Download PDF Booklet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Volume One of the Frederick Delius

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Volume One of the Frederick Delius Songbook to be Released in the United States this September ASHFORD, CONNECTICUT (August 22, 2011) – In honor of the 150th anniversary of the birth of the great English composer Frederick Delius (1862-1934), The Complete Delius Songbook – Volume 1 will be released as a CD in the U.S. on September 13, 2011. This is the first volume in a two-volume series that will comprise the first-ever complete recording of all 61 surviving songs of Frederick Delius for voice and piano. This recording features baritone Mark Stone accompanied by Stephen Barlow on piano. Michael Maglaras of 217 Records is Executive Producer. Produced and released first in the United Kingdom on July 18, 2011 on the Stone Records label, and produced in association with 217 Records, this eventual two-volume journey through the Delius songbook will be a delight to listeners everywhere. Pictured: Stephen Barlow and Mark Stone. “We at 217 Records cannot imagine a finer exponent of the English art song than baritone Mark Stone. That he possesses a superb instrument is clear to everyone who knows his work. But he is also a singer of rare intelligence and refinement, and this recording bears his unmistakable stamp,” said Michael Maglaras. “Stephen Barlow is the logical successor to Gerald Moore. He is a great English pianist who brings not only gracious support to this undertaking, but helps create, in every song, an immediate sense of both the drama and the deeper meaning of Delius’s work.” Volume 1, which includes first-time recordings of five of these songs, features all of Delius’s songs to English and Norwegian texts, the latter being sung in English translation. -

Now We Are 126! Highlights of Our 3 125Th Anniversary

Issue 5 School logo Sept 2006 Inside this issue: Recent Visits 2 Now We Are 126! Highlights of our 3 125th Anniversary Alumni profiles 4 School News 6 Recent News of 8 Former Students Messages from 9 Alumni Noticeboard 10 Fundraising 11 A lot can happen in 12 just one year In Memoriam 14 Forthcoming 16 Performances Kim Begley, Deborah Hawksley, Robert Hayward, Gweneth-Ann Jeffers, Ian Kennedy, Celeste Lazarenko, Louise Mott, Anne-Marie Owens, Rudolf Piernay, Sarah Redgwick, Tim Robinson, Victoria Simmons, Mark Stone, David Stout, Adrian Thompson and Julie Unwin (in alphabetical order) performing Serenade to Music by Ralph Vaughan Williams at the Guildhall on Founders’ Day, 27 September 2005 Since its founding in 1880, the Guildhall School has stood as a vibrant showcase for the City of London's commitment to education and the arts. To celebrate the School's 125th anniversary, an ambitious programme spanning 18 months of activity began in January 2005. British premières, international tours, special exhibits, key conferences, unique events and new publications have all played a part in the celebrations. The anniversary year has also seen a range of new and exciting partnerships, lectures and masterclasses, and several gala events have been hosted, featuring some of the Guildhall School's illustrious alumni. For details of the other highlights of the year, turn to page 3 Priority booking for members of the Guildhall Circle Members of the Guildhall Circle are able to book tickets, by post, prior to their going on sale to the public. Below are the priority booking dates for the Autumn productions (see back cover for further show information). -

2017 Season 2

1 2017 SEASON 2 Eugene Onegin, 2016 Absolutely everything was perfection. You have a winning formula Audience member, 2016 1 2 SEMELE George Frideric Handel LE NOZZE DI FIGARO Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart PELLÉAS ET MÉLISANDE Claude Debussy IL TURCO IN ITALIA Gioachino Rossini SILVER BIRCH Roxanna Panufnik Idomeneo, 2016 Garsington OPERA at WORMSLEY 3 2017 promises to be a groundbreaking season in the 28 year history of Cohen, making his Garsington debut, and directed by Annilese Miskimmon, Garsington Opera. Artistic Director of Norwegian National Opera, who we welcome back nine years after her Il re pastore at Garsington Manor. We will be expanding to four opera productions for the very first time and we will now have two resident orchestras as the Philharmonia Orchestra joins us for Our fourth production will be a revival from 2011 of Rossini’s popular comedy, Pelléas et Mélisande. Il turco in Italia. We are delighted to welcome back David Parry, who brings his conducting expertise to his 13th production for us, and director Martin Duncan Our own highly praised Garsington Opera Orchestra will not only perform Le who returns for his 6th season. nozze di Figaro, Il turco in Italia and Semele, but will also perform the world premiere of Roxanna Panufnik’s Silver Birch at the conclusion of the season. To cap the season off we are very proud to present a brand new work commissioned by Garsington from composer Roxanna Panufnik, to be directed Pelléas et Mélisande, Debussy’s only opera and one of the seminal works by our Creative Director of Learning & Participation, Karen Gillingham, and I of the 20th century, will be conducted by Jac van Steen, who brought such will conduct. -

