EMU and Portugal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Information Leaflet “Cross-Border Cooperation Programme ENPI

TERRITORIAL COOPERATION 2007-2013 CROSS-BORDER COOPERATION PROGRAMME – ENPI MEDITERRANEAN SEA BASIN The publication might be co-financed by the European Union August 2010 This document provides basic information and it is not exhaustive. Further information about the Programme may be found at the Structural Funds and Cohesion Fund website of the Planning Bureau (www.structuralfunds.org.cy) under the European Territorial Cooperation Programmes category as well as at the Programme’s website (www.enpicbcmed.eu). 1 Cross-border Cooperation Programme ENPI Mediterranean Sea Basin, 2007- 2013 The European Neighbourhood Policy was established under the framework of the 2004 enlargement of the EU, in order to avoid the creation of new dividing lines between the enlarged EU and neighbouring countries and also to enhance stability, security and prosperity of all parties involved. The actions under the framework of this policy are financed by the Financing Instrument of the European Neighbourhood and Partnership Policy. Cyprus participates only in one of the programmes of this policy, the Cross-border Cooperation Programme ENPI Mediterranean Sea Basin together with regions from Algeria, Egypt, France, Greece, Italy, Jordan, Libya, Morocco, Portugal, Spain, Syria, Tunisia, Turkey, the UK, Israel, Lebanon, Malta and the Palestinian Authority, as indicated below: Eligible countries and territories* Cyprus: the whole country Egypt: Marsa Matruh, Al Iskandanyah, Al Buhayrah, Kafr ash Shaykh, Ad Daqahliyah, Dumyat, Ash Sharquiyah, Al Isma’iliyah, Bur Sa’id, -

Financiai Innovations for SME Cre"Ditandequity Financing: The

..--:--' CFE/SME(2005)8/REV3 ANNEXI: A SYNOPTIC VIEW OF THE CONFERENCE STRUCTURE OFFICIAL OPENING Tuesday, 28 am PLENARY KEYNOTE SESSION: March "THE SME FINANCING GAP: THEORY ANO EVIOENCE" pm ParaUel WORKSHOP A: Session 1: TheNature Df The Workshops Credit Financing for Market Failure In Relation To SMEs: Constraints' Debt Financing and Innovative' Solutions WORKSHOPB: 1: The Nature Df The Equity . Financing .Market Failure,' In Relation To for SMEs imd" the DebtFinancing?- Role of Government . Wednesday, 29 am March ,8ession 2: What 'Role" For ,'Government? pm Plenary Session Financiai Innovations For SME Cre"ditAndEquity of the ParaUel Financing: The Contributions oÍ 'Markets And Workshops Governments Thursday, 30 am FINAL PLENARY SESSION: March CONCLUSIONS ANO RECOMMENOA TIONS BY CHAIRS 15 CFE/SME(2005)8/REV3 DRAFT CONFERENCE PROGRAMME MONDA Y 27 MARCH 2006 OFFICIAL OPENING 18:00-20:00 Mr. Luiz Inado Lula da Silva President of Brazil Mr. Luiz Fernando Furlan Minister ofDeveloprnent, Industry and Foreign Trade, Brazil High Levei Officials ji-om Brazil and invited countries Mr. Herwig Schlõgl Deputy Secretary-General, OECD KEYNOTE ADDRESS: Mr. Takao Suzuki, Chairman, Organization for Small & Medium Enterprises and Regional innovation, lapan 16 CFE/SME(2005)8/REV3 MORNING, TUESDA Y 28 MARCH 2006 PLENARY KEYNOTE SESSION: "THE SME FINANCING GAP: THEORY AND EVIDENCE" CHAIR: Mr. Henvig Schlõgl, Deputy Secretary-General, OECD Presentation o/the OECD Secretariat Background Paper: 9:00 - 9:15 M. André Laboul, Directorate for FinanciaI and Enterprise Affairs, OECD Mr. Hugh Morgan Williams, Chair cm SME Council and Vice Chair, Entrepreneurship and SME Committee, Union des Industries de la Communauté Européenne (UNICE), (invited) or Mr. -

