Cross-Channel Marriage and Royal Succession in the Age of Charles the Simple and Athelstan (C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Carolingian Past in Post-Carolingian Europe Simon Maclean

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository 1 The Carolingian Past in Post-Carolingian Europe Simon MacLean On 28 January 893, a 13-year-old known to posterity as Charles III “the Simple” (or “Straightforward”) was crowned king of West Francia at the great cathedral of Rheims. Charles was a great-great-grandson in the direct male line of the emperor Charlemagne andclung tightly to his Carolingian heritage throughout his life.1 Indeed, 28 January was chosen for the coronation precisely because it was the anniversary of his great ancestor’s death in 814. However, the coronation, for all its pointed symbolism, was not a simple continuation of his family’s long-standing hegemony – it was an act of rebellion. Five years earlier, in 888, a dearth of viable successors to the emperor Charles the Fat had shattered the monopoly on royal authority which the Carolingian dynasty had claimed since 751. The succession crisis resolved itself via the appearance in all of the Frankish kingdoms of kings from outside the family’s male line (and in some cases from outside the family altogether) including, in West Francia, the erstwhile count of Paris Odo – and while Charles’s family would again hold royal status for a substantial part of the tenth century, in the long run it was Odo’s, the Capetians, which prevailed. Charles the Simple, then, was a man displaced in time: a Carolingian marooned in a post-Carolingian political world where belonging to the dynasty of Charlemagne had lost its hegemonic significance , however loudly it was proclaimed.2 His dilemma represents a peculiar syndrome of the tenth century and stands as a symbol for the theme of this article, which asks how members of the tenth-century ruling class perceived their relationship to the Carolingian past. -

LECTURE 5 the Origins of Feudalism

OUTLINE — LECTURE 5 The Origins of Feudalism A Brief Sketch of Political History from Clovis (d. 511) to Henry IV (d. 1106) 632 death of Mohammed The map above shows to the growth of the califate to roughly 750. The map above shows Europe and the East Roman Empire from 533 to roughly 600. – 2 – The map above shows the growth of Frankish power from 481 to 814. 486 – 511 Clovis, son of Merovich, king of the Franks 629 – 639 Dagobert, last effective Merovingian king of the Franks 680 – 714 Pepin of Heristal, mayor of the palace 714 – 741 Charles Martel, mayor (732(3), battle of Tours/Poitiers) 714 – 751 - 768 Pepin the Short, mayor then king 768 – 814 Charlemagne, king (emperor, 800 – 814) 814 – 840 Louis the Pious (emperor) – 3 – The map shows the Carolingian empire, the Byzantine empire, and the Califate in 814. – 4 – The map shows the breakup of the Carolingian empire from 843–888. West Middle East 840–77 Charles the Bald 840–55 Lothair, emp. 840–76 Louis the German 855–69 Lothair II – 5 – The map shows the routes of various Germanic invaders from 150 to 1066. Our focus here is on those in dark orange, whom Shepherd calls ‘Northmen: Danes and Normans’, popularly ‘Vikings’. – 6 – The map shows Europe and the Byzantine empire about the year 1000. France Germany 898–922 Charles the Simple 919–36 Henry the Fowler 936–62–73 Otto the Great, kg. emp. 973–83 Otto II 987–96 Hugh Capet 983–1002 Otto III 1002–1024 Henry II 996–1031 Robert II the Pious 1024–39 Conrad II 1031–1060 Henry I 1039–56 Henry III 1060–1108 Philip I 1056–1106 Henry IV – 7 – The map shows Europe and the Mediterranean lands in roughly the year 1097. -

