The Uncanny in Howard Hawks's the Big Sleep

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Vertical Files Anderson Reading Room Center for Southwest Research Zimmerman Library

“A” – biographical Abiquiu, NM GUIDE TO THE GENERAL VERTICAL FILES ANDERSON READING ROOM CENTER FOR SOUTHWEST RESEARCH ZIMMERMAN LIBRARY (See UNM Archives Vertical Files http://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmuunmverticalfiles.xml) FOLDER HEADINGS “A” – biographical Alpha folders contain clippings about various misc. individuals, artists, writers, etc, whose names begin with “A.” Alpha folders exist for most letters of the alphabet. Abbey, Edward – author Abeita, Jim – artist – Navajo Abell, Bertha M. – first Anglo born near Albuquerque Abeyta / Abeita – biographical information of people with this surname Abeyta, Tony – painter - Navajo Abiquiu, NM – General – Catholic – Christ in the Desert Monastery – Dam and Reservoir Abo Pass - history. See also Salinas National Monument Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Afghanistan War – NM – See also Iraq War Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Abrams, Jonathan – art collector Abreu, Margaret Silva – author: Hispanic, folklore, foods Abruzzo, Ben – balloonist. See also Ballooning, Albuquerque Balloon Fiesta Acequias – ditches (canoas, ground wáter, surface wáter, puming, water rights (See also Land Grants; Rio Grande Valley; Water; and Santa Fe - Acequia Madre) Acequias – Albuquerque, map 2005-2006 – ditch system in city Acequias – Colorado (San Luis) Ackerman, Mae N. – Masonic leader Acoma Pueblo - Sky City. See also Indian gaming. See also Pueblos – General; and Onate, Juan de Acuff, Mark – newspaper editor – NM Independent and -

For Irn on Schooner

'• ■ i.C; i-k'Jr: ■•rtb ' ' '•■,'■ / o ) i > /jriUrt »• ‘ • yf< . r f 11r<‘» ‘if'i'ff'!• i « I'l < t ■> j 1 v i * ' ’ ■ > ■ • '•i ' A VA AC B DAILY OmODLAflOM •for Ihii MoBtk<«f iu u w y , IMS ' ■— .... ' « ^ .......... 5> of > tbo 2 7Andlt 0 o f CtaoalotioBO. (CtaMUtod Adforllilag oa flMra U .) VOL. U L , NO. 118 . SOUTH BIAN,CHESTER, CONN., FRH)AY, FEBRUARY 1 0 ,1 9 8 8 . (8i:m EN RAGES) PRICE THREE CENt^ PRESm ENT-ELECT ROOSETVSliT VISITS BAHAMAS 18 REBELS KILLED i — ON DUTCH CRUISER a - FOR IRN ON SCHOONER Twenty-ire hjiired When HHTAlirS ENVOY M rio e e n On Stolen SAIUIDESDAY Japanese to Refuse E j ^ Men and Two W o n n Crnisor Refnse To Obey Who b d Started Ont To Ordera— Later Snrrender. Sr RonaU Unkay Will Request of League Look For Misflig Yorth, Brins Rqnrt On War Tokyo, Feb. 10.— (A P )—^An offi-^ maintaining that Japaneie-spon- A re ThemadTes Losfa Not Batavia, Java, Peb. 10.— (A P ) — dal statement that Japan wlU rei sored government in Manchuria, a EIgbteen men were killed and 25 In- ply with an emphatic "no" to a government spokesman said today Heard From For Over 40 juxod aboard the rebeDioua Dutch Debts To hreadent-HecL and that Chinese -u)verelgnty to League of Nations’ request for a Manchuria is ended forever, not cruiser de Zeven Provinden when a statement of Japan’s attitude to withstanding reports that toe b iB R — Yonth Sonfdd Ro* naval fighting plane dropped a London, Feb. -

