Feasibility Study for Vehicle Sharing in Charleston, South Carolina

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ohio Taxpayers and Consumers Press Release

For more information, contact: Laura Bryant, Enterprise Holdings [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE New Peer-to-Peer Car Rental Modernization Law Protecting Ohio Taxpayers and Consumers ST. LOUIS (July 23, 2019) – Enterprise Holdings – which owns the Enterprise Rent-A-Car, National Car Rental and Alamo Rent A Car brands – is pleased to support Ohio’s new car rental modernization law that was recently enacted on behalf of all taxpayers and consumers. House Majority Leader Bill Seitz and Senate Finance Committee Chair Matt Dolan spearheaded the transparent legislative process with a key stakeholder group comprised of the Ohio Department of Taxation, the Ohio Insurance Institute (OII), all major airports, and the U.S. car rental industry, including peer-to-peer companies. Consistent Standards & Regulations HB 166, which was signed into law by Ohio Governor Mike DeWine last week, not only defines consumer requirements (addressing insurance, pricing disclosures and safety recalls), but also confirms that peer- to-peer providers are categorized as “vendors” for tax purposes. This unambiguously takes the onus of collecting or remitting taxes off individuals renting their vehicles on peer-to-peer platforms – dispelling a myth often perpetuated by peer-to-peer companies about the double-taxation of vehicle owners. “My objective in working through this issue was two-fold,” said Rep. Seitz. “To establish clear standards for insurance coverage in these three-party transactions, and to ensure all peer-to-peer platforms that receive the end customer’s money are paying applicable state taxes as the facilitating vendor.” The new law also provides a step toward compliance with 1989 National Association of Attorneys General (NAAG) regulations requiring fair, honest and uniform consumer pricing and advertising standards in the car rental industry. -

Ready to Make a Reservation? You Have a Few Options to Suit Your Needs: Option 1 Option 2 Option 3

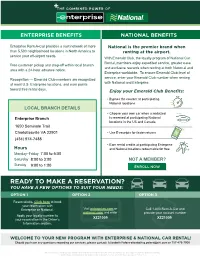

ENTERPRISE BENEFITS NATIONAL BENEFITS Enterprise Rent-A-Car provides a vast network of more National is the premier brand when than 5,500 neighborhood locations in North America to renting at the airport. service your off-airport needs. With Emerald Club, the loyalty program of National Car Rental, members enjoy expedited service, greater ease Free customer pickup and drop-off within local branch and exclusive rewards when renting at both National and area with a 24-hour advance notice. Enterprise worldwide. To ensure Emerald Club level of service, enter your Emerald Club number when renting Recognition — Emerald Club members are recognized with National and Enterprise. at most U.S. Enterprise locations, and earn points toward free rental days. Enjoy your Emerald Club Benefits: • Bypass the counter at participating National locations LOCAL BRANCH DETAILS • Choose your own car when a midsized is reserved at participating National locations in the US and Canada • Use E-receipts for faster returns • Earn rental credits at participating Enterprise Hours and National locations redeemable for free Monday–Friday Saturday NOT A MEMBER? Sunday ENROLL NOW READY TO MAKE A RESERVATION? YOU HAVE A FEW OPTIONS TO SUIT YOUR NEEDS: OPTION 1 OPTION 2 OPTION 3 Reservations. Click here to book your reservation with Enterprise or National. Visit enterprise.com or Call 1-800-Rent-A-Car and national.com and enter provide your account number Apply your loyalty number to your reservation in the Driver’s Information section. WELCOME TO YOUR NEW PROGRAM WITH ENTERPRISE & NATIONAL CAR RENTAL! Should you have any questions regarding our services, please contact: National, the “flag”, Emerald Aisle and Emerald Club are trademarks of Vanguard Car Rental USA LLC. -

Enterprise Rent-A-Car and Europcar Expand Strategic Alliance to Create the World’S Largest Car Rental Network

For more information, contact: Ned Maniscalco, Enterprise Rent-A-Car 314-512-5523, [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Enterprise Rent-A-Car and Europcar Expand Strategic Alliance To Create the World’s Largest Car Rental Network Partnership Expands Transatlantic Alliance Established in 2006 Between Europcar and National Car Rental and Alamo Rent A Car September 4, 2008 (St. Louis, Missouri) – Enterprise Rent-A-Car, North America’s largest car rental company, and Europcar, the number one car rental company in Europe, today announced they have enhanced their strategic alliance to include the Enterprise brand in North America, as well as the National Car Rental and Alamo Rent A Car brands that previously constituted the transatlantic partnership. Enterprise and Europcar have been working to formally expand the alliance ever since Enterprise’s purchase of the National and Alamo brands in North America in August 2007. With the addition to the new partnership of the Enterprise brand in North America, the alliance now offers a combined fleet of more than 1.2 million rental vehicles in more than 13,000 locations in 162 countries. The newly expanded partnership constitutes the largest car rental network in the world. The expanded alliance provides rental car coverage for customers traveling between each partner company’s areas of operations. Under the terms of the agreement, the partners will also take a coordinated approach to global corporate accounts, offering today’s companies and organizations the most extensive service provider network in the rental car industry anywhere in the world, complete with coordinated loyalty programs. The alliance is designed to leverage and develop traffic between North America and Europe: each year an estimated 12 million people travel across the Atlantic in either direction. -

