Pt1dssfrntmtr5.1.09 Copy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Student Magazine

Historical Society 6425 SW 6th Avenue Topeka KS 66615 • 785-272-8681 kshs.org ©2014 ARCHAEOLOGY POPULAR REPORT NUMBER 4 STUDENT MAGAZINE The Archaeology of Wichita Indian Shelter in Kansas Cali Letts Virginia A. Wulfkuhle Robert Hoard a ARCHAEOLOGY POPULAR REPORT NUMBER 4 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Getting Started Mystery of the Bone Tool SECTION ONE Archaeology of the Wichita Grass House What Is Archaeology? What Do Archaeologists Do? Your Turn to Investigate! The Mystery Artifact SECTION TWO Protecting Archaeological Resources Is a Civic Responsibility Protecting Archaeological Resources: What Would You Do? Kansas Citizens Who Protect the Past Poster SECTION THREE Learning from the Archaeological Past: The Straw Bale House and a Market Economy Prairie Shelters of the Past and Today Creating a Business in a Market Economy YOUR FINAL PERFORMANCE Marketing Campaign Historical Society All rights reserved. May not be reproduced without permission. ©2014 INTRODUCTION Getting Started dent Jou u rn St a l In this unit you will understand that: • archaeologists investigate the ways people lived in the past • evidence of the past is worth protecting • ideas from the past can solve problems today In addition to this magazine, In this unit you will answer: your teacher will give you a • how do archaeologists investigate the past? Student Journal. This symbol • why is protecting archaeological resources important? • how can ideas from the Wichita Indian shelter solve in the magazine will probems today? signal when to work in your journal. The journal is yours to keep . and the learning is Student Journal yours to keep too. Page 1 – “What Do I Know? What Do I Want to Know?” Complete Columns A and B of the chart. -

![The Story of the Taovaya [Wichita]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0725/the-story-of-the-taovaya-wichita-20725.webp)

The Story of the Taovaya [Wichita]

THE STORY OF THE TAOVAYA [WICHITA] Home Page (Images Sources): • “Coahuiltecans;” painting from The University of Texas at Austin, College of Liberal Arts; www.texasbeyondhistory.net/st-plains/peoples/coahuiltecans.html • “Wichita Lodge, Thatched with Prairie Grass;” oil painting on canvas by George Catlin, 1834-1835; Smithsonian American Art Museum; 1985.66.492. • “Buffalo Hunt on the Southwestern Plains;” oil painting by John Mix Stanley, 1845; Smithsonian American Art Museum; 1985.66.248,932. • “Peeling Pumpkins;” Photogravure by Edward S. Curtis; 1927; The North American Indian (1907-1930); v. 19; The University Press, Cambridge, Mass; 1930; facing page 50. 1-7: Before the Taovaya (Image Sources): • “Coahuiltecans;” painting from The University of Texas at Austin, College of Liberal Arts; www.texasbeyondhistory.net/st-plains/peoples/coahuiltecans.html • “Central Texas Chronology;” Gault School of Archaeology website: www.gaultschool.org/history/peopling-americas-timeline. Retrieved January 16, 2018. • Terminology Charts from Lithics-Net website: www.lithicsnet.com/lithinfo.html. Retrieved January 17, 2018. • “Hunting the Woolly Mammoth;” Wikipedia.org: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Hunting_Woolly_Mammoth.jpg. Retrieved January 16, 2018. • “Atlatl;” Encyclopedia Britannica; Native Languages of the Americase website: www.native-languages.org/weapons.htm. Retrieved January 19, 2018. • “A mano and metate in use;” Texas Beyond History website: https://www.texasbeyondhistory.net/kids/dinner/kitchen.html. Retrieved January 18, 2018. • “Rock Art in Seminole Canyon State Park & Historic Site;” Texas Parks & Wildlife website: https://tpwd.texas.gov/state-parks/seminole-canyon. Retrieved January 16, 2018. • “Buffalo Herd;” photograph in the Tales ‘N’ Trails Museum photo; Joe Benton Collection. A1-A6: History of the Taovaya (Image Sources): • “Wichita Village on Rush Creek;” Lithograph by James Ackerman; 1854. -

Thesis-1973D-A431h.Pdf (8.798Mb)

