A Tale of Three Cities: Crime and Displacement After Hurricane Katrina Sean P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Contents

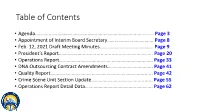

Table of Contents • Agenda………………………………………………………………………….......... Page 3 • Appointment of Interim Board Secretary………………………………. Page 8 • Feb. 12, 2021 Draft Meeting Minutes……………………………………. Page 9 • President’s Report………………................................…………………. Page 20 • Operations Report………………………………………………………………… Page 33 • DNA Outsourcing Contract Amendments………………………….….. Page 41 • Quality Report………………………………………………………………......... Page 42 • Crime Scene Unit Section Update………………………………............ Page 55 • Operations Report Detail Data…………………………………..…………. Page 62 Houston Forensic Science Center, Inc. Board of Directors Virtual Meeting March 12, 2021 Position 1 - Dr. Stacey Mitchell, Board Chair Position 2 - Anna Vasquez Position 3 - Philip Hilder Position 4 - Francisco Medina Position 5 - Janet Blancett Position 6 - Ellen Cohen Position 7 - Lois J. Moore Position 8 - Mary Lentschke, Vice Chair Position 9 - Vicki Huff Ex-Officio - Tracy Calabrese HOUSTON FORENSIC SCIENCE CENTER, INC. NOTICE OF PUBLIC MEETING PUBLIC ACCESS WILL BE VIA TELECONFERENCE ONLY March 12, 2021 In accordance with Texas Governor Greg Abbott’s temporary suspension of certain provisions of the Texas Open Meetings Act, issued March 16, 2020, notice is hereby given that beginning at 9 a.m. on the date set out above, the Board of Directors (the "Board") of the Houston Forensic Science Center, Inc. (the "Corporation,” or “HFSC”) will meet via videoconference (Microsoft Teams.) HFSC is conducting this virtual meeting to advance the public health goal of limiting face-to-face interactions and to slow the spread of the coronavirus (COVID-19.) Gov. Abbott’s temporary suspension of certain open meetings laws was issued in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and in accordance with section 418.016 of the Texas Government Code. Gov. Abbott specifically suspended certain provisions of the law, which required government officials and members of the public to be physically present at a specified meeting location. -

Badgegun-June-2015-Issue.Pdf

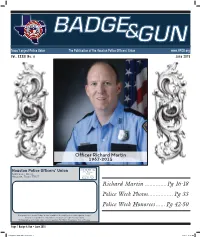

Texas’ Largest Police Union The Publication of the Houston Police Officers’ Union www.HPOU.org Vol. XXXXI No. 6 June 2015 Officer Richard Martin 1967-2015 NON-PROFIT ORG. Houston Police Officers’ Union U.S. Postage 1600 State Street PAID Houston, Texas Houston, Texas 77007 Permit No. 7227 Richard Martin ..............Pg 16-18 Police Week Photos ................ Pg 33 Police Week Honorees ...... Pg 42-50 Non-profit Statement: Badge & Gun is published monthly at no subscription charge. Send Correspondence and Address Changes (include mailing label) To: BADGE & GUN 1600 State Street Houston, TX 77007. Telephone: 713-237-0282. Page 1 Badge & Gun • June 2015 BadgeGun June 2015 Issue.indd 1 6/2/15 1:35 AM HPOU Board of Directors Executive Board Ray Hunt Doug Griffith Joseph Gamaldi Will Reiser President 1st Vice-President 2nd Vice-President Secretary [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Board Members Kawanski Nichols Gary Hicks Jeff Wagner Robert Breiding David Riggs Terry Wolfe Don Egdorf Bubba Caldwell Director 1 Director 2 Director 3 Director 4 Director 5 Director 6 Director 7 Director 8 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Joseph Castaneda Rebecca Dallas Rosalinda Ybanez Timothy Whitaker Luis Menedez-Sierra Robert Sandoval Stephen Augustine Tom Hayes Director 9 Director 10 Director 11 Director 12 Director 13 Director 14 Director 15 Director 16 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] -

