KW 326 Study of Private Schools in Kwara State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Implications of Community Infrastructure Provision in the Development of Medium-Sized Towns in Kwara State Nigeria Adedayo, A

Ethiopian Journal of Environmental Studies and Management EJESM Vol. 5 no.4 (Suppl.2) 2012 IMPLICATIONS OF COMMUNITY INFRASTRUCTURE PROVISION IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF MEDIUM-SIZED TOWNS IN KWARA STATE NIGERIA ADEDAYO, A. and *AFOLAYAN, G.P. http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ejesm.v5i4.S23 Received 20th September 2012; accepted 1st November 2012 Abstract Infrastructure has been recognized as the crux of human settlement development. This paper therefore examines the implications of community provision of infrastructure in the development of medium – sized towns in Nigeria. Medium-sized towns are settlements with population size of between 5,000 and 20,000. Data were collected from both primary and secondary sources. The findings generally revealed a high level of community participation in the provision of such infrastructure as schools, electricity, roads, water, market stalls, health facilities, and town halls. However, variations exist among the medium – sized towns in the type and number of infrastructure provided by community action. Kendall’s Coefficient Concordance (W) used to test the degree of variations in ranks revealed a significant agreement in the ranking. Hierarchical Cluster Analysis used to classify the medium – sized towns based on infrastructure provision produced three classes. The general implication of this study is that, infrastructure provision by community action can lead to a balanced regional development as other smaller towns around the study emulate the action. Recognizing the role of small – sized towns in a balanced regional development process, government should encourage the people through the provision of financial support, machineries and technical know-how in the provision of infrastructure. This paper recommends the integration of community development plans with those of the local government towards achieving even development. -

Kwara Annual School Census Report 2013

ANNUAL SCHOOL CENSUS REPORT 2013-2014 State Ministry of Education and Human Capital Development Kwara State School Census Report 2013-2014 Preface The Y2013/2014 Annual School Census exercise began with sensitization meetings with Public Schools Education Managers and Private Schools Proprietors, which was followed by the update of school list (with support from NGOs), clustering of schools and selection of supervisors/enumerators. The State EMIS Committee then met to deliberate on the modality for the conduct of the exercise. This was followed by the training of supervisors and enumerators, and distribution of questionnaires with the technical and financial support by ESSPIN. The success of the previous census was manifest in its wide acceptance and use in planning, budgeting, monitoring/evaluation within the MDAs and as source of reference by other users. This year exercise which was conducted between 24th February to 7th March began with data collection that was monitored by D/PRSs across the MDAs and ESSPIN Team. Completed forms were returned and screened for face and content validity. Forms with errors or incomplete data were returned for corrections. The data entry officers were trained in four LGA EMIS nodes, spread across the State, where data entry took place. Data cleansing and analysis took place at the State central EMIS in the State Ministry of Education and Human Capital Development. There was a great improvement in data quality and slight improvement in private schools participation as a result of the sensitization engagement with the stakeholders. The LGEA EMIS nodes were strengthened and grassroots commitment enhanced with the data entry that took place at the four centres. -

Nigeria's Constitution of 1999

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 constituteproject.org Nigeria's Constitution of 1999 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 Table of contents Preamble . 5 Chapter I: General Provisions . 5 Part I: Federal Republic of Nigeria . 5 Part II: Powers of the Federal Republic of Nigeria . 6 Chapter II: Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy . 13 Chapter III: Citizenship . 17 Chapter IV: Fundamental Rights . 20 Chapter V: The Legislature . 28 Part I: National Assembly . 28 A. Composition and Staff of National Assembly . 28 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of National Assembly . 29 C. Qualifications for Membership of National Assembly and Right of Attendance . 32 D. Elections to National Assembly . 35 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 36 Part II: House of Assembly of a State . 40 A. Composition and Staff of House of Assembly . 40 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of House of Assembly . 41 C. Qualification for Membership of House of Assembly and Right of Attendance . 43 D. Elections to a House of Assembly . 45 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 47 Chapter VI: The Executive . 50 Part I: Federal Executive . 50 A. The President of the Federation . 50 B. Establishment of Certain Federal Executive Bodies . 58 C. Public Revenue . 61 D. The Public Service of the Federation . 63 Part II: State Executive . 65 A. Governor of a State . 65 B. Establishment of Certain State Executive Bodies . -