The Eurogroup & the Atlantic Council of the United States

This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu THE EUROGROUP & THE ATLANTIC COUNCIL OF THE UNITED STATES 1992 EUROGROUP WASHINGTON CONFERENCE SECURITY CHALLENGES IN THE 1990s: NATO'S CONTRIBUTION TO AN UNDIVIDED EUROPE JUNE 21 & 22, 1992 JW MARRIOTT HOTEL, GRAND BALLROOM 1331 PENNSYLVANIA AVENUE, N.W. WASHINGTON, D. C. Page 1 of 72 This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu 1992 EUROGROUP WASHINGTON CONFERENCE THE EUROGROUP The EUROGROUP was established in 1968 as an informal grouping of Defense Ministers of European governments within the framework of the NATO alliance. It aims to insure that the contribution which its twelve members-Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Greece, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Turkey, and the United Kingdom- TABLE OF CONTENTS make to Alliance defense is as strong and cohesive as possible. It lays special stress on promoting practical cooperation and has technical sub- groups working in the fields of training, logistics, communcations, military medicine, and operational concepts. The defense ministers of the EUROGROUP countries meet every six months to direct this activity and to discuss major defense and security issues, Program ..................................................... especially those related to NATO's defense planning business. In addition, 2 the EUROGROUP seeks to advance open dialogue on Issues of European defense and the NATO alliance. EUROGROUP Delegations . .4 THE WASHINGTON CONFERENCE Distinguished Observers . 9 The annual conference in Washington, D.C., contributes to the multina- tional dialogue by inviting U.S. government officials, members of the private sector, and national and international media to join EUROGROUP Biographies delegations, ministers of defense, and permanent representatives to NATO in an open forum to discuss European and trans-Atlantic security issues. -

Guide to the Council of the European Communities : December 1989

General Secretariat of the Council GUIDE TO THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES December 1989 General Secretariat of the Council GUIDE TO THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES Brussels, December 1989 This publication is also available in the following languages: ES ISBN 92-824-0702-0 DA ISBN 92-824-0703-9 DE ISBN 92-824-0704-7 GR ISBN 92-824-0705-5 FR ISBN 92-824-0707-1 IT ISBN 92-824-0708-X NL ISBN 92-824-0709-8 PT ISBN 92-824-0710-1 Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this publication Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 1990 ISBN 92-824-0706-3 Catalogue number: BX-57-89-176-EN-C © ECSC-EEC-EAEC, Brussels · Luxembourg, 1990 Printed in Belgium CONTENTS Page Council of the European Communities 5 Presidency of the Council 7 Conference of the Representatives of the Governments of the Member States 8 List of representatives of the governments of the Member States who regularly take part in Council meetings 9 Belgium 10 Denmark 11 Federal Republic of Germany 12 Greece 15 Spain 17 France 19 Ireland 21 Italy 23 Luxembourg 29 Netherlands 30 Portugal 32 United Kingdom 35 Permanent Representatives Committee 39 Coreper II 40 Coreper I 42 Article 113 Committee 44 Special Committee on Agriculture 44 Standing Committee on Employment 44 Budget Committee 44 Scientific and Technical Research Committee (Crest) 45 Education Committee 45 Committee on Cultural Affairs 46 Select Committee on Cooperation Agreements between the Member States and third countries 46 Energy Committee 46 Standing Committee on Uranium -

7 November 1990)

Report by the WEU Assembly on the consequences of the invasion of Kuwait (7 November 1990) Caption: In a report presented to the Assembly of Western European Union (WEU) on 7 November 1990, the Defence Committee assesses developments in the situation in the Persian Gulf after Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait and emphasises the importance of carrying through WEU actions to help the United Nations in the settlement of the Gulf crisis. Source: Proceedings. Thirty-sixth ordinary session. Second part, III. Assembly documents. Paris: Assembly of Western European Union, December 1990. 346 p. "Consequences of the invasion of Kuwait: continuing operations in the Gulf region. Document 1248. 7 November 1990", p. 188. Copyright: (c) Translation CVCE.EU by UNI.LU All rights of reproduction, of public communication, of adaptation, of distribution or of dissemination via Internet, internal network or any other means are strictly reserved in all countries. Consult the legal notice and the terms and conditions of use regarding this site. URL: http://www.cvce.eu/obj/report_by_the_weu_assembly_on_the_consequences_of_th e_invasion_of_kuwait_7_november_1990-en-c3f8d6ba-c1ae-4071-b184- 4379a7051c87.html Last updated: 05/07/2016 1/47 Document 1248 7th November 1990 Consequences of the invasion of Kuwait: continuing operations in the Gulf region REPORT 1 submitted on behalf of the Defence Committee2 by Mr. De Hoop Scheffer, Rapporteur TABLE OF CONTENTS RAPPORTEUR'S PREFACE DRAFT RECOMMENDATION on the consequences of the invasion of Kuwait: continuing operations in the Gulf region EXPLANATORY MEMORANDUM submitted by Mr. De Hoop Scheffer, Rapporteur I. Introduction II. Developments from mid-September to date (i) Second extraordinary meeting of the WEU Council of Ministers, Tuesday, 18th September 1990 (ii) Meeting of Defence and Political Committees followed by Presi dential Committee meeting, Thursday, 20th September 1990 (iii) Assembly delegation to examine the WEU naval deployment in the Gulf III. -