Fort Bend County: Life in the Urban Fast Lane

Houston Business A Perspective on the Houston Economy Fort Bend County: Life in the Urban Fast Lane Fort Bend County, 14 miles southwest of the central business district, is the fastest growing part of the Houston metropolitan area. Fort Bend’s spectacular success in recent years has earned it a long and growing list of accolades: Woods and Poole, an economic consulting group, listed it as having the 10th strongest economic base of any Location and U.S. county; American Demographics Inc. named timing have worked it the nation’s third-best address for managerial for Fort Bend. Large and professional workers; Texas Business named its Sugar Land community the second-best city in tracts of land located Texas for corporate expansion or relocation. Cen- FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF DALLAS HOUSTON BRANCH December 1996 close to the inner city sus data show that among counties with 250,000 or more residents, Fort Bend enjoyed the second- give it important fastest population growth of any U.S. county advantages over other through the first half of the 1990s, trailing only Houston suburbs. Clark County in the Las Vegas, Nevada, area. What’s the formula for this kind of growth? Fort Bend’s companions on these high-performance lists are mostly suburban counties across the United States, including cities such as Washington, D.C., Atlanta and Memphis. High-growth Texas counties include Williamson (Round Rock and Georgetown near Austin) and the more mature Collin County (Plano and North Dallas). Fort Bend might be dismissed as just another emerging suburb, except that its level of success sets it apart. -

Bail, Crime & Public Safety

David Mitcham Harris County District Attorney’s Office First Assistant/Chief of Courts 500 Jefferson Street, Suite 600 Houston, TX 77002 Vivian King First Assistant/Chief of Staff HARRIS COUNTY DISTRICT ATTORNEY KIM OGG Bail, Crime & Public Safety A report by the Harris County District Attorney’s Office to the Harris County Commissioners Court September 2, 2021 David Mitcham Harris County District Attorney’s Office First Assistant/Chief of Courts 500 Jefferson Street, Suite 600 Houston, TX 77002 Vivian King First Assistant/Chief of Staff HARRIS COUNTY DISTRICT ATTORNEY KIM OGG September 2, 2021 Honorable Harris County Judge Lina Hidalgo Honorable Rodney Ellis, Harris County Commissioner Pct. 1 Honorable Adrian Garcia, Harris County Commissioner Pct. 2 Honorable Tom Ramsey, Harris County Commissioner Pct. 3 Honorable Jack Cagle, Harris County Commissioner Pct. 4 1001 Preston Street, Suite 938 Houston, Texas 77002 Dear Judge Hidalgo and Harris County Commissioners, Enclosed please find a report from the Harris County District Attorney's Office, “Bail, Crime & Public Safety.” Our intent in gathering, analyzing, and reporting our findings, is to provide county leadership and the public at large with a thorough, transparent assessment of the impact of current bail decisions by the courts on public safety. Commissioners have all previously received reports from the O'Donnell bail monitors in September 2020 and March 2021, as well as a memorandum from the Harris County Justice Administration Department, in February, 2021. Because these previous reports reflect results which conflict with the daily experiences of prosecutors, police, and crime victims, the District Attorney's Office took another look at the same information and data used by the previous analysts, and produced the attached report. -

Should We Police Disorder? a Local Level Examination of the Spatial

SHOULD WE POLICE DISORDER? A LOCAL LEVEL EXAMINATION OF THE SPATIAL AND TEMPORAL ASPECTS OF THE BROKEN WINDOWS THEORY _____________ A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Criminal Justice and Criminology Sam Houston State University _____________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _____________ by Di Jia May, 2018 SHOULD WE POLICE DISORDER? A LOCAL LEVEL EXAMINATION OF THE SPATIAL AND TEMPORAL ASPECTS OF THE BROKEN WINDOWS THEORY by Di Jia ______________ APPROVED: Larry T. Hoover, PhD Dissertation Director Jurg Gerber, PhD Committee Member Yan Zhang, PhD Committee Member Philip Lyons, PhD Dean, College of Criminal Justice DEDICATION I would like to dedicate this dissertation to my deceased grandmother Shihui Shen and my uncle Wei Hao, who always had high hopes for me and fully supported me. I miss them so much. I will remember them forever. In addition, I also dedicate this study to my mother Ming Hao, my husband Weining Che, and my friend Dr. David Webb. They all brought love and lights to my life. Without their help and support during my hard time, this dissertation would have been impossible to complete. Thank you and I love you. iii ABSTRACT Jia, Di, Should we police disorder? A local level examination of the spatial and temporal aspects of the Broken Windows Theory. Doctor of Philosophy (Criminal Justince), May, 2018, Sam Houston State University, Huntsville, Texas. In 1982, Wilson and Kelling introduced the Broken Windows theory (BWT) arguing that policing neighborhood disorder would reduce serious crime while enhancing the quality of life in neighborhoods. -

Plenary Papers of the 1998 Conference on Criminal Justice Research and Evaluation

