HUGO WOLF the Complete Songs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Volume One of the Frederick Delius

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Volume One of the Frederick Delius Songbook to be Released in the United States this September ASHFORD, CONNECTICUT (August 22, 2011) – In honor of the 150th anniversary of the birth of the great English composer Frederick Delius (1862-1934), The Complete Delius Songbook – Volume 1 will be released as a CD in the U.S. on September 13, 2011. This is the first volume in a two-volume series that will comprise the first-ever complete recording of all 61 surviving songs of Frederick Delius for voice and piano. This recording features baritone Mark Stone accompanied by Stephen Barlow on piano. Michael Maglaras of 217 Records is Executive Producer. Produced and released first in the United Kingdom on July 18, 2011 on the Stone Records label, and produced in association with 217 Records, this eventual two-volume journey through the Delius songbook will be a delight to listeners everywhere. Pictured: Stephen Barlow and Mark Stone. “We at 217 Records cannot imagine a finer exponent of the English art song than baritone Mark Stone. That he possesses a superb instrument is clear to everyone who knows his work. But he is also a singer of rare intelligence and refinement, and this recording bears his unmistakable stamp,” said Michael Maglaras. “Stephen Barlow is the logical successor to Gerald Moore. He is a great English pianist who brings not only gracious support to this undertaking, but helps create, in every song, an immediate sense of both the drama and the deeper meaning of Delius’s work.” Volume 1, which includes first-time recordings of five of these songs, features all of Delius’s songs to English and Norwegian texts, the latter being sung in English translation. -

Now We Are 126! Highlights of Our 3 125Th Anniversary

Issue 5 School logo Sept 2006 Inside this issue: Recent Visits 2 Now We Are 126! Highlights of our 3 125th Anniversary Alumni profiles 4 School News 6 Recent News of 8 Former Students Messages from 9 Alumni Noticeboard 10 Fundraising 11 A lot can happen in 12 just one year In Memoriam 14 Forthcoming 16 Performances Kim Begley, Deborah Hawksley, Robert Hayward, Gweneth-Ann Jeffers, Ian Kennedy, Celeste Lazarenko, Louise Mott, Anne-Marie Owens, Rudolf Piernay, Sarah Redgwick, Tim Robinson, Victoria Simmons, Mark Stone, David Stout, Adrian Thompson and Julie Unwin (in alphabetical order) performing Serenade to Music by Ralph Vaughan Williams at the Guildhall on Founders’ Day, 27 September 2005 Since its founding in 1880, the Guildhall School has stood as a vibrant showcase for the City of London's commitment to education and the arts. To celebrate the School's 125th anniversary, an ambitious programme spanning 18 months of activity began in January 2005. British premières, international tours, special exhibits, key conferences, unique events and new publications have all played a part in the celebrations. The anniversary year has also seen a range of new and exciting partnerships, lectures and masterclasses, and several gala events have been hosted, featuring some of the Guildhall School's illustrious alumni. For details of the other highlights of the year, turn to page 3 Priority booking for members of the Guildhall Circle Members of the Guildhall Circle are able to book tickets, by post, prior to their going on sale to the public. Below are the priority booking dates for the Autumn productions (see back cover for further show information). -

2017 Season 2

1 2017 SEASON 2 Eugene Onegin, 2016 Absolutely everything was perfection. You have a winning formula Audience member, 2016 1 2 SEMELE George Frideric Handel LE NOZZE DI FIGARO Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart PELLÉAS ET MÉLISANDE Claude Debussy IL TURCO IN ITALIA Gioachino Rossini SILVER BIRCH Roxanna Panufnik Idomeneo, 2016 Garsington OPERA at WORMSLEY 3 2017 promises to be a groundbreaking season in the 28 year history of Cohen, making his Garsington debut, and directed by Annilese Miskimmon, Garsington Opera. Artistic Director of Norwegian National Opera, who we welcome back nine years after her Il re pastore at Garsington Manor. We will be expanding to four opera productions for the very first time and we will now have two resident orchestras as the Philharmonia Orchestra joins us for Our fourth production will be a revival from 2011 of Rossini’s popular comedy, Pelléas et Mélisande. Il turco in Italia. We are delighted to welcome back David Parry, who brings his conducting expertise to his 13th production for us, and director Martin Duncan Our own highly praised Garsington Opera Orchestra will not only perform Le who returns for his 6th season. nozze di Figaro, Il turco in Italia and Semele, but will also perform the world premiere of Roxanna Panufnik’s Silver Birch at the conclusion of the season. To cap the season off we are very proud to present a brand new work commissioned by Garsington from composer Roxanna Panufnik, to be directed Pelléas et Mélisande, Debussy’s only opera and one of the seminal works by our Creative Director of Learning & Participation, Karen Gillingham, and I of the 20th century, will be conducted by Jac van Steen, who brought such will conduct. -

