The BIA Branch of Wildland Fire Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gao-13-684, Wildland Fire Management

United States Government Accountability Office Report to Congressional Requesters August 2013 WILDLAND FIRE MANAGEMENT Improvements Needed in Information, Collaboration, and Planning to Enhance Federal Fire Aviation Program Success GAO-13-684 August 2013 WILDLAND FIRE MANAGEMENT Improvements Needed in Information, Collaboration, and Planning to Enhance Federal Fire Aviation Program Success Highlights of GAO-13-684, a report to congressional requesters Why GAO Did This Study What GAO Found The Forest Service and Interior The Department of Agriculture’s Forest Service and the Department of the contract for aircraft to perform various Interior have undertaken nine major efforts since 1995 to identify the number and firefighting functions, including type of firefighting aircraft they need, but those efforts—consisting of major airtankers that drop retardant. The studies and strategy documents—have been hampered by limited information Forest Service contracts for large and collaboration. Specifically, the studies and strategy documents did not airtankers and certain other aircraft, incorporate information on the performance and effectiveness of firefighting while Interior contracts for smaller aircraft, primarily because neither agency collected such data. While government airtankers and water scoopers. reports have long called for the Forest Service and Interior to collect aircraft However, a decrease in the number of performance information, neither agency did so until 2012 when the Forest large airtankers, from 44 in 2002 to 8 in Service began a data collection effort. However, the Forest Service has collected early 2013—due to aging planes and several fatal crashes—has led to limited data on large airtankers and no other aircraft, and Interior has not initiated concerns about the agencies’ ability to a data collection effort. -

Cub Creek 2 Fire Evening Update July 17, 2021 Evening Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest

Cub Creek 2 Fire Evening Update July 17, 2021 Evening Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest Fire Information Line – (541)-670-0812 (8:00 am to 8:00 pm) Winthrop, WA — Cub Creek 2 – Extended attack of the Cub Creek 2 Fire continued today with retardant drops from large air tankers, water scooping/dropping planes, helicopters with buckets and various ground forces of hand crews and engines. The fire burned vigorously throughout the day on Washington Department of Natural Resource and Okanogan County Fire District 6 protected lands and also the Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest. The majority of the left flank of the fire is lined with dozer line from the heel of the fire to First Creek Road which ties into Forest Road 140 leading to Buck Lake. The north flank remains unchecked at this time. The northeast flank is backing down toward West Chewuch Road where it had crossed north of the junction of the East and West Chewuch Road to Heaton Homestead. The fire is also located east of Boulder Creek Road and is burning towards the north being pushed by diurnal winds. Northwest Incident Management Team 8 assumed management of the fire this evening at 6 p.m. Tonight, a night shift of firefighters include a 20-person handcrew, five engines, and multiple overhead. The Washington State structure strike team has been reassigned to protect properties in the Cub Creek 2 Fire. 8 Mile Ranch is the designated staging area. Evacuation Information: The Okanogan County Emergency Management (OCEM) evacuations for the Chewuch River drainage effected by the Cub Creek 2 Fire remain. -