T O EN F J TM U R ST A I U.S. Department of Justice P C E E D B O J C S F A V M Office of Justice Programs F O I N A C I J S R E BJ G O OJJ DP O F PR National Institute of Justice JUSTICE Viewing Crime and Justice From a Collaborative Perspective: Plenary Papers of the 1998 Conference on Criminal Justice Research and Evaluation Research Forum Cosponsored by Office of Justice Programs Bureau of Justice Assistance Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs 810 Seventh Street N.W. Washington, DC 20531 Janet Reno Attorney General Raymond C. Fisher Associate Attorney General Laurie Robinson Assistant Attorney General Noël Brennan Deputy Assistant Attorney General Jeremy Travis Director, National Institute of Justice Department of Justice Response Center 800–421–6770 Office of Justice Programs National Institute of Justice World Wide Web Site World Wide Web Site http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/nij National Institute of Justice Viewing Crime and Justice From a Collaborative Perspective: Plenary Papers of the 1998 Conference on Criminal Justice Research and Evaluation David Kennedy J. Phillip Thompson Lisbeth B. Schorr Jeffrey L. Edleson and Andrea L. Bible Cosponsored by the Office of Justice Programs, the National Institute of Justice, the Bureau of Justice Assistance, and the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention July 1999 NCJ 176979 Jeremy Travis Director John Thomas Program Monitor The Professional Conference Series of the National Institute of Justice supports a variety of live researcher-practitioner exchanges, such as conferences, workshops, and planning and development meetings, and provides similar support to the criminal justice field. -

HOUSTON POLICE DEPARTMENT Charles A

HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HPD HOUSTON POLICEDEPARTMENT Larry J.Yium, DeputyDirector Charles A.McClelland,Jr. OFFICE OF PLANNING OFFICE Annise D.Parker Chief ofPolice January 2014 Prepared by: Mayor Houston Police Department Mayor and City Council Member Orientation Presentation The Houston Police Department is proud to present this Command Overview, which is a comprehensive orientation guide that aims to introduce you to the department’s various operations, commands, and divisions, to include sections and units within each. -

The State of Health in Houston/Harris County

THE STATE OF HEALTH HOUSTON/HARRIS COUNTY TEXAS 2009 THE STATE OF HEALTH IN HOUSTON/HARRIS COUNTY 2009 Photos are courtesy of the U.S. Census Bureau The State of Health in Houston/Harris County 2009 Welcome to the State of Health in Houston/Harris County. We are pleased to provide our many constituencies this broad assessment of the health of our community. Many organizations have joined together to determine the most pertinent health indicators, and gathered and organized these measures into a format that we hope will be both interesting and informative. This report provides: • current measures available to evaluate the health in our com- munity • trends in key health measures to allow readers to evaluate changes in local health status and compare these measures to national goals • resources for priority setting in preventing disease, promoting health and improving access to care • health care information and websites for more detailed infor- mation • summaries of key public health actions to address the identi- fied issues Please feel free to use this information as needed for planning and decision making. We hope this report assists you in your efforts to address health-related concerns in our community. Patricia G. Bray, Ph.D. Executive Director St. Luke’s Episcopal Health Charities, Inc. Acknowledgments In 2005, Stephen L. Williams, Director, Houston Department of Health and Human Services (HDHHS), and Herminia Palacio, Executive Director, Harris County Public Health and Envi- ronmental Services (HCPHES), created a joint State of Health annual report. In 2006, that document expanded to include three more public health groups, the Harris County Healthcare Alliance (HCHA), the Mental Health and Mental Retardation Authority of Harris County (MHMRA), and the Harris County Hospital District (HCHD). -

Welcoming-Houston-Task-Force-Recommendations FINAL 01-18-17.Pdf

ii 0 “When I ran for Mayor, you often heard me say that I wanted Houston to be a city with no limits, which acted responsibly, where government works for the people and is held to a higher standard – a city of hope, opportunity, and inspiration. That is the city I, along with your help, hope to continue to build. Houston is a city of immigrants and refugees, and they have a long and deep-rooted history in making Houston the great city it is today. As the nation’s fourth largest city, and most diverse metropolitan area in America, Houston is home to people from all over the world. One in four Houstonians is foreign-born, over 140 languages are spoken in our neighborhoods, and 90 countries are officially represented in the consular corps. This plan will help us develop best practices on how to better integrate and assist newly arrived Houstonians into our city. Immigrants and refugees are our neighbors. They are the families at our schools, churches, temples and mosques. They contribute to Houston’s vibrant economy, running many small businesses and working in all of Houston’s diverse industries. Regardless of where you come from, what you look like, your disability, what you believe, or who you love, we stand together as Houstonians. Houston always has been and always will be a Welcoming City.” – Mayor Sylvester Turner, December 12, 2016 1 Executive Summary Welcoming Houston is an initiative based on the belief that immigrant communities and receiving communities share many common goals and priorities and, by working together, can forge a stronger, richer democracy. -

The Spatial-Temporal Prediction of Various Crime Types in Houston, TX Based on Hot-Spot Techniques" (2014)