HEALTH AND MEDICAL CARE OF THE SOUTHERN PLAINS INDIANS, 1868-1892 By VIRGINIA RUTH ALLEN ll Bachelor of Science Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 1952 Master of Teaching Central State University Edmond, Oklahoma 1968 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY July, 1973 OKLAHOMA STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY FEB I;; 1974 HEALTH AND MEDICAL CARE OF THE SOUTHERN PLAINS INDIANS, 1868-1892 Thesis Approved: Dea/] ~ ~Iege 87321~ ii PREFACE During the years from 1868 to 1892, the Southern Plains Indians were defeated in war, their population decreased by battle and disease, and their economic system destroyed. They were relocated on reservations where they were subjected to cultural shock by their white conquerors. They endured hunger, disease, and despair. Many studies have been made of the warfare and the ultimate defeat of the Indians. None have explored the vital topic of the health of these people. No other factor is so vital to the success or failure of human endeavor. This study focuses on the government medical care provided the Plains Indians on the Cheyenne-Arapahoe and Kiowa Comanche reservations. It also expl6res the cultural con flict between the white man's medicine and the native medicine men, and what effect that conflict and other contacts with white men had on Indian health. I wish to acknowledge the generous and kind assis tance I received from numerous people during the research and writing of this dissertation. First, I would like to thank Doctor Homer L. -

Strangers in a Strange Land: a Historical Perspective of the Columbian Quincentenary

Journal of Civil Rights and Economic Development Volume 7 Issue 2 Volume 7, Spring 1993, Issue 2 Article 4 Strangers in a Strange Land: A Historical Perspective of the Columbian Quincentenary Rennard Strickland Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/jcred This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Civil Rights and Economic Development by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STRANGERS IN A STRANGE LAND: A HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE OF THE COLUMBIAN QUINCENTENARY* RENNARD STRICKLAND** The title Strangers in a Strange Land comes from a letter which John Rollin Ridge, the first Native American to practice law in California, wrote from the gold fields back to his Uncle Stand Wa- tie in the Indian Territory. "I was a stranger in a strange land," he began. "I knew no one, and looking at the multitude that thronged the streets, and passed each other without a friendly sign, or look of recognition even, I began to think I was in a new world, where all were strangers and none cared to know."' The last five hundred years-the Columbian Quincentenary-is captured for the Native American in the phrase-"a new world, where all were strangers," with Native Americans as the "stran- gers in a strange land [which] none cared to know." I believe from my historical studies that the so-called "Columbian Ex- change" symbolizes the triumph of technology over axe- ology-the ascendancy of industry over humanity. -

DOCUMENT RESUME RC 021 689 AUTHOR Many Nations

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 424 046 RC 021 689 AUTHOR Frazier, Patrick, Ed. TITLE Many Nations: A Library of Congress Resource Guide for the Study of Indian and Alaska Native Peoples of the United States. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington, DC. ISBN ISBN-0-8444-0904-9 PUB DATE 1996-00-00 NOTE 357p.; Photographs and illustrations may not reproduce adequately. AVAILABLE FROM Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402. PUB TYPE Books (010) Guides Non-Classroom (055) -- Reference Materials Directories/Catalogs (132) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC15 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Alaska Natives; American Indian Culture; *American Indian History; American Indian Languages; *American Indian Studies; *American Indians; Annotated Bibliographies; Federal Indian Relationship; *Library Collections; *Resource Materials; Tribes; United States History IDENTIFIERS *Library of Congress ABSTRACT The Library of Congress has a wealth of information on North American Indian people but does not have a separate collection or section devoted to them. The nature of the Librarv's broad subject divisions, variety of formats, and methods of acquisition have dispersed relevant material among a number of divisions. This guide aims to help the researcher to encounter Indian people through the Library's collections and to enhance the Library staff's own ability to assist with that encounter. The guide is arranged by collections or divisions within the Library and focuses on American Indian and Alaska Native peoples within the United States. Each -

*Certain Exceptions Apply ® MARCH 2016 Muse Volume 20, Issue 03 VP of EDITORIAL & CONTENT Catherine “Lark” Connors DIRECTOR of EDITORIAL James M