Public Administration & Management

Review of Public Administration and Management Vol. 5, No. 9, July 2016 Public Administration & Management Website: www.arabianjbmr.com/RPAM_index.php Publisher: Department of Public Administration Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Nigeria and Zainab Arabian Research Society for Multidisciplinary Issues Dubai, UAE THE IMPACT OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION IN RURAL DEVELOPMENT: A STUDY OF SELECTED LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREAS OF KWARA STATE (2005-2015) 1OTOHINOYI, Samuel, & 3CHRISTOPHER, Seth Ibrahim 1&3Public Administration Department, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria Email: [email protected], [email protected] 2ADAM,U Oyoru Rashida Department of Politics and Governance, Kwara State University Email: [email protected] Abstract Local governments in Nigeria are to provide services aimed at improving the welfare of people living within their jurisdictions. The study examined the impact of local government administration in rural development with specific reference to selected local government areas of Kwara state. Data for the study were generated from both primary and secondary sources. The study revealed that, the amount of statutory allocation received by Baruten and Ilorin West local governments affected their developmental performances; it also revealed that, interference of Kwara state government in the activities of local government has negatively affected their constitutional roles to the local populace. The study recommended that, the tax base and financial allocation of local government from the State and federal governments should be increased given their present level of functions and also, both local governments should judiciously make use of the available funds to meet their constitutional functions. Besides local governments, should be given freedom in carrying out their constitutional functions by the higher governments especially the Kwara state government. -

Journal of Geography and Regional Planning Volume 8 Number 2 February 2015 ISSN 2070-1845

Journal of Geography and Regional Planning Volume 8 Number 2 February 2015 ISSN 2070-1845 ABOUT JGRP Journal of Geography and Regional Planning (JGRP) is a peer reviewed open access journal. The journal is published monthly and covers all areas of the subject. Journal of Geography and Regional Planning (JGRP) is an open access journal that publishes high‐quality solicited and unsolicited articles, in all areas of Journal of Geography and Regional Planning such as Geomorphology, relationship between types of settlement and economic growth, Global Positioning System etc. All articles published in JGRP are peer‐ reviewed. Contact Us Editorial Office: [email protected] Help Desk: [email protected] Website: http://www.academicjournals.org/journal/JGRP Submit manuscript online http://ms.academicjournals.me/ Editors Prof. Prakash Chandra Tiwari, Dr. Eugene J. Aniah Department of Geography, Kumaon University, Department of Geography and Regional Planning, University of Calabar Naini Tal, Calabar, Uttarakhand, Nigeria. India. Dr. Christoph Aubrecht AIT Austrian Institute of Technology Foresight & Policy Development Department Associate Editor Vienna, Austria. Prof. Ferreira, João J Prof. Helai Huang University of Beira Interior ‐ Portugal. Urban Transport Research Center Estrada do Sineiro – polo IV School of Traffic and Transportation Engineering Portugal. Central South University Changsha, China. Dr. Rajesh K. Gautam Editorial Board Members Department of Anthropology Dr. H.S. Gour University Sagar (MP) Dr. Martin Balej, Ph.D India. Department of Development and IT Faculty of Science Dulce Buchala Bicca Rodrigues J.E. Purkyne University Engineering of Sao Carlos School Ústí nad Labem, University of Sao Paulo Czech Republic. Brazil, Prof. Nabil Sayed Embabi Shaofeng Yuan Department of Geography Department of Land Resources Management, Faculty of Arts Zhejiang Gongshang University Ain Shams University China. -

Characterization of Baruten Local Government Area of Kwara State (Nigeria) Fireclays As Suitable Refractory Materials

