Tae Kwon Do Pumsae Practice and Non-Western Embodied Topoi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Korea Section 3

DEFENSE WHITE PAPER Message from the Minister of National Defense The year 2010 marked the 60th anniversary of the outbreak of the Korean War. Since the end of the war, the Republic of Korea has made such great strides and its economy now ranks among the 10-plus largest economies in the world. Out of the ashes of the war, it has risen from an aid recipient to a donor nation. Korea’s economic miracle rests on the strength and commitment of the ROK military. However, the threat of war and persistent security concerns remain undiminished on the Korean Peninsula. North Korea is threatening peace with its recent surprise attack against the ROK Ship CheonanDQGLWV¿ULQJRIDUWLOOHU\DW<HRQS\HRQJ Island. The series of illegitimate armed provocations by the North have left a fragile peace on the Korean Peninsula. Transnational and non-military threats coupled with potential conflicts among Northeast Asian countries add another element that further jeopardizes the Korean Peninsula’s security. To handle security threats, the ROK military has instituted its Defense Vision to foster an ‘Advanced Elite Military,’ which will realize the said Vision. As part of the efforts, the ROK military complemented the Defense Reform Basic Plan and has UHYDPSHGLWVZHDSRQSURFXUHPHQWDQGDFTXLVLWLRQV\VWHP,QDGGLWLRQLWKDVUHYDPSHGWKHHGXFDWLRQDOV\VWHPIRURI¿FHUVZKLOH strengthening the current training system by extending the basic training period and by taking other measures. The military has also endeavored to invigorate the defense industry as an exporter so the defense economy may develop as a new growth engine for the entire Korean economy. To reduce any possible inconveniences that Koreans may experience, the military has reformed its defense rules and regulations to ease the standards necessary to designate a Military Installation Protection Zone. -

Kup-Pensum 10

KUP-PENSUM 10. KUP - 1. KUP Udarbejdet af Henrik Frost 7. Dan i samarbejde med Sabeumgruppen i ØTK (2017) Kan ændres uden forudgående varsel. Østerbro Taekwondo Klub INDHOLDSFORTEGNELSE: REGLER FOR GRADUERING ............................................................................................................................................ 4 FORORD .................................................................................................................................................................................. 5 Brugen af dette pensum .............................................................................................................. 5 Hvordan skal man tilegne sig Taekwondo? ................................................................................. 7 Disciplin i dojangen ...................................................................................................................... 7 Værdigrundlaget for Østerbro Taekwondo Klub .......................................................................... 8 10. KUP ................................................................................................................................................................................... 11 9. KUP ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 13 8. KUP .................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Safekids USA/Blue Dragon Taekwondo School Belt Requirements

Safe Kids USA LLC Blue Dragon Taekwondo Student Handbook The purpose of the following literature is to assist our students to reach their fitness and training goals while practicing the sport & art of Taekwondo. At the same time, will contribute to establish and develop life forming skills that would reflect the character of a true Taekwondo practitioner. This publication is intended for the use of students and instructors of the Blue Dragon Taekwondo School, and its purpose is to help as a written guide and quick reference during their martial arts training. This manual is not intended for sale, and it will be provided to our students as part of their enrollment materials. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, copied or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the writing permission of the Kids Safe USA LLC/Blue Dragon Taekwondo Control Board. Table of Contents Dedication....................................................................................................................................................4 Introduction..................................................................................................................................................5 A Brief Description and History of Taekwondo......................................................................................6 5 Major Aspects or Componentes of Taekwondo .............................................................................8 Jidokwan -

DEPUTY 1 to DEPUTY 2 Belt

Adult Testing Form DEPUTY 1 to DEPUTY 2 belt Yong In USA Location: ___________________________ □ Taekwondo □ Hapkido Name: ___________________________ Belt Size: ________ I recognize that belts and certificates are awarded only when specific standards of performance are met. In the event that I do not perform to the satisfaction of the testing official(s), promotion may be delayed until further progress has been demonstrated. If I do not achieve the desired degree, I may retest for that degree on the next promotion test date. I recognize that promotion standards are uniform and that each belt degree reflects a specific level of competence. Student Signature: _____________________________________ Date: ________ For Office Use Only Techniques Attitude Aspects Forms Respect: □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 Attitude: □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 1=Excellent 2=Good 3=Needs Work Discipline: □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 Kicking Combination Cooperation: □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 1: □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 Confidence: □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 2: □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 Control: □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 Hapkido White-Purple 1=Excellent 2=Good 3=Needs Work □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 1=Excellent 2=Good 3=Needs Work One Step Sparring (Self-Defense) Philosophy 1: □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 2: □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 Taegeuk Il Jang Taegeuk Oh Jang 3: □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 Taegeuk Ee Jang Taegeuk Yuk Jang 1=Excellent 2=Good 3=Needs Work Taegeuk Sam Jang Taegeuk Chil Jang Board Breaking Taegeuk Sa Jang Taegeuk Pal Jang □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 1=Excellent 2=Good 3=Needs Work Physical Aspects Terminology Basic: □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 Weapons: Flexibility: □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 Nunchaku: “SHANG-JUL-BONG” Free Sparring: □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 Bo Staff: -