Sir Colin Davis Anthology Volume 1

London Symphony Orchestra LSO Live Sir Colin Davis Anthology Volume 1 Sir Colin Davis conductor Colin Lee tenor London Symphony Chorus London Symphony Orchestra Hector Berlioz (1803–1869) – Symphonie fantastique, Op 14 (1830–32) Recorded live 27 & 28 September 2000, at the Barbican, London. 1 Rêveries – Passions (Daydreams – Passions) 15’51’’ Largo – Allegro agitato e appassionato assai – Religiosamente 2 Un bal (A ball) 6’36’’ Valse. Allegro non troppo 3 Scène aux champs (Scene in the fields) 17’16’’ Adagio 4 Marche au supplice (March to the Scaffold) 7’02’’ Allegretto non troppo 5 Songe d’une nuit de sabbat (Dream of the Witches’ Sabbath) 10’31’’ Larghetto – Allegro 6 Hector Berlioz (1803–1869) – Overture: Béatrice et Bénédict, Op 27 (1862) 8’14’’ Recorded live 6 & 8 June 2000, at the Barbican, London. 7 Hector Berlioz (1803–1869) – Overture: Les francs-juges, Op 3 (1826) 12’41’’ Recorded live 27 & 28 September 2006, at the Barbican, London. Hector Berlioz (1803–1869) – Te Deum, Op 22 (1849) Recorded live 22 & 23 February 2009, at the Barbican, London. 8 i. Te Deum (Hymne) 7’23’’ 9 ii. Tibi omnes (Hymne) 9’57’’ 10 iii. Dignare (Prière) 8’04’’ 11 iv. Christe, Rex gloriae (Hymne) 5’34’’ 12 v. Te ergo quaesumus (Prière) 7’15’’ 13 vi. Judex crederis (Hymne et prière) 10’20’’ 2 Antonín Dvořák (1841–1904) – Symphony No 9 in E minor, Op 95, ‘From the New World’ (1893) Recorded live 29 & 30 September 1999, at the Barbican, London. 14 i. Adagio – Allegro molto 12’08’’ 15 ii. Largo 12’55’’ 16 iii. -

Download Booklet

MAG IC L A N T Sophie Daneman ~ soprano Beth Higham-Edwards ~ vibraphone E D Alisdair Hogarth ~ piano Anna Huntley ~ mezzo-soprano R A George Jackson ~ conductor Sholto Kynoch ~ piano O N Anna Menzies ~ cello Edward Nieland ~ treble H Sinéad O’Kelly ~ mezzo-soprano Natalie Raybould ~ soprano - T S E Collin Shay ~ countertenor Philip Smith ~ baritone Nicky Spence ~ tenor A Mark Stone ~ baritone Verity Wingate ~ soprano C L N A E R S F L Y R E H C Y B S G N O S FOREWORD Although the thought of singing and acting in front of an audience terrifies me, there is nothing I enjoy more than being alone at my piano and desk, the notes on an empty page yet to be fixed. Fortunately I am rarely overheard as I endlessly repeat words and phrases, trying to find the music in them: the exact pitches and rhythms needed to portray a particular emotion often take me an exasperatingly long time to find. One of the things that I love most about writing songs is that I feel I truly get to know and understand the poetry I am setting. The music, as I write it, allows me to feel as if I am inhabiting the character in the poem, and I often only discover what the poem really says to me when I reach the final bar. This disc features a number of texts either written especially for me (Kei Miller, Tamsin Collison, Andrew Motion, Stuart Murray), or already in existence (Kate Wakeling, Ian McMillan, 4th century Aristotle). -

