTA GEN correspondente e o número de vezes em que encontrou o SOBRENOME PESQUISADO. Número eventualmente existente à direita do sobrenome (e na mesma linha) indica número de pessoas com aquele sobrenome cujas informações genealógicas são apresentadas. O valor de cada endereço Internet solicitado está em nosso site www.buscapronta.com . Para dados especificamente de registros gerais pesquise nos arquivos BUSCAPRONTA DIV. ATENÇÃO: Quando pesquisar em nossos arquivos, ao digitar o sobrenome procurado, faça- o, sempre que julgar necessário, COM E SEM os acentos agudo, grave, circunflexo, crase, til e trema. Sobrenomes com (ç) cedilha, digite também somente com (c) ou com dois esses (ss). Sobrenomes com dois esses (ss), digite com somente um esse (s) e com (ç). (ZZ) digite, também (Z) e vice-versa. (LL) digite, também (L) e vice-versa. Van Wolfgang – pesquise Wolfgang (faça o mesmo com outros complementos: Van der, De la etc) Sobrenomes compostos ( Mendes Caldeira) pesquise separadamente: MENDES e depois CALDEIRA. Tendo dificuldade com caracter Ø HAMMERSHØY – pesquise HAMMERSH HØJBJERG – pesquise JBJERG BUSCAPRONTA não reproduz dados genealógicos das pessoas, sendo necessário acessar os documentos Internet correspondentes para obter tais dados e informações. DESEJAMOS PLENO SUCESSO EM SUA PESQUISA. -

Version 2019, 13 July, 2021 This Is a List of the 10513 Authors With

Version 2019, 27 September, 2021 This is a list of the 10513 authors with Pawlak number 5. Please send corrections and comments to [email protected] A LIST WITH PAWLAK NUMBER 5 Surname and first name: 1. Abawajy Jemal 2. Abbass Safia 3. Abbass Hussein A. 4. Abbass Hussein 5. Abdelbar Ashraf M. 6. Abdelwahab Sherif 7. Abdi Hamid 8. Abdullah Noraswaliza 9. Abdullah Mohd Zaki 10. Abdullah Saleem 11. Abdulmula Karema S. 12. Abdulrahman Ruqayya 13. Abe Masaaki 14. Abeel Thomas 15. Abellnull Alberto 16. Aberer Karl 17. Abhayaratne Charith 18. Abib Elbio Renato Torres 19. Abida Kacem 20. Abidi I. Z. 21. Abielmona Rami S. 22. Abielmona R. 23. Abielmona Rami 24. Abiko Naofumi 25. Abramson Myriam 26. Abrougui Kaouther 27. Abu-halaweh Na'el 28. Abu-Hanna Ameen 29. Abu-Khalaf Murad 30. Acharyya Sreangsu 31. Acosta Maria Luisa 32. Adali Sibel 33. Adali Tnulllay 34. Adamopoulos Miltiades 35. Adams William 36. Adams Rod 37. Adamu Abdullahi S. 38. Adedoyin-Olowe Mariam 39. Adelson Beth 40. Adibi Jafar 41. Adriaans Pieter W. 42. Afsari Fatemeh 43. Agagliati Enzo 44. Agamennoni Gabriel 45. Agarwal Ramesh K. 46. Agarwal Nipun 47. Agashe Bhalchandra 48. Ager Joel 49. Agrawal Vikas 50. Agrawal Ankur 51. Agrawal Divyakant 52. Agrawala Ashok K. 53. Agre Philip E. 54. Aguilar Leocundo 55. Aguilera J. 56. Aguirre Arturo Hernnullndez 57. Aguirre Luis Antonio 58. Aguzzoli Stefano 59. Aha David 60. Ahmad Subutai 61. Ahmad Bashir 62. Ahmad Mohiuddin 63. Ahmad Uzair 64. Ahmad Iftekhar 65. Ahmadian Yashar 66. Ahmed Maher 67. Ahmed M. -

