1 Diasporas and the Integration Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Monthly E-Newsletter for the Latest in Cultural Management and Policy ISSUE N° 114

news A monthly e-newsletter for the latest in cultural management and policy ISSUE N° 114 DIGEST VERSION FOR OUR FOLLOWERS Issue N°104 / news from encatc / Page 1 CONTENTS NOTE FROM THE Issue N°114 NOTE FROM THE EDITOR EDITOR 2 Dear colleagues, Welcome to the new re-vamped online ENCATC resources to make it ENCATC NEWS 3 version of our monthly ENCATC easier to access direct sources and newsletter! material for your work! Finally, for those who liked the PDF just as it was, These last two months we took the UPCOMING you can still find all the information time to have a critical look at this very 10 you trust from ENCATC and can print EVENTS product we have been producing for this publication to take with you! you for over 20 years as well as to CALLS & ask the opinions of members, key The new format of the ENCATC stakeholders, and loyal readers in newsletter will also offer more space OPPORTUNITIES 13 order to find the new way to adapt this for contributions from our members information tool to reading practices and stakeholders. In this issue you will EUROPEAN YEAR and the digital environment. enjoy articles written by our members Lidia Varbanova, Claire Giraud-Labalte OF CULTURAL 14 So what is the next stage for ENCATC and Savina Tarsitano and from the HERITAGE 2018 News? Many said they were plagued network Future for Religious Heritage. by information overload and felt pressure to have updates quickly and Finally, to mark the European Year of ENCATC IN only a click away. -

Updated: May 2021 1

Updated: May 2021 PATTI M. VALKENBURG University of Amsterdam Spui 21, 1012 WX Amsterdam Tel: +31205256074 [email protected] www.pattivalkenburg.nl www.ccam-ascor.nl www.project-awesome.nl @pmvalkenburg BIOGRAPHY Patti M. Valkenburg is a University Distinguished Professor at the University of Amsterdam. Her research focuses on the cognitive, emotional, and social effects of (social) media on youth and adults. Her interdisciplinary research has been recognized by multiple grants and awards, including a Vici grant from the Dutch Research Council (NWO, 2003), an Advanced Grant from the European Research Council (ERC, 2010), the Spinoza Award from NWO (2011), the Hendrik Muller Award from the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW, 2011), and the Career Achievement Award by the International Communication Association (ICA, 2016). Valkenburg is a fellow of the ICA, of the Association for Psychological Science (APS), the KNAW, and the Royal Holland Society of Science and Humanities (KHMW). In 2003, she founded CcaM, the Center for Research on Children, Adolescents, and the Media. CcaM is part of the Amsterdam School of Communication Research ASCoR, which has been ranked #1 worldwide in both the Shanghai Global Ranking and the QS World Ranking. Valkenburg is a strong proponent of open science, and is the author of 160+ academic articles, 40+ book chapters, and 8 books. Her work has been cited over 30,000 times. Her most recent open access book, Plugged In, was published by Yale University Press. TOP 3 PUBLICATIONS Valkenburg, P.M. & Peter, J. (2013). The differential susceptibility to media effects model. Journal of Communication, 63, 221-243. -

The Many Faces of Strategic Voting

Revised Pages The Many Faces of Strategic Voting Strategic voting is classically defined as voting for one’s second pre- ferred option to prevent one’s least preferred option from winning when one’s first preference has no chance. Voters want their votes to be effective, and casting a ballot that will have no influence on an election is undesirable. Thus, some voters cast strategic ballots when they decide that doing so is useful. This edited volume includes case studies of strategic voting behavior in Israel, Germany, Japan, Belgium, Spain, Switzerland, Canada, and the United Kingdom, providing a conceptual framework for understanding strategic voting behavior in all types of electoral systems. The classic definition explicitly considers strategic voting in a single race with at least three candidates and a single winner. This situation is more com- mon in electoral systems that have single- member districts that employ plurality or majoritarian electoral rules and have multiparty systems. Indeed, much of the literature on strategic voting to date has considered elections in Canada and the United Kingdom. This book contributes to a more general understanding of strategic voting behavior by tak- ing into account a wide variety of institutional contexts, such as single transferable vote rules, proportional representation, two- round elec- tions, and mixed electoral systems. Laura B. Stephenson is Professor of Political Science at the University of Western Ontario. John Aldrich is Pfizer- Pratt University Professor of Political Science at Duke University. André Blais is Professor of Political Science at the Université de Montréal. Revised Pages Revised Pages THE MANY FACES OF STRATEGIC VOTING Tactical Behavior in Electoral Systems Around the World Edited by Laura B. -