JREV3.6FULL.Pdf

KNO ED YOUNG FM98 MONDAY thru FRIDAY 11 am to 3 pm: CHARLES M. WEISENBERG SLEEPY I STEVENSON SUNDAY 8 to 9 pm: EVERYDAY 12 midnite to 2 am: STEIN MONDAY thru SATURDAY 7 to 11 pm: KNOBVT THE CENTER OF 'He THt fM DIAL FM 98 KNOB Los Angeles F as a composite contribution of Dom Cerulli, Jack Tynan and others. What LETTERS actually happened was that Jack Tracy, then editor of Down Beat, decided the magazine needed some humor and cre• ated Out of My Head by George Crater, which he wrote himself. After several issues, he welcomed contributions from the staff, and Don Gold and I began. to contribute regularly. After Jack left, I inherited Crater's column and wrote it, with occasional contributions from Don and Jack Tynan, until I found that the well was running dry. Don and I wrote it some more and then Crater sort of passed from the scene, much like last year's favorite soloist. One other thing: I think Bill Crow will be delighted to learn that the picture of Billie Holiday he so admired on the cover of the Decca Billie Holiday memo• rial album was taken by Tony Scott. Dom Cerulli New York City PRAISE FAMOUS MEN Orville K. "Bud" Jacobson died in West Palm Beach, Florida on April 12, 1960 of a heart attack. He had been there for his heart since 1956. It was Bud who gave Frank Teschemacher his first clarinet lessons, weaning him away from violin. He was directly responsible for the Okeh recording date of Louis' Hot 5. -

Appendix I Lunar and Martian Nomenclature

APPENDIX I LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE A large number of names of craters and other features on the Moon and Mars, were accepted by the IAU General Assemblies X (Moscow, 1958), XI (Berkeley, 1961), XII (Hamburg, 1964), XIV (Brighton, 1970), and XV (Sydney, 1973). The names were suggested by the appropriate IAU Commissions (16 and 17). In particular the Lunar names accepted at the XIVth and XVth General Assemblies were recommended by the 'Working Group on Lunar Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr D. H. Menzel. The Martian names were suggested by the 'Working Group on Martian Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr G. de Vaucouleurs. At the XVth General Assembly a new 'Working Group on Planetary System Nomenclature' was formed (Chairman: Dr P. M. Millman) comprising various Task Groups, one for each particular subject. For further references see: [AU Trans. X, 259-263, 1960; XIB, 236-238, 1962; Xlffi, 203-204, 1966; xnffi, 99-105, 1968; XIVB, 63, 129, 139, 1971; Space Sci. Rev. 12, 136-186, 1971. Because at the recent General Assemblies some small changes, or corrections, were made, the complete list of Lunar and Martian Topographic Features is published here. Table 1 Lunar Craters Abbe 58S,174E Balboa 19N,83W Abbot 6N,55E Baldet 54S, 151W Abel 34S,85E Balmer 20S,70E Abul Wafa 2N,ll7E Banachiewicz 5N,80E Adams 32S,69E Banting 26N,16E Aitken 17S,173E Barbier 248, 158E AI-Biruni 18N,93E Barnard 30S,86E Alden 24S, lllE Barringer 29S,151W Aldrin I.4N,22.1E Bartels 24N,90W Alekhin 68S,131W Becquerei -

Persistent Or Repeated Surface Habitability on Mars During the Late Hesperian - Amazonian

Persistent or repeated surface habitability on Mars during the Late Hesperian - Amazonian Edwin S. Kite1,*, Jonathan Sneed1, David P. Mayer1, Sharon A. Wilson2 1. University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, USA (* [email protected]) 2. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, District of Columbia, USA Published in: Geophys. Res. Lett., 44, doi:10.1002/2017GL072660. Key Points: • Alluvial fans on Mars did not form during a short-lived climate anomaly • We use the distribution of observed craters embedded in alluvial fans to place a lower limit on fan formation time of >20 Ma • The lower limit on fan formation time increases to >(100-300) Ma when model estimates of craters completely buried in the fans are included Abstract. Large alluvial fan deposits on Mars record relatively recent habitable surface conditions (≲3.5 Ga, Late Hesperian – Amazonian). We find net sedimentation rate <(4-8) μm/yr in the alluvial-fan deposits, using the frequency of craters that are interbedded with alluvial-fan deposits as a fluvial-process chronometer. Considering only the observed interbedded craters sets a lower bound of >20 Myr on the total time interval spanned by alluvial-fan aggradation, >103-fold longer than previous lower limits. A more realistic approach that corrects for craters fully entombed in the fan deposits raises the lower bound to >(100-300) Myr. Several factors not included in our calculations would further increase the lower bound. The lower bound rules out fan-formation by a brief climate anomaly. Therefore, during the Late Hesperian – Amazonian on Mars, persistent or repeated processes permitted habitable surface conditions. 1. Introduction. Large alluvial fans on Mars record one or more river-supporting climates on ≲3.5 Ga Mars (e.g. -

