Ovid Transformed: the Dynamics of Sexual Positioning in Titian’S Poesie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

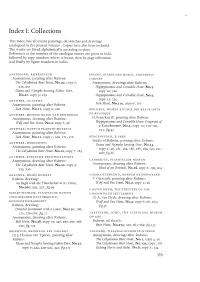

Index I: Collections

Index I: Collections This index lists ail extant paintings, oil sketches and drawings catalogued in the present volume . Copies have also been included. The works are listed alphabetically according to place. References to the number of the catalogue entries are given in bold, followed by copy numbers where relevant, then by page references and finally by figure numbers in italics. AMSTERDAM, RIJKSMUSEUM BRUGES, STEDEEÏJKE MUSEA, STEINMETZ- Anonymous, painting after Rubens : CABINET The Calydonian Boar Hunt, N o .20, copy 6; Anonymous, drawings after Rubens: 235, 237 Hippopotamus and Crocodile Hunt, N o .5, Diana and Nymphs hanting Fallow Deer, copy 12; 120 N o.21, copy 5; 239 Hippopotamus and Crocodile Hunt, N o .5, cop y 13; 120 ANTWERP, ACADEMY Anonymous, painting after Rubens: Lion Hunt, N o.ne, copy 6; 177 Lion Hunt, N o.11, copy 2; 162 BRUSSELS, MUSÉES ROYAUX DES BEAUX-ARTS DE BELGIQUE ANTWERP, MUSEUM MAYER VAN DEN BERGH Anonymous, drawing after Rubens: H.Francken II, painting after Rubens: Hippopotamus and Crocodile Hunt: Fragment of W olf and Fox Hunt, N o .2, copy 7; 96 a Kunstkammer, N o.5, copy 10; 119-120, ANTW ERP, MUSEUM PLANTIN-M O RETUS 123 ;fig .4S Anonymous, painting after Rubens: Lion Hunt, N o .n , copy 1; 162, 171, 178 BÜRGENSTOCK, F. FREY Studio of Rubens, painting after Rubens: ANTWERP, RUBENSHUIS Diana and Nymphs hunting Deer, N o .13, Anonymous, painting after Rubens : copy 2; 46, 181, 182, 186, 188, 189, 190, 191, The Calydonian Boar Hunt, N o .12, copy 7; 185 208; fig.S6 ANTWERP, STEDELIJK PRENTENKABINET Anonymous, -

The Great Apostasy

The Great Apostasy R. J. M. I. By The Precious Blood of Jesus Christ; The Grace of the God of the Holy Catholic Church; The Mediation of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Our Lady of Good Counsel and Crusher of Heretics; The Protection of Saint Joseph, Patriarch of the Holy Family and Patron of the Holy Catholic Church; The Guidance of the Good Saint Anne, Mother of Mary and Grandmother of God; The Intercession of the Archangels Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael; The Intercession of All the Other Angels and Saints; and the Cooperation of Richard Joseph Michael Ibranyi To Jesus through Mary Júdica me, Deus, et discérne causam meam de gente non sancta: ab hómine iníquo, et dolóso érue me Ad Majorem Dei Gloriam 2 “I saw under the sun in the place of judgment wickedness, and in the place of justice iniquity.” (Ecclesiastes 3:16) “Woe to you, apostate children, saith the Lord, that you would take counsel, and not of me: and would begin a web, and not by my spirit, that you might add sin upon sin… Cry, cease not, lift up thy voice like a trumpet, and shew my people their wicked doings and the house of Jacob their sins… How is the faithful city, that was full of judgment, become a harlot?” (Isaias 30:1; 58:1; 1:21) “Therefore thus saith the Lord: Ask among the nations: Who hath heard such horrible things, as the virgin of Israel hath done to excess? My people have forgotten me, sacrificing in vain and stumbling in their way in ancient paths.” (Jeremias 18:13, 15) “And the word of the Lord came to me, saying: Son of man, say to her: Thou art a land that is unclean, and not rained upon in the day of wrath. -

Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected]

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2016 Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Van Oort, Danielle, "Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal" (2016). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 1016. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. REST, SWEET NYMPHS: PASTORAL ORIGINS OF THE ENGLISH MADRIGAL A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music Music History and Literature by Danielle Van Oort Approved by Dr. Vicki Stroeher, Committee Chairperson Dr. Ann Bingham Dr. Terry Dean, Indiana State University Marshall University May 2016 APPROVAL OF THESIS We, the faculty supervising the work of Danielle Van Oort, affirm that the thesis, Rest Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal, meets the high academic standards for original scholarship and creative work established by the School of Music and Theatre and the College of Arts and Media. This work also conforms to the editorial standards of our discipline and the Graduate College of Marshall University. With our signatures, we approve the manuscript for publication. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to express appreciation and gratitude to the faculty and staff of Marshall University’s School of Music and Theatre for their continued support. -

