Saving Global Nature: Greening UK Official Development Assistance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trustee Report and Financial Statements 2011/12

Trustee Report and Financial Statements 2011/12 Company number 5042279 Paul Hamlyn Foundation Trustee Report and Financial Statements 2011/12 1 Contents Paul Hamlyn Foundation 2 Chair’s statement 4 Director’s report 6 Arts programme 8 Education and Learning programme 13 Social Justice programme 20 India programme 25 Other grants 26 Evaluation report 28 Reference and administrative details and audit report 31 List of grants awarded in 2011/12 36 Financial review 53 Statement of Financial Activities, Balance Sheet and Cashflow Statement 57 Notes to the financial statements 60 Trustees, staff and advisors 70 2 Paul Hamlyn Foundation Trustee Report and Financial Statements 2011/12 Paul Hamlyn Foundation Paul Hamlyn was an entrepreneur, publisher and philanthropist, committed to providing new opportunities and experiences for people regardless of their background. From the outset, his overriding concern was to open up the arts and education to everyone, but particularly to young people. In 1987, he established the Paul Hamlyn Foundation for general charitable purposes. Since then, we have continuously supported charitable activity in the areas of the arts, education and learning and social justice in the UK, enabling individuals, especially children and young people, to experience a better quality of life. We also support local charities in India that help the poorest communities in that country gain access to basic services. Paul Hamlyn died in August 2001, but the magnificent bequest of most of his estate to the Foundation enabled us to build on our past approaches. Mission To maximise opportunities for individuals and communities to realise their potential and to experience and enjoy a better quality of life, now and in the future. -

Download Publication

CONTENTS History The Council is appointed by the Muster for Staff The Arts Council of Great Britain wa s the Arts and its Chairman and 19 othe r Chairman's Introduction formed in August 1946 to continue i n unpaid members serve as individuals, not Secretary-General's Prefac e peacetime the work begun with Government representatives of particular interests o r Highlights of the Year support by the Council for the organisations. The Vice-Chairman is Activity Review s Encouragement of Music and the Arts. The appointed by the Council from among its Arts Council operates under a Royal members and with the Minister's approval . Departmental Report s Charter, granted in 1967 in which its objects The Chairman serves for a period of five Scotland are stated as years and members are appointed initially Wales for four years. South Bank (a) to develop and improve the knowledge , Organisational Review understanding and practice of the arts , Sir William Rees-Mogg Chairman Council (b) to increase the accessibility of the art s Sir Kenneth Cork GBE Vice-Chairma n Advisory Structure to the public throughout Great Britain . Michael Clarke Annual Account s John Cornwell to advise and co-operate wit h Funds, Exhibitions, Schemes and Awards (c) Ronald Grierson departments of Government, local Jeremy Hardie CB E authorities and other bodies . Pamela, Lady Harlec h Gavin Jantje s The Arts Council, as a publicly accountable Philip Jones CB E body, publishes an Annual Report to provide Gavin Laird Parliament and the general public with an James Logan overview of the year's work and to record al l Clare Mullholland grants and guarantees offered in support of Colin Near s the arts. -

Bradmore Lunches

ABBOTT William Abbot of Bradmore received lease from Sir John Willughby 30.6.1543. Robert Abbot married Alice Smyth of Bunny at Bunny 5.10.1566. Henry Sacheverell of Ratcliffe on Soar, Geoffrey Whalley of Idersay Derbyshire, William Hydes of Ruddington, Robert Abbotte of Bradmore, John Scotte the elder, son and heir of late Henry Scotte of Bradmore, and John Scotte the younger, son and heir of Richard Scotte of Bradmore agree 7.1.1567 to levy fine of lands, tenements and hereditaments in Bradmore, Ruddington and Cortlingstocke to William Kinder and Richard Lane, all lands, tenements and hereditaments in Bradmore to the sole use of Geoffrey Walley, and in Ruddington and 1 cottage and land in Bradmore to the use of Robert Abbotte for life and after his death to Richard Hodge. Alice Abbott married Oliver Martin of Normanton at Bunny 1.7.1570. James Abbot of Bradmore 20.10.1573, counterpart lease from Frauncis Willughby Ann Abbott married Robert Dawson of Bunny at Bunny 25.10.1588. Robert Abbot, of Bradmore? married Dorothy Walley of Bradmore at Bunny 5.10.1589. Margery Abbott married Jarvis Hall/Hardall of Ruddington at Bunny 28.11.1596. William Abbot of Bradmore, husbandman, married Jane Barker of Bradmore, widow, at Bunny 27.1.1600, licence issued 19.1.1600. 13.1.1613 John Barker of Newark on Trent, innholder, sold to Sir George Parkyns of Bunny knight and his heirs 1 messuage or tenement in Bradmere now or late in the occupation of William Abbott and Jane his wife; John Barker and his wife Johane covenant to acknowledge a fine of the premises within 7 years. -

