Multicultural Mediations, Developing World Realities: Indians, Koreans and Manila’S Entertainment Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revista Filipina • Primavera 2019 • Volumen 6, Número 1 Revista Filipina Primavera 2019 Volumen 6 • Número 1

Revista Filipina • Primavera 2019 • volumen 6, número 1 Revista Filipina Primavera 2019 volumen 6 • número 1 Revista semestral de lengua y literatura hispanofilipina Segunda etapa ISSN: 1496-4538 RF Fundada en 1997 por Edmundo Farolán Dirigida desde 2017 por Edwin Lozada http://revista.carayanpress.com Derechos reservados / Copyright © 2019 Revista Filipina 1 1 Revista Filipina • Primavera 2019 • volumen 6, número 1 CRÉDITOS Revista Filipina. Revista semestral de lengua y literatura hispanofilipina es una publicación electrónica internacional fundada en Vancouver por Edmundo Farolán en 1997. En una primera época de forma tri- mestral, desde 2013 se inicia una segunda época de aparición semestral. Asociada a la editorial Carayan Press de San Francisco, California, Edwin Lozada dirige la publicación al cumplirse los veinte años de existencia continuada e ininterrumpida desde 2017. La revista publica un volumen anual en dos números semestrales (primavera-invierno) con las siguientes secciones regulares: ensayos, artículos y notas, reseñas y comentarios bibliográficos y biblioteca. También dedica espacio a la actualidad del Filipinismo mundial y la bibliofilia filipina. Atiende a cuatro objetivos principales: 1) Foro de reflexión y expresión filipino en lengua española; 2) Estudios académicos de Filipinismo, con especial atención a la lengua española en Filipinas y la literatura hispanofilipina; 3) Revista de bibliografía Filipiniana; y 4) Repositorio histórico y actual de literatura y crítica filipinas. Revista Filipina se encuentra registrada -

Pssst Aug 23 2012 Issue

PULITIKA • SHOWBIZ • SPORTS • SCANDAL • TSISMIS Carmina at Zoren magpapakasal na Vol.Vol. I No. I No.165 160 SHOWBIZ Vol. I No. 164 this year PAHINA 7 Tom Cruise, nalungkot Zoren Legaspi at No.1 sa pagkamatay ng Carmina Villaroel direktor nya sa ISSN-2244-0593 HOLLYWOOD “Top Gun” BITZ PAHINA 6 www.pssst.com.ph Tom Cruise www.pssst.com.phwww.pssst.com.ph TODAY’S WEATHER #1 in News and Journalism (Aug. 19, 2012) Variable clouds with scattered www.pssst.com.ph MIYERKULES • AGOSTO 01, 2012 thunderstorms, chance of rain 60%. HUWEBESwww.pssst.com.ph • AGOSTO 23, 2012 -- Top MIYERKULES Blogs Philippines • AGOSTO 01, 2012 24-29°C Lotto Results • 6/55 GRANDLOTTO 24 03 42 36 35 06 6/45 MEGALOTTO 28 17 20 10 19 31 1$ = P42.318 MASAYANG ka-bonding ni late DILG Secretary Jesse Robredo ang mga bata sa Naga noong alkalde pa ito ng lungsod. (Naga-LGU file photo) ‘SALAMAT SA SHOWBIZ PAHINA 7 MAGANDANG NEWS EHEMPLO’ PAHINA 3 IBA PANG BALITA •MAG-IINA MINASAKER SA VALENZUELA; SUSPEK METRO NEWS NEWS PAHINA 2 PAHINA 8 NAGPAKAMATAY DIN •ALBAY NAGBIGAY PUGAY KAYSHOWBIZ ROBREDO PAHINA 6 NEWS www.pssst.com.ph 2 HUWEBES • AGOSTO 23, 2012 Plane wreckage, isa Albay, nagbigay pang piloto naiahon na NAIAHON na umano ng umano makumpirma ang pag- mga tauhan ng Civil Avia- kakakilanlan nito. tion Authority of the Phil- Samantala, ipagpapatu- ippines mula sa ilalim ng loy umano ngayong araw ang dagat ang plane wreckage search and retrieval operation pugay kay Robredo kung saan natagpuan ang para sa katawan ng isa pang katawan ni Department of piloto. -