® muMARCH 2016 se NO FOOLING* *certain exceptions apply ® MARCH 2016 muse Volume 20, Issue 03 VP OF EDITORIAL & CONTENT Catherine “Lark” Connors DIRECTOR OF EDITORIAL James M. “Scheme” O’Connor FEATURES EDITOR Johanna “Tomfoolery” Arnone CONTRIBUTING EDITOR Meg “Mischief” Moss CONTRIBUTING EDITOR Kathryn “High Jinks” Hulick ASSISTANT EDITOR Jestine “Jest” Ware ART DIRECTOR Nicole “Prank” Welch DESIGNER Jacqui “Joke” Ronan Whitehouse DIGITAL DESIGNER Kevin “Trick” Cuasay RIGHTS & PERMISSIONS David “Spoof” Stockdale BOARD OF ADVISORS ONTARIO INSTITUTE FOR STUDIES IN EDUCATION, UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO Carl Bereiter ORIENTAL INSTITUTE, UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO John A. Brinkman NATIONAL CREATIVITY NETWORK Dennis W. Cheek COOPERATIVE CHILDREN’S BOOK CENTER, A LIBRARY OF THE SCHOOL OF EDUCATION, UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN–MADISON K. T. Horning FREUDENTHAL INSTITUTE Jan de Lange FERMILAB Leon Lederman UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE Sheilagh C. Ogilvie WILLIAMS COLLEGE Jay M. Pasachoff UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO Paul Sereno 10 (Don’t) Fly Me to the Moon Calling all conspiracy theorists by Lela Nargi 16 20 26 40 Not ActuAl Size Rooked! WhAt Killed the WhAt’S So FuNNy? The many faces of caricature The true story diNoSAurS? How we learn to laugh by Kristina Lyn Heitkamp behind a fake robot A theory on trial by Kathiann M. Kowalski by Nick D’Alto by Jeanne Miller CONTENTS VP OF EDITORIAL & CONTENT Catherine “Lark” Connors DIRECTOR OF EDITORIAL James M. “Scheme” O’Connor EDITOR Johanna “Tomfoolery” Arnone DEPARTMENTSDEPARTMENTS CONTRIBUTING EDITOR Meg “Mischief” Moss CONTRIBUTING EDITOR Kathryn “High Jinks” Hulick ASSISTANT EDITOR Jestine “Jest” Ware 2 Parallel U ART DIRECTOR Nicole “Prank” Welch by Caanan Grall DESIGNER Jacqui “Joke” Ronan Whitehouse DIGITAL DESIGNER Kevin “Trick” Cuasay 6 Muse News RIGHTS & PERMISSIONS David “Spoof” Stockdale by Elizabeth Preston 47 Your Tech BOARD OF ADVISORS by Kathryn Hulick ONTARIO INSTITUTE FOR STUDIES IN EDUCATION, UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO Carl Bereiter 48 Last Slice ORIENTAL INSTITUTE, UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO by Nancy Kangas John A. -

Annual Events

TOLL FREE: 888.5EL.RENO FREE: TOLL SOTWBOATRACES.COM 405-641-6386 WWW.ELRENOTOURISM.COM every age to enjoy. to age every weekend. There will be food trucks and entertainment for for entertainment and trucks food be will There weekend. @ELRENOCVB Bring the family and all of your friends for a fun filled filled fun a for friends your of all and family the Bring few remaining head to head flag drop race competitions. competitions. race drop flag head to head remaining few check out our website and follow us on Facebook! on us follow and website our out check Boats from across the United States compete in one of the the of one in compete States United the across from Boats every week. For a current list of things to do be sure to to sure be do to things of list current a For week. every LAKE EL RENO EL LAKE DRAG BOAT RACES BOAT DRAG Something new is added to our calendar of events events of calendar our to added is new Something there’s more! there’s SMOKE ON THE WATER WATER THE ON SMOKE BUT WAIT... BUT July ELRENOCRUISERS.COM 405-350-3048 first full weekend of June. June. of weekend full first USCAVALRY.ORG Cruisers. A Small Town Weekend is held annually on the the on annually held is Weekend Town Small A Cruisers. 405-422-6330 and the Major Howze team mobility event. mobility team Howze Major the and much more! For more information, contact the El Reno Reno El the contact information, more For more! much jumping, platoon drill, bugle competition, authenticity, authenticity, competition, bugle drill, platoon jumping, vendors, food, the only legal burnout in the state and so so and state the in burnout legal only the food, vendors, mounted pistol, military horsemanship and military field field military and horsemanship military pistol, mounted drag races, car show, Classic Car Cruise, live music, music, live Cruise, Car Classic show, car races, drag spirit alive. -