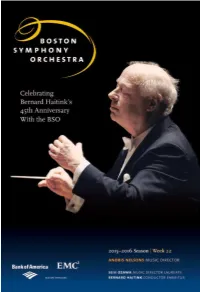

Bernard Haitink 59 Murray Perahia

Table of Contents | Week 22 7 bso news 17 on display in symphony hall 18 bso music director andris nelsons 20 the boston symphony orchestra 23 resonance by gerald elias 32 this week’s program Notes on the Program 34 The Program in Brief… 35 Ludwig van Beethoven 43 Gustav Mahler 51 To Read and Hear More… Guest Artists 57 Bernard Haitink 59 Murray Perahia 62 sponsors and donors 80 future programs 82 symphony hall exit plan 83 symphony hall information program copyright ©2016 Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. program book design by Hecht Design, Arlington, MA cover photo by Constantine Manos cover design by BSO Marketing BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Symphony Hall, 301 Massachusetts Avenue Boston, MA 02115-4511 (617)266-1492 bso.org andris nelsons, ray and maria stata music director bernard haitink, lacroix family fund conductor emeritus seiji ozawa, music director laureate 135th season, 2015–2016 trustees of the boston symphony orchestra, inc. William F. Achtmeyer, Chair • Paul Buttenwieser, President • George D. Behrakis, Vice-Chair • Cynthia Curme, Vice-Chair • Carmine A. Martignetti, Vice-Chair • Theresa M. Stone, Treasurer David Altshuler • Ronald G. Casty • Susan Bredhoff Cohen • Richard F. Connolly, Jr. • Alan J. Dworsky • Philip J. Edmundson, ex-officio • William R. Elfers • Thomas E. Faust, Jr. • Michael Gordon • Brent L. Henry • Susan Hockfield • Barbara W. Hostetter • Stephen B. Kay • Edmund Kelly • Martin Levine, ex-officio • Joyce Linde • John M. Loder • Nancy K. Lubin • Joshua A. Lutzker • Robert J. Mayer, M.D. • Susan W. Paine • John Reed • Carol Reich • Arthur I. Segel • Roger T. Servison • Wendy Shattuck • Caroline Taylor • Stephen R. -

Classical Music

2020– 21 2020– 2020–21 Music Classical Classical Music 1 2019– 20 2019– Classical Music 21 2020– 2020–21 Welcome to our 2020–21 Contents Classical Music season. Artists in the spotlight 3 We are committed to presenting a season unexpected sounds in unexpected places across Six incredible artists you’ll want to know better that connects audiences with the greatest the Culture Mile. We will also continue to take Deep dives 9 international artists and ensembles, as part steps to address the boundaries of historic Go beneath the surface of the music in these themed of a programme that crosses genres and imbalances in music, such as shining a spotlight days and festivals boundaries to break new ground. on 400 years of female composition in The Ghosts, gold-diggers, sorcerers and lovers 19 This year we will celebrate Thomas Adès’s Future is Female. Travel to mystical worlds and new frontiers in music’s 50th birthday with orchestras including the Together with our resident and associate ultimate dramatic form: opera London Symphony Orchestra, Britten Sinfonia, orchestras and ensembles – the London Los Angeles Philharmonic, The Cleveland Symphony Orchestra, BBC Symphony Awesome orchestras 27 Orchestra and Australian Chamber Orchestra Orchestra, Britten Sinfonia, Academy of Ancient Agile chamber ensembles and powerful symphonic juggernauts and conductors including Sir Simon Rattle, Music, Los Angeles Philharmonic and Australian Choral highlights 35 Gustavo Dudamel, Franz Welser-Möst and the Chamber Orchestra – we are looking forward Epic anthems and moving songs to stir the soul birthday boy himself. Joyce DiDonato will to another year of great music, great artists and return to the Barbican in the company of the great experiences. -