Hospitalization Will Be Free for Poor Filipinos

2017 JANUARY HAPPY NEW YEAR 2017 Hospitalization will be Pacquiao help Cambodia free for poor Filipinos manage traffic STORY INSIDE PHNOM PENH – Philippine boxing icon Sena- tor Manny Pacquiao has been tapped to help the Cambodian government in raising public aware- ness on traffic management and safety. Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen made the “personal request” to Pacquiao in the ASEAN country’s bid to reduce road traffic injuries in the country. MARCOS continued on page 7 WHY JANUARY IS THE MONTH FOR SINGLES STORY INSIDE Who’s The Dancer In The House Now? Hannah Alilio performs at the Christmas Dr. Solon Guzman seems to be trying to teach his daughters Princess and Angelina new moves at Ayesha de Guzman and Kayla Vitasa enjoy a night out at the party of Forex Cargo. the Dundas Tower Dental and Milton Dental Annual Philippine Canadian Charitable Foundation / AFCM / OLA Christmas party. Christmas Party. Lovebirds Charms Friends Forex and THD man Ted Dayno is all smiles at the Forex Christmas dinner with his lovely wife Rhodora. Star Entertainment Circle’s Charms relaxes prior to the start of the Journalist Jojo Taduran poses with Irene Reeder, wife Star Circle Christmas Variety Show. of former Canada Ambassador to the Phl Neil Reeder. JANUARY 2017 JANUARY 2017 1 2 JANUARY 2017 JANUARY 2017 Paolo Contis to LJ Reyes: “I promise to protect your Honey Shot heart so it will never get hurt ever again” Paolo Contis shares the sweetest message to LJ Reyes for her birthday on December 25. Alden and Maine in In his Insta- gram account a TV series, finally the actor poured his heart out Every popular love team has their own as he shared a TVCs (a lot of them), big screen projects collage of LJ’s and a television series. -

Download (288Kb)

IR – PERPUSTAKAAN UNIVERSITAS AIRLANGGA 69 WORKS CITED 6 Theory Media. 2NE1's Sandara Park Reveals Her Epic 'Vegeta' Hairstyle! 7 September 2011. 15 June 2015. <http://www.allkpop.com/article/2011/09/2ne1s-sandara-park-reveals-her- epic-vegeta-hairstyle>. Asia Society. Women's Role in Contemporary Korea. 2013. 12 June 2015. <http://asiasociety.org/womens-role-contemporary-korea>. Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble. London: Routledge, 2007. Cirlot, J. E. A Dictionary of Symbols. London: Routledge, 1971. England, Dawn Elizabeth, Lara Descarte and Melissa A. Collier-Meek. "Gender Role Portrayal and the Disney Princesses." Sex Roles (2011). Ferber, Michael. A Dictionary of Literary Symbols. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007. Fiske, John. Television Culture. New York: Routledge, 1999. Free Hosting Guru. Confucianism. 2013. 12 June 2015. <http://confucianism.freehostingguru.com/>. Funimation Productions. Vegeta. 2003. 12 June 2015. <http://www.dragonballz.com/characters/vegeta>. SKRIPSI THE REPRESENTATION OF FEMININITY ... AFIF LINOFIAN IR – PERPUSTAKAAN UNIVERSITAS AIRLANGGA 70 Giannetti, Louis. Understanding Movies. London: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2008. Hall, James. Illustrated Dictionary of Symbols in Eastern and Western Art. Colorado: Westview Press, 1995. In, Soo Nam. South Korean Women Get Even, At Least in Number. 1 July 2013. 6 May 2015. <http://blogs.wsj.com/korearealtime/2013/07/01/south-korean- females-get-even-at-least-in-number/>. Ingleheart, R. Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic, and Political Changes in 43 Societies. New Jersey: Princeton, 1997. Kim, Jong Mi. "Is ‗the Missy‘ a New Femininity?" New Femininities: Postfeminism, Neoliberalism and Subjectivity (2011): 147-158. Koo, Jhon H and Andrew C Nahm. An Introduction to Korean Culture. Seoul: Hollym Corporation, 2000. -

On the Future Directions of Korean Culture Studies for Teaching and Research: a Suggestion from New Zealand 15

2012 philippine korean studies symposium proceedings 1 This proceedings is a collection of the papers presented in the 2012 Philippine Korean Studies Symposium held on February 24, 2012 at the Balay Kalinaw, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City. This was organized by the UP Department of Linguistics and Korea Foundation. Copyright © 2012 by the UP Department of Linguistics College of Social Sciences and Philosophy University of the Philippines Diliman, Quezon City ALL RIGHTS RESERVED 2012 Philippine Korean Studies Symposium Committee Members: Mary Ann Bacolod, PhD (UP Department of Linguistics Chairperson) Kyungmin Bae Farah Cunanan Mark Rae De Chavez Jay-Ar Igno Michael Manahan Victoria Vidal Logo by Faith De Leon and Michael Manahan. 2 contents Introduction 6 Message UPD President UPD Chancellor KF President The Embassy of Republic of Korea Minister Department of Linguistics Chairperson Plenary Keynote Speech The Advantages of Comparative Approaches in Korean Studies Hong-key Yoon Session 1: Overview on Korean Studies Korean Development Model and the Entailment to the Philippines Seok-choon Lew Hallyu, Hype and the Humanities: The Impact of the Korean Wave on Korean Studies Roald Maliangkay Effective Liaison of Korean Language Education and Korean Studies – Building Korean Language Pedagogic Contents and Korean Studies Hang-rok Cho Reactions Fernando Nakpil-Zialcita Jose Wendell Capili Pamela C. Constantino Session 2: Panel Discussion on Korean Language Education- The Current Status and Future Development of Korean Language -

