The Perishing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1Monologues' Conclude on Campus Farley Refurbishing Begins

r----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------~ THE The Independent Newspaper Serving Notre Dame and Saint Mary's VOLUME 40: ISSUE 89 THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 16.2006 NDSMCOBSERVER.COM 1Monologues' conclude on campus STUDENT SENATE Leaders Jenkins' attendance, broad panel discussion cap off third and final night of perfomances push wage "I went to listnn and learn, and By KAITLYNN RIELY I did that tonight and I thank the • Nrw.,Writ<·r east," Jenkins said af'tnr the play. .Jenkins, who dedinml further calllpaign Tlw third and final production comment on the "Monologues" of "Tiw Vagina Monologues" at Wednesday, had mandated the By MADDIE HANNA Notrn Damn this y11ar was play be pnrformed in the aca Associate News Editor marknd by thn attnndancn of demic setting of DeBartolo Hall Univnrsily Prnsid1n1l Father .John this year, without the l"undraising .Jnnkins and a wide-ranging ticket sales of' years past. Junior After loaders of the Campus parwl discussion on snxual vio Madison Liddy, director of this Labor Aetion Projoct (CLAP) lnHrn, Catholic. teaching and ynar's "Monologues." and later delivered a eornprnhnnsivo ollwr lopks Wednesday night. the panelists thanked Jenkins for presentation on the group's .11~11kins saw the play per his prnsenen at the performance . living wage campaign to l"orrm~d for tho f"irst time During tho panel diseussion fol Student Senate Wednesday, W1Hfrwsday, just ovnr three lowing thn play, panelists senators responded by unani w1wks after hP initialed a applauded the efforts of the pro mously passing two rolated Univnrsity-widn discussion about duction toward eliminating vio resolutions - one basod on acadnmk l"mmlom and Catholic lence against women and policy, tho other on ideology. -

Willie Nelson

LESSON GUIDE • GRADES 3-6 TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 Introduction 4 About the Guide 5 Pre and Post-Lesson: Anticipation Guide 6 Lesson 1: Introduction to Outlaws 7 Lesson 1: Worksheet 8 Lyric Sheet: Me and Paul 9 Lesson 2: Who Were The Outlaws? 10 Lesson 3: Worksheet 12 Activities: Jigsaw Texts 14 Lyric Sheet: Are You Sure Hank Done It This Way 15 Lesson 4: T for Texas, T for Tennessee 16 Lesson 5: Literary Lyrics 17 Lyric Sheet: Daddy What If? 18 Lyric Sheet: Act Naturally 19 Complete Tennessee Standards 21 Complete Texas Standards 23 Biographies 3-6 Table of Contents 2 Outlaws and Armadillos: Country’s Roaring ‘70s examines how the Outlaw movement greatly enlarged country music’s audience during the 1970s. Led by pacesetters such as Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, Kris Kristofferson, and Bobby Bare, artists in Nashville and Austin demanded the creative freedom to make their own country music, different from the pop-oriented sound that prevailed at the time. This exhibition also examines the cultures of Nashville and fiercely independent Austin, and the complicated, surprising relationships between the two. Artwork by Sam Yeates, Rising from the Ashes, Willie Takes Flight for Austin (2017) 3-6 Introduction 3 This interdisciplinary lesson guide allows classrooms to explore the exhibition Outlaws and Armadillos: Country’s Roaring ‘70s on view at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum® from May 25, 2018 – February 14, 2021. Students will examine the causes and effects of the Outlaw movement through analysis of art, music, video, and nonfiction texts. In doing so, students will gain an understanding of the culture of this movement; who and what influenced it; and how these changes diversified country music’s audience during this time. -

