1305E Opium in Balkh and Badakhshan CS May 2013.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Draft FSAC Meeting Minutes 8 Jan 2013.Pdf

TYPE OF MEETING: Food Security & Agriculture Cluster meeting DATE & LOCATION Tuesday 8th January, 2013 at WFP Mazar Area Office CHAIR PERSON: WFP NOTE TAKER: Mohammad Masoud Saqib WFP Programme Officer [email protected] WFP, FAO, UNOCHA, WHO, UNICEF, IOM, Islamic Relief, ICRC, ATTENDEES: JOHANNITER, PIN, NRC, SC, ACTED, DACAAR, Aschiana, SHA, ADEO, MAAO, SORA, ASAARO MEETING AGENDA Organization Agenda item presenting 1. Introduction and adoption of previous FSAC meeting WFP 2. FAO Vegetable seeds and hand tools distribution FAO 3. Emergency response capacity (Timeframe) 3 months (Jan – Mar) Projection WFP 4. Inter-agency Winter contingency Plan, WG on People with Special Winter Assistance Need and CERF update UNOCHA 5. Seasonal Livelihood Programming SLP workshop WFP rd rd 6. FSAC Kabul update (3P P IPC Analysis workshop update, 3Ws 3P P Quarter WFP 7. AOB (Input for FSAC newsletter and Partners attendance on FSAC monthly WFP ti MEETING Action points RESPONSIBL MIN ACTION ITEM TIMELINE E PARTY WFP to calculate the questioner format to the partners and 1 partners to response with their food stock availability in the WFP Jan region. FAO to liaise with their country office to see their position in 2 FAO Jan CERF funding application. WFP to send the draft SLP report with the calendar to the FSAC 3 WFP Jan partners for their input 4 5 6 NEXT MEETING DATE LOCATION Monday, 4th February 2013 Islamic Relief Office, Mazar-I-Sharif Afghanistan MEETING MINUTES MINUTE NO: AGENDA: FACILITATOR: 1 Introduction and adoption of previous FSAC WFP Mazar meeting DISCUSSION The meeting was chaired by WFP Mazar Area Office. -

Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces

European Asylum Support Office Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces Country of Origin Information Report August 2020 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces Country of Origin Information Report August 2020 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9485-650-0 doi: 10.2847/115002 BZ-02-20-565-EN-N © European Asylum Support Office (EASO) 2020 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: © Al Jazeera English, Helmand, Afghanistan 3 November 2012, url CC BY-SA 2.0 Taliban On the Doorstep: Afghan soldiers from 215 Corps take aim at Taliban insurgents. 4 — AFGHANISTAN: STATE STRUCTURE AND SECURITY FORCES - EASO COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT Acknowledgements This report was drafted by the European Asylum Support Office COI Sector. The following national asylum and migration department contributed by reviewing this report: The Netherlands, Office for Country Information and Language Analysis, Ministry of Justice It must be noted that the review carried out by the mentioned departments, experts or organisations contributes to the overall quality of the report, it but does not necessarily imply their formal endorsement of the final report, which is the full responsibility of EASO. AFGHANISTAN: STATE STRUCTURE AND SECURITY -

1213E Resilient Oligopoly IP Dec 2012 for Design 29 Dec.Indd

Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit Case Study Series The Resilient Oligopoly: A Political-Economy of Northern Afghanistan 2001 and Onwards Antonio Giustozzi December 2012 Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit Research for a Better Afghanistan This page has been left blank to facilitate double-sided printing Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit Issues Paper The Resilient Oligopoly: A Political-Economy of Northern Afghanistan 2001 and onwards Dr Antonio Giustozzi Funding for this research was provided by the December 2012 the Embassy of Finland in Kabul, Afghanistan Editing and Layout: Sradda Thapa Cover Photographs: (Top to bottom): Bazaar Day in Jowzjan; Marketplace in Shiberghan; New recruits at the Kabul Military Training Center; Mazar-Hayratan highway (all by Subel Bhandari) AREU Publication Code: 1213E AREU Publication Type: Issues Paper © 2012 Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit. Some rights reserved. This publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted only for non-commercial purposes and with written credit to AREU and the author. Where this publication is reproduced, stored or transmitted electronically, a link to AREU’s website (www.areu.org.af) should be provided. Any use of this publication falling outside of these permissions requires prior written permission of the publisher, the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit. Permission can be sought by emailing [email protected] or by calling +93 (0) 799 608 548. Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit About the Author Dr Antonio Giustozzi is an independent researcher who took his PhD at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) and is currently associated with King’s College London, Department of War Studies. -

