Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Science to Survival: Using Virtual Exhibits to Communicate the Significance of Polar Heritage Sites in the Canadian Arctic

Open Archaeology 2016; 2: 209–231 Original Study Open Access Peter Dawson*, Richard Levy From Science to Survival: Using Virtual Exhibits to Communicate the Significance of Polar Heritage Sites in the Canadian Arctic DOI 10.1515/opar-2016-0016 Received January 20, 2016; accepted October 29, 2016 Abstract: Many of Canada’s non-Indigenous polar heritage sites exist as memorials to the Heroic Age of arctic and Antarctic Exploration which is associated with such events as the First International Polar Year, the search for the Northwest Passage, and the race to the Poles. However, these and other key messages of significance are often challenging to communicate because the remote locations of such sites severely limit opportunities for visitor experience. This lack of awareness can make it difficult to rally support for costly heritage preservation projects in arctic and Antarctic regions. Given that many polar heritage sites are being severely impacted by human activity and a variety of climate change processes, this raises concerns. In this paper, we discuss how virtual heritage exhibits can provide a solution to this problem. Specifically, we discuss a recent project completed for the Virtual Museum of Canada at Fort Conger, a polar heritage site located in Quttinirpaaq National Park on northeastern Ellesmere Island (http://fortconger.org). Keywords: Arctic; Heritage, Fort Conger, Virtual Reality, Computer Modeling, Education, Climate Change, Polar Exploration, Digital Archaeology. 1 Introduction Climate change and the emerging geopolitical significance of the Arctic have important implications for Canada’s polar heritage. In many Arctic regions, thawing permafrost, land subsidence, erosion, and flooding are causing irreparable damage to heritage sites associated with Inuit culture, historic Euro-North American exploration, whaling and the fur trade (Blankholm, 2009; BViikari, 2009; Camill, 2005; Hald, 2009; Hinzman et al., 2005; Morten, 2009; Stendel et al., 2008). -

Research Cruise Report: Mission HLY031

Research Cruise Report: Mission HLY031 Conducted aboard USCGC Healy In Northern Baffi n Bay and Nares Strait 21 July –16 August 2003 Project Title: Variability and Forcing of Fluxes through Nares Strait and Jones Sound: A Freshwater Emphasis Sponsored by the US National Science Foundation, Offi ce of Polar Programs, Arctic Division Table of Contents Introduction by Chief Scientist . 4 Science Program Summary . 6 Science Party List . 7 Crew List . 8 Science Component Reports CTD-Rosette Hydrography . 9 Internally recording CTD . 29 Kennedy Channel Moorings . 33 Pressure Array . 41 Shipboard ADCP . 47 Bi-valve Retrieval . 51 Coring . 55 Seabeam Mapping . 65 Aviation Science Report . 71 Ice Report . 79 Weather Summary . 91 Inuit Perspective . 95 Photojournalist Perspective . 101. Website Log . 105 Chief Scientist Log . 111 Recommendations . .125 Introduction Dr. Kelly Kenison Falkner Chief Scientist Oregon State University In the very early hours of July 17, 2003, I arrived at collected via the ship’s Seabeam system and the underway the USCGC Healy moored at the fueling pier in St. John’s thermosalinograph system was put to good use throughout Newfoundland, Canada to assume my role as chief scientist much of the cruise. for an ambitious interdisciplinary mission to Northern Part of our success can be attributed to luck with Mother Baffi n Bay and Nares St. This research cruise constitutes Nature. Winds and ice worked largely in our favor as we the inaugural fi eld program of a fi ve year collaborative wound our way northward. Our winds were generally research program entitled Variability and Forcing of moderate and out of the south and the ice normal to light. -