![Uta Student Handbook]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9771/uta-student-handbook-509771.webp)

Uta Student Handbook]

2015 UTA – Shins Academy TW Shin Revision: Alex Tse [UTA STUDENT HANDBOOK] Table of Contents What is Taekwondo ........................................................................................................................ 2 The tenets of Taekwondo ............................................................................................................... 2 Internation Taekwondo oath .......................................................................................................... 2 Taekwondo Etiquette ...................................................................................................................... 3 Conduct in the Dojang .................................................................................................................... 3 Ranking System ............................................................................................................................... 3 Patterns(Poomsae) ......................................................................................................................... 4 The Meaning of Taegeuk ................................................................................................................. 5 Taegeuk Poomsae ........................................................................................................................... 5 Sparring (Gyorugi) ........................................................................................................................... 5 Competition Taekwondo................................................................................................................ -

South Korea: Defense White Paper 2010

DEFENSE WHITE PAPER Message from the Minister of National Defense The year 2010 marked the 60th anniversary of the outbreak of the Korean War. Since the end of the war, the Republic of Korea has made such great strides and its economy now ranks among the 10-plus largest economies in the world. Out of the ashes of the war, it has risen from an aid recipient to a donor nation. Korea’s economic miracle rests on the strength and commitment of the ROK military. However, the threat of war and persistent security concerns remain undiminished on the Korean Peninsula. North Korea is threatening peace with its recent surprise attack against the ROK Ship CheonanDQGLWV¿ULQJRIDUWLOOHU\DW<HRQS\HRQJ Island. The series of illegitimate armed provocations by the North have left a fragile peace on the Korean Peninsula. Transnational and non-military threats coupled with potential conflicts among Northeast Asian countries add another element that further jeopardizes the Korean Peninsula’s security. To handle security threats, the ROK military has instituted its Defense Vision to foster an ‘Advanced Elite Military,’ which will realize the said Vision. As part of the efforts, the ROK military complemented the Defense Reform Basic Plan and has UHYDPSHGLWVZHDSRQSURFXUHPHQWDQGDFTXLVLWLRQV\VWHP,QDGGLWLRQLWKDVUHYDPSHGWKHHGXFDWLRQDOV\VWHPIRURI¿FHUVZKLOH strengthening the current training system by extending the basic training period and by taking other measures. The military has also endeavored to invigorate the defense industry as an exporter so the defense economy may develop as a new growth engine for the entire Korean economy. To reduce any possible inconveniences that Koreans may experience, the military has reformed its defense rules and regulations to ease the standards necessary to designate a Military Installation Protection Zone. -

Srovnání Symboliky Taekwon-Do ITF S Taekwondo WTF

UNIVERZITA KARLOVA V PRAZE FILOZOFICKÁ FAKULTA Ústav Dálného východu BAKALÁŘSKÁ PRÁCE SYMBOLIKA V KOREJSKÉM BOJOVÉM UM ĚNÍ TAEKWONDO Hana Seménková PRAHA 2015 Vedoucí bakalá řské práce: PhDr. Mgr. Tomáš Horák, Ph.D. Prohlášení: Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto bakalá řskou práci vypracovala samostatn ě a výhradn ě s použitím citovaných pramen ů, literatury a dalších odborných zdroj ů. Práce nebyla p ředložena jako spln ění studijní povinnosti v rámci jiného studia nebo předložena k obhajob ě v rámci jiného vysokoškolského studia či k získání jiného nebo stejného titulu. V Praze, dne 10. srpna 2015 ............................................. podpis Pod ěkování: Ráda bych pod ěkovala vedoucímu mé bakalá řské práce PhDr. Mgr. Tomáši Horákovi, Ph.D. za pomoc, ochotu a trp ělivost a vedoucí bakalá řského seminá ře Doc. PhDr. Miriam Löwensteinové, Ph.D. za pomoc. Za pomoc p ři hledání odpov ědí bych ráda pod ěkovala Georgeovi Vitalemu, 8.dan. Za velké množství dopl ňujících informací pro tuto práci a vedení k „to, “ chci pod ěkovat Martinu Záme čníkovi, 6. dan. Za vyjasn ění n ěkolika nejasností dále d ěkuji Adrian ě Šimánkové, 3. dan. Abstrakt Předm ětem bakalá řské práce Symbolika v korejském bojovém um ění Taekwondo je analýza symboliky objevující se ve dvou nejv ětších federacích taekwondo – ITF a WTF. První část se stru čně v ěnuje definici termínu symbol, historickému pozadí, vzniku taekwondo a jednotlivých federací a životu Čchö Hong-hŭiho – jedné z nejd ůležit ějších osobností spojených s tímto bojovým um ěním. Druhá, obsáhlejší část, blíže p ředstavuje symboliku, jazykové a vizuální znaky a jejich vývoj u nejrozší řen ějších sm ěrů ITF a WTF. -