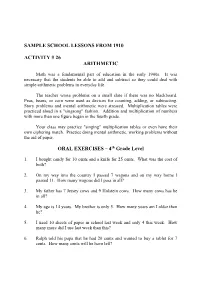

Sample School Lessons from 1910 Activity # 26 Arithmetic

SAMPLE SCHOOL LESSONS FROM 1910 ACTIVITY # 26 ARITHMETIC Math was a fundamental part of education in the early 1900s. It was necessary that the students be able to add and subtract so they could deal with simple arithmetic problems in everyday life. The teacher wrote problems on a small slate if there was no blackboard. Peas, beans, or corn were used as devices for counting, adding, or subtracting. Story problems and mental arithmetic were stressed. Multiplication tables were practiced aloud in a "singsong" fashion. Addition and multiplication of numbers with more than one figure began in the fourth grade. Your class may practice "singing" multiplication tables or even have their own ciphering match. Practice doing mental arithmetic, working problems without the aid of paper. ORAL EXERCISES – 4th Grade Level 1. I bought candy for 10 cents and a knife for 25 cents. What was the cost of both? 2. On my way into the country I passed 7 wagons and on my way home I passed 11. How many wagons did I pass in all? 3. My father has 7 Jersey cows and 9 Holstein cows. How many cows has he in all? 4. My age is 14 years. My brother is only 5. How many years am I older then he? 5. I used 10 sheets of paper in school last week and only 4 this week. How many more did I use last week than this? 6. Ralph told his papa that he had 20 cents and wanted to buy a tablet for 7 cents. How many cents will he have left? 7. -

Coaster Brook Trout: the History & Future Artist Profile: Ted Hansen Swinging for Steelhead

Trout Unlimited MINNESOTAThe Official Publication of Minnesota Trout Unlimited - February 2019 March 15th-17th, 2019 l Tickets on Sale Now! without written permission of Minnesota Trout Unlimited. Trout Minnesota of permission written without Copyright 2019 Minnesota Trout Unlimited - No portion of this publication may be reproduced reproduced be may publication this of portion No - Unlimited Trout Minnesota 2019 Copyright Shore Fishing Lake Superior Coaster Brook Trout: The History & Future Artist Profile: Ted Hansen Swinging for Steelhead MNTU Year in Review ROCHESTER, MN ROCHESTER, PERMIT NO. 281 NO. PERMIT Chanhassen, MN 55317-0845 MN Chanhassen, PAID P.O. Box 845 Box P.O. Tying the CDC & Elk U.S. POSTAGE POSTAGE U.S. Minnesota Trout Unlimited Trout Minnesota Non-Profit Org. Non-Profit Trout Unlimited Minnesota Council Update MINNESOTA The Voice of MNTU Meet You at the Expo! By Steve Carlton, Minnesota Council Chair On The Cover appy 2019! May the new year program. The program had a very im- bring more fish and more fishing pressive first half of the school year. Fish A coaster brook trout from Lake Su- Hopportunities…in more fishy tanks in schools around the state are now perior is ready to be released. Learn places! Since our last newsletter, I have filled with young trout growing toward about coaster brook trout, their chal- not had the time to get out, so all I can do release in the spring. Our education lenges, and current work on their be- is look forward to my next opportunity. program can always use your help and half on page 4. -

5713 Theme Ideas

5713 THEME IDEAS & 1573 Bulldogs, no two are the same & counting 2B part of something > U & more 2 can play that game & then... 2 good 2 b 4 gotten ? 2 good 2 forget ! 2 in one + 2 sides, same story * 2 sides to every story “ 20/20 vision # 21 and counting / 21 and older > 21 and playing with a full deck ... 24/7 1 and 2 make 12 25 old, 25 new 1 in a crowd 25 years and still soaring 1+1=2 decades 25 years of magic 10 minutes makes a difference 2010verland 10 reasons why 2013 a week at a time 10 things I Hart 2013 and ticking 10 things we knew 2013 at a time 10 times better 2013 degrees and rising 10 times more 2013 horsepower 10 times the ________ 2013 memories 12 words 2013 pieces 15 seconds of fame 2013 possibilities 17 reasons to be a Warrior 2013 reasons to howl 18 and counting 2013 ways to be a Leopard 18 and older 2 million minutes 100 plus you 20 million thoughts 100 reasons to celebrate 3D 100 years and counting Third time’s a charm 100 years in the making 3 dimensional 100 years of Bulldogs 3 is a crowd 100 years to get it right 3 of a kind 100% Dodger 3 to 1 100% genuine 3’s company 100% natural 30 years of impossible things 101 and only 360° 140 traditions CXL 4 all it’s worth 150 years of tradition 4 all to see (176) days of La Quinta 4 the last time 176 days and counting 4 way stop 180 days, no two are the same 4ming 180 days to leave your mark 40 years of colorful memories 180° The big 4-0 1,000 strong and growing XL (40) 1 Herff Jones 5713 Theme Ideas 404,830 (seconds from start to A close look A little bit more finish) A closer look A little bit of everything (except 5-star A colorful life girls) 5 ways A Comet’s journey A little bit of Sol V (as in five) A common ground A little give and take 5.4.3.2.1. -