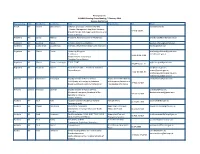

Annex B Participant List of ISG Open Meeting

Participants list INSARAG Steering Group Meeting, 7 February 2019 Geneva, Switzerland Representing Title FirstName LastName Role Organisation Tel Email AnsuR Mr Harald Skinnemoen Software Developer / Provider (ASIGN) [email protected] - Disaster Management App/Web. Solutions 47 928 466 51 Provider for UN. Ref. Jesper Lund (OCHA), Einar Bjorgo (UNOSAT) Argentina Mr. Carlos Alfonso President, National Council of Firefighters [email protected] Argentina Mr. Gustavo Nicola Director, National Firefighters [email protected] Argentina Ms Gisela Anahi Lazarte Rossi Miembro del gerenciamiento USAR Argentina [email protected] Argentina Mr. Martín Torres Operating & Logistic [email protected], Coordinator [email protected] 54 11 48 19 70 00 White Helmets Commission Comision Cascos Blancos Argentina Mr. Martin Gomez Lissarrague FOCAL POINT [email protected] 54 294 452 57 70 Argentina Mr. Alejandro Daneri Punto Focal Político - Presidente COmisión [email protected]; Cascos Blancos [email protected]; 54 11 481 989 38 [email protected]; [email protected] Armenia Colonel Hovhannes Yemishyan Deputy Director of Rescue Service Rescue ServiceThe Ministry [email protected] The Ministry of Emergency Situations of Emergency Situations of 37 410 317 804 INSARAG National Focal Point.UNDAC FP The Republic of Armenia Armenia Colonel Artavazd Davtyan Deputy Director of Rescue Service, [email protected], Ministry of Emergency Situations of the [email protected] 374 12 317 815 Republic of Armenia, -

Fire Service Features of Buildings and Fire Protection Systems

Fire Service Features of Buildings and Fire Protection Systems OSHA 3256-09R 2015 Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 “To assure safe and healthful working conditions for working men and women; by authorizing enforcement of the standards developed under the Act; by assisting and encouraging the States in their efforts to assure safe and healthful working conditions; by providing for research, information, education, and training in the field of occupational safety and health.” This publication provides a general overview of a particular standards- related topic. This publication does not alter or determine compliance responsibilities which are set forth in OSHA standards and the Occupational Safety and Health Act. Moreover, because interpretations and enforcement policy may change over time, for additional guidance on OSHA compliance requirements the reader should consult current administrative interpretations and decisions by the Occupational Safety and Health Review Commission and the courts. Material contained in this publication is in the public domain and may be reproduced, fully or partially, without permission. Source credit is requested but not required. This information will be made available to sensory-impaired individuals upon request. Voice phone: (202) 693-1999; teletypewriter (TTY) number: 1-877-889-5627. This guidance document is not a standard or regulation, and it creates no new legal obligations. It contains recommendations as well as descriptions of mandatory safety and health standards. The recommendations are advisory in nature, informational in content, and are intended to assist employers in providing a safe and healthful workplace. The Occupational Safety and Health Act requires employers to comply with safety and health standards and regulations promulgated by OSHA or by a state with an OSHA-approved state plan. -

Pre's Mom Dies at 88

C M C M Y K Y K TAKING CHARGE New MHS coach hits the ground running, B1 See be SUM low for MER SIZ Your ZLER Choice Event B AY AP PLIAN THE CE & TV MATTR STORE ESS Serving Oregon’s South Coast Since 1878 THURSDAY,JULY 18, 2013 RV Jamboree opens door for more tourism BY TIM NOVOTNY The World NORTH BEND — The Bay Area is starting to reap the rewards of a massive motor coach rally that took place in 2012. Today will conclude the Oregon Coast RV Jamboree, a new event at The Mill Casino-Hotel sponsored by Guaranty RV Super Centers. The event saw dozens of vehicles visiting, and included a Menasha forest tour and traditional tribal salmon bake. Ray Doering, communications manager for the Mill, says the Bay Area can expect more of these rallies in the future coming off the success of last year’s massive Family Motor Coach Association Northwest Rally. File photo by Lou Sennick, The World Elfriede Prefontaine, second from left, the mother of the late Steve Prefontaine died in Eugene on Wednesday at the age of 88. Here, she SEE JAMBOREE | A10 attended the dedication of the Prefontaine Track at Marshfield High School on April 28, 2001. Daughter Linda Prefontaine is on the right in the brown coat. Pre’s mom dies at 88 FROM STAFF AND that Prefontaine had been hospital- the University of Oregon, setting WIRE SERVICE REPORTS ized after suffering a fall at her assist- seven American records in distance ed living facility. track events. COOS BAY — The last surviving Born in Germany, Elfriede met her He competed in the 1972 Olympic husband Raymond in 1946 when he parent of legendary runner Steve Games in Munich before he died in a was an occupying U.S. -