Mário Soares. a Politician and President of Unwritten Constitutional Competences

Mário Soares. A Politician and President of Unwritten Constitutional Competences. Rebecca Sequeira Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena Content 1. Introduction.................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Charisma and Rhetoric in Theory and Practice............................................................. 3 3. The Role of Soares in the Revolutionary Phase 1974-1976........................................ 6 3.1 The Opposition in the Estado Novo and the End of the Dictatorship........................ 6 3.2 The Portuguese Parties and their Role in the Development of the Portuguese Democracy …........................................................................................................................... 9 3.2.1 Partido Socialista................................................................................................ 9 3.2.1.1 The Development and Role of the PS in the Revolutionary Phase................................................................................................................ 10 3.2.1.2 Organization and Composition of the PS..................................... 15 3.2.2 Partido Comunista de Portugal........................................................................ 16 3.2.3 Partido Popular Democrático/ Partido Social Democrata......................... 19 3.2.4 Centro Democrático Social/ Partido Popular............................................... 21 3.3 The Birth of the II. Republic: The Legal Validity -

Here the Programme

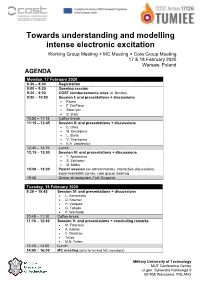

Towards understanding and modelling intense electronic excitation Working Group Meeting + MC Meeting + Core Group Meeting 17 & 18 February 2020 Warsaw, Poland AGENDA Monday, 17 February 2020 8:30 – 9:00 Registration 9:00 – 9:20 Opening session 9:20 – 9:30 COST reimbursements rules (A. Benitez) 9:30 – 10:50 Session I: oral presentations + discussions • Rivera • F. Da Pieve • Solov’yov • B. Ziaja 10:50 – 11:15 Coffee break 11:15 – 12:45 Session II: oral presentations + discussions • E. Oliva • M. Dimitrijević • L. Stella • V. Tkachenko • K.A. Janulewicz 12:45 – 14:15 Lunch 12:15 – 15:00 Session III: oral presentations + discussions • T. Apostolova • S. Zakharov • M. Müller 15:00 – 18:00 Poster session (w/ refreshments), interactive discussions, experimentalist corner, core group meeting 19:00 Dinner at restaurant Folk Gospoda Tuesday, 18 February 2020 9:30 – 10:45 Session IV: oral presentations + discussions • L. Varvarezos • O. Kravcov • H. Vazquez • G. Tsibidis • P. Wachulak 10:45 – 11:10 Coffee break 11:10 – 12:40 Session V: oral presentations + concluding remarks • M. Tatarakis • K. Kaleris • V. Dimitriou • Tazes • M.B. Yelten 12:40 – 14:00 Lunch 14:00 – 16:00 MC meeting (only for invited MC members) Military University of Technology MUT Conference Center ul.gen. Sylwestra Kaliskiego 9 00-908 Warszawa, POLAND DETAILED PROGRAMME ORAL PRESENTATIONS SESSION I (Monday, 9:30 – 10:50) ***80 min Multiscale approach to the interaction of intense femtosecond laser pulses with plasmonic nanoparticles I.1 Antonio Rivera Institute of Nuclear Fusion, -