978-1-63135-583-7Sample.Pdf

Taekwondo Poomsae: The Fighting Scrolls Guiding Philosophy and Basic Applications By Kingsley Umoh Copyright © 2014 All rights reserved—Kingsley Umoh No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or by any information storage retrieval system, without the permission, in writing, from the publisher. Strategic Book Publishing and Rights Co. 12620 FM 1960, Suite A4-507 Houston, TX 77065 www.sbpra.com ISBN: 978-1-63135-583-7 Book Design: Suzanne Kelly Dedication This book is dedicated to my parents, Akpan Johnny Umoh and Ekaette Akpan Umoh for their stead- fast love and belief in me, to my wife Patricia and children Enobong and Sunil for being able to draw smiles from me even in my moments of frustration, and to the millions of others in the Taekwondo family who find the energy regularly to go through yet another day’s hard physical training. About the Author ingsley Ubong Umoh was only fourteen when he took his first step from Kbeing an ardent fan of the Hong Kong Kung Fu movies into the practical world of Taekwondo Jidokwan training in the early 1980s.As most inveterate martial artists would discover, the exciting world of flying kicks and somer- saults was very different from the hardships of intense training so difficult that it would sometimes appear that the master was actively trying to discourage his students from continuing further classes. Thus was taught the first lesson of perseverance and indomitable spirit. He counts himself fortunate to have trained variously with different instruc- tors to achieve different perspectives which are important to round out one’s knowledge of Taekwondo. -

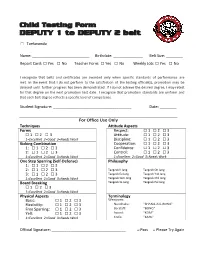

Child Testing Form DEPUTY 1 to DEPUTY 2 Belt

Child Testing Form DEPUTY 1 to DEPUTY 2 belt □ Taekwondo Name: ___________________________ Birthdate: ______________ Belt Size: ________ Report Card: □ Yes □ No Teacher Form: □ Yes □ No Weekly Job: □ Yes □ No I recognize that belts and certificates are awarded only when specific standards of performance are met. In the event that I do not perform to the satisfaction of the testing official(s), promotion may be delayed until further progress has been demonstrated. If I do not achieve the desired degree, I may retest for that degree on the next promotion test date. I recognize that promotion standards are uniform and that each belt degree reflects a specific level of competence. Student Signature: _____________________________________ Date: ________ For Office Use Only Techniques Attitude Aspects Forms Respect: □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 Attitude: □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 1=Excellent 2=Good 3=Needs Work Discipline: □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 Kicking Combination Cooperation: □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 1: □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 Confidence: □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 2: □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 Control: □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 1=Excellent 2=Good 3=Needs Work 1=Excellent 2=Good 3=Needs Work One Step Sparring (Self-Defense) Philosophy 1: □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 2: □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 Taegeuk Il Jang Taegeuk Oh Jang 3: □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 Taegeuk Ee Jang Taegeuk Yuk Jang 1=Excellent 2=Good 3=Needs Work Taegeuk Sam Jang Taegeuk Chil Jang Board Breaking Taegeuk Sa Jang Taegeuk Pal Jang □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 1=Excellent 2=Good 3=Needs Work Physical Aspects Terminology Basic: □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 Weapons: Flexibility: □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 Nunchaku: “SHANG-JUL-BONG” Free Sparring: □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 Bo Staff: “BONG” Yell: □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 Sword: “KOM” 1=Excellent 2=Good 3=Needs Work Knife: “KAHL” Official Signature: ___________________________________ □ Pass □ Please Try Again This form is to be filled out by a parent only. -