A Guide to Post-Classical Works of Art, Literature, and Music Based on Myths of the Greeks and Romans

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 112 438 CS 202 298 AUTHOR Smith, Ron TITLE A Guide to Post-Classical Works of Art, Literature, and Music Based on Myths of the Greeks and Romans. PUB DATE 75 NOTE 40p.; Prepared at Utah State University; Not available in hard copy due to marginal legibility of original document !DRS PRICE MF-$0.76 Plus Postage. HC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Art; *Bibliographies; Greek Literature; Higher Education; Latin Literature; *Literature; Literature Guides; *Music; *Mythology ABSTRACT The approximately 650 works listed in this guide have as their focus the myths cf the Greeks and Romans. Titles were chosen as being (1)interesting treatments of the subject matter, (2) representative of a variety of types, styles, and time periods, and (3) available in some way. Entries are listed in one of four categories - -art, literature, music, and bibliography of secondary sources--and an introduction to the guide provides information on the use and organization of the guide.(JM) *********************************************************************** Documents acquired by ERIC include many informal unpublished * materials not available from other sources. ERIC makes every effort * * to obtain the best copy available. Nevertheless, items of marginal * * reproducibility are often encountered and this affects the quality * * of the microfiche and hardcopy reproductions ERIC makes available * * via the ERIC Document Reproduction Service (EDRS). EDRS is not * responsible for the quality of the original document. Reproductions * * supplied -

Between Arcadia and Crete: Callisto in Callimachus' Hymn to Zeus The

Between Arcadia and Crete: Callisto in Callimachus’ Hymn to Zeus The speaker of Callimachus’ Hymn to Zeus famously asks Zeus himself whether he should celebrate the god as “Dictaean,” i.e. born on Mt. Dicte in Crete, or “Lycaean,” born on Arcadian Mt. Lycaeus (4-7). When the response comes, “Κρῆτες ἀεὶ ψεῦσται” (“Cretans are always liars,” 8), the hymnist agrees, and for support recalls that the Cretans built a tomb for Zeus, who is immortal (8-9). In so dismissing Cretan claims to truth, the hymnist justifies an Arcadian setting for his ensuing birth narrative (10-41). Curiously, however, after recounting Zeus’s birth and bath, the hymnist suddenly locates the remainder of the god’s early life in Crete after all (42-54). The transition is surprising, not only because it runs counter to the previous rejection of Cretan claims, but also because the Arcadians themselves held that Zeus was both born and raised in Arcadia (Paus. 8.38.2). While scholars have focused on how the ambiguity of two place names (κευθμὸν... Κρηταῖον, 34; Θενάς/Θεναί, 42, 43) misleads the audience and/or prepares them for the abrupt move from Arcadia to Crete (Griffiths 1970 32-33; Arnott 1976 13-18; McLennan 1977 66, 74- 75; Tandy 1979 105, 115-118; Hopkinson 1988 126-127), this paper proposes that the final word of the birth narrative, ἄρκτοιο (“bear,” 41), plays an important role in the transition as well. This reference to Callisto a) allusively justifies the departure from Arcadia, by suggesting that the Arcadians are liars not unlike the Cretans; b) prepares for the hymnist’s rejection of the Cretan account of Helice; and c) initiates a series of heavenly ascents that binds the Arcadian and Cretan portions of the hymn and culminates climactically with Zeus’s own accession to the sky. -

Beaumont Art League Summer Activities

A View From The Top Greg Busceme, TASI Director THIS IS OUR SUMMER ISSUE which is fol- 50 organizations receive a $1,000 grant. lowed by two months of limited communi- We are grateful for The Stark cation by mail or print. Foundation’s contribution to The Art This is partially by design and partial- Studio. The funds will go to rebuilding our ly by necessity to give us a chance to security fence around the Studio yard and recover from our printing and mailing improving our parking arrangements — Vol. 17, No. 9 ISSUE costs for monthly invitations and newspa- an integral part of an ongoing project to pers. Printing costs alone average about revitalize our facility as we recover fully Publisher . The Art Studio, Inc. $580 a month. from the storms. We already have part- Editor . Andy Coughlan This is not just to whine but to let ners in this project beginning with Boy Copy Editor . Tracy Danna everyone know we are getting serious Scout Eagle candidate Brandon Cate. In Contributing Writers . Elena Ivanova about membership renewals and new pursuit of being an Eagle Scout, Brandon Distribution Volunteer . Elizabeth Pearson members. For the first time, we can only has taken on the task of striping our new send exhibition announcements and parking area for improved space and a The Art Studio, Inc. Board of Directors ISSUE to members in good standing. safer environment. On our part, we will We hope those non-members who use the Stark funds to get the material President Ex-Officio . Greg Busceme have been enjoying our mailings remem- necessary to put up a fence on the front of Vice-President. -