ARCTIC Exploration the SEARCH for FRANKLIN

CATALOGUE THREE HUNDRED TWENTY-EIGHT ARCTIC EXPLORATION & THE SeaRCH FOR FRANKLIN WILLIAM REESE COMPANY 409 Temple Street New Haven, CT 06511 (203) 789-8081 A Note This catalogue is devoted to Arctic exploration, the search for the Northwest Passage, and the later search for Sir John Franklin. It features many volumes from a distinguished private collection recently purchased by us, and only a few of the items here have appeared in previous catalogues. Notable works are the famous Drage account of 1749, many of the works of naturalist/explorer Sir John Richardson, many of the accounts of Franklin search expeditions from the 1850s, a lovely set of Parry’s voyages, a large number of the Admiralty “Blue Books” related to the search for Franklin, and many other classic narratives. This is one of 75 copies of this catalogue specially printed in color. Available on request or via our website are our recent catalogues: 320 Manuscripts & Archives, 322 Forty Years a Bookseller, 323 For Readers of All Ages: Recent Acquisitions in Americana, 324 American Military History, 326 Travellers & the American Scene, and 327 World Travel & Voyages; Bulletins 36 American Views & Cartography, 37 Flat: Single Sig- nificant Sheets, 38 Images of the American West, and 39 Manuscripts; e-lists (only available on our website) The Annex Flat Files: An Illustrated Americana Miscellany, Here a Map, There a Map, Everywhere a Map..., and Original Works of Art, and many more topical lists. Some of our catalogues, as well as some recent topical lists, are now posted on the internet at www.reeseco.com. -

Spatial Variation in Arctic Hare (Lepus Arcticus) Populations Around the Hall Basin

Spatial variation in Arctic hare (Lepus arcticus) populations around the Hall Basin Fredrik Dalerum1,2,3, Love Dalén2,4, Christina Fröjd5, Nicolas Lecomte6, Åsa Lindgren5, Tomas Meijer2,7, Patricia Pecnerova2,4, Anders Angerbjörn2 1 Research Unit of Biodiversity, Department of Biology of Organisms and Systems, University of Oviedo, Spain 2 Department of Zoology, Stockholm University, Sweden 3 Mammal Research Institute, Department of Zoology, University of Pretoria, South Africa 4 Department of Bioinformatics and Genetics, Swedish Museum of Natural History, Sweden 5 Swedish Polar Research Secretariat, Sweden 6 Canada Research Chair in Polar and Boreal Ecology and Centre d’Études Nordiques, Department of Biology, University of Moncton, Canada 7 Section for Wildlife Diseases, Swedish National Veterinary Institute, Travvägen 12A, 756 51 Uppsala, Sweden Published in Polar Biology, October 2017, Volume 40, Issue 10, pp 2113–2118 1 Abstract Arctic environments have relatively simple ecosystems. Yet, we still lack knowledge of the spatio- temporal dynamics of many Arctic organisms and how they are affected by local and regional processes. The Arctic hare (Lepus arcticus) is a large lagomorph endemic to high Arctic environments in Canada and Greenland. Current knowledge about this herbivore is scarce and the temporal and spatial dynamics of their populations are poorly understood. Here we present observations on Arctic hares in two sites on north Greenland (Hall and Washington lands) and one adjacent site on Ellesmere Island (Judge Daly Promontory). We recorded a large range of group sizes from 1 to 135 individuals, as well as a substantial variation in hare densities among the three sites (Hall land: 0 animals / 100 km2, Washington land 14.5-186.7 animals / 100 km2, Judge Daly Promontory 0.18-2.95 animals / 100 km2). -

The Morris Bugt Group (Middle Ordovician - Silurian) of North Greenland and Its Correlatives