Ricane Magazines

■' ■■ A;, PAGE TWENTl >»> WEDNESDAY.'SEPTEMBER 7, 1969 iffiattrlTPBffr I fm lb A vence Didiy Nat Preaa Ron Hie Weather for tlw WMfe Bated ronMoot a t D.E8. WaattMa BoMM «iDM4tii.isar . rU r mad wvm taalgU. l.aw dt 13,125 X t« as. Fridor OMMttlt wony, w ant Hemlwr o< ttaa Aadlt «6yh a fn r Mattered ehowera Uk»- Bonon of Obwnlattoa Ijr. Hifk la Ste. M aneheaUr^A City of Village Charm VOL. LXXIX. NO. 289 iCTWENTY PAGES) MANCHESTER, CONN., THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 8, 1960 (OlaMlOed AdvertlBlnc on Page 18) PRICJ^ FIVB CENTS Blasts VN, Belgium Second Group from the pages of the Plans Look at nation^s leading fashion Security Check ricane magazines... and our very .Washington, Sept. 8 (4^--- A second congressional com mittee is Goins to look into own second floor sportswear tJie defection of two U.S. code clerks; , Leopoldville. The C ongo.f^ion* “ "“ rntag the U.N. will A special 5-man subcon^nittee departrnent!... be Ukeh shortly.. of the House Armed Services Com Sept. 8 <i<P)-7-Preinier Patrice 11 16 announcement was issued mittee was formed, yesterday to X Lumumba went before an in the wake of the national assem check on how the Pentagon and angry Senate today to defend bly’s action yesterday voiding at Central Intelilgence Agency SWEATERS FOR '60 tempts by the conservative presi <CIA) ’’rsofult, screen, re-screen Trainmen Ask his, government and two dent and the left-leaning premier Full Force hours later they were cheek and clear their personnel.” to fire each other from their Jobs. -

Ebook < Impact Craters on Mars # Download

7QJ1F2HIVR # Impact craters on Mars « Doc Impact craters on Mars By - Reference Series Books LLC Mrz 2012, 2012. Taschenbuch. Book Condition: Neu. 254x192x10 mm. This item is printed on demand - Print on Demand Neuware - Source: Wikipedia. Pages: 50. Chapters: List of craters on Mars: A-L, List of craters on Mars: M-Z, Ross Crater, Hellas Planitia, Victoria, Endurance, Eberswalde, Eagle, Endeavour, Gusev, Mariner, Hale, Tooting, Zunil, Yuty, Miyamoto, Holden, Oudemans, Lyot, Becquerel, Aram Chaos, Nicholson, Columbus, Henry, Erebus, Schiaparelli, Jezero, Bonneville, Gale, Rampart crater, Ptolemaeus, Nereus, Zumba, Huygens, Moreux, Galle, Antoniadi, Vostok, Wislicenus, Penticton, Russell, Tikhonravov, Newton, Dinorwic, Airy-0, Mojave, Virrat, Vernal, Koga, Secchi, Pedestal crater, Beagle, List of catenae on Mars, Santa Maria, Denning, Caxias, Sripur, Llanesco, Tugaske, Heimdal, Nhill, Beer, Brashear Crater, Cassini, Mädler, Terby, Vishniac, Asimov, Emma Dean, Iazu, Lomonosov, Fram, Lowell, Ritchey, Dawes, Atlantis basin, Bouguer Crater, Hutton, Reuyl, Porter, Molesworth, Cerulli, Heinlein, Lockyer, Kepler, Kunowsky, Milankovic, Korolev, Canso, Herschel, Escalante, Proctor, Davies, Boeddicker, Flaugergues, Persbo, Crivitz, Saheki, Crommlin, Sibu, Bernard, Gold, Kinkora, Trouvelot, Orson Welles, Dromore, Philips, Tractus Catena, Lod, Bok, Stokes, Pickering, Eddie, Curie, Bonestell, Hartwig, Schaeberle, Bond, Pettit, Fesenkov, Púnsk, Dejnev, Maunder, Mohawk, Green, Tycho Brahe, Arandas, Pangboche, Arago, Semeykin, Pasteur, Rabe, Sagan, Thira, Gilbert, Arkhangelsky, Burroughs, Kaiser, Spallanzani, Galdakao, Baltisk, Bacolor, Timbuktu,... READ ONLINE [ 7.66 MB ] Reviews If you need to adding benefit, a must buy book. Better then never, though i am quite late in start reading this one. I discovered this publication from my i and dad advised this pdf to find out. -- Mrs. Glenda Rodriguez A brand new e-book with a new viewpoint. -