Review of the Year 2012–2013

review of the year TH E April 2012 – March 2013 NATIONAL GALLEY TH E NATIONAL GALLEY review of the year April 2012 – March 2013 published by order of the trustees of the national gallery london 2013 Contents Introduction 5 Director’s Foreword 6 Acquisitions 10 Loans 30 Conservation 36 Framing 40 Exhibitions 56 Education 57 Scientific Research 62 Research and Publications 66 Private Support of the Gallery 70 Trustees and Committees of the National Gallery Board 74 Financial Information 74 National Gallery Company Ltd 76 Fur in Renaissance Paintings 78 For a full list of loans, staff publications and external commitments between April 2012 and March 2013, see www.nationalgallery.org.uk/about-us/organisation/ annual-review the national gallery review of the year 2012– 2013 introduction The acquisitions made by the National Gallery Lucian Freud in the last years of his life expressed during this year have been outstanding in quality the hope that his great painting by Corot would and so numerous that this Review, which provides hang here, as a way of thanking Britain for the a record of each one, is of unusual length. Most refuge it provided for his family when it fled from come from the collection of Sir Denis Mahon to Vienna in the 1930s. We are grateful to the Secretary whom tribute was paid in last year’s Review, and of State for ensuring that it is indeed now on display have been on loan for many years and thus have in the National Gallery and also for her support for very long been thought of as part of the National the introduction in 2012 of a new Cultural Gifts Gallery Collection – Sir Denis himself always Scheme, which will encourage lifetime gifts of thought of them in this way. -

Rethinking Savoldo's Magdalenes

Rethinking Savoldo’s Magdalenes: A “Muddle of the Maries”?1 Charlotte Nichols The luminously veiled women in Giovanni Gerolamo Savoldo’s four Magdalene paintings—one of which resides at the Getty Museum—have consistently been identified by scholars as Mary Magdalene near Christ’s tomb on Easter morning. Yet these physically and emotionally self- contained figures are atypical representations of her in the early Cinquecento, when she is most often seen either as an exuberant observer of the Resurrection in scenes of the Noli me tangere or as a worldly penitent in half-length. A reconsideration of the pictures in connection with myriad early Christian, Byzantine, and Italian accounts of the Passion and devotional imagery suggests that Savoldo responded in an inventive way to a millennium-old discussion about the roles of the Virgin Mary and Mary Magdalene as the first witnesses of the risen Christ. The design, color, and positioning of the veil, which dominates the painted surface of the respective Magdalenes, encode layers of meaning explicated by textual and visual comparison; taken together they allow an alternate Marian interpretation of the presumed Magdalene figure’s biblical identity. At the expense of iconic clarity, the painter whom Giorgio Vasari described as “capriccioso e sofistico” appears to have created a multivalent image precisely in order to communicate the conflicting accounts in sacred and hagiographic texts, as well as the intellectual appeal of deliberately ambiguous, at times aporetic subject matter to northern Italian patrons in the sixteenth century.2 The Magdalenes: description, provenance, and subject The format of Savoldo’s Magdalenes is arresting, dominated by a silken waterfall of fabric that communicates both protective enclosure and luxuriant tactility (Figs. -

Julius S. Held Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3g50355c No online items Finding aid for the Julius S. Held papers, ca. 1921-1999 Isabella Zuralski. Finding aid for the Julius S. Held 990056 1 papers, ca. 1921-1999 Descriptive Summary Title: Julius S. Held papers Date (inclusive): ca. 1918-1999 Number: 990056 Creator/Collector: Held, Julius S (Julius Samuel) Physical Description: 168 box(es)(ca. 70 lin. ft.) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: Research papers of Julius Samuel Held, American art historian renowned for his scholarship in 16th- and 17th-century Dutch and Flemish art, expert on Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. The ca. 70 linear feet of material, dating from the mid-1920s to 1999, includes correspondence, research material for Held's writings and his teaching and lecturing activities, with extensive travel notes. Well documented is Held's advisory role in building the collection of the Museo de Arte de Ponce in Puerto Rico. A significant portion of the ca. 29 linear feet of study photographs documents Flemish and Dutch artists from the 15th to the 17th century. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English Biographical / Historical Note The art historian Julius Samuel Held is considered one of the foremost authorities on the works of Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. -