The Place Where Cultures Meet

THE PLACE WHERE TOUR CULTURES MEET PACKAGES WHERE ON THE A DAY OF CULTURES MEET WATER PLAY Experience the culture Soak in the beautiful Try our Traditional of the Haudenosaunee scenery of the Carolinian Haudenosaunee games people as you travel forests as you paddle after exploring the Six the Six Nations of down the Grand River by Nations Tourism displays. the Grand River. canoe or kayak. Then venture out to the Nature Trail, home to the Move through time as you While on this three-hour tour largest area of Carolinian explore rich, pre-contact listen to the Creation Story forest in Canada. history at Kanata Village and the rich history of the Six and Her Majesty’s Royal Nations people. The guided Enjoy a guided tour of Chapel of the Mohawks. tour will take you through rare Chiefswood National Historic Visit the Woodland Cultural ecosystems along the Grand Site and learn the history of Centre, take a guided tour of River as you learn about the the Haudenosaunee medicine Chiefswood National Historic importance of all living things game, Lacrosse. Test your site and Kayanase’s 17th within the Haudenosaunee skills in a scrimmage game century replica longhouse. culture. of lacrosse and archery. In Explore the Six Nations the summer months indulge community by bus to discover in canoeing/kayaking on the where we reside today. Grand River. Tel: 519.758.5444 Toll free: 1.866.393.3001 @sntourism 2498 Chiefswood Road @sixnations.tourism Ohsweken, ON N0A 1M0 @sixnationstourism sixnationstourism.ca Come celebrate our unique heritage and culture Did you know? Surround your senses with l We call ourselves “Haudenosaunee” or ‘the people of the longhouse’, the beat of the drums at our which refers to the large, long houses we once livedTemiscaming in with our Valley East Rayside-Balfour annual Grand River Champion extended families. -

Morrow Final Dissertation 20190801

“THAT’S WHY WE ALWAYS FIGHT BACK”: STRUCTURAL VIOLENCE AND WOMEN’S RESPONSES ON A NATIVE AMERICAN RESERVATION BY REBECCA L. MORROW DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy in Sociology in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2019 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Assata Zerai, Chair Associate Professor Anna-Maria Marshall Associate Professor Ruby Mendenhall Professor Norman Denzin Professor Robert M. Warrior, University of Kansas ABSTRACT This project explores how women who live on a southern California reservation of the Kumeyaay Nation experience and respond to violence. Using a structural violence lens (Galtung 1969) enables a wider view of the definition of violence to include anything that limits an individual’s capabilities. Because the project used an inductive research method, the focus widened a study of intimate partner and family violence to the restrictions caused by the reservation itself, the dispute over membership and inclusion, and health issues that cause a decrease in life expectancy. From 2012 to 2018, I visited the reservation to participate in activities and interviewed 19 residents. Through my interactions, I found that women deploy resiliency strategies in support of the traditional meaning of Ipai/Tipai. This Kumeyaay word translates to “the people” to indicate that those who are participating are part of the community. By privileging the participants’ understanding of belonging, I found three levels of strategies, which I named inter-resiliency (within oneself), intra-resiliency (within the family or reservation) and inter-resiliency (within the large community of Kumeyaay or Native Americans across the country), but all levels exist within the strength gained from being part of the Ipai/Tipai. -