Psi-K Daresbury Science and Innovation Campus Warrington WA4 4AD

Psi-k Daresbury Science and Innovation Campus Warrington WA4 4AD 14th of January, 2010 Dear Dr. Damian Jones (cc: Dr. Peter H. Dederichs), I am writing to confirm that the quantity of 6400.00 Euros has been received by the CENTRO DE CIENCIAS DE BENASQUE “PEDRO PASCUAL”. Please find a detailed description of the expenses that amount to the sum of 8000.00 Euros agreed by the Psi-k. We look forward to receive the remaining 1600.00 Euros. The money has been used as financial support to cover the registration fee, travel and accommodation expenses for students attending the school “Time- Dependent Density-Functional Theory” held in Benasque from the 31st of August until the 9th of September, 2008. Please find enclosed a table showing the distribution of funding amongst the students and lectures. Copies of the bills will be sent to you by surface mail as soon as possible. Dr Angel Rubio, the scientific organiser of the school will send a detailed scientific report in due time. Yours sincerely, José Ignacio Latorre Director PSIK: Funding distribution Amount Daily Travel Accomodation received Surname First name NationalityAllowance support Payment support Return (euros) BURGESS Robertson Australian 523.60 0.00 0.00 583.00 6.60 1100.00 ESPINOSA Leonardo Colombia 224.40 76.50 0.00 116.50 17.40 400.00 ETZ Corina Romanian 0.00 100.00 0.00 800.00 0.00 900.00 FUKS Johanna German 224.40 115.90 0.00 560.00 0.30 900.00 GARCIA Pablo Spain 336.60 92.53 0.00 471.00 0.13 900.00 GRUNING Myrta Italian 299.20 78.84 217.96 304.00 0.00 900.00 CONOR Hogan Irish 149.60 249.75 50.65 150.00 0.00 600.00 NATARAJAN Bhaarathi Indian 561.00 41.48 0.00 305.00 7.48 900.00 SURAUD Eric French 187.00 163.40 0.00 350.00 0.40 700.00 COFFEE BREAK 700.00 Total 8000.00 Euros TIME-DEPENDENT DENSITY-FUNCTIONAL THEORY: PROSPECTS AND APPLICATIONS 4th International Workshop and School Benasque (Spain), January 2 – 15, 2010 A. -

Investigação No Âmbito Do Projecto “Patronagem Política Em Portugal”

Investigação no âmbito do projecto “Patronagem Política em Portugal” Financiado pela FCT (Ref: PTDC/CPO/65419/2006) Co-financiado, desde 2010, pelo Fundo Europeu de Desenvolvimento Regional (FEDER) através do Eixo I do Programa Operacional Fatores de Competitividade, POFC – COMPETE (Ref: COMPETE FCOMP-01-0124-FEDER-007115) Research of the “Political Patronage in Portugal” project Funded by FCT (Ref: PTDC/CPO/65419/2006) Co-financed, since 2010, by the Fundo Europeu de Desenvolvimento Regional (FEDER) through the Eixo I do Programa Operacional Fatores de Competitividade, POFC – COMPETE (Ref: COMPETE FCOMP-01-0124-FEDER- 007115) Revista Enfoques, Vol. VII N° 11, 2009 pp. 441/470 Weak Societal Roots, Strong Individual Patrons? Patronage & Party Organization in Portugal Carlos Jalali - [email protected] Universidade de Aveiro, Portugal Marco Lisi - [email protected] Instituto de Ciências Sociais - Universidade de Lisboa, Portugal We examine why patronage may constitute an important dimension of analysis in the study of Portuguese political parties and the evolution of its party system. In particular, we are interested in exploring two inter-related aspects: frst, what is the role of patronage for party organisations in Portugal? And second, how does it im- pact on intra-party functioning? Overall, access to state resources appears to be cru- cial in the rapid building of the party organisations and in their subsequent mainte- nance, potentially creating also barriers to entry for new competitors. This pattern is to a large extent explained by the context in which parties emerged in Portugal, which substantially shaped their organisational structure and societal roots. Keywords: Party; Patronage; Appointments; Portugal. -

