Two Prehistoric Enclosures at the Beeches Playing Field, London Road, Cirencester, Gloucestershire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transfer of Hucclecote Hay Meadows East Site of Special Scientific Interest

Meeting: Cabinet Date: 15 January 2020 Subject: Transfer of Hucclecote Hay Meadows East Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) to Gloucester City Council Report Of: Cabinet Member for Environment Wards Affected: Hucclecote Parish is part of Tewkesbury Borough Key Decision: Yes Budget/Policy Framework: No Contact Officer: Meyrick Brentnall Climate Change and Environment Manager Email: [email protected] Tel: 396829 Appendices: 1. Location Map FOR GENERAL RELEASE 1.0 Purpose of Report 1.1 To update Cabinet on the current situation relating to the use and ownership of Hucclecote Hay Meadows East and recommend that the City Council accepts ownership of the site contingent on receiving a commuted sum of £124,000 from Bovis Homes. 2.0 Recommendations 2.1 Cabinet is asked to RESOLVE that subject to confirmation of receipt of a commuted sum of £124,000 and satisfactory deduction of title, the freehold interest in Hucclecote Hay Meadows East be transferred to the City Council. The transfer to be subject to such conditions as the Head of Place in consultation with the Cabinet Member for Environment and Council Solicitor consider appropriate. 2.2 Following transfer, the site will be managed by the City Council’s Countryside Unit for the purposes of amenity and nature conservation. 3.0 Background and Key Issues 3.1 Hucclecote Hay Meadows is an area of unimproved neutral grassland to the east of Gloucester. The meadows have been managed in a traditional manner for many hundreds of years, and as such they have built up a rare assemblage of vascular plants such as green winged orchid and yellow rattle. -

Gloucester City Council

Gloucester City Council COMMITTEE : GLT CABINET BRIEFING CABINET DATE : 7th DECEMBER 2010 19TH JANUARY 2011 2ND FEBRUARY 2011 SUBJECT : FUTURE OF THE COUNTRYSIDE UNIT DECISION TYPE : FOR INFORMATION WARD : ALL REPORT BY : CABINET MEMBER FOR HERITAGE AND LEISURE NO. OF APPENDICES : NONE REFERENCE NO. : SNR2010_22 1.0 PURPOSE OF REPORT 1.1 To inform members of progress to date regarding the review of the Countryside Unit, and to seek support for a series of measures to realise savings whilst ensuring that the Council’s statutory obligations are met. 2.0 RECOMMENDATIONS 2.1 That Cabinet recognises that: a) the Council no longer directly provides public access to, and interaction with, farm animals b) management of the Countryside unit will pass to the green team within the Regeneration Directorate, building on the existing expertise within that service with regard to ecology and nature conservation, and in particular access to sources of external funding for such work. c) the site of the existing farm buildings at Robinswood will be disposed of in accordance with the Council’s asset management strategy and constitutional provisions. d) it is intended that a small proportion of the receipt will be used to refurbish the existing ranger centre at Robinswood Hill (adjacent premises currently leased to the Gloucestershire Wildlife Trust - GWT). e) subject to agreement of a suitable lease, the GWT will move into the ranger centre in addition to their existing premises and share these facilities with the Countryside Unit. f) large equipment and emergency cattle cover will be relocated to Netheridge Farm (the Barn Owl Centre), funded by a small proportion of the capital receipt for the farm. -

