Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Erase Me": Gary Numan's 1978-80 Recordings

Ought: The Journal of Autistic Culture Volume 2 Issue 2 Article 4 June 2021 "Erase Me": Gary Numan's 1978-80 Recordings John Bruni [email protected], [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/ought Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Disability Studies Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Bruni, John (2021) ""Erase Me": Gary Numan's 1978-80 Recordings," Ought: The Journal of Autistic Culture: Vol. 2 : Iss. 2 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/ought/vol2/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ought: The Journal of Autistic Culture by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Erase Me”: Gary Numan’s 1978-80 Recordings John Bruni ary Numan, almost any way you look at him, makes for an unlikely rock star. He simply never fits the archetype: his best album, both Gin terms of artistic and commercial success, The Pleasure Principle (1979), has no guitars on it; his career was brief; and he retired at his peak. Therefore, he has received little critical attention; the only book-length analysis of his work is a slim volume from Paul Sutton (2018), who strains to fit him somehow into the rock canon. With few signposts at hand—and his own open refusal to be a star—writing about Numan is admittedly a challenge. In fact, Numan is a good test case for questioning the traditional belief in the authenticity of individual artistic genius. -

Michigan's Copper Country" Lets You Experience the Require the Efforts of Many People with Different Excitement of the Discovery and Development of the Backgrounds

Michigan’s Copper Country Ellis W. Courter Contribution to Michigan Geology 92 01 Table of Contents Preface .................................................................................................................. 2 The Keweenaw Peninsula ........................................................................................... 3 The Primitive Miners ................................................................................................. 6 Europeans Come to the Copper Country ....................................................................... 12 The Legend of the Ontonagon Copper Boulder ............................................................... 18 The Copper Rush .................................................................................................... 22 The Pioneer Mining Companies................................................................................... 33 The Portage Lake District ......................................................................................... 44 Civil War Times ...................................................................................................... 51 The Beginning of the Calumet and Hecla ...................................................................... 59 Along the Way to Maturity......................................................................................... 68 Down the South Range ............................................................................................. 80 West of the Ontonagon............................................................................................ -

Poetry Festival 2021

POETRY FESTIVAL 2021 Dr Mary Jean Chan Adjudicator Photo © Adrian Pope Mary Jean Chan is the author of Flèche, published by Faber & Faber (2019). Flèche won the 2019 Costa Book Award for Poetry and was shortlisted for the International Dylan Thomas Prize, the Seamus Heaney Centre First Collection Poetry Prize and the Jhalak Prize. In Spring 2020, Chan served as guest co-editor with Will Harris at The Poetry Review. Born and raised in Hong Kong, Chan is Senior Lecturer in Creative Writing (Poetry) at Oxford Brookes University and lives in London. Cover artwork by Molly Rowlands 3 YEAR 7 Greece Andrea Herr Path at Dusk Molly Baker Wittering Lila Baroukh Wind Tallis Philpot Midnight Mourning Juno Arnold Who am I? Isabella Watton A Sign Hannah Bong A Key Just Out of Reach Freya Wright I Remember That Day on the Bridge Avani Chotai Change is Necessary Zara Zwain YEAR 8 Birds Learn How to Fly One Day Maya Navon A Stranger Taylor Eldridge Memories of Rome Tallulah Galvani By the Sea – Memories Sofia di Stefano Market Square Poppie Lawrie Younger Then Olivia Moore A Magpie’s Odyssey Leah Katz Do You Remember? Chloe Saunders Marloes Alice Day YEAR 9 Recruitment Sarah Fleming The Price of Love Isobel Parry-Jones Who I Am Ines Kirdar-Smith The Dream Xanthe Picchioni The Other Place Saffi Bowen Home Lucy-Mai Adjetey Night Livia Michaels Hope Sora Kamide Dreams Imogen Whelan Who Said? Charlotte Walker 4 YEAR 10 Anthropocene Delilah Dowd The Business of the Day Imi Bell Manderley Laila Samarasinghe George Stubbs: Whistlejacket Olivia Clement Blue Herons -

