Accumulation of PNPLA3 on Lipid Droplets Is the Basis of Associated Hepatic Steatosis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Metabolic Serine Hydrolases and Their Functions in Mammalian Physiology and Disease Jonathan Z

REVIEW pubs.acs.org/CR The Metabolic Serine Hydrolases and Their Functions in Mammalian Physiology and Disease Jonathan Z. Long* and Benjamin F. Cravatt* The Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology and Department of Chemical Physiology, The Scripps Research Institute, 10550 North Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla, California 92037, United States CONTENTS 2.4. Other Phospholipases 6034 1. Introduction 6023 2.4.1. LIPG (Endothelial Lipase) 6034 2. Small-Molecule Hydrolases 6023 2.4.2. PLA1A (Phosphatidylserine-Specific 2.1. Intracellular Neutral Lipases 6023 PLA1) 6035 2.1.1. LIPE (Hormone-Sensitive Lipase) 6024 2.4.3. LIPH and LIPI (Phosphatidic Acid-Specific 2.1.2. PNPLA2 (Adipose Triglyceride Lipase) 6024 PLA1R and β) 6035 2.1.3. MGLL (Monoacylglycerol Lipase) 6025 2.4.4. PLB1 (Phospholipase B) 6035 2.1.4. DAGLA and DAGLB (Diacylglycerol Lipase 2.4.5. DDHD1 and DDHD2 (DDHD Domain R and β) 6026 Containing 1 and 2) 6035 2.1.5. CES3 (Carboxylesterase 3) 6026 2.4.6. ABHD4 (Alpha/Beta Hydrolase Domain 2.1.6. AADACL1 (Arylacetamide Deacetylase-like 1) 6026 Containing 4) 6036 2.1.7. ABHD6 (Alpha/Beta Hydrolase Domain 2.5. Small-Molecule Amidases 6036 Containing 6) 6027 2.5.1. FAAH and FAAH2 (Fatty Acid Amide 2.1.8. ABHD12 (Alpha/Beta Hydrolase Domain Hydrolase and FAAH2) 6036 Containing 12) 6027 2.5.2. AFMID (Arylformamidase) 6037 2.2. Extracellular Neutral Lipases 6027 2.6. Acyl-CoA Hydrolases 6037 2.2.1. PNLIP (Pancreatic Lipase) 6028 2.6.1. FASN (Fatty Acid Synthase) 6037 2.2.2. PNLIPRP1 and PNLIPR2 (Pancreatic 2.6.2. -

2014 ADA Posters 1319-2206.Indd

INTEGRATED PHYSIOLOGY—INSULINCATEGORY SECRETION IN VIVO 1738-P increase in tumor size and pulmonary metastasis is observed, compared Sustained Action of Ceramide on Insulin Signaling in Muscle Cells: to wild type mice. In this study, we aimed to determine the mechanisms Implication of the Double-Stranded RNA Activated Protein Kinase through which hyperinsulinemia and the canonical IR signaling pathway drive RIMA HAGE HASSAN, ISABELLE HAINAULT, AGNIESZKA BLACHNIO-ZABIELSKA, tumor growth and metastasis. 100,000 MVT-1 (c-myc/vegf overexpressing) RANA MAHFOUZ, OLIVIER BOURRON, PASCAL FERRÉ, FABIENNE FOUFELLE, ERIC cells were injected orthotopically into 8-10 week old MKR mice. MKR mice HAJDUCH, Paris, France, Białystok, Poland developed signifi cantly larger MVT-1 (353.29±44mm3) tumor volumes than Intramyocellular accumulation of fatty acid derivatives like ceramide plays control mice (183.21±47mm3), p<0.05 with more numerous pulmonary a crucial role in altering the insulin message. If short-term action of ceramide metastases. Western blot and immunofl uorescent staining of primary tumors inhibits the protein kinase B (PKB/Akt), long-term action of ceramide on insulin showed an increase in vimentin, an intermediate fi lament, typically expressed signaling is less documented. Short-term treatment of either the C2C12 cell in cells of mesenchymal origin, and c-myc, a known transcription factor. Both line or human myotubes with palmitate (ceramide precursor, 16h) or directly vimentin and c-myc are associated with cancer metastasis. To assess if insulin with ceramide (2h) induces a loss of the insulin signal through the inhibition and IR signaling directly affects the expression these markers, in vitro studies of PKB/Akt. -