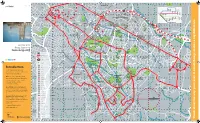

East Gloucester Locality Map & Guide

New sense of direction. of sense New Revised December 2016 December Revised ELMBRIDGE A 4 BUS SERVICE SUMMARY 0 NORTHGATE ST. A3 EASTGATE ST. 852 8 B AR NWO OD RO AD GR E A T W ES TE R Y 8 N A R E O C W A LA D P T FT T O E R SC N R CITY CENTRE ARM B A AR B 13 NW BARNWOOD BUSINESS PARK OO D R OA NO D Y RM 1 A AN BALL W. W N O T HORTON ROAD WOTTON U R B B4 2/2a 0 7 E 3 U B N A E R V T A O L N L S W E T ELL W Z R S R L O E OA O O E D D E C N T A S to Cheltenham U O R N R Y E O V B A A R D E D D BA YO O R Y R O N A K W W R W O OA N O N D R D E A R S O O B A H D C E N D A A L O R H D L C IE R F BARTON U H IC H L C S T R O B A U R D T R O O N © Photograph by Ben Whatley by © Photograph A D S T E E N R N E A A L E L T N N W O HUCCLECOTE L O T L H E C P W R D U E U A L H O G H C R N T I D D R L O IE N F K O and Guide and O CONEY HILL BR HU CC LEC OT E R ST PAUL’S OA Locality Map Map Locality D AB D BE IN YM GL EAD EW AV EL EN L UE ABB East Gloucester Gloucester East EY C MEA ONE D A C Y V 5 HE HIL EN QU L RO U M ER AD E S RO KIN AD GSC ROF P T A RO I AD N S W TREDWORTH I C PEDESTRIAN BRIDGE E K N A R C L O O NE Y H N A IL AD E D L R O E THE OAKS R G RO HIG MAN HFI RO ELD A RO D AD HUCCLECOTE D BIR A CH A O VENUE R V H UL GREEN T C I AN W W L K A L Y S I 5 A E H 41 M U S R N E E E U V C N T A N R W A E E D D N ES W SAINTBRIDGE V O R T L R A O 10 T E D H T GE WALKWAYS R E D O S RI E N V AD A E N E R A BOTS L AB R 8 O OA B D N 3 H RAILWAY I E A T T T E E R W R P G A N A A H A I V B N E CAFÉ S N B W U E E I Y C M K E R A O D BROCKWORTH A CHURCH D A V E Introduction N U E COLLEGE D A Thinktravel provides you with O R IR O DENTIST V R E E R S FA E D information about sustainable travel R L E FI AY W E L DOCTORS IV OB D ON R LE OA ER D YS choices in your local area. -

Local Resident Submissions to the Gloucester City Council Electoral Review

Local resident submissions to the Gloucester City Council electoral review This PDF document contains submissions from local residents with surnames A-H. Some versions of Adobe allow the viewer to move quickly between bookmarks. Local Boundary Commission for England Consultation Portal Page 1 of 1 Gloucester District Personal Details: Name: Theresa Allen E-mail: Postcode: Organisation Name: Comment text: As a resident of , Quedgeley I wish to protest about being moved to Kingsway Ward. We are an established part of Quedgeley, Gloucester. completely inappropriate. Putting the parts of the exsiting Quedgeley into Kingsway would mean that we wouldn't be represented correctly, the needs of Old Quedgeley are completely different to the new and up and coming Kingsway. Uploaded Documents: None Uploaded https://consultation.lgbce.org.uk/node/print/informed-representation/4957 03/03/2015 Local Boundary Commission for England Consultation Portal Page 1 of 1 Gloucester District Personal Details: Name: Mr Argent E-mail: Postcode: Organisation Name: Feature Annotations 2: Use Lobleys Drive as boundary 1: Use Abbeymead Avenue as boundary Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database rights 2013. Map Features: Annotation 1: Use Abbeymead Avenue as boundary Annotation 2: Use Lobleys Drive as boundary Comment text: . We are well served by local services, the majority of which are located in Hucclecote, for example Hucclecote library, the playing fields (King George V Playing Fields), the community centre, dentist, doctors, shops, banks etc. Most of the primary school aged children in our street go to Dinglewell School, which is also in Hucclecote. With this in mind, it makes sense for the voters within our street to have the democratic right to have their say on these vital services that they actually use daily. -