Smash Hits Volume 57

H' II i.C'^Wf'«^i^i'>SSH"WS'^~'^'-"' 0!!^ Feb 5-18 1981 Vol.3 No 3 g^g^<nFG^gJJ^ Another issue already? I'd rather watch paint dry. Let's see what drivel they're trying to palm off on us this time. Features on Madness and Phil Collins? 1 mean, honestly, i don't suppose it's even occurred to them to interview The Strang ... oh, they have. But as for the rest of it, who really wants a colour poster of Adam or the chance to win the new Gen X album? What happened to the Sky pin-up they promised us? What about the feature on pencil sharpeners, the win a string bag competition, the paper clip giveaway? No sign of any of it. 1 mean, honestly. I'd write a letter if 1 were you . VIENNA Ultravox 2 ROMEO AND JULIET Dire Straits 8 ROCK THIS TOWN Stray Cats 10 TAKE MY TIME Sheena Easton 13 IN THE AIR TONIGHT Phil Collins 16 ZEROX Adam And The Ants 20 THE BEST OF TIMES Styx 21 GANGSTERS OF THE GROOVE Heatwave 22 MESSAGE OF LOVE Pretenders 26 TURN ME ON TURN ME OFF Honey Bane 26 BORN TO RUN Bruce Springsteen 33 TWILIGHT CAFE Susan Fassbender 36 1.0. U. Jane Kennaway 36 LONELY HEART U.F.O 43 1 SURRENDER Rainbow 43 MADNESS: Feature 4/5/6 PHIL COLLINS: Feature 14/15/16 ADAM AND THE ANTS: Colour Poster 24/25 THE STRANGLERS: Feature 34/35 DEBBIE HARRY: Colour Poster 44 DISC JOCKEYS 9 CARTOON 9 BITZ 11/12 CROSSWORD 18 INDEPENDENT BITZ 19 DISCO 22 REVIEWS 28/29 STAR TEASER 30 SOUNDAROUND/GEN X COMPETITION 31 BIRO BUDDIES 32 COMPETITION WINNERS ...! 37 LEHERS .„..39/40 GIGZ • 42 This magazine is published by EMAP Nationaf Publications Ltd, Peterborough, and is printed by East Midland Utbo Printers, Peterborough. -

ゲイリー・ニューマン別れよう = This Wreckage Mp3, Flac

ゲイリー・ニューマン 別れよう = This Wreckage mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: 別れよう = This Wreckage Country: Japan Released: 1981 Style: Synth-pop MP3 version RAR size: 1448 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1375 mb WMA version RAR size: 1274 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 615 Other Formats: WAV AC3 AA WMA RA ASF VOC Tracklist A This Wreckage = 別れよう 5:22 B Photograph = フォトグラフ 2:23 Companies, etc. Licensed From – Atlantic Recording Corporation Phonographic Copyright (p) – Beggars Banquet Made By – Warner-Pioneer Corporation Credits Producer, Written-By – Gary Numan Notes ℗ 1980 Beggars Banquet Made By Warner Pioneer Corporation, Japan, under license from Atlantic Recording Corp. U.S.A. Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout (A side label): P-1515A1 Matrix / Runout (B side label): P-1515A2 Matrix / Runout (A-Side Runout): P-1515 A-1 1-A-7 Matrix / Runout (B-Side Runout): P-1515 A-2 1-B-5 Rights Society: JASRAC Other (Price): ¥700 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year This Wreckage (7", Beggars BEG 50 Gary Numan BEG 50 UK 1980 Single) Banquet This Wreckage (7", Beggars BEG 50 Gary Numan BEG 50 Ireland 1980 Single) Banquet 100161 Gary Numan This Wreckage (7") WEA 100161 Australia 1980 ゲイリー・ニューマン* = Gary Atlantic, ゲイリー・ニューマン* = Numan - 別れよう = This P-1515A Beggars P-1515A Japan 1981 Gary Numan Wreckage (7", Single, Banquet Promo) This Wreckage (7", Beggars INT 111.607 Gary Numan INT 111.607 Germany 1980 Single) Banquet Related Music albums to 別れよう = This Wreckage by ゲイリー・ニューマ ン Gary Numan = ゲイリー・ニューマン, Dramatis = ドラマティス - 恋のアドヴェンチャー = Love Needs No Disguise ゲイリー・ニューマン = Gary Numan - ガラスのヒーロー = We Are Glass Gary Numan - Living Ornaments '80 Gary Numan - She's Got Claws Tubeway Army / Gary Numan - Are Friends Electric? / I Die You Die Gary Numan - Warriors Gary Numan - Telekon LP Gary Numan - Cars Gary Numan / Tubeway Army - The Premier Hits Gary Numan - Telekon. -