Philippines May Lose Trade Perk

MAY 2018 Philippines may lose trade perk As Philippines reaches middle income status, European exports may be subject to tariffs MANILA - The Philippines may (EU) which is aimed at poorer middle income status in 2019. Philippine products to enter the region at soon lose its eligibility for a trade nations, in view of a report that zero tariff. perk from the European Union says the country may reach upper Under current rules, the EU’s prefer- TRADE PERK ential trade scheme allows thousands of continued on page 12 Onlookers could not help Spotlight but say that Marian looks AVENIDA RIZAL, 1956 more gorgeous these days, which she would grateful- ly acknowledge with the sweetest smile. Careful not to take the thunder away from the movie’s leads, she humbly said, “I’m here to support the people I love. Barbie who is with me in ‘Sunday Pinasaya,’ Derrick, and of course Direk Lou- ie, our director [in the noontime show], whom I love so dearly. Ex- cited siyempre akong makita yung movie, especially since it was shot in Italy. ‘Di ba kagagaling lang namin sa Europe,” she enthused. The European vacation was SHUT UP another unforgettable experience SUPREME COURT TELLS ROBEREDO, MARCOS for Marian and her family. “We really had fun everywhere we went, visiting most of them for the first time. Nag-enjoy rin si Zia and that’s what’s important—yung JADINE - JADAONE Issue : ma-enjoy niya ‘yung mga lugar na pinupuntahan namin and all the activities we do. Saka ang sarap “Other People Make it Bigger” niyang bihisan kasi ang cute,” Marian dotingly giggled. -

VICE President KONTRABIDAS

2018 FEBRUARY NEW Kapuso Loveteam? Andre & Klea ANNULMENT OK lo PHILIPPINES - The House of Rep- Under the bill, marriage annulments veteam? resentatives has approved a proposed law that eliminates the costly judicial ANNULMENT process for marriage annulment. continued on page 25 JADINE movie ‘Never Not love you’ not happening? Am-FILIPINO star in HollYwood Dengue Vaccine Versace Assassination TV Show Side Effects PEOPLE Who use Blown out of EMOJIS a LOT have More sex proportion VICE President Office will DISaPPear Binibining Pilipinas 4th year longest FILIPINOS TOP on Binibining Pilipinas contestants like Agatha Romero (TOP)and crossover This photo, taken on April 4, 2016, shows a nurse showing vials of beauty queen Catriona Gray (ABOVE) the dengue vaccine Dengvaxia, developed by French medical giant are ready to represent the Philippines. Sanofi Pasteur, during a vaccination program at an elementary school in Metro Manila. A group of physicians and scientists has issued a statement expressing dismay at how the controversy surrounding the an- PORNHUB ti-dengue Dengvaxia vaccine has started to WHY showbiz need GOOD “erode” public confidence in the country’s vaccination programs. The statement, which was emailed to media outfits, was signed by 58 doctors, in- cluding former Health secretaries Esparan- KONTRABIDAS za Cabral and Manuel Dayrit. “The unnecessary fear and panic, largely brought about by the imprudent language reduce and unsubstantiated accusations by persons whose qualifications to render any expert opinion on the matter are questionable, at best, have caused many parents to resist having their children avail of life saving STRESS vaccines that our government gives,” the SEX statement read. -