Prague Conference Theme Highlights

VOLUME 46, ISSUE 2 MARCH 2018 Prague Conference Theme Highlights by Patricia Moy Sheila Coronel (Columbia U) focuses on ICA President-Elect, U Of Washington technology and voice, juxtaposing the pow- er of the early web to break the monopoly of information against the current use of social Theme Sessions media for disinformation and harassment purposes. Philip Howard (Oxford U) closes by Under the stewardship of conference theme presenting five design principles that allow for chair Donald Matheson (U of Canterbury), building civic engagement and voice into the the Prague program includes sessions that internet of things. speak to voice in markedly different and in- novative ways: Monday Noon Plenary: His Master’s Voice • Agonistic Voices and Deliberative Politics: Nearly three-quarters of a century ago, Paul Contestation and Dialogue Across the Lazarsfeld’s two-step flow of communica- Globe tion proposed that voting decisions often are • A Voice of Our Own: Labor, Power, and made by consulting other individuals, and Representation in the New Cultural Indus- that many of these others are typically more tries exposed to the media than those who con- • Can You Hear Me Now? Marginalized sulted them. In the 1940s, the tools of em- Voices on Social Media pirical research allowed for the study of only With the release of the Prague program, at- • Conceptualizing the Friendly Voice: How two steps. Lazarsfeld’s model has served as tendees now can start planning their intellec- to Achieve Peace Through Amicable a prelude to the empirical study of networks, tual (and leisure) time at ICA. The lion’s share Communication? and to the role of networks in the diffusion of of the four-day conference comprises ses- • Enabling Citizen and Community Voices innovation. -

Jessica Taylor Piotrowski, Ph.D

Updated: May 19 Jessica Taylor Piotrowski, Ph.D. Department of Communication Science The Amsterdam School of Communication Research (ASCoR) University of Amsterdam PO Box 15791 |1001 NG Amsterdam |The Netherlands (O) +31 06 5541 7618 [email protected] www.jessicataylorpiotrowski.com ACADEMIC AND RESEARCH APPOINTMENTS Associate Professor, The Amsterdam School of Communication Research (ASCoR), Department of Communication Science, University of Amsterdam, August 2014 to present. *Basiskwalificatie Onderwijs, August 2014 *Program Group Leader, Youth & Media Entertainment, September 2015 to present. *Director, Entertainment Communication Master track, September 2015 to present. *Communication Science representative, Knowledge Officer, FMG Educational Innovation Workgroup (werkgroep kennisdeling, chairperson), March 2017 to present. *FMG representative, Matchmaker, FMG Kennisdeling Onderwijs, September 2017 to present. Director, Center for research on Children, Adolescents, and the Media (CcaM), The Amsterdam School of Communication Research (ASCoR), University of Amsterdam, November 2013 to present. Co-Investigator, “The entertainization of childhood: an etiology of risks and opportunities”, The Amsterdam School of Communication Research (ASCoR), University of Amsterdam, January 2012 to August 2016. Assistant Professor (tenured July 2013), The Amsterdam School of Communication Research (ASCoR), Department of Communication Science, University of Amsterdam, January 2012 to July 2014. Visiting Assistant Professor, Department of Communication -