Raymond Chandler Retold by Rosalie Kerr

The Big Sleep The Big Sleep by Raymond Chandler retold by Rosalie Kerr 1 Marlowe meets the Sternwoods It was about eleven o'clock in the morning, one day in October. There was no sun, and there were rain−clouds over the distant hills. I was wearing my light blue suit with a dark blue shirt and tie, black socks and shoes. I was a nice, clean, well−dressed private detective. I was about to meet four million dollars. From the entrance hall where I was waiting I could see a lot of smooth green grass and a white garage. A young chauffeur was cleaning a dark red sports−car. Beyond the garage I could see a large greenhouse. Beyond that there were trees and then the hills. There was a large picture in the hall, with some old flags above it. The picture was of a man in army uniform. He had hot hard black eyes. Was he General Sternwood's grand− father? The uniform told me that he could not be the General himself, although I knew he was old. I also knew he had two daughters, who were still in their twenties. While I was studying the picture, a door opened. It was a girl. She was about twenty, small but tough−looking. Her golden hair was cut short, and she looked at me with cold grey eyes. When she smiled, I saw little sharp white teeth. Her face was white, too, and she didn't look healthy. `Tall, aren't you?' she said. `I apologize for growing.' She looked surprised. -

"The Censorship of Sex: a Study of Raymond Chandl Er's the Big

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Érudit Article "The Censorship of Sex: A Study of Raymond Chandl er’s The Big Sleep in Franco’s Spain" Daniel Linder TTR : traduction, terminologie, rédaction, vol. 17, n° 1, 2004, p. 155-182. Pour citer cet article, utiliser l'information suivante : URI: http://id.erudit.org/iderudit/011977ar DOI: 10.7202/011977ar Note : les règles d'écriture des références bibliographiques peuvent varier selon les différents domaines du savoir. Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d'auteur. L'utilisation des services d'Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d'utilisation que vous pouvez consulter à l'URI https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l'Université de Montréal, l'Université Laval et l'Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. Érudit offre des services d'édition numérique de documents scientifiques depuis 1998. Pour communiquer avec les responsables d'Érudit : [email protected] Document téléchargé le 9 février 2017 05:34 The Censorship of Sex: A Study of Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep in Franco’s Spain Daniel Linder A number of Translation Studies scholars have explored manipulation in translated texts and the underlying ideologies that support them. Indeed, the Manipulation School (Theo Hermans, José Lambert and others) emerged early in the short history of the discipline and set out to describe the textual manifestations of manipulation and to elucidate the ideological constructs upon which they rested. -