The Morris Bugt Group (Middle Ordovician - Silurian) of North Greenland and its correlatives M. Paul Smith, Martin Sønderholm and Simon J. Tul! The Morris Bugt Group, originally proposed in western North Greenland, is now extendcd across the whole of North Greenland. One new formation, the Kap Jackson Formation, is described; it includes two members, the Gonioceras Bay and Troedsson Cliff Members, which correspond to earlier formations of the same names. In the Washington Land - western Peary Land region the group comprises the Kap Jackson, Cape Calhoun and Aleqatsiaq Fjord Formations. The Børglum River and Turesø Formations of the Peary Land - Kronprins Christian Land region are here added to the group. New data on the age of the formations based on conodont biostratigraphy are given, and correlations with Arctic Canada, East Greenland and Svalbard are discussed. M. P. S., Department of Earth Sciences, University of Cambridge, Downing Street, Cambridge CB23EQ, England. Present address: Geologisk Museum, øster Voldgade 5-7, DK-1350 København K, Denmark. M. S., Grønlands Geologiske Undersøgelse, øster Voldgade 10, DK-1350 København K, Denmark. S. J. T., Department ofGeology, University ofNoccingham, University Park, Notting ham NG72RD, England. Present address: Chapman & Hall, Il New Felter Lane, London EC4P 4EE, England. The Monis Bugt Group was erected by Peel & Hurst three members by Sønderholm & Harland (in prep.) (1980) to encompass the Gonioceras Bay, Troedsson who give full formal descriptions af these members. The Cliff, Cape Calhoun and Aleqatsiaq Fjord Formations. lower member of the Aleqatsiaq Fjord Formation cone These formations were originally described from Wash lates with the upper part of the Børglum River Forma ington Land (Troedsson, 1926, 1928; Koch, 1929a,b; tion. -

Canada Topographical

University of Waikato Library: Map Collection Canada: topographical maps 1: 250,000 The Map Collection of the University of Waikato Library contains a comprehensive collection of maps from around the world with detailed coverage of New Zealand and the Pacific : Editions are first unless stated. These maps are held in storage on Level 1 Please ask a librarian if you would like to use one: Coverage of Canadian Provinces Province Covered by sectors On pages Alberta 72-74 and 82-84 pp. 14, 16 British Columbia 82-83, 92-94, 102-104 and 114 pp. 16-20 Manitoba 52-54 and 62-64 pp. 10, 12 New Brunswick 21 and 22 p. 3 Newfoundland and Labrador 01-02, 11, 13-14 and 23-25) pp. 1-4 Northwest Territories 65-66, 75-79, 85-89, 95-99 and 105-107) pp. 12-21 Nova Scotia 11 and 20-210) pp. 2-3 Nunavut 15-16, 25-27, 29, 35-39, 45-49, 55-59, 65-69, 76-79, pp. 3-7, 9-13, 86-87, 120, 340 and 560 15, 21 Ontario 30-32, 40-44 and 52-54 pp. 5, 6, 8-10 Prince Edward Island 11 and 21 p. 2 Quebec 11-14, 21-25 and 31-35 pp. 2-7 Saskatchewan 62-63 and 72-74 pp. 12, 14 Yukon 95,105-106 and 115-117 pp. 18, 20-21 The sector numbers begin in the southeast of Canada: They proceed west and north. 001 Newfoundland 001K Trepassey 3rd ed. 1989 001L St: Lawrence 4th ed. 1989 001M Belleoram 3rd ed. -

The Nares 2001 Geoscience Project: an Introduction

Polarforschung 74 (1-3), 1 – 7, 2004 (erschienen 2006) The Nares 2001 Geoscience Project: An Introduction by Ian D. Reid1, H. Ruth Jackson2 and Franz Tessensohn3 Abstract: Nares Strait forms a rather straight set of narrow marine channels Onshore geological evidence, however, implied that no more between Greenland and the Canadian Arctic Islands. Since 1982, the Nares than 25 km of offset had taken place (MAY R & DE VRIES 1982), Strait dilemma forms a classical case of conflict between plate tectonics and regional geology without obvious solution. Plate tectonics postulated a sinis- and this discrepancy has given rise to a long-standing contro- tral continental transform through the strait, whereas regional geological versy. The situation is complicated by the fact that in addition mapping results could not find evidence for the required offsets. Between to the postulated Wegener Fault two more important tectonic 1982 and 2000 new data were gathered in northern Baffin Bay and on either side of the Strait, yet the Strait itself had still not been investigated. We report boundaries are mapped to lie under the waters of the northern on an expedition carried out in 2001 in the previously unexplored water co- part of Nares Strait (Fig. 1). The question: Did Greenland drift vered area. In spite of the difficult ice conditions, we gathered new marine, along Nares Strait? has been argued for more than 90 years, aeromagnetic and geological data relevant to the problem. The results are AWES presented in this volume together with compilations of the related geological and was the subject of a major symposium in 1980 (D & and geophysical data bases. -