Abbey Jan 2017 County Council

Doubling the Getting First Class Maximum Gloucester Service from Stalking Roads the Post Office Sentence Right >> Page 3 >> Page 2 >> Page 3 Incorporating GloucesterMatters Abbey News from across the City Views Serving the people of Abbeydale and Abbeymead February 2017 ANDREW GRAVELLS REPORTS BACK Andrew reports back on local issues he’s been working on with Gloucester City Council and also Gloucestershire County Council. Andrew has held several to Abbeymead Avenue and a meetings with the Highways new link to Abbeymead Primary England Department to secure school. measures to reduce the surface Andrew is always contactable noise from the M5 which by email or phone, and he holds runs through Abbeydale and an Advice Surgery on the last Abbeymead. Saturday of every month at the Andrew said, "At a Meeting with Abbeydale Community Centre the Government’s Transport between 10am and 11am. Minister, John Hayes MP, in the House of Commons, I was delighted to hear the “This is a great part of Minister tell me and some of Gloucester in which to the Gloucestershire Members Andrew (2nd from left) with Transport Minister (1st on right) at Parliament of Parliament that the work to live.” resurface the stretches of the M5 which run though our area will begin this year." IMPROVEMENTS PLANNED FOR ABBEYMEAD AVENUE He added, "The latest news I have is that the resurfacing will The improvements planned for Abbeymead Avenue aim to reduce journey times, start in mid-February and last whilst improving safety measures for pedestrians and cyclists. approximately 6 weeks, and is The works will include; the provision of an extended left turn lane into North hoped to be completed around Upton Lane (Eastbound); the provision of an extended left turn lane on the the end of March. -

Gloucester Falls Prevention Classes

Gloucester Falls Prevention Classes Day and Time Class Type and Instructor Cost Venue and Cost How to attend More information Monday Falls Prevention £5 Manor Gardens, Contact Matthew www.gfitness.co.uk 10am Matthew Coopey Barnwood Road, on 07872 563266 Gloucester, GL4 3JY Monday Seated Exercise £4 Hamlet Lodge, Contact Tanya on www.gfitness.co.uk 12.30-1.15 Tanya Gennaio Heathville Road, 07875 168 004 Gloucester, GL1 3ET Tuesday Falls Prevention £5 Methodist Church, 9 Contact Matthew www.gfitness.co.uk 9.45 - 10.45 Matthew Harris Carisbrooke Road, on 07795 465 982 Hucclecote, Gloucester, GL3 3QR Tuesday Fit for Life £4 Longlevens Contact Jon on General exercise instructor with 10-11am Jon French Community Centre, 07503 876430 awareness and training of falls Church Road, GL2 prevention exercises 0AJ Tuesday Fit for Life £4 Longlevens Contact Jon on General exercise instructor with 11:15-12:15 Jon French Community Centre, 07503 876430 awareness and training of falls Church Road, GL2 prevention exercises 0AJ Tuesday Falls Prevention £4 Redwell Centre, Contact Matthew www.gfitness.co.uk 12.15pm Matthew Coopey Redwell Road, on 07872 563266 Matson, Gloucester, GL4 6JG Wednesday Fit for Life £4 Hucclecote Contact Jon on General exercise instructor with 10-11am Jon French Community Ctr, 07503 876430 awareness and training of falls prevention exercises www.fallproof.me Gloucester Falls Prevention Classes Hucclecote Road, GL3 3RT Wednesday Active Strength and Balance £5 Churchdown Contact Antonia [email protected] 10-11am (advanced) -