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2014 The ps atial-temporal prediction of various crime types in Houston, TX based on hot-spot techniques Shuzhan Fan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Fan, Shuzhan, "The spatial-temporal prediction of various crime types in Houston, TX based on hot-spot techniques" (2014). LSU Master's Theses. 219. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/219 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SPATIAL-TEMPORAL PREDICTION OF VARIOUS CRIME TYPES IN HOUSTON, TX BASED ON HOT-SPOT TECHNIQUES A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Science in The Department of Geography and Anthropology by Shuzhan Fan B.E., Central South University, 2012 August 2014 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to present my appreciation to my major advisor, Dr. Michael Leitner, who enlightened and guided me during my master’s study and this thesis research. My thesis would not have been achieved and completed without his aid and guidance. Also, I would like to thank Dr. Fahui Wang, Dr. Xuelian Meng and Dr. -

Event Organizers Do NOT Endorse Any Candidate for Public Office

Event organizers do NOT endorse any candidate for public office. Candidates answers are presented as submitted with the exception of contact information corrections. Event organizers wish to thank the candidates who participated in the survey. CANDIDATES Table of Contents: Sallie Alcorn Sallie Alcorn …………… 3 Bill Baldwin Bill Baldwin …………… 7 Jamaal BooneJamaal Boone …………… 10 Willie Davis Willie Davis…………… 11 Eric Dick Eric Dick…………… 12 Michael GriffinMichael Griffin…………… 13 Nick HellyearNick Hellyear …………… 14 James JoeJames Joseph Joe Joseph …………… 16 Michael KuboshMichael Kubosh…………… 20 ErickaEricka McCrutcheon McCrutcheon…………… 21 Marvin McNeeseMarvin McNeese…………… 22 Letitia PlummerLetitia Plummer…………… 23 Sonia Rivera Sonia Rivera…………… 24 David RobinsonDavid Robinson…………… 26 Raj Salhotra Raj Salhotra…………… 26 footnotes 1 By 2030, the population of Houston is expected to grow from 2.2 to 2.8 million people, an increase of 600,000 people. 2 Management Districts (MDs) Tax Increment ReInvestment Zones (TIRZs) 3Community advocates such as: Super Neighborhood Councils, civic organizations, homeowner associations, etc. 4 Houston has a restriction on property taxes (“revenue cap”). 2 Sallie Alcorn - AtLarge 5 salliealcorn.com 281-939-7444 [email protected] less congestion, and well-maintained, safer streets. Third, we P.O. Box 27510, Houston, TX 77227 need city policies and practices to attract the next generation of Houstonians—less sprawl and more vibrant, pedestrian-friendly Education and Experience? activity centers with access to housing, jobs, transportation, Bachelor of Business Administration in Finance from UT - services, parks, retail and recreation. Houston must be a modern Austin. Master of Arts in Public Administration from UH. city that innovates and evolves. I’ve spent over 15 years working learning the workings of city government - in the city’s housing and community development I’m running to make sure city government delivers basic services department, as a district director for a Houston-based congressman, in the smartest way possible. -

Proposed Operational Staffing Enhancements for the Houston Police Department

Proposed Operational Staffing Enhancements for the Houston Police Department The mission of the Houston Police Department is to enhance the quality of life in the city of Houston by working cooperatively with the public to prevent crime, enforce the law, preserve the peace, and provide a safe environment. Charles A. McClelland, Jr. Chief of Police Houston Police Department October 2014 Acknowledgments This report is the culmination of considerable time and effort put forth by several entities within the Houston Police Department. Several sessions with the Senior Executive Staff and the Executive Staff were conducted to solicit input about implications associated with the results of the PERF / Justex Operational Staffing Report. Statistical data was gleaned and verified from several Captains and their respective staffs to illustrate the effort put forth in providing services within our great city. Gratitude is also extended to Mr. David Morgan, Deputy Director, Technology Services, Mr. Larry Yium, Deputy Director, Planning, and Mr. Joseph Fenninger, Deputy Director, Budget and Finance for their contribution in providing input into sections of this report regarding technology, civilianization, and cost implications. Appreciation is also in order for Executive Assistant Chief T. N. Oettmeier for his assistance in preparing this report. Table of Contents Table of Contents Topic Page List of Tables . ii List of Figures. v Executive Summary . 1 Purpose of Report. 3 Section One: Guiding Axioms for Decision‐Making. 6 Section Two: The Challenge of Providing Police Services in Houston . 9 Section Three: The Relationship between Technology and Staffing . .. 48 Section Four: The Relationship between Management and Staffing . 55 Section Five: Staffing Needs for the Houston Police Department.