REHEARSAL and CONCERT

Boston Symphony Orchestra* SYMPHONY HALL, BOSTON, HUNTINGTON AND MASSACHUSETTS AVENUES. (Telephone, 1492 Back Bay.) TWENTY-FOURTH SEASON, I 904-1905. WILHELM GERICKE, CONDUCTOR {programme OF THE FIFTH REHEARSAL and CONCERT VITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE. FRIDAY AFTERNOON, NOVEMBER J8, AT 2.30 O'CLOCK. SATURDAY EVENING, NOVEMBER J9, AT 8.00 O'CLOCK. Published by C'A. ELLIS, Manager. 265 CONCERNING THE "QUARTER (%) GRAND" Its Tone Quality is superior to that of an Upright. It occupies practically no more space than an Upright. It costs no more than the large Upright. It weighs less than the larger Uprights. It is a more artistic piece of furniture than an Upright. It has all the desirable qualities of the larger Grand Pianos. It can be moved through stairways and spaces smaller than will admit even the small Uprights. RETAIL WARE ROOMS 791 TREMONT STREET BOSTON Established 1823 : TWENTY-FOURTH SEASON, J904-J905. Fifth Rehearsal and Concert* FRIDAY AFTERNOON, NOVEMBER J8, at 2.30 o'clock- SATURDAY EVENING, NOVEMBER t% at 8.00 o'clock. PROGRAMME. Brahms ..... Symphony No. 3, in F major, Op. go I. Allegro con brio. II. Andante. III. Poco allegretto. IV. Allegro. " " " Mozart . Recitative, How Susanna delays ! and Aria, Flown " forever," from " The Marriage of Figaro Wolf . Symphonic Poem, " Penthesilea," after the like-named' tragedy of Heinrich von Kleist (First time.) " Wagner ..... Finale of " The Dusk of the Gods SOLOIST Mme. JOHANNA GADSKI. There will be an intermission of ten minutes after the Mozart selection. SPECIAL ANNOUNCEMENT. By general desire the concert announced for Saturday evening, Decem- ber 24, '* Christmas Eve," will be given on Thursday evening, December 2a. -

Robert Schumann and the German Revolution of 1848,” for “Music and Revolution,” Concert and Lecture Series

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons History: Faculty Publications and Other Works Faculty Publications 5-2-1998 “Robert Schumann and the German Revolution of 1848,” for “Music and Revolution,” concert and lecture series David B. Dennis Loyola University Chicago, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/history_facpubs Part of the History Commons Author Manuscript This is a pre-publication author manuscript of the final, published article. Recommended Citation Dennis, David B.. “Robert Schumann and the German Revolution of 1848,” for “Music and Revolution,” concert and lecture series. The American Bach Project and supported by the Wisconsin Humanities Council as part of the State of Wisconsin Sesquicentennial Observances, All Saints Cathedral, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, , : , 1998. Retrieved from Loyola eCommons, History: Faculty Publications and Other Works, This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History: Faculty Publications and Other Works by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. © David B. Dennis 1998 “Robert Schumann and the German Revolution of 1848” David B. Dennis Paper for “Music and Revolution,” concert and lecture series arranged by The American Bach Project and supported by the Wisconsin Humanities Council as part of the State of Wisconsin Sesquicentennial Observances, All Saints Cathedral Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 2 May 1998. 1 Let me open by thanking Alexander Platt and Joan Parsley of Ensemble Musical Offering, for inviting me to speak with you tonight. -