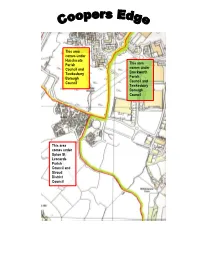

Coopers Edge Boundary Information

This area comes under Hucclecote Parish This area Council and comes under Tewkesbury Brockworth Borough Parish Council Council and Tewkesbury Borough Council This area comes under Upton St Leonards Parish Council and Stroud District Council The Coopers Edge development is shared between 3 parish councils and 2 district councils. The map above shows how the parish boundaries intersect through the development, and 2 of the parishes fall into the Tewkesbury Borough Council authority, and 1 parish falls into Stroud District Council authority. Your parish council is responsible for things like parks and play areas, burial grounds, community facilities, allotments and comments on planning applications and is consulted on policies that the Borough and County Councils implement. The district or borough councils deal with things like bins, planning, benefits and much more. Gloucestershire County Council covers the whole of Coopers Edge and they are responsible for roads, transport, public rights of way, education, and so on. Contacts: Brockworth Parish Council Community Centre Tewkesbury Borough Council Court Road Council Offices Brockworth Gloucester Road Gloucester GL3 4ET Tewkesbury GL20 5TT Email: [email protected] Website: www.brockworth-pc.gov.uk Tel: 01684 295010 Tel: 01452 863123 Website: www.tewkesbury.gov.uk Hucclecote Parish Council Stroud District Council Pineholt Village Hall, Bird Road, Ebley Mill Hucclecote Stroud GL3 3SN GL5 4UB Website: www.hucclecotepc.gov.uk Tel: 01453 766321 Tel: 01452 612485 Website: www.stroud.gov.uk Upton St Leonards Parish Council 11 Broadstone Close Barnwood Gloucester GL4 3TX Email: [email protected] Website: www.uptonstleonards-pc.gov.uk Tel: 01452 621688 . -

Understanding Gloucester 2015

Understanding Gloucester 2015 Produced by the Strategic Needs Analysis Team, Gloucestershire County Council Version: v1.0 Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................ 3 2. Executive summary .................................................................................................... 4 3. Gloucester context ................................................................................................... 13 3.1 About this section ................................................................................................. 13 3.2 Demographics ....................................................................................................... 13 3.3 Deprivation ........................................................................................................... 19 3.4 Life expectancy ..................................................................................................... 26 3.5 Mortality ................................................................................................................ 28 3.6 Economy ............................................................................................................... 31 3.7 Protected characteristics ....................................................................................... 50 3.8 Key messages ...................................................................................................... 57 4. Getting the right start in life ...................................................................................... -

THE LONDON GAZETTE, 12Ra OCTOBER 1990 16017

THE LONDON GAZETTE, 12ra OCTOBER 1990 16017 COTSWOLD DISTRICT COUNCIL 7. Duntisbourne Rouse/Middle Duntisbourne A major addition, comprising the valley between these inter- THE PLANNING (LISTED BUILDINGS AND CONSERVATION AREAS) visible settlements, has resulted in one substantial Conservation ACT 1990 Area. A modern bungalow, west of Duntisbourne Rouse Church, has been deleted. Conservation Areas at Calmsden, Colesbourne, Doughton & 8. Eastleach Highgrove, Fossebridge, Hampen, Ozleworth, Bibury, Three extensions have been made: south-east of The Rectory; east Brockhampton, Coin St. Aldwyn, Daglingworth, Didmarton, of Manor Farm; and south of Bouthrop House. Duntisbourne Abbots/Leer. Duntisbourne Rouse/Middle 9. Hatherop Duntisboume, East leach, Hatherop, Kemble, Lechlade. Poult on, Two major extensions bring Hatherop Park and most of Quenington, Sapper ton, Sevenhampton, Tetbury, Windrush. Williamstrip Park within the designation. A small area of land Notice is hereby given that the Cotswold District Council has along the River Coin has been transferred to Quenington designated Calmsden, Colesbourne, Doughton & Highgrove, Conservation Area. Fossebridge, Hampen and Ozleworth in the county of 10. Kemble Gloucestershire, as Conservation Areas, pursuant to sections 69 and No changes were made in the review of this designation. 70 of the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 11. Lechlade 1990. Substantial additions to Lechlade Conservation Area have been Maps of the designated and reviewed Conservation Areas have made to include the Convent of St. Clothilde; open space east of been deposited at the offices of the Cotswold District Council at the Primary School; meadows between the River Thames and Trinity Road, Cirencester and may be inspected during normal office Little London; and fields north and west of Sherborne House. -