The Pain Experience of Traditional Crow Indian by Norma Kay

The pain experience of traditional Crow Indian by Norma Kay Krumwiede A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Nursing Montana State University © Copyright by Norma Kay Krumwiede (1996) Abstract: The purpose of this qualitative research study was to explore the pain experience of the traditional Crow Indian people. An understanding of the Crow people's experience of pain is crucial in order to provide quality nursing care to members of this population. As nurse researchers gain understanding of these cultural gaps and report their findings, clinically based nurses will be better equipped to serve and meet the unique needs of the traditional Crow Indian. Ethnographic interviews were conducted with 15 traditional Crow Indians currently living on the reservation in southeastern Montana. The informants identified themselves as traditional utilizing Milligan's (1981) typology. Collection of data occurred through (a) spontaneous interviews, (b) observations, (c) written stories, (d) historical landmarks, and (e) field notes. Spradley's (1979) taxonomic analysis method was used to condense the large amount of data into a taxonomy of concepts. The taxonomy of Crow pain evolved into two indigenous categories of “Good Hurt” and “Bad Hurt”. The Crow view “good hurt” as being embedded in natural life events and ceremonies, rituals and healing. The Crow experience "bad hurt” as emanating from two sources: loss and hardship. The Crow believe that every person will experience both “good hurt” and “bad hurt” sometime during their lifetime. The Crow gain knowledge, wisdom and status as they experience, live through, and learn from painful events throughout their lifetime. -

The Emergence and Decline of the Delaware Indian Nation in Western Pennsylvania and the Ohio Country, 1730--1795

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The Research Repository @ WVU (West Virginia University) Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2005 The emergence and decline of the Delaware Indian nation in western Pennsylvania and the Ohio country, 1730--1795 Richard S. Grimes West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Grimes, Richard S., "The emergence and decline of the Delaware Indian nation in western Pennsylvania and the Ohio country, 1730--1795" (2005). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 4150. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/4150 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Emergence and Decline of the Delaware Indian Nation in Western Pennsylvania and the Ohio Country, 1730-1795 Richard S. Grimes Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Mary Lou Lustig, Ph.D., Chair Kenneth A. -

California Folklore Miscellany Index

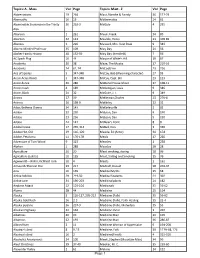

Topics: A - Mass Vol Page Topics: Mast - Z Vol Page Abbreviations 19 264 Mast, Blanche & Family 36 127-29 Abernathy 16 13 Mathematics 24 62 Abominable Snowman in the Trinity 26 262-3 Mattole 4 295 Alps Abortion 1 261 Mauk, Frank 34 89 Abortion 22 143 Mauldin, Henry 23 378-89 Abscess 1 226 Maxwell, Mrs. Vest Peak 9 343 Absent-Minded Professor 35 109 May Day 21 56 Absher Family History 38 152-59 May Day (Kentfield) 7 56 AC Spark Plug 16 44 Mayor of White's Hill 10 67 Accidents 20 38 Maze, The Mystic 17 210-16 Accidents 24 61, 74 McCool,Finn 23 256 Ace of Spades 5 347-348 McCoy, Bob (Wyoming character) 27 93 Acorn Acres Ranch 5 347-348 McCoy, Capt. Bill 23 123 Acorn dance 36 286 McDonal House Ghost 37 108-11 Acorn mush 4 189 McGettigan, Louis 9 346 Acorn, Black 24 32 McGuire, J. I. 9 349 Acorns 17 39 McKiernan,Charles 23 276-8 Actress 20 198-9 McKinley 22 32 Adair, Bethena Owens 34 143 McKinleyville 2 82 Adobe 22 230 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 23 236 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 24 147 McNear's Point 8 8 Adobe house 17 265, 314 McNeil, Dan 3 336 Adobe Hut, Old 19 116, 120 Meade, Ed (Actor) 34 154 Adobe, Petaluma 11 176-178 Meals 17 266 Adventure of Tom Wood 9 323 Measles 1 238 Afghan 1 288 Measles 20 28 Agriculture 20 20 Meat smoking, storing 28 96 Agriculture (Loleta) 10 135 Meat, Salting and Smoking 15 76 Agwiworld---WWII, Richfield Tank 38 4 Meats 1 161 Aimee McPherson Poe 29 217 Medcalf, Donald 28 203-07 Ainu 16 139 Medical Myths 15 68 Airline folklore 29 219-50 Medical Students 21 302 Airline Lore 34 190-203 Medicinal plants 24 182 Airplane