Adolphus Washington Greely (1844-1935) Adolphuswashington Greely Became a Worldcelebrity Officer

150 ARCTIC PROFILES Adolphus Washington Greely (1844-1935) AdolphusWashington Greely became a worldcelebrity officer. Here he fell under the spell of Captain Henry W. almost overnight in 1884 when the six survivors of the Lady Howgate, a Signal Service officer who was an enthusiast for Franklin Bay Expedition under his leadership were rescued arctic exploration and who opened his extensivelibrary of arc- from starvation in the Arctic. Yet he was far more than the tic literature to the younger officer. It was through this chain central figure of one tragic expedition. Explorer, soldier, of events that Greely was inspiredto a deep interest in leading scientist, and author, Greely was respected as an international an arctic expedition. He hadseveral motives: to visit a strange authority on polar science from the 1880s until his death 50 and romantic part of the world, to study the physical condi- years later. tions of theFar North, to conduct signaling experiments under Born in Newburyport, Massachusetts, in 1844, Greely vol- severe weather conditions, and also, perhaps, to make a name unteered for Civil War service in the Union Army before he for himself that would help his promotion. was 18. He was grievously wounded at Antietam in 1862, but In October 1879 ai International Polar Conference held in returned to active dutythe following spring as anofficer of the Hamburg agreed ona common program of meteorological and U.S. Colored Infantry, made up of free black soldiers. When otherphysical observations by expeditionssupported by a the war ended he heldthe brevet rank of captainof volunteers dozen countries, all to be placed as far toward the top of the and decided on service in the regular army as his career. -

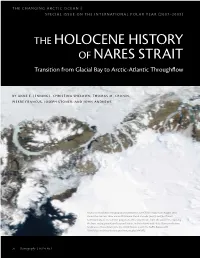

The Holocene History of Nares Strait Transition from Glacial Bay to Arctic-Atlantic Throughflow

THE CHANGING ARCTIC OCEAN | SpECIAL ISSUE ON THE IntERNATIONAL POLAR YEAr (2007–2009) THE HOLOCENE HISTORY OF NARES STRAIT Transition from Glacial Bay to Arctic-Atlantic Throughflow BY AnnE E. JEnnINGS, CHRISTINA SHELDON, THOMAS M. CRONIN, PIERRE FRANCUS, JOSEPH StONER, AND JOHN AnDREWS Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) image from August 2002 shows the summer thaw around Ellesmere Island, Canada (west), and Northwest Greenland (east). As summer progresses, the snow retreats from the coastlines, exposing the bare, rocky ground, and seasonal sea ice melts in fjords and inlets. Between the two landmasses, Nares Strait joins the Arctic Ocean (north) to Baffin Bay (south). From http://visibleearth.nasa.gov/view_rec.php?id=3975 26 Oceanography | Vol.24, No.3 ABSTRACT. Retreat of glacier ice from Nares Strait and other straits in the Nares Strait and the subsequent evolu- Canadian Arctic Archipelago after the end of the last Ice Age initiated an important tion of Holocene environments. In connection between the Arctic and the North Atlantic Oceans, allowing development August 2003, the scientific party aboard of modern ocean circulation in Baffin Bay and the Labrador Sea. As low-salinity, USCGC Healy collected a sediment nutrient-rich Arctic Water began to enter Baffin Bay, it contributed to the Baffin and core, HLY03-05GC, from Hall Basin, Labrador currents flowing southward. This enhanced freshwater inflow must have northern Nares Strait, as part of a study influenced the sea ice regime and likely is responsible for poor -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. ProQuest Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMT UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE HOME ONLY LONG ENOUGH: ARCTIC EXPLORER ROBERT E. PEARY, AMERICAN SCIENCE, NATIONALISM, AND PHILANTHROPY, 1886-1908 A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By KELLY L. LANKFORD Norman, Oklahoma 2003 UMI Number: 3082960 UMI UMI Microform 3082960 Copyright 2003 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Titie 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 c Copyright by KELLY LARA LANKFORD 2003 All Rights Reserved. -