City-Bike Maintenance and Availability

Project Number: 44-JSD-DPC3 City-Bike Maintenance and Availability An Interactive Qualifying Project Report Submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science By Michael DiDonato Stephen Herbert Disha Vachhani Date: May 6, 2002 Professor James Demetry, Advisor Abstract This report analyzes the Copenhagen City-Bike Program and addresses the availability problems. We depict the inner workings of the program and its problems, focusing on possible causes. We include analyses of public bicycle systems throughout the world and the design rationale behind them. Our report also examines the technology underlying “smart-bike” systems, comparing the advantages and costs relative to coin deposit bikes. We conclude with recommendations on possible allocation of the City Bike Foundation’s resources to increase the quality of service to the community, while improving the publicity received by the city of Copenhagen. 1 Acknowledgements We would like to thank the following for making this project successful. First, we thank WPI and the Interdisciplinary and Global Studies Division for providing off- campus project sites. By organizing this Copenhagen project, Tom Thomsen and Peder Pedersen provided us with unique personal experiences of culture and local customs. Our advisor, James Demetry, helped us considerably throughout the project. His suggestions gave us the motivation and encouragement to make this project successful and enjoyable. We thank Kent Ljungquist for guiding us through the preliminary research and proposal processes and Paul Davis who, during a weekly visit, gave us a new perspective on our objectives. We appreciate all the help that our liaison, Jens Pedersen, and the Danish Cyclist Federation provided for us during our eight weeks in Denmark. -

TSRC Section Cover Page.Ai

Susan Shaheen, Ph.D., Adam Cohen, Michael Randolph, Emily Farrar, Richard Davis, Aqshems Nichols CARSHARING Carsharing is a service in which individuals gain the benefits of private vehicle use without the costs and responsibilities of ownership. Individuals typically access vehicles by joining an organization that maintains a fleet of cars and light trucks. Fleets are usually deployed within neighborhoods and at public transit stations, employment centers, and colleges and universities. Typically, the carsharing operator provides gasoline, parking, and maintenance. Generally, participants pay a fee each time they use a vehicle (Shaheen, Cohen, & Zohdy, 2016). Carsharing includes three types of service models, based on the permissible pick-up and drop-off locations of vehicles. These are briefly described below: • Roundtrip - Vehicles are picked-up and returned to the same location. • One-Way Station-Based - Vehicles can be dropped off at a different station from the pick- up point. • One-Way Free-Floating - Vehicles can be returned anywhere within a specified geographic zone. This toolkit is organized into seven sections. The first section reviews common carsharing business models. The next section summarizes research on carsharing impacts. The remaining sections present policies for parking, zoning, insurance, taxation, and equity. Case studies are located throughout the text to provide examples of existing carsharing programs and policies. Carsharing Business Models Carsharing systems can be deployed through a variety of business models, described below: Business-to-Consumer (B2C) – In a B2C model, a carsharing providers offer individual consumers access to a business-owned fleet of vehicles through memberships, subscriptions, user fees, or a combination of pricing models. -

Andrew C. Taylor Executive Chairman Enterprise Holdings Inc

Andrew C. Taylor Executive Chairman Enterprise Holdings Inc. Andrew Taylor, who became involved in the automotive business more than 50 years ago, currently serves as Executive Chairman of Enterprise Holdings Inc., the privately held business founded in 1957 by his father, Jack Taylor. Enterprise Holdings operates – through an integrated global network of independent regional subsidiaries and franchises – the Enterprise Rent-A-Car, Alamo Rent A Car and National Car Rental brands, as well as more than 10,000 fully staffed neighborhood and airport locations in 100 countries and territories. Enterprise Holdings is the largest car rental company in the world, as measured by revenue and fleet. In addition, Enterprise Holdings is the most comprehensive service provider and only investment-grade company in the U.S. car rental industry. The company and its affiliate Enterprise Fleet Management together offer a total transportation solution, operating more than 2 million vehicles throughout the world. Combined, these businesses – accounting for $25.9 billion in revenue in fiscal year 2019 – include the Car Sales, Truck Rental, CarShare, Commute vanpooling, Zimride, Exotic Car Collection, Subscribe with Enterprise, Car Club (U.K.) and Flex-E-Rent (U.K.) services, all marketed under the Enterprise brand name. The annual revenues of Enterprise Holdings – one of America’s largest private companies – and Enterprise Fleet Management rank near the top of the global travel industry, exceeding many airlines and most cruise lines, hotels, tour operators, and online travel agencies. Taylor joined Enterprise at the age of 16 in one of the original St. Louis offices. He began his career by washing cars during summer and holiday vacations and learning the business from the ground up. -