A Preparedness Guide for Firefighters and Their Families

A Preparedness Guide for Firefighters and Their Families JULY 2019 A Preparedness Guide for Firefighters and Their Families July 2019 NOTE: This publication is a draft proof of concept for NWCG member agencies. The information contained is currently under review. All source sites and documents should be considered the authority on the information referenced; consult with the identified sources or with your agency human resources office for more information. Please provide input to the development of this publication through your agency program manager assigned to the NWCG Risk Management Committee (RMC). View the complete roster at https://www.nwcg.gov/committees/risk-management-committee/roster. A Preparedness Guide for Firefighters and Their Families provides honest information, resources, and conversation starters to give you, the firefighter, tools that will be helpful in preparing yourself and your family for realities of a career in wildland firefighting. This guide does not set any standards or mandates; rather, it is intended to provide you with helpful information to bridge the gap between “all is well” and managing the unexpected. This Guide will help firefighters and their families prepare for and respond to a realm of planned and unplanned situations in the world of wildland firefighting. The content, designed to help make informed decisions throughout a firefighting career, will cover: • hazards and risks associated with wildland firefighting; • discussing your wildland firefighter job with family and friends; • resources for peer support, individual counsel, planning, and response to death and serious injury; and • organizations that support wildland firefighters and their families. Preparing yourself and your family for this exciting and, at times, dangerous work can be both challenging and rewarding. -

Landscape Fire Crisis Mitigation

FIRE-IN FIre and REscue Innovation Network Thematic Working Group Vegetation Fires EC 20171127 1 | F IRE-IN has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation programme under grant agreement N°740 575 Main Activities Objective main lines: (i) Identification and harmonisation of operational Improve the National capability gaps and European Fire & (ii) Scouting of Rescue Capability promising Development solutions Process (iii) Definition of a Fire & Rescue Strategic Research and Standardisation Agenda | 2 Conceptual Pillars | 3 5 Thematic Working Groups + involvement of Associated Experts A. Search and Rescue B. Structural fires C. Vegetation fires D. Natural disasters E. CBRNE (SAR) and emergency CNVVF GFMC THW CAFO Medical Response ENSOSP, CAFO, SGSP, CFS, PCF, MSB, KEMEA MSB, CNVVF, CFS, KEMEA ENSOSP, SGSP, CFS, MSB KEMEA, CNVVF SAFE, ENSOSP, CNVVF, FIRE-IN CAFO Associated Experts (AE) community (international community including key thematic practitioner experts from public, private, NGOs bodies, and representative of thematic working groups from existing networks) 1000 experts expected | 4 Thematic Group C – Vegetation / Landscape Fires Partners - Global Fire Monitoring Center (GFMC) (lead) - Catalonian Fire Service - Pau Costa Foundation - Int. Ass. Fire & Rescue Services (CTIF) - KEMEA - European Associated Experts and thematic networks and other stakeholders (community of practitioners) | Thematic Group C – Vegetation / Landscape Fires Emphasis - Science-Policy-Interface - Underlying causes of landscape -

Wildland Fire Incident Management Field Guide

A publication of the National Wildfire Coordinating Group Wildland Fire Incident Management Field Guide PMS 210 April 2013 Wildland Fire Incident Management Field Guide April 2013 PMS 210 Sponsored for NWCG publication by the NWCG Operations and Workforce Development Committee. Comments regarding the content of this product should be directed to the Operations and Workforce Development Committee, contact and other information about this committee is located on the NWCG Web site at http://www.nwcg.gov. Questions and comments may also be emailed to [email protected]. This product is available electronically from the NWCG Web site at http://www.nwcg.gov. Previous editions: this product replaces PMS 410-1, Fireline Handbook, NWCG Handbook 3, March 2004. The National Wildfire Coordinating Group (NWCG) has approved the contents of this product for the guidance of its member agencies and is not responsible for the interpretation or use of this information by anyone else. NWCG’s intent is to specifically identify all copyrighted content used in NWCG products. All other NWCG information is in the public domain. Use of public domain information, including copying, is permitted. Use of NWCG information within another document is permitted, if NWCG information is accurately credited to the NWCG. The NWCG logo may not be used except on NWCG-authorized information. “National Wildfire Coordinating Group,” “NWCG,” and the NWCG logo are trademarks of the National Wildfire Coordinating Group. The use of trade, firm, or corporation names or trademarks in this product is for the information and convenience of the reader and does not constitute an endorsement by the National Wildfire Coordinating Group or its member agencies of any product or service to the exclusion of others that may be suitable. -