Nigerian Journal of Technology (NIJOTECH) Vol. 37, No. 2, April 2018, pp. 374 – 386 Copyright© Faculty of Engineering, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Print ISSN: 0331-8443, Electronic ISSN: 2467-8821 www.nijotech.com http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/njt.v37i2.12 CHARACTERIZATION OF BARUTEN LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA OF KWARA STATE (NIGERIA) FIRECLAYS AS SUITABLE REFRACTORY MATERIALS Y. L. Shuaib-Babata1,*, S. S. Yaru2, S. Abdulkareem3, Y. O. Busari4, I. O. Ambali5, K. S. Ajao6 and G. A. Mohammed7 1, 4, 5, 6, 7 DEPT. OF MATERIALS & METALLURGICAL ENGR., UNIVERSITY OF ILORIN, ILORIN, KWARA STATE NIGERIA 2, DEPARTMENT OF MECHANICAL ENGINEERING, FEDERAL UNIV. OF TECHNOLOGY, AKURE, ONDO STATE, NIGERIA 3, DEPARTMENT OF MECHANICAL ENGINEERING, UNIVERSITY OF ILORIN, ILORIN, KWARA STATE, NIGERIA E-mail addresses: [email protected], [email protected], 3 [email protected], 4 [email protected], 5 [email protected], 6 [email protected], 7 [email protected] ABSTRACT Studies have shown that adequate attention needs to be paid on processing of solid minerals that are potentially available in Nigeria to address its economic problem. Clays from five major towns in Baruten Local Government Area, Kwara State, Nigeria were examined using ASTM guidelines to determine their suitability for refractory applications. The clay samples were classified as Alumino-Silicate refractories due to high values of Al2O3 and SiO2. The results showed apparent porosity (19.4-25.6%), bulk density (1.83-1.90 g/cm3), cold crushing strength (38.7-56.1 N/mm2), linear shrinkage (4.4 – 9.3%), clay contents (52.71-67.83%), moisture content (17.0-23.6%), permeability (68-82 cmsec-1), plasticity (16.7-30.4%), refractoriness (>1300oC) and Thermal Shock Resistance (23-25 cycles) for the clay samples, which were measurable with the established standards for fireclays, refractory clays/brick lining or alumina-silicates and kaolin. -

1 1 0190004 Government Secondary School, Ilorin 1902 Tanke/Basin

NATIONAL EXAMINATIONS COUNCIL PMB 159, MINNA NIGER STATE SENIOR SCHOOL CERTIFICATE EXAMINATION (EXTERNAL) 2019 NOV/DEC SSCE LIST OF CENTRES AND CUSTODIAN POINTS KWARA STATE 019 S/n Neighbourhood Senatorial S/n Centre Code Name of Centre Neighbourhood Name Custodian Point L G A Per CP Code District 1. NECO OFFICE ILORIN 1 1 0190004 Government Secondary School, Ilorin 1902 Tanke/Basin NECO Office Ilorin Ilorin East Kwara Central 2 2 0190008 Government Day Secondary School, Tanke, Ilorin 1902 Tanke/Basin NECO Office Ilorin Ilorin South Kwara Central 3 3 0190085 Government Day Secondary School, Fate 1902 Tanke/Basin NECO Office Ilorin Ilorin South Kwara Central 4 4 0190013 Community Secondary School, Baboko, Ilorin 1904 Baboko/Sawmill NECO Office Ilorin Ilorin South Kwara Central 5 5 0190005 Army Day Secondary School, Sobi 1914 Gambari/Shao NECO Office Ilorin Ilorin South Kwara Central 6 6 0190015 Government High School, Ilorin 1915 Adeta/Oloje NECO Office Ilorin Ilorin East Kwara Central 8 8 0190032 Community Secondary School, Ogele 1916 Odota/Otte NECO Office Ilorin Ilorin East Kwara Central 9 9 0190078 Government Day Secondary School Airport, Ilorin 1916 Odota/Otte NECO Office Ilorin Ilorin East Kwara Central 10 10 0190116 Lasoju Comprehensive High School, Lasoju 1916 Odota/Otte NECO Office Ilorin Ilorin East Kwara Central 3. UNITY BANK OFFA 11 1 0190019 Ansarul-Deen College, Offa 1905 Offa/Oyun Unity Bank Offa Offa Kwara South 12 2 0190023 Erin-Ile Secondary School, Erin-Ile 1905 Offa/Oyun Unity Bank Offa Offa Kwara South 4. UNION BANK ORO 13 1 0190028 Jammat Nasir Islamic College, Oro 1906 Oro Union Bank Oro Irepodun Kwara South 5. -