Sir Colin Davis Anthology Volume 1

London Symphony Orchestra LSO Live Sir Colin Davis Anthology Volume 1 Sir Colin Davis conductor Colin Lee tenor London Symphony Chorus London Symphony Orchestra Hector Berlioz (1803–1869) – Symphonie fantastique, Op 14 (1830–32) Recorded live 27 & 28 September 2000, at the Barbican, London. 1 Rêveries – Passions (Daydreams – Passions) 15’51’’ Largo – Allegro agitato e appassionato assai – Religiosamente 2 Un bal (A ball) 6’36’’ Valse. Allegro non troppo 3 Scène aux champs (Scene in the fields) 17’16’’ Adagio 4 Marche au supplice (March to the Scaffold) 7’02’’ Allegretto non troppo 5 Songe d’une nuit de sabbat (Dream of the Witches’ Sabbath) 10’31’’ Larghetto – Allegro 6 Hector Berlioz (1803–1869) – Overture: Béatrice et Bénédict, Op 27 (1862) 8’14’’ Recorded live 6 & 8 June 2000, at the Barbican, London. 7 Hector Berlioz (1803–1869) – Overture: Les francs-juges, Op 3 (1826) 12’41’’ Recorded live 27 & 28 September 2006, at the Barbican, London. Hector Berlioz (1803–1869) – Te Deum, Op 22 (1849) Recorded live 22 & 23 February 2009, at the Barbican, London. 8 i. Te Deum (Hymne) 7’23’’ 9 ii. Tibi omnes (Hymne) 9’57’’ 10 iii. Dignare (Prière) 8’04’’ 11 iv. Christe, Rex gloriae (Hymne) 5’34’’ 12 v. Te ergo quaesumus (Prière) 7’15’’ 13 vi. Judex crederis (Hymne et prière) 10’20’’ 2 Antonín Dvořák (1841–1904) – Symphony No 9 in E minor, Op 95, ‘From the New World’ (1893) Recorded live 29 & 30 September 1999, at the Barbican, London. 14 i. Adagio – Allegro molto 12’08’’ 15 ii. Largo 12’55’’ 16 iii. -

Download Booklet

MAG IC L A N T Sophie Daneman ~ soprano Beth Higham-Edwards ~ vibraphone E D Alisdair Hogarth ~ piano Anna Huntley ~ mezzo-soprano R A George Jackson ~ conductor Sholto Kynoch ~ piano O N Anna Menzies ~ cello Edward Nieland ~ treble H Sinéad O’Kelly ~ mezzo-soprano Natalie Raybould ~ soprano - T S E Collin Shay ~ countertenor Philip Smith ~ baritone Nicky Spence ~ tenor A Mark Stone ~ baritone Verity Wingate ~ soprano C L N A E R S F L Y R E H C Y B S G N O S FOREWORD Although the thought of singing and acting in front of an audience terrifies me, there is nothing I enjoy more than being alone at my piano and desk, the notes on an empty page yet to be fixed. Fortunately I am rarely overheard as I endlessly repeat words and phrases, trying to find the music in them: the exact pitches and rhythms needed to portray a particular emotion often take me an exasperatingly long time to find. One of the things that I love most about writing songs is that I feel I truly get to know and understand the poetry I am setting. The music, as I write it, allows me to feel as if I am inhabiting the character in the poem, and I often only discover what the poem really says to me when I reach the final bar. This disc features a number of texts either written especially for me (Kei Miller, Tamsin Collison, Andrew Motion, Stuart Murray), or already in existence (Kate Wakeling, Ian McMillan, 4th century Aristotle). -

Nikolaus Lenau's "Faust" : Ein Gedicht

1918 NIKOLAUS LENAU'S "FAUST" Ein Gedicht BY ANTOINE FERDINAND ERNST HENRY MEYER THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS IN GERMAN COLLEGE OF LIBERAL ARTS AND SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS 19 18 ms 15* ft 5 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS L^......i 9 il c3 THIS IS TO CERTIFY THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY £j£rtdt£k^ $^Zf.& ENTITLED (^^*ditL4. i%. £&Z. A^rrtf. ^.t^kit^. ^^....^^^.^(^.. IS APPROVED BY ME AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF wiÄrfifdt^ Instructor in Charge Approved : HEAD OF DEPARTMENT OF titäkttt**^ 410791 ÜlUC Inhaltsübersicht. Seite A. Einführung. i _ üi B. Biographischer Abriss. I. Lenaus Jugend in Österreich-Ungarn bis zum Jahre 1831. 1-20 II. Wander jähre vom Juni 1831 bis September 1833. a. In Schwaben 21 - 29 b. Amerika-Reise und Aufenthalt 30 - 35 III. Faust Periode. 36 - 56 (Oktober 1833 bis März 1836) C. Schluss. 57 - 62 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/nikolauslenausfaOOmeye 1 Nikolaus Lenau's "Faust" . Ein Ge dicht. A. Einführung. ^nter den vielen Bearbeitern der Faustsage nimmt Nikolaus Lenau einen hervorragenden Platz ein. Von den nachgoetheschen Dich Lungen ist seine Bearbeitung unzweifelhaft die gediegenste. Sie ist eine "Neu- und weiterdi chtung des Faustproblems, eine neue dichterische Auffassung und Durchführung des Faustoff es. Um seine originelle Lebens Anschauung in Torte zu kleiden, wählte Lenau sich Faust "den Philosophen der Philosophen", wie sich dieser in prahlerischer Y'eise genannt hatte, zum Sprecher aus. Der grosse Goethe benutzte den Faust zur Schilderung des Menschen, das heisst, der gesamten Menschheit. -