2021 Active Business Licenses, 6/7/21

2021 ACTIVE BUSINESS LICENSES, 6/7/21 Business Name Location Location City Description AUCTION COMPANY OF SOUTHERN OR 347 S BROADWAY COOS BAY Auctions 101 COASTAL DETAILING & ATV REPAIR 1889 N BAYSHORE DR COOS BAY Auto/Equipment Repair METRIC MOTORWORKS, INC. 3500 OCEAN BLVD SE COOS BAY Auto/Equipment Repair PRO TOWING 63568 WRECKING ROAD COOS BAY Auto/Equipment Repair 1996 LLC DBA CHAMBERS CONSTRUCTION COMPA 3028 JUDKINS RD STE 1 EUGENE General Contractors 4C'S ENVIRONMENTAL INC 1590 SE UGLOW AVE DALLAS General Contractors 7 MILE CONTRACTING LLC 48501 HWY 242 BROADBENT General Contractors A AND R SOLAR SPC 6800 NE 59TH PL PORTLAND General Contractors ABSOLUTE ROOFING AND MAINTENANCE LLC 92589 DUNES LN NORTH BEND General Contractors AC SCHOMMER & SONS, INC. 6421 NE COLWOOD PORTLAND General Contractors ACACIA II 501 N 10TH ST COOS BAY General Contractors ACTIVE FLOW, LLC 63569 SHINGLEHOUSE RD COOS BAY General Contractors ADAIR HOMES, INC 172 MELTON RD CRESWELL General Contractors AECOM TECHNICAL SERVICES, INC 111 SW COLUMBIA ST STE 1500 PORTLAND General Contractors AJP CONSTRUCTION 1682 APPLEWOOD DR COOS BAY General Contractors ALL AROUND SIGNS 69777 STAGE RD COOS BAY General Contractors ALL COAST HEATING & AIR , LLC 68212 RAVINE NORTH BEND General Contractors ALL NATURAL PEST ELIMINATION 3445 S PACIFIC HWY MEDFORD General Contractors AMERICAN CARPORTS, INC. 457 N BROADWAY ST JOSHUA General Contractors AMERICAN INDUSTRIAL DOOR, LLC 515 N LAKE RD COOS BAY General Contractors AMP CONSTRUCTION LLC 50147 HIGHWAY 101 BANDON General Contractors ANGLE & SQUARE LLC 2067 ROYAL SAINT GEORGE DR FLORENCE General Contractors APOLLO MECHANICAL CONTRACTORS 1207 W COLUMBIA DR KENNEWICK General Contractors APPLIED REFRIGERATION TECH INC 6608 TABLE ROCK RD STE 3 MEDFORD General Contractors ARCADIA ENVIRONMENTAL, INC 3164 OCEAN BLVD S.E. -