Local Government and Rural Development

Local Government and Rural development LOCAL GOVERNMENT AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT: "'., ' AN APPRAISAL,OEBARUTEN AND·ILORIN WEST LOCAL GOVERNMENTS ". , ;'/... bY Bello, Matthew Funsho Abstract Local governments in Nigeria are to provide services aimed at improving the welfare of people liVing', ~1flMir jurisdictions. We investigated on the reason(s) why Baruten and Ilorin West Local Governments' Perf01't1l/:lflUJelJr1!e/tlw expectations from the populace despite the funds they received from the Federation Account and the KwalJl...4.Wfe Government over the years. The scope of the study covered the period of 1999 - 2007. Data for the study were ger.eTated from both primary. andsecondary sources.' The instruments used for primary data include; interview and questionnaire ~liile secondary source includes; books, articles, published materials-and so on. The research used two hypotheses whicli'state that, "the amount of statutory allocation received by Baruten and Ilorin-West Local Government, does not affecttkeir Developmental Performance" and also. "that interference of Kwara state government in the activities of Baruten and, llt;JriTJ West local governments has positive effect on their performance ". The generated data were analysed using. tables,si1lJP.le percentage and chi-square statistical tool in testing the hypotheses jormulated. The study revealed that. the amount of statutory allocation received by Baruten and Ilorin West local governments affected their developmental peifdmfilrrces; it also revealed that. interference of Kwara State government in the activities of Baruten and Ilorin West local governments has negatively affected their constitutional roles to the localpopulace. The study recommended that. the tax base and financial allocation of-BarutenandIlorin West local governments from-the higher governments slwfdd be i~d.'8ilt4n their present level of junctions and also, both local governments should judiciously make use of the available /rtn48;1P.~~ their constitutional functions. -

Exit Date the U-Turn LETTERS

May Day: Labour in Limbo Adolphus Karibi-Whyte Exit Date The U-Turn LETTERS country and the delay by the ministry of obtained approval to pay relevant fées Shabby Treatment external affairs to provide a realistic rate demanded by school authorities based of conversion for expenses incurred in on the practice in Nigeria. This policy Whatever offence General Olusegun the local currency to the Naira for affected the children of all home-based Obasanjo, former head of state and purposes of making returns to officers in Buenos Aires. The officers General Shehu Musa Yar'Adua, his one headquarters. It might interest your concerned of course had to pay all extras time deputy, might have committed, their readers to note that when we first went to outside the approved practice. I wonder manner of arrest, detention and the initial Buenos Aires in 1987, the local currency why the ambassador's daughter is being denial of military authorities that they was exchanging at three to one dollar. By singled out when the practice, which I were aware of the former's arrest goes in 1991, the rate had jumped to ten thousand incidentally inherited, covered all no small way to show that Nigeria, nay Australes to one US dollar. The embassy children of home-based officers. Nigerians do not have any iota of respect still had to file returns up to 1992 using The conference in New York in for their former leaders. (Cover March the conversion rate approved for 1988, August, 1992, was a Nigerian federal 27). thus giving the false impression of over government approved activity under the John A. -

Establishment of Mycoplasma Laboratory. University of Ilorin. Final

Final Report Establishment of diagnostic laboratory for mycoplasma diseases of livestock at Ilorin University with particular reference to CBPP and CCPP Dr Isaac Dayo Olorunshola DVM, MSc, PhD, MPH Senior Lecturer (Mycoplasmology Specialty), Department of Veterinary Microbiology Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Ilorin. NIGERIA email:[email protected] Dr Robin Nicholas MSc, PhD, FRCPath Consultant, The Oaks, Nutshell Lane, Upper Hale, Farnham, Surrey GU9 0HG, UK Email: [email protected] Executive summary Contagious bovine (CBPP) and caprine pleuropneumonia (CCPP) are OIE-listed diseases because of the socio-economic impact they have mainly on smaller holdings often on marginal land in Asia and Africa. Despite some successful attempts in Nigeria at controlling CBPP in the 1970s there is substantial evidence that the disease is endemic in many parts of the country. CCPP, on the other hand, has been suspected based on clinical and pathological signs but has not been confirmed by laboratory tests. Furthermore, there have been no surveys to show its distribution in the country. Following the purchase of equipment, test kits and reagents and refurbishment and training, a mycoplasma laboratory was established and commissioned in July 2020 by the Vice Chancellor of the University of Ilorin, Kwara state, western Nigeria. A commercial competitive ELISA for the serological detection of the causative agent of CBPP, Mycoplasma mycoides subsp mycoides, was used to screen abattoirs in the state. Between 6 and 135 samples were taken from each; the percentage of positive sera varied between 0 and 13.5%. However, where more than 40 samples were taken seroprevalence was shown to be between approximately 7 and 14%. -