Sei Mir Gegrüßt, Du Ewiges Meer! HEINRICH HEINE Meergruß

Sei mir gegrüßt, du ewiges Meer! Heinrich Heine M eergruß.............................................. II Rainer maria rilke Lied vorn M eer............................... 13 Johann Gottfried Herder Von der bildenden Kraft der Meere ....................................................................... 14 Johann Gottfried Herder Von den wahren Meeres bewohnern ..................................................................... 17 ERNST STADLER Resurrectio................. 19 Friedrich N ietzsche Im grossen Schweigen................. 20 Joseph von Eichendorff Die Nachtblume................... 21 Charles Baudelaire Der Mensch und das Meer............ 22 Friedrich N ietzsche Nach neuen Meeren................... 23 Wir gehen am Meer im tiefen Sand, Die Schritte schwer und Hand in Hand. Theodor storm Meeresstrand........................................ 27 Ferdinand freiligrath Sandlieder............................... 28 Heinrich heine »Das Fräulein stand am Meere«........... 31 Max dauthendey »Wir gehen am Meer im tiefen Sand« . 32 Peter Hille Seegesicht...................................................... 33 Ludwig TiECK Das Himmelblau...................................... 34 RAINER MARIA RILKE Sonntag.......................................... 33 wolfgang borchert Muscheln, Muscheln................... 37 Eduard von Keyserling Zu zweien schwimmen.......... 38 klabund Das M eer........................................................... 44 Thomas mann Ruddenbrooks.......................................... 45 kurt Tucholsky Dreißig Grad..................................... -

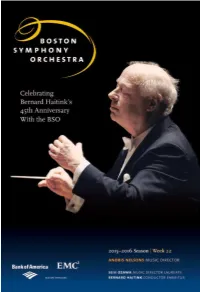

Bernard Haitink 59 Murray Perahia

Table of Contents | Week 22 7 bso news 17 on display in symphony hall 18 bso music director andris nelsons 20 the boston symphony orchestra 23 resonance by gerald elias 32 this week’s program Notes on the Program 34 The Program in Brief… 35 Ludwig van Beethoven 43 Gustav Mahler 51 To Read and Hear More… Guest Artists 57 Bernard Haitink 59 Murray Perahia 62 sponsors and donors 80 future programs 82 symphony hall exit plan 83 symphony hall information program copyright ©2016 Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. program book design by Hecht Design, Arlington, MA cover photo by Constantine Manos cover design by BSO Marketing BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Symphony Hall, 301 Massachusetts Avenue Boston, MA 02115-4511 (617)266-1492 bso.org andris nelsons, ray and maria stata music director bernard haitink, lacroix family fund conductor emeritus seiji ozawa, music director laureate 135th season, 2015–2016 trustees of the boston symphony orchestra, inc. William F. Achtmeyer, Chair • Paul Buttenwieser, President • George D. Behrakis, Vice-Chair • Cynthia Curme, Vice-Chair • Carmine A. Martignetti, Vice-Chair • Theresa M. Stone, Treasurer David Altshuler • Ronald G. Casty • Susan Bredhoff Cohen • Richard F. Connolly, Jr. • Alan J. Dworsky • Philip J. Edmundson, ex-officio • William R. Elfers • Thomas E. Faust, Jr. • Michael Gordon • Brent L. Henry • Susan Hockfield • Barbara W. Hostetter • Stephen B. Kay • Edmund Kelly • Martin Levine, ex-officio • Joyce Linde • John M. Loder • Nancy K. Lubin • Joshua A. Lutzker • Robert J. Mayer, M.D. • Susan W. Paine • John Reed • Carol Reich • Arthur I. Segel • Roger T. Servison • Wendy Shattuck • Caroline Taylor • Stephen R. -