Public Bicycle Schemes

Division 44 Water, Energy and Transport Recommended Reading and Links on Public Bicycle Schemes September 2010 Reading List on Public Bicycle Schemes Preface Various cities around the world are trying methods to encourage bicycling as a sustainable transport mode. Among those methods in encouraging cycling implementing public bicycle schemes is one. The public bicycle schemes are also known as bicycle sharing systems, community bicycling schemes etc., The main idea of a public bicycle system is that the user need not own a bicycle but still gain the advantages of bicycling by renting a bicycle provided by the scheme for a nominal fee or for free of charge (as in some cities). Most of these schemes enable people to realize one way trips, because the users needn’t to return the bicycles to the origin, which will avoid unnecessary travel. Public bicycle schemes provide not only convenience for trips in the communities, they can also be a good addition to the public transport system. Encouraging public bike systems have shown that there can be numerous short that could be made by a bicycle instead of using motorised modes. Public bike schemes also encourage creative designs in bikes and also in the operational mechanisms. The current document is one of the several efforts of GTZ-Sustainable Urban Transport Project to bring to the policymakers an easy to access list of available material on Public Bike Schemes (PBS) which can be used in their everyday work. The document aims to list out some influential and informative resources that highlight the importance of PBS in cities and how the existing situation could be improved. -

Andrew C. Taylor Executive Chairman Enterprise Holdings Inc

Andrew C. Taylor Executive Chairman Enterprise Holdings Inc. Andrew Taylor, who became involved in the automotive business more than 50 years ago, currently serves as Executive Chairman of Enterprise Holdings Inc., the privately held business founded in 1957 by his father, Jack Taylor. He also serves on the Crawford Group Board of Directors. Enterprise Holdings operates – through an integrated global network of independent regional subsidiaries and franchises – the Enterprise Rent-A-Car, Alamo Rent A Car and National Car Rental brands, as well as more than 9,500 fully staffed neighborhood and airport locations, including franchisee branches, in nearly 100 countries and territories. Enterprise Holdings is the largest car rental company in the world, as measured by revenue and fleet. In addition, Enterprise Holdings is the most comprehensive service provider and only investment-grade company in the U.S. car rental industry. The company and its affiliate Enterprise Fleet Management together offer a total transportation solution, operating nearly 1.7 million vehicles throughout the world and accounting for nearly $22.5 billion in revenue in fiscal year 2020. Combined, these businesses include the Car Sales, Truck Rental, CarShare, Commute vanpooling, Exotic Car Collection, Subscribe with Enterprise, Car Club (U.K.) and Flex-E-Rent (U.K.) services, all marketed under the Enterprise brand name, as well as travel management and other transportation services to make travel easier and more convenient for customers. The annual revenues of Enterprise Holdings – one of America’s largest private companies – and Enterprise Fleet Management rank near the top of the global travel industry, exceeding many airlines and most cruise lines, hotels, tour operators, and online travel agencies. -

Acquiring Zipcar: Brand Building in the Share Economy

Boston University School of Management BU Case Study 12-010 Rev. December 12, 2012 Acquiring Zipcar Brand Building in the Share Economy By Susan Fournier, Giana Eckhardt and Fleura Bardhi Scott Griffith, CEO of Zipcar, languished over his stock charts. They had something here, everyone agreed about that. Zipcar had shaken up the car rental industry with a “new model” for people who wanted steady access to cars without the hassle of owning them. Sales had been phenomenal. Since its beginning in 2000, Zipcar had experienced 100%+ growth annually, with annual revenue in the previous year of $241.6 million. Zipcar now boasted more than 750,000 members and over 8,900 cars in urban areas and college campuses throughout the United States, Canada and the U.K. and claimed nearly half of all global car-sharing members. The company had continued international expansion by purchasing the largest car sharing company in Spain. The buzz had been wonderful. Still, Zipcar’s stock price was being beaten down, falling from a high of $31.50 to a current trade at $8 and change (See Exhibit 1). The company had failed to turn an annual profit since its founding in 2000 and held but two months’ of operating cash on hand as of September 2012. Critics wondered about the sustainability of the business model in the face of increased competition. There was no doubt: the “big guys” were circling. Enterprise Rent-a-Car Co. had entered car sharing with a model of its own (See Exhibit 2). The Enterprise network, which included almost 1 million vehicles and more than 5,500 offices located within 15 miles of 90 percent of the U.S. -