National Park Service Cultural Landscapes Inventory 2009 Civilian

National Park Service Cultural Landscapes Inventory 2009 Civilian Conservation Corps Haleakala Crater Trails District Haleakala National Park ____________________________________________________ Table of Contents Inventory Unit Summary and Site Plan Inventory Unit Description................................................................................................................ 2 Site Plans......................................................................................................................................... 4 Park Information............................................................................................................................... 7 Concurrence Status Inventory Status ............................................................................................................................... 8 Geographic Information and Location Map Inventory Unit Boundary Description ............................................................................................... 8 State and County ............................................................................................................................. 9 Size .................................................................................................................................................. 9 Boundary UTMS............................................................................................................................... 9 Location Map................................................................................................................................. -

Advances in the Search for Life Hearing Committee On

ADVANCES IN THE SEARCH FOR LIFE HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON SCIENCE, SPACE, AND TECHNOLOGY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION APRIL 26, 2017 Serial No. 115–11 Printed for the use of the Committee on Science, Space, and Technology ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://science.house.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 25–467PDF WASHINGTON : 2017 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON SCIENCE, SPACE, AND TECHNOLOGY HON. LAMAR S. SMITH, Texas, Chair FRANK D. LUCAS, Oklahoma EDDIE BERNICE JOHNSON, Texas DANA ROHRABACHER, California ZOE LOFGREN, California MO BROOKS, Alabama DANIEL LIPINSKI, Illinois RANDY HULTGREN, Illinois SUZANNE BONAMICI, Oregon BILL POSEY, Florida ALAN GRAYSON, Florida THOMAS MASSIE, Kentucky AMI BERA, California JIM BRIDENSTINE, Oklahoma ELIZABETH H. ESTY, Connecticut RANDY K. WEBER, Texas MARC A. VEASEY, Texas STEPHEN KNIGHT, California DONALD S. BEYER, JR., Virginia BRIAN BABIN, Texas JACKY ROSEN, Nevada BARBARA COMSTOCK, Virginia JERRY MCNERNEY, California GARY PALMER, Alabama ED PERLMUTTER, Colorado BARRY LOUDERMILK, Georgia PAUL TONKO, New York RALPH LEE ABRAHAM, Louisiana BILL FOSTER, Illinois DRAIN LAHOOD, Illinois MARK TAKANO, California DANIEL WEBSTER, Florida COLLEEN HANABUSA, Hawaii JIM BANKS, Indiana CHARLIE CRIST, Florida ANDY BIGGS, Arizona ROGER W. MARSHALL, Kansas NEAL P. DUNN, Florida CLAY HIGGINS, Louisiana (II) C O N T E N T S April 26, 2017 Page Witness List ............................................................................................................. 2 Hearing Charter ...................................................................................................... 3 Opening Statements Statement by Representative Lamar S. -

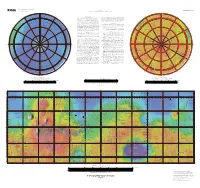

Topographic Map of Mars

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR OPEN-FILE REPORT 02-282 U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Prepared for the NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ADMINISTRATION 180° 0° 55° –55° Russell Stokes 150°E NOACHIS 30°E 210°W 330°W 210°E NOTES ON BASE smooth global color look-up table. Note that the chosen color scheme simply 330°E Darwin 150°W This map is based on data from the Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter (MOLA) 30°W — 60° represents elevation changes and is not intended to imply anything about –60° Chalcoporous v (Smith and others 2001), an instrument on NASA’s Mars Global Surveyor Milankovic surface characteristics (e.g. past or current presence of water or ice). These two (MGS) spacecraft (Albee and others 2001). The image used for the base of this files were then merged and scaled to 1:25 million for the Mercator portion and Rupes map represents more than 600 million measurements gathered between 1999 1:15,196,708 for the two Polar Stereographic portions, with a resolution of 300 and 2001, adjusted for consistency (Neumann and others 2001 and 2002) and S dots per inch. The projections have a common scale of 1:13,923,113 at ±56° TIA E T converted to planetary radii. These have been converted to elevations above the latitude. N S B LANI O A O areoid as determined from a martian gravity field solution GMM2 (Lemoine Wegener a R M S s T u and others 2001), truncated to degree and order 50, and oriented according to IS s NOMENCLATURE y I E t e M i current standards (see below).