View / Open Biebelle Patricia Z Mfa2010sp.Pdf

IF I AM A STRANGER by PATRICIA Z. BIEBELLE A THESIS Presented to the Creative Writing Program and the Graduate School ofthe University ofOregon in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree of Master ofFine Arts June 2010 11 "If! Am a Stranger," a thesis prepared by Patricia Z. Biebelle in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the Master ofFine Arts degree in the Creative Writing Program. This thesis has been approved and accepted by: 20 (0 Date Accepted by: ~~ Dean ofthe Graduate School 111 CURRICULUM VITAE NAME OF AUTHOR: Patricia Z. Biebelle PLACE OF BIRTH: Carlsbad, New Mexico DATE OF BIRTH: November 27,1979 GRADUATE AND UNDERGRADUATE SCHOOLS ATTENDED: University ofOregon, Eugene, Oregon New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, New Mexico DEGREES AWARDED: Master ofFine Arts, Creative Writing, June 2010, University ofOregon Bachelor ofArts, English, May 2008, New Mexico State University PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE: Graduate Teaching Fellow, University ofOregon English Department, 2009-2010 Graduate Teaching Fellow, University ofOregon Creative Writing Program, 2008-2009 GRANTS, AWARDS AND HONORS: English Department Graduate Teaching Fellowship, University ofOregon, 2009 2010 Creative Writing Graduate Teaching Fellowship, University of Oregon, 2008 2009 Penny Wilkes Scholarship in Writing and the Environment, "Obligation," University ofOregon, 2009 IV ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to express sincere appreciation to Associate Professor Laurie Lynn Drummond for her invaluable help with this manuscript. In addition, special thanks are due to Timothy Ahearne, my husband, whose steadfast support made this project possible, and whose love and consideration are the cornerstones ofmy success. I also thank my family for their support, my M.F.A. colleagues for their patience and attention, and the fiction faculty ofthe University ofOregon Creative Writing Program for the knowledge they have shared. -

ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: WHICHEVER of MY

ABSTRACT Title of thesis: WHICHEVER OF MY PARENTS’ GODS WILL TAKE ME Ali Goldstein, Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing: Fiction, 2015 Thesis Directed By: Professor Howard Norman, Master of Fine Arts Program in Creative Writing This novella titled Whichever of My Parents’ Gods will Take Me is about a young woman named Ruth growing up in a bicultural home in post-World War II Detroit, Michigan as she trains for her first marathon. Told from a first-person lyrical point-of- view, the story seeks to capture Ruth’s development as a runner and young woman through her voice and sensory perception. This novella takes the form of a triptych with three discreet sections in Ruth’s life – adolescence, young motherhood, and old age – that cohere the life of a woman while putting Ruth’s myriad voices in dialogue with one another. This is a story about a young woman obsessed with running at a time where it was both strange and dangerous for a young woman to run alone at dawn – but also about bravery, freedom, and what she saw as she ran through a changing and healing city. WHICHEVER OF MY PARENTS’ GODS WILL TAKE ME by Ali Goldstein Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing 2015 Advisory Committee: Professor Howard Norman, Chair Professor Emily Mitchell Professor Maud Casey TABLE OF CONTENTS Part One…………………..1 Part Two…………………..59 Part Three…………………84 ii Part One Daddy brought home the running shoes in a brown paper grocery sack. -