Month End Financial Report

Austintown Local Schools Month End Financial Report November FY2020 Blaise Karlovic, Treasurer/CFO FUND SCC Description Beginning Balance MTD Receipts FYTD Receipts MTD Expenditures FYTD Expenditures Current Fund Balance Current Encumbrances Unencumbered Fund Balance 1 0 GENERAL FUND 10,590,599.45 3,397,719.71 21,298,926.65 4,095,775.24 20,330,275.97 11,559,250.13 1,877,802.40 9,681,447.73 1 9100 GF--BUS PURCHASE FUND 68,719.94 192.14 861.78 0.00 0.00 69,581.72 0.00 69,581.72 10,659,319.39 3,397,911.85 21,299,788.43 4,095,775.24 20,330,275.97 11,628,831.85 1,877,802.40 9,751,029.45 2 9004 Bond Retirement--AMS Middle School Project 1,949,693.95 114,821.39 850,028.12 1,476,337.50 1,784,465.92 1,015,256.15 0.00 1,015,256.15 2 9005 Bond Retirement--HB264 Project (2006) 0.00 32,673.74 32,673.74 2,970.34 14,851.70 17,822.04 17,822.04 0.00 2 9006 BOND RETIREMENT- OSFC PROJECT (k-2 3-5) 967,426.93 91,064.61 970,493.79 0.00 950,721.07 987,199.65 0.00 987,199.65 2,917,120.88 238,559.74 1,853,195.65 1,479,307.84 2,750,038.69 2,020,277.84 17,822.04 2,002,455.80 3 0 PERMANENT IMPROVEMENT FUND 2,277,611.68 0.00 0.00 16,905.00 16,905.00 2,260,706.68 0.00 2,260,706.68 4 9001 Building--Sale of Property 125,713.75 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 125,713.75 0.00 125,713.75 6 0 FOOD SERVICE 579,507.55 204,512.76 549,626.02 188,714.84 699,882.10 429,251.47 467,642.09 -38,390.62 7 0 UNCLAIMED FUNDS 0.00 13,254.26 13,254.26 0.00 0.00 13,254.26 0.00 13,254.26 7 9001 Sunshine Club AIS 465.05 0.00 3,025.00 200.00 200.00 3,290.05 2,300.00 990.05 7 9101 LYNDA MOLNAR SCHOLARSHIP -

Veronica Ortenberg “The King from Overseas”: Why Did Aethelstan Matter in Tenth-Century Continental Affairs?

Veronica Ortenberg “The King from Overseas”: Why Did Aethelstan Matter in Tenth-Century Continental Affairs? [A stampa in England and the Continent in the Tenth Century, a cura di D. Rollason e C. Leyser, Turnhout, Brepols, 2011, pp. 211-236 © dell’autrice - Distribuito in formato digitale da “Reti Medievali”, www.retimedievali.it]. Part II Kingship, Royal Models, and Dynastic Strategies ‘THE KING FROM OVERSEAS’: WHY DID ÆTHELSTAN MATTER IN TENTH-CENTURY CONTINENTAL AFFAIRS? Veronica Ortenberg ccording to the tenth-century chronicler Flodoard, Æthelstan, king of Wessex (924–39), was ‘the king from overseas’.1 In the early twelfth Acentury William of Malmesbury wrote of him: This explains why the whole of Europe sang his praises and extolled his merits to the sky; kings of other nations, not without reason, thought themselves fortunate if they could buy his friendship either by family alliances or by gifts.2 Was this a case of William of Malmesbury’s hyperbole? How far did it correspond with the reality of Æthelstan’s reign, the perception of him by his contemporaries, and his own perception of his role in Continental politics? Æthelstan’s Carolingian heritage had its origins in the mid-ninth century. The story of Æthelwulf’s marriage in 856 to Judith, Charles the Bald’s daughter, and its implications, notably in terms of Judith’s anointing and coronation in West Francia prior to her arrival in England, with an English coronation ordo adapted by Hincmar, are familiar.3 A great deal has been made, justifiably, of the impact of 1 ‘Alstanus rex […] a transmarinis regionibus’: Flodoard (Lauer), p. -

Possibilities of Royal Power in the Late Carolingian Age: Charles III the Simple

Possibilities of royal power in the late Carolingian age: Charles III the Simple Summary The thesis aims to determine the possibilities of royal power in the late Carolingian age, analysing the reign of Charles III the Simple (893/898-923). His predecessors’ reigns up to the death of his grandfather Charles II the Bald (843-877) serve as basis for comparison, thus also allowing to identify mid-term developments in the political structures shaping the Frankish world toward the turn from the 9th to the 10th century. Royal power is understood to have derived from the interaction of the ruler with the nobles around him. Following the reading of modern scholarship, the latter are considered as partners of the former, participating in the royal decision-making process and at the same time acting as executors of these decisions, thus transmitting the royal power into the various parts of the realm. Hence, the question for the royal room for manoeuvre is a question of the relations between the ruler and the nobles around him. Accordingly, the analysis of these relations forms the core part of the study. Based on the royal diplomas, interpreted in the context of the narrative evidence, the noble networks in contact with the rulers are revealed and their influence examined. Thus, over the course of the reigns of Louis II the Stammerer (877-879) and his sons Louis III (879-882) and Carloman II (879-884) up until the rule of Charles III the Fat (884-888), the existence of first one, then two groups of nobles significantly influencing royal politics become visible. -