A Study of Blood Fatty Acids Profile in Hyperlipidemic and Normolipidemic

H OH metabolites OH Article A Study of Blood Fatty Acids Profile in Hyperlipidemic and Normolipidemic Subjects in Association with Common PNPLA3 and ABCB1 Polymorphisms Thomai Mouskeftara 1,2, Antonis Goulas 3, Despoina Ioannidou 3, Charikleia Ntenti 3, Dimitris Agapakis 4, Andreana Assimopoulou 5,6 and Helen Gika 1,2,* 1 Laboratory of Forensic Medicine and Toxicology, School of Medicine, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, 54124 Thessaloniki, Greece; [email protected] 2 Biomic AUTh, Center for Interdisciplinary Research and Innovation (CIRI-AUTH), 57001 Thessaloniki, Greece 3 Laboratory of Pharmacology, School of Medicine, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, 54124 Thessaloniki, Greece; [email protected] (A.G.); [email protected] (D.I.); [email protected] (C.N.) 4 Department of Internal Medicine, AHEPA Hospital, School of Medicine, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, 54124 Thessaloniki, Greece; [email protected] 5 Natural Products Research Center of Excellence (NatPro-AUTH), Center for Interdisciplinary Research and Innovation (CIRI-AUTH), 57001 Thessaloniki, Greece; [email protected] 6 Laboratory of Organic Chemistry, School of Chemical Engineering, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, 54124 Thessaloniki, Greece * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Adiponutrin (patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing 3; PNPLA3), encoded in humans by the PNPLA3 gene, is a protein associated with lipid droplet and endoplasmic reticulum Citation: Mouskeftara, T.; Goulas, A.; membranes, where it is apparently involved in fatty acid redistribution between triglycerides and Ioannidou, D.; Ntenti, C.; Agapakis, phospholipids. A common polymorphism of PNPLA3 (I148M, rs738409), linked to increased PNPLA3 D.; Assimopoulou, A.; Gika, H. A presence on lipid droplets, is a strong genetic determinant of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) Study of Blood Fatty Acids Profile in and of its progression. -

The PNPLA3‐I148M Variant Increases Polyunsaturated Triglycerides in Human Adipose Tissue

Received: 2 April 2020 | Revised: 23 April 2020 | Accepted: 2 May 2020 DOI: 10.1111/liv.14507 ORIGINAL ARTICLE The PNPLA3-I148M variant increases polyunsaturated triglycerides in human adipose tissue Sami Qadri1,2 | Susanna Lallukka-Brück1,2 | Panu K. Luukkonen1,2 | You Zhou2,3 | Amalia Gastaldelli4 | Marju Orho-Melander5 | Henna Sammalkorpi6 | Anne Juuti6 | Anne K. Penttilä6 | Julia Perttilä2 | Antti Hakkarainen7 | Tiina E. Lehtimäki7 | Matej Orešič8 | Tuulia Hyötyläinen8 | Leanne Hodson9,10 | Vesa M. Olkkonen2 | Hannele Yki-Järvinen1,2 1Department of Medicine, University of Helsinki and Helsinki University Hospital, Helsinki, Finland 2Minerva Foundation Institute for Medical Research, Helsinki, Finland 3Systems Immunity University Research Institute and Division of Infection and Immunity, School of Medicine, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK 4Institute of Clinical Physiology, National Research Council, Pisa, Italy 5Department of Clinical Sciences Malmö, Lund University, Malmö, Sweden 6Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, Abdominal Center, Helsinki University Hospital, Helsinki, Finland 7HUS Medical Imaging Center, Helsinki University Hospital, Helsinki, Finland 8Department of Chemistry, Örebro University, Örebro, Sweden 9Oxford Centre for Diabetes, Endocrinology and Metabolism, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK 10National Institute for Health Research Oxford Biomedical Research Centre, Oxford University Hospitals Foundation Trust, Oxford, UK Correspondence Sami Qadri, Biomedicum Helsinki 1, Room Abstract A417a, Haartmaninkatu 8, 00290 Helsinki, Background & Aims: The I148M variant in PNPLA3 is the major genetic risk factor for Finland. Email: [email protected] non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). The liver is enriched with polyunsaturated triglycerides (PUFA-TGs) in PNPLA3-I148M carriers. Gene expression data indicate Funding information Novo Nordisk Foundation; EU H2020-JTI- that PNPLA3 is liver-specific in humans, but whether it functions in adipose tissue IMI2 project 777377-2 Liver Investigation: (AT) is unknown. -