Gary Numan Exhibition Mp3, Flac, Wma

Gary Numan Exhibition mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Rock / Pop Album: Exhibition Country: Canada Released: 1987 Style: Punk, Synth-pop MP3 version RAR size: 1751 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1683 mb WMA version RAR size: 1395 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 666 Other Formats: ADX VQF MMF TTA DTS WMA VOC Tracklist Hide Credits 1-1 Me! I Disconnect From You (Live) That's Too Bad 1-2 Mixed By – Mick Glossop 1-3 My Love Is A Liquid 1-4 Music For Chameleons 1-5 We Are Glass 1-6 Jo The Waiter 1-7 On Broadway 1-8 Are 'Friends' Electric? 1-9 I Dream Of Wires 1-10 Complex 1-11 Noise Noise Love Needs No Disguise 1-12 Producer – Dramatis, Simon Heywood* Bombers 1-13 Producer – Kenny Denton 1-14 Moral 1-15 Warriors 1-16 Everyday I Die (Live) 1-17 This Wreckage 1-18 Cars 2-1 We Take Mystery To Bed 2-2 I'm An Agent 2-3 My Centurion 2-4 Metal 2-5 You Are My Vision 2-6 Sister Surprise 2-7 I Die: You Die 2-8 She's Got Claws Stormtrooper In Drag 2-9 Vocals – Gary Numan 2-10 My Shadow In Vain 2-11 Down In The Park 2-12 Do You Need The Service? 2-13 The Iceman Comes 2-14 No More Lies 2-15 Change Your Mind 2-16 Voices Cars ('E' Reg Remixed Model) 2-17 Remix – Zeus B. Held Notes In thick double CD box; note different tracklisting than the UK version. -

Untitled Emotions Mix with Gentle Fear Between Caramel Colored Hurt Under All This Raw Feeling Here Gathered Along the Crimson Dirt

Mrs. Sturgis’ 3B Creative Writing Class asks you to: Free your mind, You’ll be surprised at what you may find. ANTHEM OF THE ANGELS WE ARE THE BROKEN In our grassy kingdom we lay. I watched the screaming, Sitting in the warm summer rays. The lies, deceit, and the pain it’s bringing. It was magic, it was bliss – I’ve watched us fall from faith. We believed nothing could ruin this. I watched us, our red ribbon of fabricated blood Now we’ll sing the Anthem of the Angels break. As we lay it down to rest. I’ve watched the hideous names run across the room, As all things it ends – I’ve watched babies be born too soon. And so must this, my friend. The rain had come down, I’ve seen you when you were about to break Leaving nothing but it’s torturous burning From the love and heart he seemed to take. sound. I’ve seen him when he was on his knees And then we’ll all come together to sing – Dear Begging for you not to leave. Agony I’ve seen what it means to have a home Let me fall slowly. And these things are all I’ve ever known. The green was gone and I was alone. But you didn't see me behind that door – The nightmarish dream had grown. Wishing our family would be whole once more. Staring, lost in this lack of Technicolor, You didn't see when I lost my fragile mind I wish that we could have suffered together. -

WARNER BROS. / WEA RECORDS 1970 to 1982

AUSTRALIAN RECORD LABELS WARNER BROS. / WEA RECORDS 1970 to 1982 COMPILED BY MICHAEL DE LOOPER © BIG THREE PUBLICATIONS, APRIL 2019 WARNER BROS. / WEA RECORDS, 1970–1982 A BRIEF WARNER BROS. / WEA HISTORY WIKIPEDIA TELLS US THAT... WEA’S ROOTS DATE BACK TO THE FOUNDING OF WARNER BROS. RECORDS IN 1958 AS A DIVISION OF WARNER BROS. PICTURES. IN 1963, WARNER BROS. RECORDS PURCHASED FRANK SINATRA’S REPRISE RECORDS. AFTER WARNER BROS. WAS SOLD TO SEVEN ARTS PRODUCTIONS IN 1967 (FORMING WARNER BROS.-SEVEN ARTS), IT PURCHASED ATLANTIC RECORDS AS WELL AS ITS SUBSIDIARY ATCO RECORDS. IN 1969, THE WARNER BROS.-SEVEN ARTS COMPANY WAS SOLD TO THE KINNEY NATIONAL COMPANY. KINNEY MUSIC INTERNATIONAL (LATER CHANGING ITS NAME TO WARNER COMMUNICATIONS) COMBINED THE OPERATIONS OF ALL OF ITS RECORD LABELS, AND KINNEY CEO STEVE ROSS LED THE GROUP THROUGH ITS MOST SUCCESSFUL PERIOD, UNTIL HIS DEATH IN 1994. IN 1969, ELEKTRA RECORDS BOSS JAC HOLZMAN APPROACHED ATLANTIC'S JERRY WEXLER TO SET UP A JOINT DISTRIBUTION NETWORK FOR WARNER, ELEKTRA, AND ATLANTIC. ATLANTIC RECORDS ALSO AGREED TO ASSIST WARNER BROS. IN ESTABLISHING OVERSEAS DIVISIONS, BUT RIVALRY WAS STILL A FACTOR —WHEN WARNER EXECUTIVE PHIL ROSE ARRIVED IN AUSTRALIA TO BEGIN SETTING UP AN AUSTRALIAN SUBSIDIARY, HE DISCOVERED THAT ONLY ONE WEEK EARLIER ATLANTIC HAD SIGNED A NEW FOUR-YEAR DISTRIBUTION DEAL WITH FESTIVAL RECORDS. IN MARCH 1972, KINNEY MUSIC INTERNATIONAL WAS RENAMED WEA MUSIC INTERNATIONAL. DURING THE 1970S, THE WARNER GROUP BUILT UP A COMMANDING POSITION IN THE MUSIC INDUSTRY. IN 1970, IT BOUGHT ELEKTRA (FOUNDED BY HOLZMAN IN 1950) FOR $10 MILLION, ALONG WITH THE BUDGET CLASSICAL MUSIC LABEL NONESUCH RECORDS. -