Epos Bundels Junie 2013

SA-GENEALOGIE Poslys Argiewe 2013 Jaargang X Maand 6 Junie 2013 Saamgestel deur: Elorina du Plessis KWYTSKELDING Hierdie argief is nie ’n amptelike, wetlike dokument nie, maar ’n samestelling van die e-posse van verskillende lede van die SA Genealogie Gesprekslys soos dit gedurende die tydperk ingestuur was. Die lyseienaars en hulle bestuurspan aanvaar dus geen aanspreeklikheid vir die korrektheid van gegewens, sienings oor bepaalde gebeure, interpretasie en samestelling van familieverwantskappe, of vir enige aksies of verlies wat daaruit mag voortspruit nie, en stel voor dat persone wat hierdie bron gebruik, self eers die gegewens kontroleer. Junie 2013 Bundels (Zomermaand) Onderwerp: [SA-Gen] Bundel Nommer 6050 Datum: Sat Jun 1, 2013 Daar is 1 boodskappe in hierdie uitgawe Onderwerpe in hierdie bundel: 1a Re: Wonder net oor Wynand Bezuidenhout se geboorte datum. by "Connie Griessen" griessenc Message 1a Re: Wonder net oor Wynand Bezuidenhout se geboorte datum. Sat Jun 1, 2013 2:36 am (PDT) . Posted by: "Connie Griessen" griessenc Ek waardeer jou hulp en bydraes verskriklik - al jou ondervinding in hierdie onderwerp maak vordering soveel vinniger! Lekker dag (wanneer jy weer daglig sien) en groete van 'n sopnat Kaapstad Connie ________________________________ From: Lee McGovern <[email protected]> To: [email protected] Sent: Saturday, June 1, 2013 10:01 AM Subject: RE: [SA-Gen] Wonder net oor Wynand Bezuidenhout se geboorte datum. Dankie. Het gewonder Ek gaan nou sluit voior ek foute maak. Is sif. Dit is nou 8pm hier Groete Lee -------Original Message------- From: Annelie Els Date: 1/06/2013 6:30:42 p.m. To: [email protected] Subject: RE: [SA-Gen] Wonder net oor Wynand Bezuidenhout se geboorte datum. -

00 Dissertation in Full.Docx

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The War People The Daily Life of Common Soldiers 1618-1654 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Lucian Edran Staiano-Daniels 2018 © Copyright by Lucia Eileen Staiano-Daniels 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The War People The Daily Life of Common Soldiers 1618-1654 by Lucia Eileen Staiano-Daniels Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor David Sabean, Chair This dissertation aims to depict the daily life of early seventeenth-century common soldiers in as much detail as possible. It is based on intensive statistical study of common soldiers in Electoral Saxony during the Thirty Years War, through which I both analyze the demographics of soldiers’ backgrounds and discuss military wages in depth. Drawing on microhistory and anthropology, I also follow the career of a single regiment, headed by Wolfgang von Mansfeld (1575-1638), from mustering-in in 1625 to dissolution in 1627. This regiment was made up largely of people from Saxony but it fought in Italy on behalf of the King of Spain, demonstrating the global, transnational nature of early-modern warfare. My findings upend several assumptions about early seventeenth-century soldiers and war. Contrary to the Military Revolution thesis, soldiers do not appear to have become more disciplined during this period, nor was drill particularly important to their daily lives. Common soldiers also took an active role in military justice. -

Global Strategies to Reduce the Health-Care Burden of Craniofacial Anomalies

Global strategies to reduce t Global strategies to reduce the health-care burden of he healt craniofacial anomalies h-care burden of craniofacial ano Report of WHO meetings on International Collaborative Research on Craniofacial Anomalies Geneva, Switzerland, 5-8 November 2000 Park City, Utah, USA, 24-26 May 2001 malies Human Genetics Programme, 2002 Management of Noncommunicable Diseases World Health Organization WHO Geneva, Switzerland ISBN 92 4 159038 6 Global strategies to reduce the health-care burden of craniofacial anomalies Report of WHO meetings on International Collaborative Research on Craniofacial Anomalies Geneva, Switzerland, 5-8 November 2000 Park City, Utah, USA, 24-26 May 2001 Human Genetics Programme – 2002 Management of Noncommunicable Diseases World Health Organization Geneva, Switzerland THIS REPORT IS DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF DR DAVID BARMES, A FORMER STAFF MEMBER OF THE WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION AND FOUNDER OF THE INTERNATIONAL COLLABORATIVE RESEARCH PROJECT ON CRANIOFACIAL ANOMALIES. Acknowledgements: These meetings were organized by the World Health Organization, with financial support from the National Insititute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) of the National Institutes of Health (United States). In particular, the participants of the meetings wish to express their sincere thanks to Dr Kevin Hardwick and Dr Rochelle Small from NIDCR for their support and advice. WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Global strategies to reduce the health-care burden of craniofacial anomalies : report of WHO -