Glossar the Disintegration of the Carolingian Empire

Tabelle1 Bavaria today Germany’s largest state, located in the Bayern Southeast besiege, v surround with armed forces belagern Bretons an ethnic group located in the Northwest of Bretonen France Carpathian Mountains a range of mountains forming an arc of roughly Karpaten 1,500 km across Central and Eastern Europe, Charles the Fat (Charles III) 839 – 888, King of Alemannia from 876, King Karl III. of Italy from 879, Roman Emperor (as Charles III) from 881 Danelaw an area in England in which the laws of the Danelag Danes were enforced instead of the laws of the Anglo-Saxons Franconia today mainly a part of Bavaria, the medieval Franken duchy Franconia included towns such as Mainz and Frankfurt Henry I 876 – 936, the duke of Saxony from 912 and Heinrich I. king of East Francia from 919 until his death Huns a confederation of nomadic tribes that invaded Hunnen Europe around 370 AD Lombardy a region in Northern Italy Lombardei Lorraine a historical area in present-day Northeast Lothringen France, a part of the kingdom Lotharingia Lothar I (Lothair I) 795 – 855, the eldest son of the Carolingian Lothar I. emperor Louis I and his first wife Ermengarde, king of Italy (818 – 855), Emperor of the Franks (840 – 855) Lotharingia a kingdom in Western Europe, it existed from Lothringen 843 – 870; not to be confused with Lorraine Louis I (Louis the Pious 778 – 840, also called the Fair, and the Ludwig I. Debonaire; only surviving son of Charlemagne; King of the Franks Louis the German (Louis II) ca. 806 – 876, third son of Louis I, King of Ludwig der Bavaria (817 – 876) and King of East Francia Deutsche (843 – 876) Louis the Younger (Louis III) 835 – 882, son of Louis the German, King of Ludwig III., der Saxony (876-882) and King of Bavaria (880- Jüngere 882), succeeded by his younger brother, Charles the Fat, Magyars an ethnic group primarily associated with Ungarn Hungary. -

INTRODUCTION the Value of Milgard Aluminum

INTRODUCTION The Value of Milgard Aluminum The Value of Milgard Aluminum Milgard Windows is a full-line manufacturer of windows and doors offering Vinyl, Aluminum, and Fiberglass products that are made to order every time. We can create just about any shape or style you can imagine within our wide range of operating styles. IT TAKES AN OPEN MIND. –– Our engineering teams design our Aluminum windows and patio doors individually with perfor- mance, appearance and energy conservation in mind. –– At Milgard, we’ll continue to innovate and adapt to everchanging architectural styles and construction practices to provide you with the most advanced Aluminum windows and doors on the market. DESIGN UNLIMITED. –– Mix and match Milgard Aluminum windows and patio doors from a wide array of shapes and sizes. Select matching window grids con- veniently located between the panes of glass. Corrosion resistant hardware is available for those areas where corrosion is a problem. A QUALITY COMMITMENT. –– It all starts with Milgard’s Full Lifetime War- ranty. Our promise that we will repair or replace any Milgard product defective in materials or workmanship for as long as your customer owns and resides in their single family home. For com- mercial projects, Milgard offers a Full ten year War- ranty. Our Aluminum windows are and patio doors designed to remain durable and operate smoothly for a lifetime. Our Quality Teams precision-build each window, one at a time, by hand. Just like we’ve built our windows for over 45 years. For complete warranty details visit milgard.com. INTRO APRIL 2009 ALUMINUM Guide Spec: Standard Aluminum Windows & Doors 3 Part Specification STANDARD Standard Aluminum Windows ALUMINUM WINDOWS - 08 51 13 With the thin lines that Migard’s Aluminum Windows provide, they are ideal for both new construction as well as replacement. -