Linear Film 114 - Online Space 118

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details !1 THIS IS NOT US: Performance, Relationships and Shame in Documentary Filmmaking Daisy Asquith PhD CREATIVE & CRITICAL PRACTICE University of Sussex, June 2018 WORD COUNT: 40,072 PRACTICE ONLINE: https://daisy-asquith-xdrf.squarespace.com/home/ !2 Summary This thesis investigates performance, identity, representation and shame in documentary flmmaking. Identities that are performed and mediated through a relationship between flmmaker and participant are examined with detailed reference to two decades of my own practice. A refexive, feminist approach engages my own flms - and the relationships that produced them - in analysis of the ethical potholes and emotional challenges in representing others on TV. The trigger for this research was the furiously angry reaction of the One Direction fandom to my representation of them in Crazy About One Direction (Channel 4, 2013). This offered an opportunity to investigate the potential for shame in documentary; a loud and clear case study of flmed participants using social media to contest their image on screen. -

Download Publication

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This research has been a lengthy and complex process. We have always stated publicly that this work was for the dance field and it has been carried out in collaboration with the field. We have had support from so many people throughout the process and without this we could not have completed the work. Firstly, we would like to thank Janet Archer, Theresa Beattie, Ellie Hartwell and Tania Wilmer in the dance strategy department of Arts Council England. Without their support this work would not have been possible. Tania Wilmer carried out many of the interviews for the illustrations that pepper the report and we are immensely grateful to her for her rigour and hard work. We are also grateful to those who agreed to be interviewed and gave so generously of their time. There were many Arts Council staff who sourced and contributed data but Jonathan Treadway, Amanda Rigali, Delia Barker and Rebecca Dawson deserve special mention. Regional dance officers provided valuable local data and information and their input through the Dance Practice Group meetings was always valuable. Terry Adams and Claire Cowles (the ‘Survey Monkey’ queen) provided invaluable research backup to us throughout the process and their rigour is evident in the survey data as well as in the analysis of the Arts Council England data. The Steering Group (listed in Appendix One) supported the process, guided us wisely and challenged us when necessary. Their support for the consultation events was also greatly valued. The strategic agencies provided ongoing access to data, Foundation for Community Dance (FCD) staff carried out an analysis of jobs advertised and Sean Williams and his team at Council for Dance Education and Training (CDET) carried out research on the private sector for us that has helped to create a better picture of this sector. -

News & Information from Southwell Minster

December 2019/January 2020 £2.50 News & Information from Southwell Minster Follow us on twitter @SouthwMinster www.southwellminster.org Contents… At a Glance … Welcome 3 The full list of services is on the What’s On pages at the centre of the magazine. Pause for Thought 3 Worship: not just for Christmas 4 December Green and eco friendly Christmas tips 4 Sunday 1 Usual morning services, 8.00, 9.30, 11.15am Advent Sunday 6.30pm Advent Procession Refugees in Nottingham 5 Friday 6 12.15pm Concert: Britten’s Ceremony of Carols From the Registers 5 7.00pm Framework Carol Service Saturday 7 7.30pm Concert: Cantamus Girls’ Choir Newwark Foodbank 6/7 Monday 9 5.30pm Festal Evensong for Blessed Virgin Mary Education News 7 7.00pm Reach Learning Disability service Christmas comes but once a year? 8 Tuesday 10 7.30pm Beaumond House ‘Light up a Life’ service Wednesday 11 7.00pm Emergency Services Carol Service Nativity or Presepe—the Italian connection 9 Thursday 12 7.30pm Concert: Handel’s Messiah Bethlehem 10 Saturday 14 7.30pm ‘Carols for Everyone’ The story of In the Bleak Midwinter 11 Sunday 15 5.00pm Christingle Service 7.30pm Carols in the Great Hall Notes from Chapter 12 Monday 16 7.00pm Concert: Minster School What’s On 13-16 Tuesday 17 7.00pm Concert: G4 (sold out) News from our Mission Partners 16 Friday 20 7.30pm Concert: Southwell Music Festival Christmas through the ages 17 Sunday 22 6.30pm Organ Meditation: Messaien’s Nativité Monday 23 7.00pm Cathedral Carol Service News from Framework 18 Tuesday 24 11.00am and 2.00pm Crib Services -