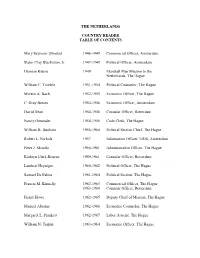

The Netherlands Country Reader Table of Contents

THE NETHERLANDS COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS Mary Seymour Olmsted 1946-1949 Commercial Officer, Amsterdam Slator Clay Blackiston, Jr. 194 -1949 Political Officer, Amsterdam Herman Kleine 1949 Marshall Plan Mission to the Netherlands, The Hague (illiam C. Trimble 1951-1954 Political Counselor, The Hague Morton A. Bach 1952-1955 ,conomic Officer, The Hague C. -ray Bream 1954-1956 ,conomic Officer, Amsterdam .avid .ean 1954-1956 Consular Officer, 0otterdam Nancy Ostrander 1954-1956 Code Clerk, The Hague (illiam B. .unham 1956-1961 Political Section Chief, The Hague 0obert 2. Nichols 195 Information Officer, 4SIS, Amsterdam Peter J. Skoufis 1958-1961 Administrative Officer, The Hague Kathryn Clark-Bourne 1959-1961 Consular Officer, 0otterdam 2ambert Heyniger 1961-1962 Political Officer, The Hague Samuel .e Palma 1961-1964 Political Section, The Hague 6rancis M. Kinnelly 1962-1963 Commercial Officer, The Hague 1963-1964 Consular Officer, 0otterdam 6isher Ho8e 1962-1965 .eputy Chief of Mission, The Hague Manuel Abrams 1962-1966 ,conomic Counselor, The Hague Margaret 2. Plunkett 1962-196 2abor Attach:, The Hague (illiam N. Turpin 1963-1964 ,conomic Officer, The Hague .onald 0. Norland 1964-1969 Political Officer, The Hague ,mmerson M. Bro8n 1966-19 1 ,conomic Counselor, The Hague Thomas J. .unnigan 1969-19 2 Political Counselor, The Hague J. (illiam Middendorf, II 1969-19 3 Ambassador, Netherlands ,lden B. ,rickson 19 1-19 4 Consul -eneral, 0otterdam ,ugene M. Braderman 19 1-19 4 Political Officer, Amsterdam 0ay ,. Jones 19 1-19 2 Secretary, The Hague (ayne 2eininger 19 4-19 6 Consular / Administrative Officer, 0otterdam Martin Van Heuven 1932-194 Childhood, 4trecht 19 5-19 8 Political Counselor, The Hague ,lizabeth Ann Bro8n 19 5-19 9 .eputy Chief of Mission, The Hague Victor 2. -

A Monthly E-Newsletter for the Latest in Cultural Management and Policy ISSUE N° 118

news A monthly e-newsletter for the latest in cultural management and policy ISSUE N° 118 DIGEST VERSION FOR OUR FOLLOWERS Issue N°104 / news from encatc / Page 1 CONTENTS Issue N°118 NOTE FROM THE NOTE FROM THE EDITOR EDITOR 2 Dear colleagues, On 6 July, Tibor Navracsics, European integrated master programmes and ENCATC NEWS 3 Commissioner for Education, Culture, provide scholarships for talented Youth and Sport, and Yoshimasa students from Europe and Japan to Hayashi, Japan Minister of Education, study abroad. The second is a short- UPCOMING Culture, Sports, Science and term staff-exchange programme for EVENTS 7 Technology (MEXT), met in Budapest EU and MEXT officials to promote to officially launch the EU-Japan peer-learning and boost cooperation. Policy dialogue on Education, Culture Both initiatives emphasise the CALLS & 10 and Sport. importance of people-to-people OPPORTUNITIES contacts within the EU-Japan The 2018 ENCATC International Study relations. Tour and the ENCATC Academy on EUROPEAN YEAR Cultural Policy and Cultural ENCATC wishes to bring its OF CULTURAL 11 Diplomacy next 5‑-9 November will be contribution to the recent EU HERITAGE 2018 in Tokyo, Japan are timely with these statement. Therefore, our 2018 recent European policy developments. International Study Tour and Academy will gather academics, In the field of education, both leaders researchers and professionals from ENCATC IN confirmed the importance of the cultural and academic sector CONTACT 14 promoting international cooperation across Europe and Japan. INTERVIEW in higher education. Erasmus+ was highlighted as a flagship programme, I encourage you to join our 5‑-day offering an excellent tool to promote intensive learning programme in Tokyo MEMBERS’ 16 international mobility and allow to boost project development and CORNER students to develop essential synergies between your university in transversal skills, while contributing to Europe and your counterpart in Japan, enhancing the relevance and quality of to learn about the current cultural ENCATC EU 22 education. -