Guideline for Bike Rental Transdanube.Pearls Final Draft

Transdanube.Pearls - Network for Sustainable Mobility along the Danube http://www.interreg-danube.eu/approved-projects/transdanube-pearls Guideline for bike rental Transdanube.Pearls Final Draft WP/Action 3.1 Author: Inštitút priestorového plánovania Version/Date 3.0, 23.11.2017 Document Revision/Approval Version Date Status Date Status 3.0 23/11/2017 Final draft xx.xx.xxxx final Contacts Coordinator: Bratislava Self-governing Region Sabinovská 16, P.O. Box 106 820 05 Bratislava web: www.region-bsk.sk Author: Inštitút priestorového plánovania Ľubľanská 1 831 02 Bratislava web: http://ipp.szm.com More information about Transdanube.Pearls project are available at www.interreg-danube.eu/approved-projects/transdanube-pearls Page 2 of 41 www.interreg-danube.eu/approved-projects/transdanube-pearls Abbreviations BSS Bike Sharing Scheme ECF European Cyclists´ Federation POI Point of Interest PT Public Transport Page 3 of 41 www.interreg-danube.eu/approved-projects/transdanube-pearls Table of content Contacts ..................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Bike Rental ................................................................................................................................................................ 5 Execuive summary ................................................................................................................................................. 5 1. Best practice examples from across -

Car Sharing Market In

CarSharing: State of the Market and Growth Potential By Chris Brown, March/April 2015 - Also by this author Though aspects of carsharing have existed since 1948 in Switzerland, it was only in the last 15 years that the concept has evolved into a mobility solution in the United States. Photo by Chris Brown. In that time, the carsharing market has grown from a largely subsidized, university research-driven experiment into a full-fledged for-profit enterprise, owned primarily by traditional car rental companies and auto manufacturers. Today, Zipcar (owned by Avis Budget Group), car2go (owned by Daimler), Enterprise CarShare and Hertz 24/7 control about 95% of the carsharing market in the U.S. Compared to car rental, total fleet size and revenues for carsharing remain relatively small. The “Fall 2014 Carsharing Outlook,” produced by the Transportation Sustainability Research Center at the University of California, Berkeley, reports 19,115 carsharing cars in the U.S., shared by about 996,000 members. Total annual revenue for carsharing in the U.S. is about $400 million, compared to the $24 billion in revenue for the traditional car rental market. Those carshare numbers have roughly doubled in five or six years, demonstrating steady growth but not an explosion. Yet technology, new transportation models, shifting demographics and changing attitudes on mobility present new opportunities. Is carsharing poised to take advantage? Market Drivers As carsharing in the U.S. is essentially consolidated under those four market leaders, they will inevitably be the drivers of much of that growth. Market watchers see one-way — or point-to-point carsharing — as a growth accelerator. -

Carsharing's Impact and Future

Carsharing's Impact and Future Advances in Transport Policy and Planning Volume 4, 2019, Pages 87-120 October 23, 2019 https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.atpp.2019.09.002 Susan Shaheen, PhD Adam Cohen Emily Farrar 1 Carsharing's Impact and Future Authors: Susan Shaheen, PhDa [email protected] Adam Cohenb [email protected] Emily Farrarb [email protected] Affiliations: aCivil and Environmental Engineering and Transportation Sustainability Research Center University of California, Berkeley 408 McLaughlin Hall Berkeley, CA 94704 bTransportation Sustainability Research Center University of California, Berkeley 2150 Allston Way #280 Berkeley, CA 94704 Corresponding Author: Susan Shaheen, PhD [email protected] 2 Carsharing’s Impact and Future ABSTRACT Carsharing provides members access to a fleet of autos for short-term use throughout the day, reducing the need for one or more personal vehicles. This chapter reviews key terms and definitions for carsharing, common carsharing business models, and existing impact studies. Next, the chapter discusses the commodification and aggregation of mobility services and the role of Mobility on Demand (MOD) and Mobility as a Service (MaaS) on carsharing. Finally, the chapter concludes with a discussion of how the convergence of electrification and automation is changing carsharing, leading to shared automated and electric vehicle (SAEV) fleets. Keywords: Carsharing, Shared mobility, Mobility on Demand (MOD), Mobility as a Service (MaaS), Shared automated electric vehicles (SAEVs) 1 INTRODUCTION Across the globe, innovative and emerging mobility services are offering residents, businesses, travelers, and other users more options for on-demand mobility. In recent years, carsharing has grown rapidly due to changing perspectives toward transportation, car ownership, business and institutional fleet ownership, and urban lifestyles.