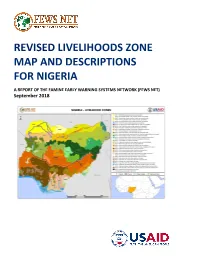

Nigeria Livelihood Zone Map and Descriptions 2018

REVISED LIVELIHOODS ZONE MAP AND DESCRIPTIONS FOR NIGERIA A REPORT OF THE FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS NETWORK (FEWS NET) September 2018 NIGERIA Livelihood Zone Map and Descriptions September 2018 Acknowledgements and Disclaimer This report reflects the results of the Livelihood Zoning Plus exercise conducted in Nigeria in July to August 2018 by FEWS NET and partners: the Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (FMA&RD) and the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), the United Nations World Food Program, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, and various foundation and non-government organizations working to improve the lives and livelihoods of the people of Nigeria. The Livelihood Zoning Plus workshops whose results are the subject of this report were led by Julius Holt, consultant to FEWS NET, Brian Svesve, FEWS NET Regional Food Security Specialist – Livelihoods and Stephen Browne, FEWS NET Livelihoods Advisor, with technical support from Dr. Erin Fletcher, consultant to FEWS NET. The workshops were hosted and guided by Isa Mainu, FEWS NET National Technical Manager for Nigeria, and Atiku Mohammed Yola, FEWS NET Food Security and Nutrition Specialist. This report was produced by Julius Holt from the Food Economy Group and consultant to FEWS NET, with the support of Nora Lecumberri, FEWS NET Livelihoods Analyst, and Emma Willenborg, FEWS NET Livelihoods Research Assistant. This report will form part of the knowledge base for FEWS NET’s food security monitoring activities in Nigeria. The publication was prepared under the United States Agency for International Development Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) Indefinite Quantity Contract, AID-OAA-I-12-00006, Task Order 1 (AID-OAA-TO-12- 00003), TO4 (AID-OAA-TO-16-00015). -

Impact of Computer in Public Secondary Schools in Ilorin Metropolis, Kwara State

IMPACT OF COMPUTER IN PUBLIC SECONDARY SCHOOLS IN ILORIN METROPOLIS, KWARA STATE BY AHMED ABIODUN TAOFIK DEPARTMENT OF COMPUTER SCIENCE [email protected] [email protected] SCHOOL OF INFORMATION AND COMMUNICATION TECHNOLOGY (SICT), KWARA STATE COLLEGE OF ARABIC AND ISLAMIC LEGAL STUDIES, (CAILS) ILORIN FEBURARY, 2017 ABSTRACT This paper focuses on the impact of computer in public secondary schools in Ilorin metropolis, Kwara State. The impact of computer and how it is expected to exposed students and teachers to the world of knowledge at this jet age. It gives brief history of computer education in Kwara state The objective of this study is to find out the contribution of information and communication technology and computers in public secondary schools in Ilorin metropolis, Kwara State. Simple random sampling technics was used to select ten (10) of forty (40) public secondary schools offering computer education. Similarly the purposive sampling technics was used in selecting eight (8) students and two (2) teachers from each of the ten (10) selected schools. This gave a total of One Hundred (100) respondents used for the study. A self -structured questionnaire titled impact of computer on public secondary education questionnaire (IOCOPSSEQ) was used. The finding of this studies indicate the contribution of computer teaching across public secondary schools in Ilorin metropolis and also while knowledge of computer application often contribute to student learning. Keywords: Computer, Information and Communication Technology, Parent Teachers’ Association. Introduction Education as a concept has been widely accepted not just asa means of social change but a means through which cherished values of a society can be transmitted from one generation to another.