Climate Evolution, Variability and Sensitivity

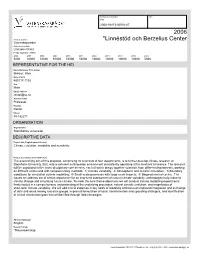

Kansliets noteringar Dnr Kod 2006-16873-36510-47 2006 Area of science *Linnéstöd och Berzelius Center Vetenskapsrådet Announced grants Linnaeus Grant Funds applied for (kSEK) 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 5000 10000 10000 10000 10000 10000 10000 10000 10000 10000 5000 REPRESENTATIVE FOR THE HEI Name(Surname, First name) Bremer, Kåre Date of birth 480117-1192 Sex Male Email address [email protected] Academic title Professor Position Rektor Phone 08-162271 ORGANISATION Organisation Stockholms universitet DESCRIPTIVE DATA Project title, English (max 200 char) Climate evolution, variability and sensitivity Project description (max 1500 char) The overarching aim of this proposal, comprising 26 scientists at four departments, is to further develop climate research at Stockholm University (SU), into a coherent cutting-edge environment consistently operating at the forefront of science. The research will be organized in five cross-disciplinary core themes, each of which brings together scientists from different departments, working on different scales and with complementary methods: 1/ Climate variability; 2/ Atmospheric and oceanic circulation; 3/ Boundary conditions for circulation system modelling; 4/ Small-scale processes with large-scale impacts; 5/ Biogeochemical cycles. The issues we address are of critical importance for an improved assessment of natural climate variability, anthropogenically-induced climate change and simulating future climate. To meet the core theme objectives we will conduct climate modelling experiments firmly rooted in a comprehensive understanding of the underlying processes, natural climatic evolution, and magnitudes of short-term climate variability. We will add critical expertise in key fields of modeling and focus on improved integration and exchange of data and ideas among research groups, improved formulation of scale transformation and upscaling strategies, and identification of critical information gaps that will be filled through field campaigns. -

The Bendectin Litigation: a Case Study in the Life Cycle of Mass Torts Joseph Sanders

Hastings Law Journal Volume 43 | Issue 2 Article 2 1-1992 The Bendectin Litigation: A Case Study in the Life Cycle of Mass Torts Joseph Sanders Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Joseph Sanders, The Bendectin Litigation: A Case Study in the Life Cycle of Mass Torts, 43 Hastings L.J. 301 (1992). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol43/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Bendectin Litigation: A Case Study in the Life Cycle of Mass Torts by JOSEPH SANDERS* Table of Contents I. Introduction ............................................ 303 II. Case Congregations ..................................... 305 A. Beyond the Individual Case ......................... 305 B. Case Congregations and Mass Torts ................. 307 C. A Note on Case Studies ............................. 310 III. Bendectin Background .................................. 311 A. The Firm .......................................... 311 B. The Drug .......................................... 312 (1) Thalidomide ................................... 313 (2) M ER/29 ....................................... 315 (3) Bendectin ...................................... 317 IV. The Science -

Produce Consumption Patterns

PRODUCE CONSUMPTION PATTERNS AMONG PREGNANT WOMEN IN DELAWARE: HEALTH, INCOME, AND POLICY IMPLICATIONS by Erin Dugan A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Degree in Public Policy with Distinction Spring 2016 © Year Author All Rights Reserved 1 1 Produce Consumption Patterns Among Pregnant Women In Delaware: Health, Income, and Policy Implications by Erin Dugan Approved: Daniel Rich, Ph.D. Professor in charge of thesis on behalf of the Advisory Committee Approved: Erin Knight, Ph.D. Committee member from the Department of Public Policy Approved: Avron Abraham, Ph.D. Committee member from the Board of Senior Thesis Readers 2 2 Approved: Michael Arnold, Ph.D. Director, University Honors Program 3 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I owe a great deal of thanks to my undergraduate thesis committee. Throughout this process, they have offered me incredible guidance, and I am so grateful for their expertise. I would also like to acknowledge the help of Mary Joan McDuffie of the Health Services Policy Research Group for possessing a wealth of knowledge on health databases and advising my data usage efforts. A special thanks goes to Dr. Erin Knight, who exposed me to the study of public health and stood by me at every step of my undergraduate career, providing me with academic opportunities, research opportunities, and internship opportunities. Dr. Knight, you cemented my passion for social change by sharing yours, and I cannot thank you enough. I would also like to thank my friends and family, who have given me all the support that I could have ever asked for in the past year. -