Umuunlad Ang Turismo Handa Tayo Para Sa Paglago Ng Turismo

Alaala ng Eid kapag Bagong aral mula Herrera taas-noo pa rin Ramadan sa pagbaha sa bilang ‘Olympian’ Pilipinas PAGE 3 PAGE 4 PAGE 8 Salawikain Ang pagiging manunulat o makata ko ay hindi katakataka, o kaya ay biniyayaan ako ng isang kapang- yarihan. Ito ay dahil sa pagsisikap at mahirap na pamu- muhay, pagdurusa, kalungkutan, kasiphayuan, kagutu- man, pagkamuhi, kaligayahan, pagkaawa — ang lahat ng mga ito ang dahilan ng pagiging manunulat ko. — Carlos Bulosan (1911-1956), Pilipinong manunulat sa Amerika na nais bumalik sa Pilipinas pero ‘di nagawa dahil sa pumanaw doon. Pinoy Xtra Linggo, Agosto 19, 2012 [email protected] Umuunlad ang turismo Handa tayo para sa paglago ng turismo. Kung hindi tayo handa ngayon, kelan pa? Napako na tayo sa 3-milyong mga turista nitong nakaraang tat- long dekada at Ang Huma island napag-iwanan na tayo ng lahat. Rosa S. Ocampo at Aimee Flores | Pinoy Xtra Vic Alcuaz AKAKALULA ang bilyon- integrated casino resorts na sinasabing magig- he, mga ferry at iba-ibang tourist attractions. Asya at iba pa. Isa rin sa hangad ng bilyong dolyar na puhunan ing Las Vegas ng Asya. Sa unang bahagi ng Bahagi ito ng tourism plan ng Pilipinas Kagawaran ng Turismo ang mga turistang sa turismo — mula Luzon isang taon ay bubuksan ang integrated casi- na mapadali at maging maayos ang mga Arabo dahil isa sila sa pinakamalalaking hanggang Mindanao, mula no resort na Solaire, pag-aari ng Bloomberry biyahe sa buong Pilipinas bukod pa sa gumastos sa buong mundo. sa mga hotels hanggang sa Resorts and Hotels na pinamumunuan ng pagkakaroon ng maraming uri ng akomo- Laging dumadalo ang Pilipinas sa Nmga paliparang himpapawid — na ngayon negosyanteng si Enrique Razon, Jr. -

CARDINAL Tagle the First Filipino Pope Marriage Is Good for the Heart

ittle anila LFEB. - MARCHM. 2013Confidential CARDINAL Tagle The First Filipino Pope Marriage is Good for the Heart Sleep-deprived should watch their Portion Sizes Why women care more about their looks than their health PH has Good Disaster Laws - UN Dirty Money Unfortunately, Weak Governance make these Laws Useless MANILA, Philippines - The “Legislation is insufficient unless It also noted that the Philippine from PHL Philippines has good laws on it is supported by strong political will constitution and political system allow MANILA, Philippines - This made the disaster risk reduction but weak local to ensure implementation,” the report local executives to enforce policies that Philippines place sixth in a ranking of governance tends to render these dubbed “Disaster-induced internal will keep the public out of disaster- countries that are the biggest sources of useless, the United Nations said. displacement in the Philippines” said. prone areas. financial outflow attributed to corruption, tax A new UN report released found The report lauded the Philippine “Yet the combination of high poverty evasion, smuggling and other illegal activities, that poor urban governance led to Disaster Risk Reduction and DISASTER ineffective building codes and land use Management Act of 2010 as a possible DIRTY MONEY continued on page 22 planning at the local level. template for other countries. continued on page 13 PHL Not Popular to Int’l Investors Our Man in the Consulate MANILA, Philippines - British Ambassador business seminar and networking event. to the Philippines Stephen Lillie called on the He added that various business groups had Philippine government on Tuesday to “adjust” raised with the Philippine government the a law limiting foreign ownership of businesses need to create a better business environment in to allow more investments into the country, the country. -

Perro Berde : Revista Cultural Hispano-Filipina. Núm. 6, 2016

Not sale. for Totally free. PER RO BE RDERevista Cultural Hispano-Filipina VI This magazine has been conceived to Esta es una revista que se distribuye be distributed for free by the Embassy de forma gratuita por la Embajada of Spain in the Philippines and the de España en Filipinas y el Instituto Instituto Cervantes de Manila, so that Cervantes de Manila quedando así es- its sale is strictly prohibited. The said trictamente prohibida su venta. Dichas institutions are not responsible for the instituciones no se hacen responsables opinions expressed by the authors or de las opiniones vertidas ni de la ve- the veracity of the events narrated in racidad de los hechos narrados en esta this publication. publicación. PER ROREVISTA CULTURAL HISPANO- FILIPINA BE Cover illustration by Ines Agathe Maud. 2016RDEVI him. He caresses us and we never know gico al que debe su nombre: “¡Qué ex- why—but not when we offer to caress traño animal es el hombre! Nunca está PERRO him. When we devote ourselves most PERRO en lo que tiene delante. Nos acaricia sin to him he drives us away and beats us. que sepamos por qué y no cuando le BERDE There is no way of knowing what he BERDE acariciamos más, y cuando más a él nos wants; if indeed he knows it himself. “ rendimos nos rechaza o nos castiga. No 6 We humans, who look out for our 6 hay modo de saber lo que quiere, si es Perro Berde, fortunately know what we que lo sabe él mismo.” want. We keep on protecting our rara The avis for being different and in some la Los humanos que nos ocupamos de ways, for being unique. -