Classical Studies 2012 Contents Highlights

Classical Studies 2012 www.cambridge.org/classics Contents Highlights Classical studies (general)the archimedes palimpsest publications1 the archimedes palimpsest publications The and wilson tchernetska, netz, noel, reViel NetZ is Professor of classics and Professor of Philos- the Archimedes Palimpsest is the name given to a Byzantine coNteNts ophy, by courtesy, at stanford university. his books from cambridge Classical languages 4 VANDENHOUT university Press include The Shaping of Deduction in Greek Math- prayer book that was written over a number of earlier manuscripts, introduction: the Archimedes Palimpsest Project Hittite is the earliest attested Indo-European language and was the ematics: A Study in Cognitive History (1999, runciman Award), The Archimedes william noel including one that contained two unique works by Archimedes, Transformation of Early Mediterranean Mathematics: From Problems language of a state which flourished in Asia Minor in the second PArt 1 the mANuscriPts to Equations (2004), and Ludic Proof: Greek Mathematics and the unquestionably the greatest mathematician of antiquity. sold at THE Alexandrian Aesthetic (2009). he is also the author of a multi-volume millennium BC. This exciting and accessible new introductory course, euchologion translation of and commentary on the works of Archimedes, also auction in 1998, it has since been the subject of a privately funded Archimedes: treatises (codex c) with cambridge, the first volume of which, The Two Books On the PwhichA canlim be used in both trimesterP sestand semester -

Homer and Hesiod, Which Ovid Appropriates

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 14 August 2018 Version of attached le: Published Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Ziogas, I. (2018) 'Ovid's Hesiodic voices.', in Oxford handbook to Hesiod. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 377-393. Further information on publisher's website: https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190209032.013.48 Publisher's copyright statement: Ziogas, Ioannis. Ovid's Hesiodic voices. In The Oxford Handbook of Hesiod. Oxford University Press, August 08, 2018. Oxford Handbooks Online, reproduced by permission of Oxford University Press https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190209032.013.48 Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk Ovid’s Hesiodic Voices Oxford Handbooks Online Ovid’s Hesiodic Voices Ioannis Ziogas The Oxford Handbook of Hesiod Edited by Alexander C. Loney and Stephen Scully Print Publication Date: Sep 2018 Subject: Classical Studies, Classical Poetry Online Publication Date: Aug 2018 DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190209032.013.48 Abstract and Keywords Ovid’s poetry opens a dialogue with the three major Hesiodic works: the Theogony, the Works and Days, and the Catalogue of Women. -

Scultore Emiliano Emilia (Italy) Last Decades of 18Th Century Saint Anthony the Abbot Sant’Antonio Abate

2 Caiati & Gallo 4 Caiati & Gallo Caiati & Gallo Milan, Via Gesù, 17 9 October - 8 November 2014 Monday - Saturday 10 am / 1 pm - 2 / 7 pm Contributions by: Alicia Adamczak Charles Avery Andrea Bacchi Sandro Bellesi Giorgio Bonsanti Marcello De Grassi Léon Lock Silvia Massari Fernando Mazzocca Susanna Zanuso Aknowledgements: Accademia di Belle Arti di Bologna, Associazione Antiquari d’Italia, Axa Arte - Italia, Carina Branzei, Francesco Calandra, Italo Carli, Arturo De Angeli, Alessandro Della Latta, Paolo Frassetto, F.C. studio Perotti, Milano, Saverio Fontini, Graziano Gallo, Jutta Kappel, Massimo Listri, Chiara Piani, Dagmar Preising, Arturo Sansoni, Frits Scholten, Christian Theuerkauff, Matthias Weniger Translations: Christian Bayliss, Serenella Castri e William George Glandon Exhibition Design Maestro Antonio Mastromattei Design and printing: Saverio Fontini - [email protected] © Partial or total reproduction for collective use of the present publication is strictly forbidden without the publisher’s specific authorization. Printed in Florence - Italy, September 2014 © Edizione Scribo srl - Firenze © Caiati & Gallo ISBN: 9788890652929 Caiati & Gallo Old Masters and Works of Art The Sparkling Soul of Terracotta Exhibition project devised from an idea of Roberto R.Caiati and Giorgio Gallo edited by Serenella Castri Via Gesù, 17 20121 Milan - Italy +39 02 794866 - +39 02 783863 www.caiatigallo.com - [email protected] Antonio Begarelli Modena, 1499 - 1565 Saint with book (St. Justine?) Santa con libro (santa Giustina?) Terracotta h. 96 cm (37 13/16 in.) Provenance Padua, private collection Antonio Begarelli, plasticatore in terracotta nel Cinquecento Antonio Begarelli, a terracotta sculptor in the sixteenth emiliano, nacque a Modena probabilmente nel 1499, figlio di century in Emilia, was born in Modena probably around un Giuliano “fornaciaio”.