Manifesto Collection of Signatures

Europe Europe Day Manifesto - List of Signatories Last Name First Name Institution / Organisation (if any) Function (if any) City Country 1 Abdelmonaem Asmaa MOTA Heritage Management specialist Cairo Egypt 2 AEP ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA DEPAISAJISTASASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA DE PAISAJISTAS Association of Landscape and Landscape Architecture ProfessionalsMADRID in Spain. Spain 3 Agenjo Xavier Fundación Ignacio Larramendi Director de Proyectos Madrid Spain 4 Agostini Caterina Rutgers University Ph.D. candidate, Europeana Network Association member Washington DC United States of America 5 Ahmedien Diaa Helwan University Lecturer Cairo Egypt 6 Aigner Thomas ICARUS - International Centre for Archival Research President Vienna Austria 7 Akkeren Shannen Eindhoven Netherlands 8 Alberotanzs Roberta Icomos Italia Member Luxembourg Luxembourg 9 Aleksova Ana Directorate for Protection of Cultural Heritage Junior Associate for International Assistance and Cooperation Skopje North Macedonia 10 Alexia Radu Baile Govora Romania 11 Alkemade Henk RCE Specialist Historic Landscapes Dieren Netherlands 12 Alleaume Anne-Lise Réseau Art Nouveau Network Coordinator 13 Alliaudi Elena Network of European Royal Residences Coordinator Versailles France 14 Alonso Beatriz Proacttia Cultural management CEO Valladolid Spain 15 Alonso Jose PROSKENE Conservation and Cultural Heritage Director Madrid Spain 16 Alonso Quintela Montserrat Vigo Spain 17 Alorda Martí Angels UB Estudiant Barcelona Spain 18 Altintaş Yusuf Kayseri Turkey 19 Alvarez Lula Independent Consultant Strasbourg -

An Analysis of the Costs of Dismantling and Cleaning up Synthetic Drug Production Sites in Belgium and the Netherlands

An analysis of the costs of dismantling and cleaning up synthetic drug production sites in Belgium and the Netherlands Background paper commissioned by the EMCDDA for the EU Drug Markets Report 2019 Author Maaike Claessens, Wim Hardyns, Freya Vander Laenen and Nick Verhaeghe, Institute for International Research on Criminal Policy, Ghent University, Belgium 2019 This paper was commissioned by the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) to provide background material to inform and contribute to the drafting of the EU Drug Markets Report (EDMR) 2019. This background paper was produced under contract no CT.18.SAS.0025.1.0 and we are grateful for the valuable contribution of the authors. The paper has been cited within the EDMR 2019 and is also being made available online for those who would like further information on the topic. However, the views, interpretations and conclusions set out in this publication are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of the EMCDDA or its partners, any EU Member State or any agency or institution of the European Union. 2 Table of contents Introduction ................................................................................................................. 4 Methodology ............................................................................................................... 6 Literature review................................................................................................................. 6 Stakeholder interviews ...................................................................................................... -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY SOURCES CITED OR CONSULTED UNPUBLISHED SOURCES Archives du Ministere des Affaires Etrangeres, Bruxelles. Haus-, Hof- und Staatsarchiv, \Vien. Ministere des Affaires Etrangeres, Paris. Ministero degli Affari Esteri. Archivio Esteri, Roma. Public Record Office, (Foreign Oflice General Correspondence), London. OFFICIAL PUBLISHED SOURCES Annuario Pontificio, Roma, 1860--1870; 1912- Atti Ufficiali del Parlamento Italiano, Firenze. British and Foreign State Papers, London. 1841- British Parliamentary Papers, House of Commons. (The "Blue Books") (La) Gerarchia della Chiesa e la Famiglia Pontificia per l'anno .... Roma. 1872-1911. (Die) Grosse Politik der Europaischen Kabinette I87I-I9I4. Sammlung der Diplomatischen Akten des Auswartigen Amtes, Berlin, 1926, 40 vols. Ministere des Af/aires Etrangeres, Documents Diplomatiques Franfais (I87I-I9I4), Iere serie (I87I--I900), 1929-1947, 11 tomes. -- La Politique Exterieure de l'Allemagne I87o-I9I4, Documents Olficiels publies par Ie Ministere Allemand des Alfaires Etrangeres. Paris, 1927-1939, 32 tomes. Translation of portions of Die Grosse Politik. Ministerium des K. und K. Hauses und des Aeussern. Auswartige Angelegenheiten. Correspondenzen und Aktenstucke, I868-I874, Wien, 1868-1874. (Eight "Red Books".) Ministero degZi Affari Esteri. Documenti DipZomatici relativi aZla Ques tione Romana communicati dal Ministero degli Alfari Esteri nella tornata delI9 dicembre I870. CameradeZdeputati. Sessione I87o-I87I. Prima della XI LegisZatura. Doc. No. 46. Napoleon Ier, Correspondance pubZiee par ordre de l'Empereur Napoleon III, Paris, Imprimerie ImpE,riale, 1858-1869, 32 vols. Patti Lateranensi. Convenzioni e Accordi successivi Ira IZ Vaticano e l'ItaZia, Tipografia Polyglotta Vaticana, 1946. Segreteria di Stato. Istruzione reZativa aZ diriito di Precedenza dei rap presentanti Pontilicii nel Corpo DipZomatico, Roma, Tipografia Vaticana, [April, 1900J. -