Coney Hill, Barnwood, Hucclecote & Cathedral City

These plans have Coney Hill, been developed following feedback Barnwood, from over 500 tenants and Hucclecote & residents Cathedral City Neighbourhood Priorities and Investment Plan 2019 Building homes and communities Pride. Quality. Integrity. Innovation. where people can thrive WELCOME TO YOUR NEIGHBOURHOOD PRIORITIES AND INVESTMENT PLAN CELEBRATING YOUR COMMUNITY CH has a strong track record of ensuring that tenants are at the heart of what we You have told us that do and are empowered to challenge, develop and improve our services. We are a community-based housing organisation, highly visible within our neighbourhoods, your key priorities are: Gdelivering valued housing services to 5,000 residents in over 4,300 homes. n to improve security in your home and We are committed to ensuring that our residents’ voices are heard throughout the organisation via a number of channels: by strong representation on our board with two tenant board members, community effective challenge though our Tenant Panel and Challenge and Change scrutiny reviews, ongoing n improvements to update transactional customer surveys, online surveys and focus groups, community roadshows, community and modernise kitchens investment in existing groups and venues, social media platforms and the day to day interactions n between our front-line staff and customers. new homes Community Conversation 2018 Over the last 12 months we have had a number of conversations with residents and tenants living in Coney Hill, Barnwood, Hucclecote and Cathedral City; at community events, local drop ins, focus groups and through surveys. We spoke to over 30 residents living in Coney Hill, Providing glitter tattoos at one of our community events Barnwood, Hucclecote and Cathedral City. -

Horsbere Brook Barnwood Gloucester Gloucestershire

HORSBERE BROOK BARNWOOD GLOUCESTER GLOUCESTERSHIRE ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVALUATION For ENVIRONMENT AGENCY CA PROJECT: 3064 CA REPORT: 10035 MARCH 2010 1 HORSBERE BROOK BARNWOOD GLOUCESTER GLOUCESTERSHIRE ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVALUATION CA PROJECT: 3064 CA REPORT: 10035 prepared by Steven Sheldon, Project Supervisor date 05 March 2010 checked by Cliff Bateman, Project Manager date 11 March 2010 approved by Simon Cox, Head of Fieldwork signed date 16 March 2010 issue 01 This report is confidential to the client. Cotswold Archaeology accepts no responsibility or liability to any third party to whom this report, or any part of it, is made known. Any such party relies upon this report entirely at their own risk. No part of this report may be reproduced by any means without permission. © Cotswold Archaeology Building 11, Kemble Enterprise Park, Kemble, Cirencester, Gloucestershire, GL7 6BQ Tel. 01285 771022 Fax. 01285 771033 E-mail: [email protected] © Cotswold Archaeology Horsbere Brook, Barnwood, Gloucester, Gloucestershire: Archaeological Evaluation CONTENTS SUMMARY........................................................................................................................2 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 3 2. RESULTS (FIG 2)................................................................................................ 5 3. DISCUSSION....................................................................................................... 6 4. CA PROJECT -

Duntisbourne Leer, Gloucestershire

Duntisbourne Leer, Gloucestershire Nutbeam Farm Cottage £ 1,295 pcm DuntisbourneCherington, Tetbury Leer, Gloucestershire, Gloucestershire A newly refurbished and beautifully appointed Cotswold stone barn conversion on a private country estate nestled within the stunning rural setting of the Duntisbourne valley between Cirencester and Cheltenham. Introduction Available immediately the deceptively spacious accommodation has been comprehensively refurbished throughout and is presented to a very high standard including brand-new fitted kitchen diner and a luxurious shower /wet room with contemporary style fittings including a double walk in shower. Tastefully decorated throughout, the centrally heated cottage provides well-proportioned and flexible accommodation full of charm and character features with exacting attention to detail. Accommodation A particularly noteworthy feature of the cottage is the generously proportioned master bedroom which occupies the entire upper floor and provides ample space for a king size bed and also features a fabulous deep-sided roll top copper tone bath with contrasting nickel-finish interior. In addition, the cottage offers a most appealing dual aspect sitting room - with beamed ceiling and a feature fireplace with inset log burner and stone hearth, whilst a second reception room, with its access to the patio terrace and views over the rear garden, could make an ideal study, home office perhaps? Thoughtfully designed and laid out over two storeys, further benefits of this superb opportunity include bespoke fitted curtains and blinds throughout as well as new flooring and decoration and the option of a Gigaclear ultrafast fibre broadband connection should you wish. Externally the cottage benefits from a sheltered seating terrace to the rear together with a large open plan lawned garden space (maintenance included within the rent) together with space for off- road parking.