PROGRAM HIGHLIGHTS February 16 – February 28, 2011

PROGRAM HIGHLIGHTS February 16 – February 28, 2011 EDUCATION School Managers Received Training on Better School Administration: USAID’s Building Education Support Systems for Teachers project has launched capacity- building training to improve school administration in Kabul. The three-day training was provided to 220 school administrators. Facilitated in close collaboration with the Human Resources Department of the Afghan Education Ministry, the training enhances the skills of school administrators and enables them to learn new and better ways of drafting their daily work-plans, develops a good educational environment inside the school among USAID-BESST training workshop, Civil Service teachers and administrative personnel of the schools, and Institute in Kabul. Photo: USAID/BESST trains them to conduct performance appraisals of their staff impartially, and on the basis of their accomplishments. Noorya Ragheb, principal of Maryam Girls’ High School of Kabul said, “subjects discussed and described in this training workshop were very interesting and informative for us.” Ragheb, who has seven years of experience in school administration added, “For a school principal it is very essential to know goals of planning, importance of planning, development of a work-plan, and what a work-plan should be based on, which we learned here. We also learned a lot in the areas of reporting and how to conduct evaluation of staff performance in a just and fair way.” American University of Afghanistan Sets Enrollment Record: University officials announced on February 20, that the American University of Afghanistan (AUAF) has set a new record for enrollment, with 789 students enrolled for spring semester 2011, a 36 percent increase from the previous record of 579, set in fall 2010. -

Afghanistan DECEMBER 2015

Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Ministry of Counter Narcotics Ministry of Counter Narcotics Vienna International Centre, PO Box 500, 1400 Vienna, Austria Banayee Bus Station, Jalalabad Main Road Tel.: (+43-1) 26060-0, Fax: (+43-1) 26060-5866, www.unodc.org 9th District, Kabul, Afghanistan Tel.: (+93) 799891851, www.mcn.gov.af AFGHANISTAN OPIUM SURVEY 2015 OPIUM SURVEY AFGHANISTAN Afghanistan Opium Survey 2015 Cultivation and Production DECEMBER 2015 Afghanistan Opium Survey 2015 ABBREVIATIONS AGE Anti-Government elements ANP Afghan National Police CNPA Counter Narcotics Police of Afghanistan GLE Governor-led eradication ICMP Illicit Crop Monitoring Programme (UNODC) ISAF International Security Assistance Force MCN Ministry of Counter-Narcotics UNODC United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The following organizations and individuals contributed to the implementation of the Afghanistan Opium Survey and to the preparation of this report: Ministry of Counter-Narcotics Prof. Salamat Azimi (Minister), Haroon Rashid Sherzad (Deputy Minister), Mohammad Ibrahim Azhar (Deputy Minister), Mohammad Osman Frotan (Director General Policy and Planning), Sayed Najibullah Ahmadi (Acting Director of Narcotics Survey Directorate), Humayon Faizzad (Provincial Affairs Director), Saraj Ahmad (Deputy Director of Narcotics Survey Directorate), Nasir Ahmad Karimi (Deputy Director of Narcotics Survey Directorate) Mohammad Ajmal Sultani (Statistical Data Analyst), Mohammad Hakim Hayat (GIS & Remote sensing analyst -

Security Report November 2010 - June 2011 (PART II)

Report Afghanistan: Security Report November 2010 - June 2011 (PART II) Report Afghanistan: Security Report November 2010 – June 2011 (PART II) LANDINFO – 20 SEPTEMBER 2011 1 The Country of Origin Information Centre (Landinfo) is an independent body that collects and analyses information on current human rights situations and issues in foreign countries. It provides the Norwegian Directorate of Immigration (Utlendingsdirektoratet – UDI), Norway’s Immigration Appeals Board (Utlendingsnemnda – UNE) and the Norwegian Ministry of Justice and the Police with the information they need to perform their functions. The reports produced by Landinfo are based on information from both public and non-public sources. The information is collected and analysed in accordance with source criticism standards. When, for whatever reason, a source does not wish to be named in a public report, the name is kept confidential. Landinfo’s reports are not intended to suggest what Norwegian immigration authorities should do in individual cases; nor do they express official Norwegian views on the issues and countries analysed in them. © Landinfo 2011 The material in this report is covered by copyright law. Any reproduction or publication of this report or any extract thereof other than as permitted by current Norwegian copyright law requires the explicit written consent of Landinfo. For information on all of the reports published by Landinfo, please contact: Landinfo Country of Origin Information Centre Storgata 33A P.O. Box 8108 Dep NO-0032 Oslo Norway Tel: +47 23 30 94 70 Fax: +47 23 30 90 00 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.landinfo.no Report Afghanistan: Security Report November 2010 – June 2011 (PART II) LANDINFO – 20 SEPTEMBER 2011 2 SUMMARY The security situation in most parts of Afghanistan is deteriorating, with the exception of some of the big cities and parts of the central region. -