The Elephant Times Tide~ On-Line Magazine

The Elephant Times Tide~ on-line magazine Issue Five: The AGM Issue MAY 2021 Building a network Making connections Back to contents Tide~ on line magazine Tide~ Teachers in development education 1 Tide~ publications are now available for free Welcome to Elephant Times 5 WWW You are welcome to adapt them for your teaching. This magazine enriches the Tide~ website by seeking fresh dialogue and They represent the contribution of thousands of teachers over the ways to re-establish the creativity of a Tide~ teacher network. years and hundreds of teachers that have taken lead roles in both This AGM issue takes stock of the first year ... and looks to the future. curriculum projects and study visits. Covid 19 is inhibiting plans but a number of projects are shaping up. Note: Copyright remains with Tide~ and should be acknowledged. CONTENTS First AGM of the new Tide~ network - Where are we going? 4 Commonwealth in town - an opportunity for learning? 8 _________________________ Seeking expressions of interest The first AGM of the new Tide~ Network will be ET Ubuntu Project with University of Worcester 12 Visions of education responding to the challenges of an uncertain future on Zoom at 7.30 on Thursday 17th June 2021 How to stay sane in an age of division ~ a conversation 14 The stimulus of Elif Shafak’s book >> Sign up to receive Zoom Link Connecting Dialogues - a new core framework for Tide~? 20 Seeking expressions of interest Mali revisited ~ Where camels are better than cars 24 _________________________ Sarah Snyder reflects on experience in Mali and her work now Bridging gaps and building wisdom 30 Harriet Marshall reflects on ET2 and poses challenges for the future To go to article click on titles click go to article To The Elephant Times is edited by Jeff Serf and Scott Sinclair. -

Churchyard Inscriptions

Churchyard Inscriptions Prior to 1999, no accurate plan of Bunny Churchyard was known to exist. The Index of Memorial Inscriptions recorded by Nottinghamshire Family History Society in 1984 was used as a basis for the study and the Churchyard was accurately surveyed during 1999. A few gravestones were missed in the 1984 survey, including that of Mary Champin who died in 1702 (the earliest so far discovered.) The latest gravestone recorded in the work is dated 1984. Against each located grave in the INDEX OF GRAVES is a co-ordinate reference to the CHURCHYARD PLAN, consisting of four figures. The first two indicate the row number in which the grave is to be found and the last two figures indicate its position in that row. Unfortunately the Churchyard plan is not yet available in an electronic form, although it is hoped a copy will be placed within Bunny Church soon. It is also hoped that we will be able to produce a simplified version of the plan to be made available online later in 2009. On the CHURCHYARD PLAN each grave is marked with the name and year of the most recent burial therein. Only the first six letters of the surname and the year are given so as to avoid a cramped notation but this is sufficient to identify the entry in the INDEX. Thus the CHURCHYARD PLAN indicates when the grave was last used. The INDEX, and the CHURCHYARD PLAN, are records of interments marked by a gravestone and the entries should match those in the Register of Burials for Bunny and Bradmore. -

D Asquith Phd FINAL Pages

!1 THIS IS NOT US: Performance, Relationships and Shame in Documentary Filmmaking Daisy Asquith PhD CREATIVE & CRITICAL PRACTICE University of Sussex, June 2018 WORD COUNT: 35.842 PRACTICE ONLINE: https://daisy-asquith-xdrf.squarespace.com/flms/ !2 Summary This thesis investigates performance, identity, representation and shame in documentary flmmaking. Identities that are performed and mediated through a relationship between flmmaker and participant are examined with detailed reference to two decades of my own practice. A refexive, feminist approach engages my own flms - and the relationships that produced them - in analysis of the ethical potholes and emotional challenges in representing others on TV. The trigger for this research was the furiously angry reaction of the One Direction fandom to my representation of them in Crazy About One Direction (Channel 4, 2013). This offered an opportunity to investigate the potential for shame in documentary; a loud and clear case study of flmed participants using social media to contest their image on screen. In the space between documentary confession and the reception of a story by the audience, a dangerous moment comes, in which shame can be received, perceived, projected, internalised or imagined. The point of this research is to offer to existing documentary theory a practitioner’s understanding of the processes which produce shame and to establish for documentary flmmakers some practical ways to resist and prepare against the rupture in identity that representation can cause those they flm. Engaging both theory and practice in pursuit of the same research questions, I make a self-refexive investigation into the ethics, affect and impact of representing others, employing the mediums and methods of fans to answer their complaints. -