Role of Environment In

Global strategies to reduce the health-care burden of craniofacial anomalies Role of environment 4 in CFA 4.1 Socioeconomic status and orofacial clefts The investigation of the relationship between socioeconomic status and the prevalence of various health outcomes has provided important clues as to etiology. For example, the observation of an increasing risk of neural tube defects with decreasing socioeconomic status was one of the clues to a dietary hypothesis for these defects (Elwood and Colquhoun, 1992). Little attempt has been made to investigate whether the risk of orofacial clefts varies by socioeconomic status. Womersley and Stone (1987) examined the prevalence at birth of orofacial clefts within Greater Glasgow (Scotland) during the period 1974-1985, according to housing and employment characteristics recorded in the 1981 census. The highest rates were observed in areas with high proportions of local authority housing with young families, high unemployment and a preponderance of unskilled workers, whereas the lowest rates were found in affluent areas with high proportions of professional and non-manual workers in large owner-occupied or high-quality housing. Most of this pattern was accounted for by CP, with less variation in CL/P. A variety of different indicators of socioeconomic status have been developed (Liberatos et al., 1988). In an international context, it seems appropriate to use one that is specific to the local area, and one that can be compared between countries, e.g. years of schooling. As socioeconomic status can be difficult to determine at the level of the individual, especially for women, there has been increasing interest in developing, and using, area-based measures of material deprivation as a proxy for socioeconomic status (Townsend,1987; Carstairs and Morris, 1990). -

Pre-Conceptional Vitamin Supplements and the Politics of Risk Reduction Q

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 47 (2014) 278–289 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/shpsc Making birth defects ‘preventable’: Pre-conceptional vitamin supplements and the politics of risk reduction q Salim Al-Gailani Department of History and Philosophy of Science, University of Cambridge, Free School Lane, Cambridge CB2 3RH, UK article info abstract Article history: Since the mid-1990s, governments and health organizations around the world have adopted policies Available online 21 November 2013 designed to increase women’s intake of the B-vitamin ‘folic acid’ before and during the first weeks of pregnancy. Building on initial clinical research in the United Kingdom, folic acid supplementation has Keywords: been shown to lower the incidence of neural tube defects (NTDs). Recent debate has focused principally Folic acid on the need for mandatory fortification of grain products with this vitamin. This article takes a longer Vitamin supplements view, tracing the transformation of folic acid from a routine prenatal supplement to reduce the risk of Pre-conception anaemia to a routine ‘pre-conceptional’ supplement to ‘prevent’ birth defects. Understood in the 1950s Public health in relation to social problems of poverty and malnutrition, NTDs were by the end of the century more Clinical trials Risk likely to be attributed to individual failings. This transition was closely associated with a second. Folic acid supplements were initially prescribed to ‘high-risk’ women who had previously borne a child with a NTD. -

HIV) on Human Immune Cells

DUNCAN, BRYCE, Ph. D. Studies Examining the Infectivity of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) on Human Immune Cells. (2017) Directed by Dr. Christopher L. Kepley. 63 pages. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) establishes a latent infection in cells to ensure a persistent infection throughout an infected individual’s life. HIV can establish this latent infection in a variety of cells. Highly Active Anti-Retroviral Treatment (HAART) is a selection of drugs used to inhibit the production of new HIV and new infections and can effectively diminish virus population in blood. However, due to the pathological mechanism of the virus, it is not possible yet to completely eradicate virus as it remains immunologically invisible in latent cellular reservoirs. The cellular reservoirs where HIV evades the immune system are not known completely. Current research efforts are focused on identifying the cellular populations where HIV remains latent and determine how those latent reservoirs are established. By identifying latent cellular reservoirs where HIV resides strategies can be developed to target and kill infected cells or prevent emergence of virus. We hypothesized that primary, skin, human mast cells may represent a previously unknown latent reservoir for HIV. Because mast cells can be activated through IgE-and non-IgE-dependent stimulation, we further hypothesized activated mast cells may be more vulnerable to infection. Our experimentations suggest that skin-derived mast cells are not susceptible to HIV infection and are not an inducible reservoir for HIV. One strategy for inhibiting viral replication has been with fullerenes. Fullerenes are carbon spheres that can be functionalized for use in various biological systems. -

House of Lords Official Report

Vol. 811 Monday No. 221 26 April 2021 PARLIAMENTARYDEBATES (HANSARD) HOUSE OF LORDS OFFICIAL REPORT ORDEROFBUSINESS Death of a Member: Baroness O’Cathain........................................................................2061 Retirement of a Member: Lord Denham .........................................................................2061 Questions Industrial Strategy: Local Growth................................................................................2062 Folic Acid .....................................................................................................................2065 Natural Habitats: Infrastructure Projects .....................................................................2069 Creative Industries: Covid-19 .......................................................................................2073 Commonwealth War Graves Commission: Historical Inequalities Report Statement......................................................................................................................2076 Public Health (Coronavirus) (Protection from Eviction) (England) (No. 2) (Amendment) Regulations 2021 Civil Proceedings Fees (Amendment) Order 2021 Motions to Approve.......................................................................................................2087 Single Use Carrier Bags Charges (England) (Amendment) Order 2021 Motion to Approve ........................................................................................................2087 British Library Board (Power to Borrow) Bill Third Reading