Crosstalk Between Hedgehog Pathway and Energy Pathways In

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Crosstalk between Hedgehog pathway and energy pathways in human adipose-derived stem Received: 6 February 2018 Accepted: 14 May 2018 cells: A deep sequencing analysis of Published: xx xx xxxx polysome-associated RNA Patrícia Shigunov1, Lucas Titton Balvedi1, Marlon Dias Mariano Santos2, Roberto H. Herai3, Alessandra Melo de Aguiar1 & Bruno Dallagiovanna1 Adult stem cells are considered promising candidates for cellular therapies due to their capacity to diferentiate and self-renew. Diferentiation leads to changes in the metabolism, structure, and gene expression patterns of cells. Hedgehog is one of the pathways that is involved in the enhancement of osteogenesis and chondrogenesis in adult stem cells, but its mechanisms are poorly understood. In this study, we treated adipose tissue-derived stem cells (ADSC) with two well-characterized drugs, purmorphamine (Hedgehog pathway activator) and cyclopamine (Hedgehog pathway inhibitor), and identifed mRNAs associated with polysomes in each treatment group to determine the post transcriptional genetic networks governed by the Hedgehog pathway. Activation of the Hedgehog pathway by purmorphamine results in signifcant upregulation of mRNAs associated with cellular communication and signal transduction. Furthermore, our experiments show that cyclopamine acts late downregulating GLI1 expression in ADSCs but promotes the upregulation of mRNAs associated with energy pathways and metabolism at early times. Through in silico analysis, we identifed some miRNAs, such as miR-355, that could regulate these mRNAs association with polysomes and thereby modulate the Hedgehog pathway. Our results suggest that activation of the Hedgehog pathway by purmorphamine also results in a negative regulation of mRNAs in the protein translation machinery. -

Meeting Abstracts from the 9Th International Conference on Cgmp: Generators, Efectors and Therapeutic Implications

J Transl Med 2019, 17(Suppl 2):254 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-019-1994-0 Journal of Translational Medicine MEETING ABSTRACTS Open Access Meeting abstracts from the 9th International Conference on cGMP: Generators, Efectors and Therapeutic Implications Germany. 14–16 June 2019 Published: 15 August 2019 S 1‑01 References NO‑sGC signaling and therapeutics in sickle cell and hemolytic 1. Ataga KI, Moore CG, Jones S, Olajide O, Strayhorn D, Hinderliter A, diseases Orringer EP. Pulmonary hypertension in patients with sickle cell disease: a Mark Gladwin1,2 longitudinal study. Br J Haematol. 2006;134:109–15. 1University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh Heart, Lung, Blood and Vascular 2. De Castro LM, Jonassaint JC, Graham FL, Ashley‑Koch A and Telen MJ. Medicine Institut, Pittsburgh Pennsylvania, US; 2University of Pittsburgh, Pulmonary hypertension associated with sickle cell disease: clini‑ Division of Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care Medicine, Department cal and laboratory endpoints and disease outcomes. Am J Hematol. of Medicine, Pittsburgh Pennsylvania, US 2008;83:19–25. Correspondence: Mark Gladwin ‑ [email protected] 3. Gladwin MT, Sachdev V, Jison ML, Shizukuda Y, Plehn JF, Minter K, Brown Journal of Translational Medicine 2019, 17(2):S 1‑01 B, Coles WA, Nichols JS, Ernst I, Hunter LA, Blackwelder WC, Schechter AN, Rodgers GP, Castro O and Ognibene FP. Pulmonary hypertension as Introduction: Nitric oxide (NO) is a critical regulator of vascular home- a risk factor for death in patients with sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. ostasis, increasing basal and fow-mediated vasodilation. Red blood 2004;350:886–95. cells can regulate NO bioavailability through an intrinsic nitrite (NO 2 ) 4. -