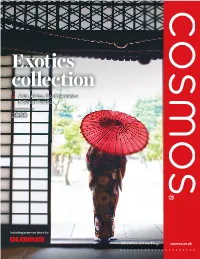

Exotics Collection 2020

Exotics collection Asia, Africa, South America & South Pacific 2020 Including premium tours by cosmos.co.uk “The big wide world suddenly seemed a bit smaller.” No one turns dream trips into reality with more expertise and affordability than Cosmos. With more than 50 years of sharing the world with value-minded travellers like you, we’ll help you turn your bucket list into a “better-than-I-dreamed” list. From the Amazon River to the Americana of Route 66; from the Australian Outback to the Inside Passage of Alaska, there’s no end to the ways you can make your travel dreams come true. Whether you’re wishing for a walk through the temples of Thailand or the plains of Serengeti, we take you to the world’s most amazing places. 2 Dreams meet Doable With more than 50 years of sharing the world with Director; guided sightseeing of must-see sights; and savvy travellers who answer adventure’s call, we seamless transportation that makes getting there know why you travel. We know that another day in half the fun! From Alaska to Australia, and almost an amazing destination means more to you than every place in between, our expertly planned, easy- a fancy chocolate on your pillow! Cosmos travel to-afford, and even easier-to-enjoy holidays turn experts still insist that you enjoy comfortable, “wish I could” into “glad I did.” Go ahead, open the clean, and attractive hotels; a professional Tour door when adventure knocks! Introduction to Cosmos .................................................................................................................................4 Know before you go ...................................................................................................................................111 Introduction to Globus ............................................................................................................................... -

Yearbook 2006/07

1488 PHF Yearbook cover AW 2 3/8/07 11:03 Page 1 Yearbook 2006/07 Paul Hamlyn Foundation 18 Queen Anne’s Gate London SW1H 9AA Tel: 020 7227 3500 Fax: 020 7222 0601 Email: [email protected] www.phf.org.uk Registered charity number 1102927 1488 PHF Yearbook cover AW 2 3/8/07 11:03 Page 2 Paul Hamlyn Foundation Trustees, staff and advisers Paul Hamlyn was an entrepreneur, publisher Strategic aims Trustees Jane Hamlyn (Chair) and philanthropist, committed to providing Our strategic aims for the six years 2006-2012 are: Rushanara Ali new opportunities and experiences for Bob Boas 1. Enabling people to experience and enjoy the arts. Michael Hamlyn people regardless of their background. James Lingwood From the outset his overriding concern 2. Developing people’s education and learning. Estelle Morris Lord Moser (from September 2006) was to open up the arts and education to 3. Integrating marginalised young people who are at times Anthony Salz everyone, but particularly to young people. of transition. Peter Wilson-Smith In 1987 he established the Paul Hamlyn In addition, we have three related aims: Staff Foundation for general charitable purposes. Denise Barrows Education and Learning Programme Manager (from May 2007) 4. Advancing through research the understanding of the Susan Blishen Social Justice Programme Manager Since then we have continuously supported charitable relationships between the arts, education and learning Régis Cochefert Arts Programme Manager Gerry Creedon Accountant activity in the areas of the arts, education and learning and and social change. social justice in the UK, enabling individuals, especially Sarah Jane Dooley Grants Officer (from December 2006) 5. -

Carlo-Schmid-Programm

Carlo-Schmid-Programm für Praktika in Internationalen Organisationen und EU-Institutionen Praktikumsangebote Programmlinie B Ausschreibung 2020/2021 Stand: Dezember 2019 Inhaltsverzeichnis Referenz-Nr. Sitz Land Schlagwort Stud. Grad. Stud. Grad. A BA B MA MA BIM Wien Österreich Human Dignity and Public Security Department - x x x EBRD1 London Vereinigtes Taskforce for Climate Financial Disclosure - x x x Königreich EBRD2 London Vereinigtes Economic Research - - x x Königreich EBRD3 London Vereinigtes SME Finance & Development HQ Team - x - x Königreich EBRD4 London Vereinigtes Economics, Policy and Governance Department - x - - Königreich EUDEL Genf Schweiz Political Press and Communication Section - - x x FAO1 Rom Italien Agricultural Extension and Rural Advisory Services - - x x FAO2 Rom Italien Technologies and Practices for Small Agricultural Producers - x x x Team FAO-UNECE1 Genf Schweiz Environmental and Forestry Communication - x x x FAO-UNECE2 Genf Schweiz Forest Products and Circular Economy - x x x GGKP-UNEP Genf Schweiz Green Growth Knowledge Platform - - x x ICC Den Haag Niederlande Trial Division - - - x ICMPD Brüssel Belgien Policy and Strategic Partnership Unit - x x x IFC1 Washington DC USA Municipal and Environmental Infrastructure Department - - x x IFC2 Washington DC, USA/Vietnam/ Economics & Private Sector Development - - - x Hanoi or Nairobi Kenia IISD Genf Schweiz The Global Subsidies Initiative - x x x INTERPEACE Abidjan Côte d'Ivoire Peacebuilding Project Management - - - x IOM1 Genf Schweiz Border & Identity