Newsletter VOLUME 46, ISSUE 5 JUNE/JULY 2018 President’S Message: Highlights from Prague by Patricia Moy, ICA President, U of Washington

INTERNATIONAL COMMUNICATION ASSOCIATION newsletter VOLUME 46, ISSUE 5 JUNE/JULY 2018 President’s Message: Highlights from Prague by Patricia Moy, ICA President, U of Washington With yet another intellectually vibrant annual conference behind us, I’m delighted to share some conference highlights with those might not have been able make it to Prague or attend a given session. The Prague conference has much about which to boast. In quantitative terms, this past year saw a record-breaking number of submissions (4,803 papers and 434 panels) as well as the highest number of attendees (3,545). Thanks to the 32 Division and Interest Group (D/ IG) program planners who creatively crafted high-density sessions and hybrid interactive sessions, we were able to accommodate more presentations than if we had only traditional four- or five-paper panels. That the vast (Columbia U), and Philip Howard majority of D/IGs included sessions (Oxford U) painted a nuanced portrait directly addressing the conference of how voice has been enabled and theme, Voices, speaks to the concept’s fostered, as well as suppressed and relevance to our discipline. From manipulated, over time and space. The Communication Law & Policy’s session Monday plenary, His Master’s Voice, on how weaponized intellectual property featured Elihu Katz (U of Pennsylvania) is used to raise and silence voices to illustrating how Paul Lazarsfeld has Visual Communication Studies’ session shaped the discipline and, in particular, on visualizing the voices of protest on the study of social networks. Following global screens, the Prague program up with a discussion of the influence included a robust number of sessions of Gabriel Tarde and how voice is that complemented those overseen being studied today, Katz’s talk was by conference theme chair Donald professionally recorded and will be Matheson (U of Canterbury). -

Law, Time, and Sovereignty in Central Europe: Imperial Constitutions, Historical Rights, and the Afterlives of Empire

Law, Time, and Sovereignty in Central Europe: Imperial Constitutions, Historical Rights, and the Afterlives of Empire Natasha Wheatley Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2016 © 2016 Natasha Wheatley All rights reserved ABSTRACT Law, Time, and Sovereignty in Central Europe: Imperial Constitutions, Historical Rights, and the Afterlives of Empire Natasha Wheatley This dissertation is a study of the codification of empire and its unexpected consequences. It returns to the constitutional history of the Austro-Hungarian Empire — a subject whose heyday had passed by the late 1920s — to offer a new history of sovereignty in Central Europe. It argues that the imperatives of imperial constitutionalism spurred the creation a rich jurisprudence on the death, birth, and survival of states; and that this jurisprudence, in turn, outlived the imperial context of its formation and shaped the “new international order” in interwar Central Europe. “Law, Time, and Sovereignty” documents how contemporaries “thought themselves through” the transition from a dynastic Europe of two-bodied emperor-kings to the world of the League of Nations. The project of writing an imperial constitution, triggered by the revolutions of 1848, forced jurists, politicians and others to articulate the genesis, logic, and evolution of imperial rule, generating in the process a bank or archive of imperial self-knowledge. Searching for the right language to describe imperial sovereignty entailed the creative translation of the structures and relationships of medieval composite monarchy into the conceptual molds of nineteenth-century legal thought. While the empire’s constituent principalities (especially Hungary and Bohemia) theoretically possessed autonomy, centuries of slow centralization from Vienna had rendered that legal independence immaterial.