Curriculum Vitae: Anne E

CURRICULUM VITAE: ANNE E. JENNINGS Research Scientist III; INSTAAR Fellow Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research University of Colorado Boulder, CO 80309-450 Phone: 303-492-7621 Fax: 303-492-6388 Email: [email protected] Education 1989 PhD., Geology, University of Colorado, Boulder. 1986 M.Sc., Geology, University of Colorado, Boulder. 1980 B.S., Geology, Duke University. Professional and Educational Experience January 1, 2000- Present: Fellow, INSTAAR, University of Colorado, Boulder. Editor, Arctic, Antarctic and Alpine Research, October 2004 to present Research Interests Research interests include; 1) Holocene paleoceanography and sea-ice history of Greenland and Iceland shelves 2) glacial-marine sedimentation: stratigraphy, paleoenvironments, and glacial history on high latitude shelves (East Greenland, West Greenland, and Iceland); and 3) Modern foraminiferal distributions and ecology on high latitude shelves (Greenland, and Iceland). 4) Sub-ice shelf sedimentation and sub-ice shelf foraminifera in the Petermann Fjord, NW Greenland. 5) Baffin Bay and Labrador Sea LGM and deglaciation. Recent and Current International Collaboration Aslaug Geirsdóttir, Univ. of Iceland Colm O’Cofaigh, Durham University, UK Paul Knutz, GEUS, Denmark Marit-Solveig Seidenkrantz, Aarhus Univ., Claude Hillaire-Marcel, GEOTOP, CA DK Christof Pearce, Stockholm University, SW Guillaume St-Onge, Laval University, Quebec Karen Luise Knudsen, Aarhus Univ. DK Canada Alix Cage, Keele Univ. UK Anna Pienkowski, UNIS, Norway Teaching and Thesis Committees: 2017: Honors thesis committee for Blythe Befus. Geological Sciences. 2016: Honors thesis committee for Anna Klein, Geological Sciences. 2014: Member of Dissertation committee for Whitney Doss and member of MS committee for Hannah Grist, Geological Sciences. 2012-2014: Member of Disstertation committee for Ursula Quillmann. -

An Arctic Execution: Private Charles B

ARCTIC VOL. 64, NO. 4 (DECEMBER 2011) P. 399 – 412 An Arctic Execution: Private Charles B. Henry of the United States Lady Franklin Bay Expedition 1881 – 84 GLENN M. STEIN1 (Received 6 January 2011; accepted in revised form 11 April 2011) ABSTRACT. Private Charles B. Henry, of the United States Lady Franklin Bay Expedition, was put to death by a summary military execution on 6 June 1884, at Camp Clay, near Cape Sabine, Ellesmere Land, in the High Arctic. An execution is an extremely rare event in Arctic and Antarctic history. Shrouded in mystery for over 125 years, Henry’s execution has been told in two contradicting accounts. By considering the actions of key persons, presenting new details, and identifying related artifacts for the first time, the author concludes that the lesser-known account is likely more accurate and that the participants in the execution had their reasons for not sharing the actual version publicly until many years later. Key words: Lady Franklin Bay Expedition, Charles B. Henry, Adolphus Greely, Brainard, Cape Clay, execution, International Polar Year expedition RÉSUMÉ. Le soldat Charles B. Henry, de l’expédition américaine de la baie Lady Franklin, a été mis à mort lors d’une exécution militaire sommaire le 6 juin 1884, au camp Clay, près du cap Sabine, Ellesmere Land, dans l’Extrême-Arctique. Les exécutions se font extrêmement rares dans l’histoire de l’Arctique et de l’Antarctique. Entourée de mystère pendant plus de 125 ans, l’exécution du soldat Henry a été racontée dans le cadre de deux récits contradictoires.