Leksykon Polskiej I Światowej Muzyki Elektronicznej

Piotr Mulawka Leksykon polskiej i światowej muzyki elektronicznej „Zrealizowano w ramach programu stypendialnego Ministra Kultury i Dziedzictwa Narodowego-Kultura w sieci” Wydawca: Piotr Mulawka [email protected] © 2020 Wszelkie prawa zastrzeżone ISBN 978-83-943331-4-0 2 Przedmowa Muzyka elektroniczna narodziła się w latach 50-tych XX wieku, a do jej powstania przyczyniły się zdobycze techniki z końca XIX wieku m.in. telefon- pierwsze urządzenie służące do przesyłania dźwięków na odległość (Aleksander Graham Bell), fonograf- pierwsze urządzenie zapisujące dźwięk (Thomas Alv Edison 1877), gramofon (Emile Berliner 1887). Jak podają źródła, w 1948 roku francuski badacz, kompozytor, akustyk Pierre Schaeffer (1910-1995) nagrał za pomocą mikrofonu dźwięki naturalne m.in. (śpiew ptaków, hałas uliczny, rozmowy) i próbował je przekształcać. Tak powstała muzyka nazwana konkretną (fr. musigue concrete). W tym samym roku wyemitował w radiu „Koncert szumów”. Jego najważniejszą kompozycją okazał się utwór pt. „Symphonie pour un homme seul” z 1950 roku. W kolejnych latach muzykę konkretną łączono z muzyką tradycyjną. Oto pionierzy tego eksperymentu: John Cage i Yannis Xenakis. Muzyka konkretna pojawiła się w kompozycji Rogera Watersa. Utwór ten trafił na ścieżkę dźwiękową do filmu „The Body” (1970). Grupa Beaver and Krause wprowadziła muzykę konkretną do utworu „Walking Green Algae Blues” z albumu „In A Wild Sanctuary” (1970), a zespół Pink Floyd w „Animals” (1977). Pierwsze próby tworzenia muzyki elektronicznej miały miejsce w Darmstadt (w Niemczech) na Międzynarodowych Kursach Nowej Muzyki w 1950 roku. W 1951 roku powstało pierwsze studio muzyki elektronicznej przy Rozgłośni Radia Zachodnioniemieckiego w Kolonii (NWDR- Nordwestdeutscher Rundfunk). Tu tworzyli: H. Eimert (Glockenspiel 1953), K. Stockhausen (Elektronische Studie I, II-1951-1954), H. -

Sick Puppies Connect Her Own on Connect, with More and That’S Rounded Us out When We on Saturday, September 7, the Other, Their Own Psyches—And Vate New Ones

K k AUGUST 2013 KWOW HALL NOTES g VOL. 25 #8 H WOWHALL.ORGk release of Tri-Polar (nearly half a up by adding Orange County, million units to date and over 2 California-bred drummer Mark million single sold) and its slew of Goodwin, who they met through a radio hits—the #1 Rock track classified ad following their move “You’re Going Down”, the Top to LA in 2006. Soon after signing Five Modern Rock/Active Rock to Paul Palmer’s indie label through hits “Odd One” and “Riptide” and Virgin Records, a fortuitous video the cross-format anthemic smash pairing with a friend led Sick “Maybe”. Now Connect (out July Puppies to online fame with the 16, 2013), with its melding of song “All The Same” (AKA the room-filling rockers and edgy yet Free Hugs video), which earned an poignant lyrics, is poised to be the astonishing 75-million-plus views Puppies’ best-selling record yet. worldwide, and led to appearances Produced, as was Tri-Polar, by on Oprah, 60 Minutes, CNN, the Rock Mafia production team Good Morning America, and The of Tim James and Antonina Tonight Show with Jay Leno. Armato, Connect also took guid- Drummer Goodwin notes: ance from another, very pure “We’re a career band. We want to source: the trio’s legions of fans. build and take the time to make With face-to-face and online inter- things right. The first time we ever action with Sick Puppies World jammed it was a massive wall of Crew, the band listened when fol- sound; amazing for a trio. -