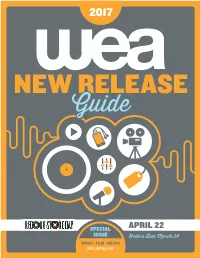

APRIL 22 ISSUE Orders Due March 24 MUSIC • FILM • MERCH Axis.Wmg.Com 4/22/17 RSD AUDIO & VIDEO RECAP

2017 NEW RELEASE SPECIAL APRIL 22 ISSUE Orders Due March 24 MUSIC • FILM • MERCH axis.wmg.com 4/22/17 RSD AUDIO & VIDEO RECAP ARTIST TITLE LBL CNF UPC SEL # SRP ORDERS DUE Le Soleil Est Pres de Moi (12" Single Air Splatter Vinyl)(Record Store Day PRH A 190295857370 559589 14.98 3/24/17 Exclusive) Anni-Frid Frida (Vinyl)(Record Store Day Exclusive) PRL A 190295838744 60247-P 21.98 3/24/17 Wild Season (feat. Florence Banks & Steelz Welch)(Explicit)(Vinyl Single)(Record WB S 054391960221 558713 7.98 3/24/17 Store Day Exclusive) Cracked Actor (Live Los Angeles, Bowie, David PRH A 190295869373 559537 39.98 3/24/17 '74)(3LP)(Record Store Day Exclusive) BOWPROMO (GEM Promo LP)(1LP Vinyl Bowie, David PRH A 190295875329 559540 54.98 3/24/17 Box)(Record Store Day Exclusive) Live at the Agora, 1978. (2LP)(Record Cars, The ECG A 081227940867 559102 29.98 3/24/17 Store Day Exclusive) Live from Los Angeles (Vinyl)(Record Clark, Brandy WB A 093624913894 558896 14.98 3/24/17 Store Day Exclusive) Greatest Hits Acoustic (2LP Picture Cure, The ECG A 081227940812 559251 31.98 3/24/17 Disc)(Record Store Day Exclusive) Greatest Hits (2LP Picture Disc)(Record Cure, The ECG A 081227940805 559252 31.98 3/24/17 Store Day Exclusive) Groove Is In The Heart / What Is Love? Deee-Lite ECG A 081227940980 66622 14.98 3/24/17 (Pink Vinyl)(Record Store Day Exclusive) Coral Fang (Explicit)(Red Vinyl)(Record Distillers, The RRW A 081227941468 48420 21.98 3/24/17 Store Day Exclusive) Live At The Matrix '67 (Vinyl)(Record Doors, The ECG A 081227940881 559094 21.98 3/24/17 -

Dying to Live Forever Sophia Harris Journal 1860 to 1861 Shirley Ilene Davis University of Northern Iowa

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Northern Iowa University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate College 2016 Dying to live forever Sophia Harris journal 1860 to 1861 Shirley Ilene Davis University of Northern Iowa Copyright © 2016 Shirley Ilene Davis Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits oy u Recommended Citation Davis, Shirley Ilene, "Dying to live forever Sophia Harris journal 1860 to 1861" (2016). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 235. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd/235 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 0 Copyright by SHIRLEY ILENE DAVIS 2016 All Rights Reserved 1 DYING TO LIVE FOREVER SOPHIA HARRIS JOURNAL 1860 TO 1861 An Abstract of a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Shirley Ilene Davis University of Northern Iowa May 2016 2 ABSTRACT Sophia Harris’s journal is a window into one woman’s experiences in an area that transformed from a frontier outpost to a market-oriented and increasingly urbanized society. It also sheds light on how she made sense of the meaning of these changes in her personal life: specifically how her religious understandings of death shaped her understanding of the world she lived in. -

Dance Company Presents Spring Concert Surveys, Surveys, Surveys the FSU Dance Company, Under Guest Artist Claire Porter, a the Artistic Direction of Dr