March 2017 Sigar-17-32-Sp

Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction SIGAR OFFICE OF SPECIAL PROJECTS SCHOOLS IN BALKH PROVINCE: OBSERVATIONS FROM SITE VISITS AT 26 SCHOOLS MARCH 2017 SIGAR-17-32-SP SIGAR-17-32-SP – Review: Schools in Balkh Province March 28, 2017 The Honorable Wade Warren Acting Administrator, U.S. Agency for International Development Mr. William Hammink Assistant to the Administrator, Office of Afghanistan and Pakistan Affairs, USAID Mr. Herbert Smith USAID Mission Director for Afghanistan Dear Administrator Smith, Mr. Hammink, and Mr. Smith: This report is the second in a series that will discuss our findings from site visits at schools across Afghanistan.1 The 26 schools discussed in this report were either built or rehabilitated using taxpayer funds provided by USAID. As of September 30, 2016, USAID has disbursed about $868 million for education programs in Afghanistan. The purpose of this Special Project review is to determine the extent to which schools purportedly constructed or rehabilitated in Balkh province using USAID funds were open and operational, and to assess their current condition. SIGAR was able to assess the general usability and potential structural, operational, and maintenance issues for each of the 26 schools. Our observations from these site visits indicated that there may be problems with student and teacher absenteeism at several of the schools we visited in Balkh that warrant further investigation by the Afghan government. We also observed that several schools we visited in Balkh lack basic needs, including electricity and clean water, and have structural deficiencies that are affecting the delivery of education. We provided a draft of this report to USAID for comment on February 23, 2017. -

23 September 2010

SIOC – Afghanistan: UNITED NATIONS CONFIDENTIAL UN Department of Safety and Security, Afghanistan Security Situation Report, Week 38, 17- 23 September 2010 JOINT SECURITY ANALYSIS The number of security incidents experienced a dramatic increase over the previous week. This increase included primarily armed clashes, IED incidents and stand-off attacks, and was witnessed in all regions. At a close look, the massive increase is due to an unprecedented peak of security incidents recorded on Election Day 18 September, with incidents falling back to the September average of 65 per day afterwards. Incidents were more widely spread than compared to last year’s Election Day on 20 August 2009, but remained within the year-on-year growth span predicted by UNDSS-A. As last year, no spectacular attacks were recorded on 18 September, as the insurgents primarily targeted the population in order to achieve a low voter turn-out. Kunduz recorded the highest numbers in the NER on Election Day, while Baghlan has emerged as the AGE centre of focus afterwards. In the NR, Faryab accounted for the majority of incidents, followed by Balkh; Badghis recorded the bulk of the security incidents in the WR. The south to east belt accounted for the majority of the overall incidents, with a slight change to the regional dynamics with the SER recording nearly double the number of incidents as the SR, followed by the ER. Kandahar and Uruzgan accounted for the majority of incidents in the SR, while lack of visibility and under-reporting from Hilmand Province continues to result in many of the incidents in the SR remaining unaccounted for. -

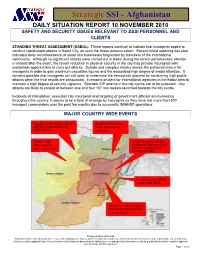

Daily Situation Report 10 November 2010 Safety and Security Issues Relevant to Sssi Personnel and Clients

Strategic SSI - Afghanistan DAILY SITUATION REPORT 10 NOVEMBER 2010 SAFETY AND SECURITY ISSUES RELEVANT TO SSSI PERSONNEL AND CLIENTS STANDING THREAT ASSESSMENT (KABUL): Threat reports continue to indicate that insurgents aspire to conduct coordinated attacks in Kabul City, as such the threat remains extant. Recent threat reporting has also indicated likely reconnaissance of areas and businesses frequented by members of the international community. Although no significant attacks were carried out in Kabul during the recent parliamentary election, or indeed after the event, the recent reduction in physical security in the city may provide insurgents with exploitable opportunities to carry out attacks. Suicide and complex attacks remain the preferred choice for insurgents in order to gain maximum casualties figures and the associated high degree of media attention. It remains possible that insurgents will still seek to undermine the democratic process by conducting high profile attacks when the final results are announced. It remains prudent for international agencies in the Kabul area to maintain a high degree of security vigilance. Sporadic IDF attacks in the city centre are to be expected. Any attacks are likely to consist of between one and four 107 mm rockets launched towards the city centre. Incidents of intimidation, executions by insurgents and targeting of government officials are increasing throughout the country. It seems to be a form of revenge by insurgents as they have lost more than 300 insurgent commanders over the past -