Forest Service Job Corps Civilian Conservation Center Wildland Fire

Forest Service Job Corps Civilian Conservation Center Wildland Fire Program 2016 Annual Report Weber Basin Job Corps: Above Average Performance In an Above Average Fire Season Brandon J. Everett, Job Corps Forest Area Fire Management Officer, Uinta-Wasatch–Cache National Forest-Weber Basin Job Corps Civilian Conservation Center The year 2016 was an above average season for the Uinta- Forest Service Wasatch-Cache National Forest. Job Corps Participating in nearly every fire on the forest, the Weber Basin Fire Program Job Corps Civilian Conservation Statistics Center (JCCCC) fire program assisted in finance, fire cache and camp support, structure 1,138 students red- preparation, suppression, moni- carded for firefighting toring and rehabilitation. and camp crews Weber Basin firefighters re- sponded to 63 incidents, spend- Weber Basin Job Corps students, accompanied by Salt Lake Ranger District Module Supervisor David 412 fire assignments ing 338 days on assignment. Inskeep, perform ignition operation on the Bear River RX burn on the Bear River Bird Refuge. October 2016. Photo by Standard Examiner. One hundred and twenty-four $7,515,675.36 salary majority of the season commit- The Weber Basin Job Corps fire camp crews worked 148 days paid to students on ted to the Weber Basin Hand- program continued its partner- on assignment. Altogether, fire crew. This crew is typically orga- ship with Wasatch Helitack, fire assignments qualified students worked a nized as a 20 person Firefighter detailing two students and two total of 63,301 hours on fire Type 2 (FFT2) IA crew staffed staff to that program. Another 3,385 student work assignments during the 2016 with administratively deter- student worked the entire sea- days fire season. -

Wildland Fire Management: Uniform Crew T-Shirts Within Bureau of Land

Wildland Fire Management: Uniform crew t-shirts within Bureau of Land Management Fire and Aviation Management programs By: Jeffrey L. Fedrizzi Oregon-Washington State Office of Fire and Aviation Management U.S. Bureau of Land Management, Portland, Oregon 2 Uniform crew t-shirts within Bureau of Land Management Fire and Aviation Management programs CERTIFICATION STATEMENT I hereby certify that this paper constitutes my own product, that where the language of others is set forth, quotation marks so indicate, and that appropriate credit is given where I have used the language, ideas, expressions, or writings of another. Signed: __________________________________ 3 Uniform crew t-shirts within Bureau of Land Management Fire and Aviation Management programs Abstract Uniforms help create an identity, pride in appearance, and an esprit de corps essential to an effective organization. Wearing a uniform affects individual behavior including self-discipline, integrity, and organizational ownership. This applied research project’s problem statement is Bureau of Land Management (BLM) policy neither provides for nor funds the purchase of fire crew uniform t-shirts. The purpose of this research is to determine whether or not agency-provided uniform fire crew t-shirts are necessary and, if so, what type would be most appropriate to recommend for a policy change within the BLM. The evaluative method of research was used for the following research questions: 1. What is the importance of uniforms within the fire service? 2. What are firefighters’ preferred materials for fire crew uniform t-shirts within the interagency fire service community? 3. What is BLM manual policy for general staff and law enforcement uniforms? 4. -

Occupational Risks and Hazards Associated with Firefighting Laura Walker Montana Tech of the University of Montana

Montana Tech Library Digital Commons @ Montana Tech Graduate Theses & Non-Theses Student Scholarship Summer 2016 Occupational Risks and Hazards Associated with Firefighting Laura Walker Montana Tech of the University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.mtech.edu/grad_rsch Part of the Occupational Health and Industrial Hygiene Commons Recommended Citation Walker, Laura, "Occupational Risks and Hazards Associated with Firefighting" (2016). Graduate Theses & Non-Theses. 90. http://digitalcommons.mtech.edu/grad_rsch/90 This Non-Thesis Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Montana Tech. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses & Non-Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Montana Tech. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Occupational Risks and Hazards Associated with Firefighting by Laura Walker A report submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Industrial Hygiene Distance Learning / Professional Track Montana Tech of the University of Montana 2016 This page intentionally left blank. 1 Abstract Annually about 100 firefighters die in the line duty, in the United States. Firefighters know it is a hazardous occupation. Firefighters know the only way to reduce the number of deaths is to change the way the firefighter (FF) operates. Changing the way a firefighter operates starts by utilizing traditional industrial hygiene tactics, anticipating, recognizing, evaluating and controlling the hazard. Basic information and history of the fire service is necessary to evaluate FF hazards. An electronic survey was distributed to FFs. The first question was, “What are the health and safety risks of a firefighter?” Hypothetically heart attacks and new style construction would rise to the top of the survey data.