Basic Taekwondo Poomsae Taegeuk 1-8

BASIC TAEKWONDO POOMSAE TAEGEUK 1-8 Meaning of the symbol Taegeuk Taegeuk is a symbol representing the principles of the cosmos creation and the norms of human life. The circumference of the Taegeuk mark symbolizes infinity and the two parts, red and blue, inside the circle symbolize yin (negative) and yang (positive), which look like rotating all the time. Therefore, Taegeuk is the light which is the unified core of the cosmos and human life and its boundlessness signifies energy and the source of life. The yin and yang represents the development of the cosmos and human life and the oneness of symmetrical halves, such as negative and positive, hardness and softness, and materials and anti-materials. The eight bar-signs (called kwae) outside the circle are so arranged to go along with the Taegeuk in an orderly system. One bar means the yang and two bars the yin, both representing the creation of harmonization with the basic principles of all cosmos phenomena. The Taegeuk, infinity and yin-yang are the three elements constituting the philosophical trinity as mentioned in the Samil Sinko, the Scripture of Korean race. The Origin of Taegeuk Denomination According to the old book of history, Sinsi Bonki, around (B.C.35), a son of the 5th emperor of the Hwan-ung Dynasty in on ancient nation of the Tongyi race whose name was Pokhui, was said to have received the Heaven's ordinance to have an insight in the universal truths, thereby observing rituals for the Heaven and finally receiving the eight kwaes (bar signs). -

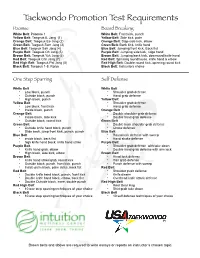

TKD Test Requirements.Pages

Ta e k w o n d o Promotion Test Requirements Poomse Board Breaking White Belt: Poomse 1 White Belt: Front kick, punch Yellow Belt: Taegeuk IL Jang (1) Yellow Belt: Side kick, palm Orange Belt: Taegeuk Ee Jang (2) Orange Belt: Step-side kick, elbow Green Belt: Taegeuk Sam Jang (3) Green Belt: Back kick, knife hand Blue Belt: Taegeuk Sah Jang (4) Blue Belt: Jumping front kick, Back fist Purple Belt: Taegeuk Oh Jang (5) Purple Belt: Jumping side kick, ridge hand Brown Belt: Taegeuk Yuk Jang (6) Brown Belt: Jumping back kick, downward knife hand Red Belt: Taegeuk Chil Jang (7) Red Belt: Spinning roundhouse, knife hand & elbow Red High Belt: Taegeuk Pal Jang (8) Red High Belt: Double round kick, spinning round kick Black Belt: Taegeuk 1-8, Koryo Black Belt: Instructors choice One Step Sparring Self Defense White Belt White Belt • Low block, punch • Shoulder grab defense • Outside block, punch • Hand grab defense • High block, punch Yellow Belt Yellow Belt • Shoulder grab defense • Low block, front kick • Hand grab defense • Inside block, punch Orange Belt Orange Belt • Double shoulder grab defense • Inside block, side kick • Double hand grab defense • Outside block, round kick Green Belt Green Belt • Double back shoulder grab defense • Outside knife hand block, punch • Choke defense • Slide back, jump front kick, punch, punch Blue Belt Blue Belt • Round kick defense with sweep • inside block, back fist • Hand shake defense • high knife hand block, knife hand strike Purple Belt Purple Belt • Shoulder grab defense with take down • Knife hand -

Traditional Taekwondo Union

Traditional Taekwondo Union TRENINGSMÅL, GRADERINGSPENSUM Traditional Taekwondo Union Treningsmål og pensum for TTU-klubber Kwanjang Nim Cho Woon Sup 9. Dan Utgave: 24. mai 2009 Coppyright Traditional Taekwondo Union Side: 1 Traditional Taekwondo Union Internet: www.ttu.no | President TTU Email: [email protected] | General secretary TTU Email: [email protected] Traditional Taekwondo Union Innhold Innhold .................................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Forord og forklaringer ............................................................................................................................................................................. 4 HVA ER TAEKWONDO .......................................................................................................................................................................... 5 HVORFOR LÆRE TAEKWONDO ............................................................................................................................................................ 5 FORDELER VED TAEKWONDO .............................................................................................................................................................. 5 Beltefarger ............................................................................................................................................................................................... 6