Roxanna Panufnik

ROXANNA PANUFNIK COLLA VOCE SINGERS • LONDON MOZART PLAYERS • LEE WARD 1 03388 JC 28pp Roxanna Panufnik – Love Abide SIGCD564 v4.indd 1 30/11/2018 17:01 DEDICATIONS SCHOLA MISSA DE ANGELIS 7 Kyrie ...........................................................................................................................................(2.36) This CD was made with support from 14 principal sponsors who, in return, were able to dedicate For James, Ludovico and Niccolò Canonaco, with all my love, Mamma their track to someone they love – their dedications were read out to the musicians at the start 8 Gloria ........................................................................................................................................(4.23) of each session, so that the sponsors’ individual tracks were performed with their loved ones very To Karen, Nicola, Susan, Anne & Stephen with love from Pa/Tony & Mummy/Joan much in mind. 9 Sanctus & Benedictus .............................................................................................................(4.20) To Nathalie with love from Simon 1 Love Endureth...........................................................................................................................(4.21) 10 Agnus Dei ..................................................................................................................................(5.24) In memoriam Commander R F Jessel DSO OBE DSC Royal Navy & Mrs Winnie Jessel With sincere gratitude for six wonderful years with the Schola, 2006–2012. -

MUSIC | THEATRE | DANCE 2016 –17 PERFORMANCE SEASON 2 MUSIC | THEATRE | DANCE Oakland.Edu/Mtd

MUSIC | THEATRE | DANCE 2016 –17 PERFORMANCE SEASON 2 MUSIC | THEATRE | DANCE oakland.edu/mtd WELCOME Dear Friends of the Arts, It is my pleasure to invite you to our 2016-17 performance season. With our wide range of offerings featuring students, faculty and renowned guest artists, we have something to please everyone. We hope you will be intrigued and perhaps even try something new. Through our partnership with the Chamber Music Society of Detroit, the Juilliard String Quartet will once again grace our concert stage. This time they will perform with Oakland faculty pianist Tian Tian. Guitarist Celino Romero will also return as part of this series, along with Metropolitan Opera soprano Heidi Grant Murphy, pianist Christopher O’Riley and the Imani Winds. Jazz violinist Regina Carter, the Oakland University artist-in-residence, will return to our stage to perform two different concerts. We also welcome contemporary saxophonist Ben Wendel and his group, and Michael Dease who will perform with our student jazz band. Both are Grammy-nominated artists. This season marks the 20th anniversary of the David Daniels Young Artists Concert, which gives each OU Concerto Competition winner a chance to perform with the Oakland Symphony Orchestra. The Oakland Chorale is preparing for a European tour next summer. At this year’s Chorus and Chorale concerts you can hear the music they will perform while on tour. Resident dance company Take Root returns to share their innovative artistry, along with Eisenhower Dance and a range of concerts that showcase student choreography and dance. OU opera students will present Mozart’s The Magic Flute, and the theatre program will present A Chorus Line and Neil Simon’s Rumors, as part of their Mainstage season. -

NEW RELEASE INFORMATION MEDIA CONTACT: Mark Stone At

NEW RELEASE INFORMATION RONALD CORP: STRING, PAPER, WOOD REBECCA DE PONT DAVIES, MEZZO-SOPRANO ANDREW MARRINER, CLARINET MAGGINI STRING QUARTET JOHN TATTERSDILL, DOUBLE BASS CD RELEASE DATE: 25 February 2013 Stone Records is delighted to announce its fourth CD of music by Ronald Corp OBE. This disc is made up of three chamber works, all world-première recordings. Corp’s Third String Quartet is, unlike his earlier two quartets, not intended as programme music, and is simply beautiful music for its own sake. By complete contrast, the central piece is a setting of an adaptation of Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s The Yellow Wallpaper. A thrilling mini psychological drama, this powerful piece grips the listener as the angst of the protagonist is played out. The final piece is a clarinet quintet written in honour of the 19th-century polymath Joseph Crawhall. The committed performances on this disc communicate Corp’s every intention in the varying demands of these diverse compositions. The booklet contains full notes by the composer, as well as illustrating some wood engravings by Joseph Crawhall. This is a wonderful example of an English composer writing engaging, lyric, dramatic music, that will appeal to a wide audience. CRITICAL ACCLAIM “The First Quartet, which draws its inspiration from the character and habitat of that noble bird the bustard, is, like its companion piece, well made and securely in an English tradition voiced with supple energy.” The Telegraph “Ronald Corp is Britain's most prolific choral conductor-composer, and with this work he breaks fascinating new ground. The Dhammapada is a collection of sayings of the Buddha transmitted orally before being written down 2,000 years ago. -