Gary Numan and Tubeway Army

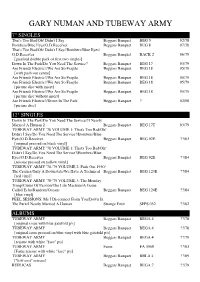

GARY NUMAN AND TUBEWAY ARMY 7" SINGLES That's Too Bad/Oh! Didn't I Say Beggars Banquet BEG 5 02/78 Bombers/Blue Eyes/O.D.Receiver Beggars Banquet BEG 8 07/78 That's Too Bad/Oh! Didn't I Say//Bombers/Blue Eyes/ O.D.Receiver Beggars Banquet BACK 2 06/79 [gatefold double pack of first two singles] Down In The Park/Do You Need The Service? Beggars Banquet BEG 17 03/79 Are Friends Electric?/We Are So Fragile Beggars Banquet BEG 18 05/79 [with push-out centre] Are Friends Electric?/We Are So Fragile Beggars Banquet BEG 18 05/79 Are Friends Electric?/We Are So Fragile Beggars Banquet BEG 18 05/79 [picture disc with insert] Are Friends Electric?/We Are So Fragile Beggars Banquet BEG 18 05/79 [picture disc without insert] Are Friends Electric?/Down In The Park Beggars Banquet ? 02/08 [picture disc] 12" SINGLES Down In The Park/Do You Need The Service?/I Nearly Married A Human 2 Beggars Banquet BEG 17T 03/79 TUBEWAY ARMY '78 VOLUME 1: That's Too Bad/Oh! Didn't I Say/Do You Need The Service?/Bombers/Blue Eyes/O.D.Receiver Beggars Banquet BEG 92E ??/83 [original pressed on black vinyl] TUBEWAY ARMY '78 VOLUME 1: That's Too Bad/Oh! Didn't I Say/Do You Need The Service?/Bombers/Blue Eyes/O.D.Receiver Beggars Banquet BEG 92E ??/84 [reissue pressed on yellow vinyl] TUBEWAY ARMY '78-'79 VOLUME 2: Fade Out 1930/ The Crazies/Only A Downstate/We Have A Technical Beggars Banquet BEG 123E ??/84 [red vinyl] TUBEWAY ARMY '78-'79 VOLUME 3: The Monday Troop/Crime Of Passion/The Life Machine/A Game Called Echo/Random/Oceans Beggars Banquet BEG 124E ??/84 [blue -

Baseball Goods

f I ) ' J. THE' FABMER: JCTjLY 24: 191S riiiiiiiiiiiiiuiiittiiuiiiuiiiiiniiiiiiiiiiHiiimuiiiniiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii normal winds and the rotation of the ANNUAL earth. By reason of the earth's rota- AUCTION CYCLONES CAUSE tion ' a mass moving freely In the northern hemisphere 'In any direction. E3Q9GEP0RT WAS I win do deflected to tne ngnt nana mam OF IN of Its course of movement, and . this m WRECKAGE IS BIG CHANGES deflective force is the the more greater rapid the movement is. 100 50 20 YEARS AGO "Thus the water masses of the Gulf 25Tkf'16. EVENT IN DIEPPE Stream flowing northward from the JULY THE GULF STREAM Strait of Florida have a tendency to I rT&Ken from this Files of The Evenlna move to the eastward; that Is, there MEAT DEPARTMENT. Fanner) will be a pressure In .that direction, ( amimiiiiitatainitmiini Tossed Up By the Sea,'. It Is Washington, July 24. Has the Gulf which will vary in amount according it is a fact that the cholera is stead- Stream changed its course recently? to the rapidity of flow, causing the One Years Ago. held to . - answer Gulf Stream water on the (Hundred ily 'increasing . in New York .' and Havre Merchants Expert opinion is! inclined- to to go deep is the the in - the affirmative. But eastern side of the stream and allow- Brooklyn It rapidly assuming by Government. question water from below to Franliforts & form of an epidemic, and may soon according to this same expert opinion, ing the heavy Bologna re mor- there- - is Unusual in a deflec- come nearer to the surface on the Thomas & Wordm has lately spread over the eountry.