Open in PDF Format

Biographies of eminent Portuguese politicians (names from A to L) Source: Maria Fernanda Rollo, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas, Av. de Berna, 26-C 1069-061 Lisboa. www.fcsh.unl.pt. Copyright: (c) Translation CVCE.EU by UNI.LU All rights of reproduction, of public communication, of adaptation, of distribution or of dissemination via Internet, internal network or any other means are strictly reserved in all countries. Consult the legal notice and the terms and conditions of use regarding this site. URL: http://www.cvce.eu/obj/biographies_of_eminent_portuguese_politicians_names_fro m_a_to_l-en-d7ef7c24-0423-403d-9e47-792b27cf5ec3.html Last updated: 05/07/2016 1/20 Biographies of eminent Portuguese politicians (names from A to L) ABREU, Augusto Cancela de Director of Sociedade Estoril and a member of the Board of Directors of Caminhos-de-ferro da Beira Alta. In the government reshuffle of 6 September 1944, became Minister for Public Works, a post which he held until 4 February 1947. Then moved to the Ministry of Home Affairs as Minister until 2 August 1950. ALMEIDA, Vasco Vieira de Born in 1932. Graduated in law in 1955. Member of MUD Juvenil (MUD-J) [youth wing of the Movement of Democratic Unity] when in grammar school. Supported Arlindo Vicente as a candidate for President of the Republic in the 1958 elections, transferring his support to Humberto Delgado when the PCP’s candidate announced that he would stand down. Was imprisoned twice: in 1958, on the day of the presidential elections, and in 1963, after being involved in the escape of some important Communist Party members from Caxias prison on 4 December 1961. -

The Transition to a Democratic Portuguese Judicial System: (Delaying) Changes in the Legal Culture*

International Journal of Law in Context, 12,1 pp. 24–41 (2016) © Cambridge University Press 2016 doi:10.1017/S1744552315000373 The transition to a democratic Portuguese judicial system: (delaying) changes in the legal culture* † João Paulo Dias Abstract The Revolution of 25 April 1974 had a strong impact on justice in Portugal. Initially, it can be said that there was evidence of a process of democratisation involving the judicial structures, together with effective improvements to conditions allowing for independent and autonomous professional performance. However, in analysing the course of judicial reforms, it can be seen that changes took place more on a legislative level than in terms of the performance of the courts, proving that the evolution of the judicial system still demands a change of the legal culture. Therefore, the objective of this paper is to reflect on the evolution of the legal architecture in Portugal, seeking to determine whether the transition to a democratic judicial system is complete or whether, on the contrary, we are still faced with the process of justice in transition, delaying any changes in the current legal culture. I. Justice(s), democratisation, protagonists and social change: forty years after the Revolution The analysis of democratisation processes in various countries that have experienced dictatorships, such as Spain, Greece, Portugal or, more recently, Eastern and Central European countries, ‘tends to present the construction of an independent judiciary either as an automatic consequence of the institutionalisation of democracy, or as one of the ceteris paribus conditions under which the behaviour of political actors unfolds’ (Magalhães, 1995, p. -

Redalyc.Weak Societal Roots, Strong Individual Patrons? Patronage & Party Organization in Portugal

Revista Enfoques: Ciencia Política y Administración Pública ISSN: 0718-0241 [email protected] Universidad Central de Chile Chile Jalali, Carlos; Lisi, Marco Weak Societal Roots, Strong Individual Patrons? Patronage & Party Organization in Portugal Revista Enfoques: Ciencia Política y Administración Pública, vol. VII, núm. 11, 2009, pp. 441-470 Universidad Central de Chile Santiago, Chile Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=96011647014 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Revista Enfoques, Vol. VII N° 11, 2009 pp. 441/470 Weak Societal Roots, Strong Individual Patrons? Patronage & Party Organization in Portugal Carlos Jalali - [email protected] Universidade de Aveiro, Portugal Marco Lisi - [email protected] Instituto de Ciências Sociais - Universidade de Lisboa, Portugal We examine why patronage may constitute an important dimension of analysis in the study of Portuguese political parties and the evolution of its party system. In particular, we are interested in exploring two inter-related aspects: first, what is the role of patronage for party organisations in Portugal? And second, how does it im- pact on intra-party functioning? Overall, access to state resources appears to be cru- cial in the rapid building of the party organisations and in their subsequent mainte- nance, potentially creating also barriers to entry for new competitors. This pattern is to a large extent explained by the context in which parties emerged in Portugal, which substantially shaped their organisational structure and societal roots.