F R OStateLines S T B U R G S T A T E U N I V E R S I T Y wwwfrostburgedu/news/statelineshtm For and about FSU people A publication of the FSU Office of Advancement Volume 35, Number 25, April 4, 2005 Copy deadline: noon Wednesday, 228 Hitchins or emedcalf@frostburg$edu Middle States Dance Company Presents Spring Concert Surveys, Surveys, Surveys The FSU Dance Company, under Guest artist Claire Porter, a the artistic direction of Dr. modern dance performance artist, (To Help Frostburg State!) Barry Fischer, will present its and her company, Portables, are A year from now (April 2-5, 2006), Spring Dance Concert on internationally recognized for FSU will host a team of evaluators Thursday, Friday and Saturday, using theatrical elements and representing the Middle States Commis- April 7, 8 and 9, at 8 p.m. and humor in performances. She sion on Higher Education, our regional Sunday, April 10, at 2 p.m. in will perform two solos. accrediting agency. To prepare for this the PAC Drama Theatre. Dance majors from the visit, the University is conducting a Guest choreographer Dance Composition comprehensive self-study. This month, will be FSU alumna Lori I class will the Self-Study Steering Committee will Cannon, one of the first perform a variety be sending surveys to students, faculty, graduates of FSU’s dance of their own works and staff. We encourage you to take major. She will present two in hip hop and the time in the coming weeks to fill works. The first is a solo modern styles. -

MY BERKSHIRE B Y

MY BERKSHIRE b y Eleanor F . Grose OLA-^cr^- (\"1S MY BERKSHIRE Childhood Recollections written for my children and grandchildren by Eleanor F. Grose POSTSCIPT AND PREFACE Instead of a preface to my story, I am writing a postscript to put at the beginning! In that way I fulfill a feeling that I have, that now that I have finished looking back on my life, I am begin' ning again with you! I want to tell you all what a good and satisfying time I have had writing this long letter to you about my childhood. If it hadn’t been for you, I wouldn’t have had the fun of thinking about and remembering and trying to make clear the personalities of my father and mother and making them integrated persons in some kind of perspective for myself as well as for you—and I have en joyed it all very much. I know that I will have had the most fun out of it, but I don’t begrudge you the little you will get! It has given me a very warm and happy feeling to hear from old friends and relatives who love Berkshire, and to add their pleasant memo ries to mine. But the really deep pleasure I have had is in linking my long- ago childhood, in a kind of a mystic way, in my mind, with you and your future. I feel as if I were going on with you. In spite of looking back so happily to old days, I find, as I think about it, that ever since I met Baba and then came to know, as grown-ups, my three dear splendid children and their children, I have been looking into the future just as happily, if not more so, as, this win ter, I have been looking into the past. -

An Ideal Husband Script

An Ideal Husband Script - Dialogue Transcript Voila! Finally, the An Ideal Husband script is here for all you quotes spouting fans of the movie starring Julianne Moore and Jeremy Northam. This script is a transcript that was painstakingly transcribed using the screenplay and/or viewin gs of An Ideal Husband. I know, I know, I still need to get the cast names in th ere and I'll be eternally tweaking it, so if you have any corrections, feel free to drop me a line. You won't hurt my feelings. Honest. Swing on back to Drew's Script-O-Rama afterwards for more free movie scripts! An Ideal Husband Script - Your usual, my lord. - Mmm? Good morning, my lord. The morning paper, my lord. "Sir Robert Chiltern, a rising star in Parliament,... .. tonight hosts a party that promises to be the highlight of the social calendar... .. with his wife, Lady Gertrude,... .. who is herself a leading figure in women's politics. " "Together this couple... .. represents what is best in English public life... .. and is a noble contrast to the lax morality... .. so common amongst foreign politicians. " Dear oh dear. They will never say that about me, will they, Phipps? I sincerely hope not, sir. Bit of a busy day today, I'm afraid. Distressingly little time for sloth or idleness. - Sorry to hear it, sir. - Not entirely your fault, Phipps. Not this time. Thank you, my lord. - Good morning, Tommy! - Morning, Lady Chiltern. I very much look forward to this evening. - Miss Mabel. - Tommy. I hope you can make our usual appointment..