Download PDF Booklet

THE COMPLETE volume 1 SONGBOOK MARK STONE SIMON LEPPER THE COMPLETE volume 1 SONGBOOK MARK STONE SIMON LEPPER THE COMPLETE SONGBOOK volume 1 CHARLES WILFRED ORR (1893-1976) SEVEN SONGS FROM “A S HROPSHIRE LAD ” (Alfred Edward Housman) 1 i Along the field 2’58 2 ii When I watch the living meet 3’17 3 iii The Lent lily 1’54 4 iv Farewell to barn and stack and tree 4’51 5 v Oh fair enough are sky and plain 2’54 6 vi Hughley steeple 3’13 7 vii When smoke stood up from Ludlow 2’58 8 SILENT NOON (Dante Gabriel Rossetti) 4’33 9 TRYSTE NOEL (Louise Imogen Guiney) 3’23 10 THE BREWER ’S MAN (Leonard Alfred George Strong) 1’36 TWO SEVENTEENTH CENTURY POEMS 11 i The Earl of Bristol’s farewell (John Digby) 2’01 12 ii Whenas I wake (Patrick Hannay) 1’37 13 SLUMBER SONG (Noel Lindsay) 2’26 14 FAIN WOULD I CHANGE THAT NOTE (Anonymous) 2’09 15 WHEN THE LAD FOR LONGING SIGHS (Alfred Edward Housman) 2’43 16 THE CARPENTER ’S SON (Alfred Edward Housman) 5’29 17 WHEN I WAS ONE -AND -TWENTY (Alfred Edward Housman) 2’01 18 SOLDIER FROM THE WARS RETURNING (Alfred Edward Housman) 2’57 19 WHEN SUMMER ’S END IS NIGHING arr. Mark Stone (b.1969) 3’31 (Alfred Edward Housman) TWO SONGS FROM “A S HROPSHIRE LAD ” (Alfred Edward Housman) 20 i ’Tis time, I think, by Wenlock town 1’51 21 ii Loveliest of trees, the cherry 3’34 62’07 MARK STONE baritone SIMON LEPPER piano CHARLES WILFRED ORR The unsung hero of English song Part one: The creation of a song-writer Charles James Orr, a captain in the Indian army, met Jessie Jane Coke whilst visiting his aunt in Cheltenham, Gloucestershire. -

I. Glauben Und Wissen

Inhak I. Glauben und Wissen Hildegard von Bingen: Der Mond besteht 11 Egidius Groland: Was man vom Mond fabelt 12 Christian Morgenstern: Der Mondberg-Uhu 22 II. Wie der Mond entstanden ist Karl Immermann: Mondscheinmärchen 25 Brüder Grimm: Der Mond 31 Knud Rasmussen: Der Mond und die Sonne 33 Christian Morgenstern: Der Mond 34 Ludwig Bechstein: Die Spinnerin im Mond 35 Das Mädchen im Mond 37 III. Mondbeglänzte Zaubernacht Sappho: Gesunken ist schon der Vollmond 43 Ludwig Tieck: Brief an Wilhelm Heinrich Wackenroder (12. Juni 1792) 44 Joseph von Eichendorff: Mondnacht 46 Gottfried August Bürger: Auch ein Lied an den lieben Mond 47 Matthias Claudius: Abendlied 50 Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock: Die frühen Gräber 52 Franz Grillparzer: Der Halbmond glänzet am Himmel 53 Johann Wolfgang Goethe: An den Mond (Spätere Fassung) ... $4 Heinrich Heine: Melodie %6 Achim von Arnim: Ritt im Mondschein $7 Theodor Storm: Mondlicht 58 Georg Heym: Getrübt bescheint der Mond die stumme Fläche . 59 Bibliografische Informationen digitalisiert durch http://d-nb.info/994174217 Rudolf G. Binding: Zaubrische Entfremdung ćo Stefan George: Der hügel wo wir wandeln 61 IV. Der Mond, der Kuppler Leopold Friedrich Günther von Goeckingh: An den Mond .... 6$ Achim von Arnim / Clemens Brentano: Ei! Ei! 66 Ludwig Bechstein: Klare-Mond 67 Theokrit: Endymion 71 Lukian: Endymion 72 Rainer Maria Rilke: Mondnacht 74 Heinrich Heine: Mir träumte: traurig schaute der Mond 75 Johann Wolfgang Goethe: An Belinden j6 Theodor Storm: Ständchen yy Nikolaus Lenau: Das Mondlicht 79 Ludwig Tieck: Wunder der Liebe 81 Ludwig Heinrich Christoph Hölty: Die Mainacht 83 Matthias Claudius: Ein Wiegenlied, bei Mondschein zu singen .