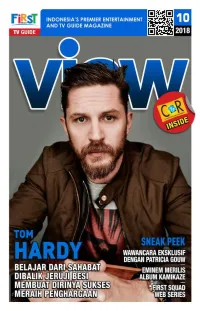

View 201810.Pdf

MY TOP 10 JURASSIC PARK DIVA Film ini bercerita tentang seorang pengusaha kaya bernama John Hammond yang begitu terobsesi MY dengan dunia Dinosaurus. Ia pun ingin membuka taman di pulau Isla Nubar dan melakukan rekayasa TOP genetika dengan memadupadankan DNA Dinosaurus yang kemudian dilengkapi dengan berbagai DNA hewan lainnya. WOLVES AND WARRIORS ANIMAL PLANET “Wolves and Warriors” menampilkan kelompok Lockwood Animal Rescue Center atau yang 10FAVORITE dikenal dengan LARC, untuk menyelamatkan para PROGRAMS serigala dari situasi berbahaya. A DOG’S WORLD RUGRATS IN PARIS : NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC WILD THE MOVIE HBO FAMILY Pada acara ini, kita akan diajak untuk Pada film kali ini cerita mengenal lebih akan berfokus pada jauh tentang dunia karakter Chuckie, anjing. Dimana kita dimana Chuckie akan mendapatkan sangat merindukan pengetahuan sosok seorang ibu baru tentang karena ia merupakan kemampuan anjing seorang anak piatu. seperti kemampuan Disatu sisi, sang ayah mendeteksi kanker, juga menginginkan memprediksi kejang-kejang, dan membantu kebahagiaan bagi anaknya, dimana ia ingin berbagai hal lain dalam kehidupan manusia Chuckie memiliki ibu dan mendapatkan kasih seperti memberikan perlindungan. sayang ibu seperti anak-anak seumurnya. 4 MY TOP 10 DOCTOR - Y THE LITTLE VAMPIRE WAKU-WAKU JAPAN FOX FAMILY MOVIES Serial “Doctor-Y” Film ini berkisah bercerita tentang tentang Tony, seorang ahli seorang anak bedah bernama berumur 10 tahun Hideki Kaji yang yang mempunyai memiliki julukan teman vampir “laparoscope bernama Rudolf. magician” dimana ia Persahabatan bertugas di rumah itu terjalin ketika sakit Honokura Rudolf mengalami di pegunungan. perburuan vampir Namun di rumah dan bersembunyi di tempat Tony menginap. sakit tersebut ia mendapat curiga dari para Kesetiakawanan mereka pun semakin terjalin pekerja disana, dan mendapatkan berbagai ketika Rudolf dan keluarganya mengalami masalah yang terjadi di tempat bekerjanya. -

Pres 07012011145906.Pdf

Magazine Members Contents Page 4 Interview with College Council Founded by: James Owusu-Agyemang Page 5 One flew over the Cuckoo‟s nest Co-editors: Andreas Avraam Giselle Quartin Page 6 AIDS Conference Layout and Design: Vanessa Lim Adam Khan Page 8 Agony Aunt Article writers: Zandy Adjirackor Page 10 Book reviews Maheen Choonara Jem Conlon Tessa Fellows Page 12 Fashion Trends Amy Gastman Natalie Gomez Page 14 K-pop sensation Chantal Gyamfi Clinton Heron Page 16 Arcade Fire Luisa Krampoutsa Alex McGeever Ellen Morrison Page 17 The secret life of bees Eghosa Okoro Vishal Patel Page 18 Game Reviews Stefania Polverino Maya Rosenwasser Paige Waymark Page 20 Games Raymond Tsang Nicole Law Before half term, 10 new members of the college council were elected. We managed to have a quick chat with two 6L students, Raymond Tsang and Zandy Adjirackor about what college council means to them and their future hopes for the college. RAYMOND TSANG What does being part of the College council mean to you? Being a member of the college council is an incredible and great responsibility to uphold. I also think that as a member of the college council, it is not just a role to make a say that will probably be vanquished but to make an actual, positive difference within the college. What role do you play in the Council? I‟m a promotions officer, in which I promote current and forthcoming activities and events Golden Oldies: in college. At the moment, we are working on Fundraising Week to raise money for Ox- “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” fam through selling Oxfam bracelets for the Ivor Leigh School Foundation in Sierra Leone, West Africa.