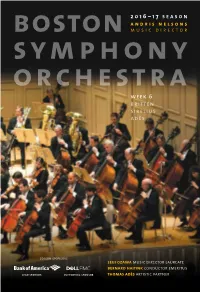

Week 6 2016–17 Season Britten Sibelius Adès

2016–17 season andris nelsons music director week 6 britten sibelius adès season sponsors seiji ozawa music director laureate bernard haitink conductor emeritus lead sponsor supporting sponsor thomas adès artistic partner The most famous 19th-century American painter you’ve never heard of Through January 16, 2017 mfa.org/chase “William Merritt Chase” was organized by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; The Phillips Collection, Presented with generous support from The Mr. and Mrs. Raymond J. Horowitz Foundation Washington, DC; the Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia; and the Terra Foundation for American Art. for the Arts, Inc., and the Deedee and Barrie A. Wigmore Fund in honor of Malcolm Rogers. Additional support from the Betty L. Heath Paintings Fund for the Art of the Americas, and the The exhibition and its publication were made possible with the Eugenie Prendergast Memorial Fund, made possible by a grant from Jan and Warren Adelson. generous support of the Terra Foundation for American Art. William Merritt Chase, The Young Orphan (An Idle Moment) (detail), 1884. Oil on canvas. NA diploma presentation, November 24, 1890. National Academy Museum, New York (221-P). Table of Contents | Week 6 7 bso news 1 5 on display in symphony hall 16 bso music director andris nelsons 18 the boston symphony orchestra 21 brahms’s orchestral voice by jan swafford 2 8 this week’s program Notes on the Program 30 The Program in Brief… 31 Benjamin Britten 39 Jean Sibelius 47 Thomas Adès 65 To Read and Hear More… Guest Artists 69 Thomas Adès 71 Christianne Stotijn 73 Mark Stone 74 sponsors and donors 88 future programs 90 symphony hall exit plan 9 1 symphony hall information the friday preview on november 4 is given by bso assistant director of program publications robert kirzinger. -

Curlew River: a Parable for Church Performance

Friday, November 14, 2014, 8pm Saturday, November 15, 2014, 2pm Zellerbach Hall Curlew River: A Parable for Church Performance Music by Benjamin Britten Libretto by william Plomer, after Jūrō Motomasa Britten Sinfonia & Britten Sinfonia Voices Soloists from the Pacific Boychoir Academy Curlew River is a co-production of the Barbican Centre, London; Cal Performances; Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, New York; and Carolina Performing Arts. These performances are made possible, in part, by Patron Sponsors Annette Campbell-White and Ruediger Naumann-Etienne. Cal Performances’ 8679–867: season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. CAL PERFORMANCES PROGRAM CuRLEw RIVER: A PARABLE FOR CHuRCH PERFORMAnCE ( 1964 ) Music Benjamin Britten (1913–1976) Libretto Willi am Plomer (1903–1973), after Jūrō Motomasa (1395–1431) Direction, Design, Costume, Video Netia Jones Lighting Design Ian Scott CAST Madwoman Ian Bostridge, tenor Abbot Jeremy White, baritone Traveller Neal Davies, bass Ferryman Mark Stone, bass-baritone Spirit of the Boy David Schneidinger Altar Servants Jeroen Breneman, Sivan Faruqui, Louis Pecceu Music Director Martin Fitzpatrick PROduCTIOn TEAM Video and Production Lightmap Production Manager Rachel Shipp Tour Manager Eoin Quirke Video Technician Dori Deng Costume Supervisior Jemima Penny Hair and Makeup Designer Susanna Peretz Production Manager Steve Wald Stage Manager Beth Hoare-Barnes Deputy Stage Manager Jane Andrews Britten Sinfonia Management Nikola White Curlew River U.S Tour Management Askonas Holt Please note that there is