Relevance of the Epigenetic Regulation Exercised by Hepatic Micrornas in the Fatty Liver Arena: from the Bedside to the Bench

RELEVANCE OF THE EPIGENETIC REGULATION EXERCISED BY HEPATIC MICRORNAS IN THE FATTY LIVER ARENA: FROM THE BEDSIDE TO THE BENCH Jèssica Latorre Luque Per citar o enllaçar aquest document: Para citar o enlazar este documento: Use this url to cite or link to this publication: http://hdl.handle.net/10803/671499 ADVERTIMENT. L'accés als continguts d'aquesta tesi doctoral i la seva utilització ha de respectar els drets de la persona autora. Pot ser utilitzada per a consulta o estudi personal, així com en activitats o materials d'investigació i docència en els termes establerts a l'art. 32 del Text Refós de la Llei de Propietat Intel·lectual (RDL 1/1996). Per altres utilitzacions es requereix l'autorització prèvia i expressa de la persona autora. En qualsevol cas, en la utilització dels seus continguts caldrà indicar de forma clara el nom i cognoms de la persona autora i el títol de la tesi doctoral. No s'autoritza la seva reproducció o altres formes d'explotació efectuades amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva comunicació pública des d'un lloc aliè al servei TDX. Tampoc s'autoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant als continguts de la tesi com als seus resums i índexs. ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis doctoral y su utilización debe respetar los derechos de la persona autora. Puede ser utilizada para consulta o estudio personal, así como en actividades o materiales de investigación y docencia en los términos establecidos en el art. -

PNPLA3 Gene Patatin Like Phospholipase Domain Containing 3

PNPLA3 gene patatin like phospholipase domain containing 3 Normal Function The PNPLA3 gene provides instructions for making a protein called adiponutrin, which is found in fat cells (adipocytes) and liver cells (hepatocytes). The liver is a part of the digestive system that helps break down food, store energy, and remove waste products, including toxins. The function of the adiponutrin protein is not well understood, but it is thought to help regulate the development of adipocytes and the production and breakdown of fats (lipogenesis and lipolysis) in hepatocytes and adipocytes. Studies indicate that the activity (expression) of the PNPLA3 gene decreases during periods without food (fasting) and increases after eating, suggesting that the amount of adiponutrin protein produced is regulated as needed to help process and store fats in the diet. Health Conditions Related to Genetic Changes Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease A particular variation in the PNPLA3 gene has been associated with an increased risk of developing non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). NAFLD is a buildup of excessive fat in the liver that can lead to liver damage resembling the damage caused by alcohol abuse, but that occurs in people who do not drink heavily. In some cases NAFLD leads to inflammation of the liver (non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, also known as NASH) and permanent liver damage (cirrhosis). The PNPLA3 gene variation associated with NAFLD changes the protein building block ( amino acid) isoleucine to the amino acid methionine at protein position 148, written as Ile148Met or I148M. Research suggests that the altered protein leads to increased production and decreased breakdown of fats in the liver. -

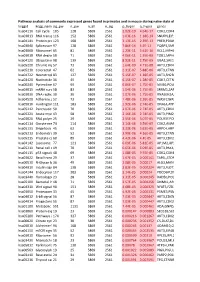

Pathway Analysis of Commonly Expressed Genes Found in Primates and in Mouse During Naïve State of Pluripotenc Keggid Kegg Names