Introduction

Cambridge University Press 0521819458 - Kingship and Politics in the Late Ninth Century: Charles the Fat and the End of the Carolingian Empire Simon Maclean Excerpt More information Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION the end of the carolingian empire in modern historiography The dregs of the Carlovingian race no longer exhibited any symptoms of virtue or power, and the ridiculous epithets of the Bald, the Stammerer, the Fat, and the Simple, distinguished the tame and uniform features of a crowd of kings alike deserving of oblivion. By the failure of the collateral branches, the whole inheritance devolved to Charles the Fat, the last emperor of his family: his insanity authorised the desertion of Germany, Italy, and France...Thegovernors,the bishops and the lords usurped the fragments of the falling empire.1 This was how, in the late eighteenth century, the great Enlightenment historianEdward Gibbonpassed verdict onthe endof the Carolingian empire almost exactly 900 years earlier. To twenty-first-century eyes, the terms of this assessment may seem jarring. Gibbon’s emphasis on the im- portance of virtue and his ideas about who or what was a deserving subject of historical study very much reflect the values of his age, the expectations of his audience and the intentions of his work.2 However, if the timbre of his analysis now feels dated, its constituent elements have nonetheless survived into modern historiography. The conventional narrative of the end of the empire in the year 888 is still a story about the emergence of recognisable medieval kingdoms which would become modern nations – France, Germany and Italy; about the personal inadequacies of late ninth- century kings as rulers; and about their powerlessness in the face of an increasingly independent, acquisitive and assertive aristocracy. -

Memory and Identity in Flodoard of Reims: His Use of the Roman Past

E MMA B E DDO E Memory and identity in Flodoard of Reims: his use of the Roman past The Historia Remensis ecclesiae of Flodoard of Reims is a history of that church and diocese from its mythical foundations until Flodoard’s own time, around the mid tenth century. His role as archivist of the church of Reims must have given him complete access to its records, and a unique understanding of the history of his city and church. The various sources were utilised by Flodoard for what they could tell him about this past, which he then reformed in his own fashion when he wrote the account of it. It is only by working backwards from his text that it is possible to unravel the smooth finished result and uncover the sometimes disparate sources and evidence which he used to create this polished narrative. This process of assessment and adjustment is more easily uncovered in his first few chapters in which he dealt with the distant foundation of Reims, and its Roman past, than in his later books. In these first chapters, not only did he state which sources he was using, but his classical sources are also mostly extant, so allowing for a detailed examination of his text and of the way he used his sources. In addition to the written sources available, the contemporary oral tra- ditions and the evidence from the physical remains in the landscape around him also influenced his portrayal of this distant past of Reims. Both the collective memories of his contemporaries in Reims and the historical memories of Reims which he read in the classical sources were adapted by Flodoard when writing what he felt was the appropriate history of his town and church. -

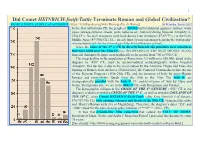

Did Comet HEINRICH-Swift-Tuttle Terminate Roman and Global Civilization? [ROME’S POPULATION CATASTROPHE: G

1 Did Comet HEINRICH-Swift-Tuttle Terminate Roman and Global Civilization? [ROME’S POPULATION CATASTROPHE: https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demografia_di_Roma] G. Heinsohn, January 2021 In the first millennium CE, the people of ROME built residential quarters, latrines, water pipes, sewage systems, streets, ports, bakeries etc., but only during Imperial Antiquity (1- 230s CE). No such structures were built during Late Antiquity (4th-6th/7th c.) or the Early Middle Ages (8th-930s CE). [See already https://q-mag.org/gunnar-heinsohn-the-stratigraphy- of-rome-benchmark-for-the-chronology-of-the-first-millennium-ce.html] Since the ruins of the 3rd c. CE lie directly beneath the primitive new structures that were built after the 930s CE (i.e., BEGINNING OF THE HIGH MIDDLE AGES), Imperial Antiquity belongs stratigraphically to the period from 700 to 930s CE. The steep decline in the population of Rome from 1.5 million to 650,000, dated in the diagram to "450" CE, must be accommodated archaeologically within Imperial Antiquity. This decline is due to the crisis caused by the Antonine Plague and Fires, the burning of Rome's State Archives (Tabularium), the Comet of Commodus before the rise of the Severan Emperors (190s-230s CE), and the invasion of Italy by proto-Hunnic Iazyges and proto-Gothic Quadi from the 160s to the 190s. The 160s ff. are stratigraphically parallel with the 450s ff. CE and its invasion of Italy by Huns and Goths. Stratigraphically, we are in the 860s ff. CE, with Hungarians and Vikings. The demographic collapse in the CRISIS OF THE 6th CENTURY (“553” CE in the diagram) is identical with the CRISIS OF THE 3rd C., as well as with the COLLAPSE OF THE 10th C., when Comet HEINRICH-Swift-Tuttle (after King Heinrich I of Saxony; 876/919-936 CE) with ensuing volcanos and floods of the 930s CE ) damaged the globe and Henry’s Roman style city of Magdeburg). -

TBM NEWSLETTER N°12 Your New TBM Newsletter !

If this message is not correctly displayed please click here TBM NEWSLETTER N°12 www.tbm.aero Your new TBM Newsletter ! EDITO "With the very fast turboprop aircraft, “connection” means that TBM owners and operators become more closely linked with their travel requirements – flying rapidly and efficiently to airports that are nearer to their final destinations. At Daher, our goal is to build on this cornerstone benefit of the TBM family, with continual enhancements to the aircraft itself and the service we provide. " Read more Nicolas CHABBERT NEWS A new Service Center for Croatia "Brings on the heat" on Model Year 2018 . Daher has selected Aero Standard, an EASA New features for 2018 production TBM 910s and Part 145 maintenance organization based at TBM 930s include the first electrically-heated Zadar International Airport, as the Croatia seats for an aircraft in its single-engine turboprop Service Center for the TBM aircraft (...) category (...) . PILOT PROFILE NETWORK PROFILE Ron Guynn Jim and Laura Penn AVEX TBM 910 SN1213 . The TBM Network is one of Daher’s strongest Jim and Laura Penn are husband and wife assets in ensuring world-class support for owners certified public accountants from Fort Worth, and operators of its very fast turboprop (...) Texas, USA. Jim is a founding partner of (...) 885 1,5M 54 TBM FLIGHT HOURS SERVICE CENTERS SUPPORT TECHNICAL DOCUMENTATION SUPPORT NEWS The value of our Network What's new ? Our Network of authorized TBM Service Centers Get the latest documentation update and TBM Distributors brings added value to Daher’s family of very fast aircraft: a fact that is SUPPORT CORNER recognized and highly appreciated every day by the worldwide TBM owner/operator The first G1000 NXi upgrade community. -

1 Making a Difference in Tenth-Century Politics: King

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository 1 Making a Difference in Tenth-Century Politics: King Athelstan’s Sisters and Frankish Queenship Simon MacLean (University of St Andrews) ‘The holy laws of kinship have purposed to take root among monarchs for this reason: that their tranquil spirit may bring the peace which peoples long for.’ Thus in the year 507 wrote Theoderic, king of the Ostrogoths, to Clovis, king of the Franks.1 His appeal to the ideals of peace between kin was designed to avert hostilities between the Franks and the Visigoths, and drew meaning from the web of marital ties which bound together the royal dynasties of the early-sixth-century west. Theoderic himself sat at the centre of this web: he was married to Clovis’s sister, and his daughter was married to Alaric, king of the Visigoths.2 The present article is concerned with a much later period of European history, but the Ostrogothic ruler’s words nevertheless serve to introduce us to one of its central themes, namely the significance of marital alliances between dynasties. Unfortunately the tenth-century west, our present concern, had no Cassiodorus (the recorder of the king’s letter) to methodically enlighten the intricacies of its politics, but Theoderic’s sentiments were doubtless not unlike those that crossed the minds of the Anglo-Saxon and Frankish elite families who engineered an equally striking series of marital relationships among themselves just over 400 years later. In the early years of the tenth century several Anglo-Saxon royal women, all daughters of King Edward the Elder of Wessex (899-924) and sisters (or half-sisters) of his son King Athelstan (924-39), were despatched across the Channel as brides for Frankish and Saxon rulers and aristocrats.