Pathway analysis of commonly expressed genes found in primates and in mouse during naïve state of pluripotency. keggid kegg_namesig_pw n_pw n_all n_sig p_hyper q_hyper genes hsa04110 Cell cycle 105 128 5869 2561 2.02E-19 4.64E-17 CDK2,CDK4,CDK6,CDK7,CDKN1A,CDKN1B,STAG1,CDKN2B,ANAPC10,MAD2L2,STAG2,GADD45G,DBF4,YWHAQ,CHEK1,CHEK2,CREBBP,GADD45A,E2F1,E2F3,E2F4,E2F5,EP300,ORC3,CDC26,ABL1,ANAPC13,SFN,GSK3B,ANAPC2,ANAPC4,HDAC1,HDAC2,MAD2L1,SMAD2,SMAD3,SMAD4,MCM2,MCM3,MCM4,MCM5,MCM6,MCM7,MDM2,MYC,GADD45B,ATM,ORC1,ORC2,ORC4,ORC5,FZR1,ANAPC7,ANAPC11,PLK1,ATR,PRKDC,RAD21,RB1,RBL1,CCND1,ANAPC1,SKP2,BUB1,BUB1B,TFDP1,TFDP2,TGFB1,TGFB2,TTK,WEE1,YWHAB,YWHAE,YWHAG,YWHAH,YWHAZ,ZBTB17,SMC1A,CDC7,CDC45,MAD1L1,CDC14A,CDC23,CDC16,CCNA2,CCNB1,CCND2,CCND3,CCNE1,CCNH,PKMYT1,SMC3,CCNB2,CCNE2,BUB3,PTTG1,ESPL1,CDK1,CDC6,CDC20,CDC25A,CDC25B,CDC25C,CDC27,RBX1 hsa03013 RNA transport116 152 5869 2561 1.03E-16 1.18E-14 SNUPN,EIF1,POP7,SRRM1,SAP18,EIF1B,PRMT5,TACC3,NXF1,RPP30,RPP38,PAIP1,POP4,RPP40,RNPS1,POP1,STRAP,DDX20,XPOT,CLNS1A,NUP35,RPP25L,EEF1A1,EEF1A2,EIF2S1,EIF2B1,EIF4A1,EIF4B,EIF4E,EIF4EBP1,EIF4G1,EIF4G2,EIF5,CASC3,NCBP2,ACIN1,NUP205,NUP210,NUP62,GEMIN5,UPF2,PABPC1,NXT1,NUP43,EIF3E,KPNB1,MAGOH,NCBP1,NUP88,NUP98,GEMIN4,NMD3,POP5,PHAX,NUP54,PNN,RPP25,GEMIN8,MAGOHB,ELAC1,NDC1,NUP133,NXT2,NUP107,THOC2,XPO5,RAN,RANBP2,RANGAP1,SENP2,UPF1,ELAC2,SEC13,UPF3B,SMN1,SUMO3,SUMO2,TPR,SUMO1,XPO1,NUP37,DDX39B,THOC6,GEMIN7,GEMIN6,RPP21,NUP85,THOC7,NUP214,AAAS,SEH1L,THOC3,RAE1,THOC5,EIF3A,EIF3B,EIF3C,EIF3D,EIF3F,EIF3G,EIF3H,EIF3I,EIF4G3,PABPC4,EIF2B4,EIF2B2,EIF2B5,EIF2S2,EIF4E2,NUP155,EIF5B,TGS1,NUP93,EIF4A3,NUP153,THOC1 -

Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Table 2

Supplementary Table 1: The list of genes associated with platelet count retrieved from the Open Target Genetics platform (https://genetics.opentargets.org) Gene symbol Gene name GCSAML germinal center associated signaling and motility like SH2B3 SH2B adaptor protein 3 ARHGEF3 Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor 3 HBS1L HBS1 like translational GTPase THPO thrombopoietin JAK2 Janus kinase 2 BAK1 BCL2 antagonist/killer 1 RCL1 RNA terminal phosphate cyclase like 1 TUBB1 tubulin beta 1 class VI DNM3 dynamin 3 GCKR glucokinase regulator ABCC4 ATP binding cassette subfamily C member 4 JMJD1C jumonji domain containing 1C HIC1 HIC ZBTB transcriptional repressor 1 CARMIL1 capping protein regulator and myosin 1 linker 1 LY75 lymphocyte antigen 75 CBL Cbl proto-oncogene SLFN14 schlafen family member 14 RASSF3 Ras association domain family member 3 ZFPM2 zinc finger protein, FOG family member 2 CABLES1 Cdk5 and Abl enzyme substrate 1 LY75-CD302 LY75-CD302 readthrough ACTN1 actinin alpha 1 MARK4 microtubule affinity regulating kinase 4 AK3 adenylate kinase 3 RCOR1 REST corepressor 1 CD36 CD36 molecule FABP6 fatty acid binding protein 6 GP1BA glycoprotein Ib platelet subunit alpha novel pleckstrin homology domain containing, family O member 2 (PLEKHO2) and ankyrin repeat and death domain containing 1A AC069368.1 (ANKDD1A) protein ATXN2 ataxin 2 TRABD TraB domain containing TPM4 tropomyosin 4 GFI1B growth factor independent 1B transcriptional repressor TERT telomerase reverse transcriptase EGF epidermal growth factor NREP neuronal regeneration related -

Supplemental Figures 04 12 2017

Jung et al. 1 SUPPLEMENTAL FIGURES 2 3 Supplemental Figure 1. Clinical relevance of natural product methyltransferases (NPMTs) in brain disorders. (A) 4 Table summarizing characteristics of 11 NPMTs using data derived from the TCGA GBM and Rembrandt datasets for 5 relative expression levels and survival. In addition, published studies of the 11 NPMTs are summarized. (B) The 1 Jung et al. 6 expression levels of 10 NPMTs in glioblastoma versus non‐tumor brain are displayed in a heatmap, ranked by 7 significance and expression levels. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001. 8 2 Jung et al. 9 10 Supplemental Figure 2. Anatomical distribution of methyltransferase and metabolic signatures within 11 glioblastomas. The Ivy GAP dataset was downloaded and interrogated by histological structure for NNMT, NAMPT, 12 DNMT mRNA expression and selected gene expression signatures. The results are displayed on a heatmap. The 13 sample size of each histological region as indicated on the figure. 14 3 Jung et al. 15 16 Supplemental Figure 3. Altered expression of nicotinamide and nicotinate metabolism‐related enzymes in 17 glioblastoma. (A) Heatmap (fold change of expression) of whole 25 enzymes in the KEGG nicotinate and 18 nicotinamide metabolism gene set were analyzed in indicated glioblastoma expression datasets with Oncomine. 4 Jung et al. 19 Color bar intensity indicates percentile of fold change in glioblastoma relative to normal brain. (B) Nicotinamide and 20 nicotinate and methionine salvage pathways are displayed with the relative expression levels in glioblastoma 21 specimens in the TCGA GBM dataset indicated. 22 5 Jung et al. 23 24 Supplementary Figure 4. -

Transcriptional Regulation of the Human Alcohol

TRANSCRIPTIONAL REGULATION OF THE HUMAN ALCOHOL DEHYDROGENASES AND ALCOHOLISM Sirisha Pochareddy Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Indiana University September 2010 Accepted by the Faculty of Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Howard J. Edenberg, Ph.D., Chair Maureen A. Harrington, Ph.D. Doctoral Committee David G. Skalnik, Ph.D. Ann Roman, Ph.D. July 30, 2010 ii This work is dedicated to my parents and my brother for their unwavering support and unconditional love. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to sincerely thank my mentor Dr. Howard Edenberg, for his guidance, support throughout the five years of my research in his lab. It has been an amazing learning experience working with him and I am confident this training will help all through my research career. I would like to thank members of my research committee, Dr. Maureen Harrington, Dr. David Skalnik and Dr. Ann Roman. I am grateful to them for their guidance, encouraging comments, time and effort. I greatly appreciate Dr. Harrington’s questions during the committee meeting that helped me think broadly about my area of research. I am very thankful to Dr. Skalnik for reading through my manuscript and giving his valuable comments. My special thanks to Dr. Ann Roman for staying on my committee even after her retirement. I am also thankful to Dr. Jeanette McClintick for her patience in answering my never ending list of questions about the microarray analysis.