The Political Economy of Education and Health Service Delivery in Afghanistan

The Political Economy Of Education and Health Service Delivery In Afghanistan January 2016 Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit Issues Paper The Political Economy Of Education and Health Service Delivery In Afghanistan AREU January 2016 ISBN: 978-9936-8044-5-6 (ebook) Editing: Victoria Grace Cover photos (Top to bottom): Child receives polio drops as part of the campaign to immunise children under the age of five. Girls and boys playing in school playground. Students checking their result sheets. Doctors from the orthopaedic section of Wazir Akbar Khan Hospital visiting the patients. (Photos by Gulbudding Elham) AREU Publication Code: 1517E This publication may be quoted, cited, or reproduced only for non-commercial purposes and provided that the source is acknowledged. The opinions expessed in this publication are those of the contributors and do not necessarily reflect those of the World Bank or Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit. Where this publication is reproduced, stored, or transmitted electronically, a link to AREU’s website (www.areu.org.af) should be provided. Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit 2016 About the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit The Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU) is an independent research institute based in Kabul. AREU’s mission is to inform and influence policy and practice by conducting high-quality, policy-relevant research and actively disseminating the results, and by promoting a culture of research and learning. To achieve its mission AREU engages with policymakers, civil society, researchers and students to promote their use of AREU’s research and its library, to strengthen their research capacity, and to create opportunities for analysis, reflection, and debate. -

Briefing Note on Fieldwork in Balkh Province, May 2015 Opium Poppy and Rural Livelihoods

AFGHANISTAN RESEARCH AND EVALUATION UNIT Brief Paul Fishstein October 2015 Briefing note on fieldwork in Balkh Province, May 2015 Opium poppy and rural livelihoods Contents 1. Introduction ....................... 1 1. Introduction 2. Agriculture in the Fieldwork Areas in Spring 2015 ................. 2 The following notes describe very initial findings from fieldwork done in 3. Markets ............................. 3 ten villages in Balkh Province’s Chimtal and Char Bolak Districts during the first two weeks of May 2015. Located west of Mazar-e Sharif, these areas 4 . I n n o v a t i o n a n d Te c h n i c a l have been counted among the relatively insecure areas of the province, Change ............................... 4 where households have moved in and out of opium poppy cultivation since it was banned in earnest in 2007. Balkh was classified as “poppy-free” from 5. Large and Economy ................ 5 2007 until 2012/13, when it became a “low level grower,” then was again 6. Development and Assistance ...... 6 considered “poppy-free” in 2013/14. Fieldwork took place during the main spring harvest season, in the larger context of a worsening security situa- 7 . Opium Poppy and tion across much of the north, including neighbouring Sar-e Pul. Security Counter-Narcotics ..................... 6 in some areas of Balkh such as Jar Qalah was considered better due to the creation several years ago, under the sponsorship of Governor Atta, of the Afghan Local Police (ALP), which puts some money in local pockets, even if it raises concerns about long-term stability. Areas of Char Bolak, while not considered completely secure, were seen as better than two years ago. -

Balkh Province

Program for Culture and Conflict Studies BALKH PROVINCE The Program for Culture & Conflict Studies Naval Postgraduate School Monterey, CA Material contained herein is made available for the purpose of peer review and discussion and does not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of the Navy or the Department of Defense. GOVERNOR: ATTA MOHAMMED NOOR POPULATION ESTIMATE: 1,245,000 AREA IN SQUARE KILOMETERS: 16,186.3 (2.5% of Afganistan)1 CAPITAL: Mazar-e-Sharif DISTRICTS: Shortepa, Kaldar, Dawlatabad, Nahri Shahi, Khulm, Chahar Bolak, Balkh, Dihdadi, Mazar-e-Sharof, Marmul, Chimtal, Sholgara, Chahar Kint, Kishindih, Zari (Subdivided within Kishindih in 2005). ETHNIC GROUPS: Chimtal (multi-ethnic, large Arab and Pashtun population, with a significant Hazara minority), Char Bolaq (Pashtun and Hazara, with Turkmen in the North), Dawlat Abad (multi-ethnic with Turkmen minority), Marmul (almost exlusively Tajik), Char Kent (Tajik and Uzbek, with a Sunni Hazara (Kawshi) minority), Zare (Uzbek, Beloch and Hazara).2 RELIGIOUS GROUPS: Sunni, Shi'a, Syyed Shi'a. OCCUPATION OF POPULATION: Agriculture, Trade and Services, Animal Husbandry, some Manufacturing, Remittances, Non-Farm Labor, and Cannibis Trading. CROPS/LIVESTOCK: Sesame, Olives, Sharsham, Wheat, Maize, Potatoes, Rice, Soybeans, Cannabis, Cotton, Tobacco, Cattle, and some Small Ruminants (goats, sheep, etc.) are mainly mamanged by nomadic Kuchis.3,4 LITERACY RATE: Male-38%, Female 19%5 # OF PRIMARY SCHOOLS: 153 Public, 1 Private SECONDARY SCHOOLS: 218 Public, 3 Private HIGH SCHOOLS: 94 Public, 3 Private STUDENT TO TEACHER RATIO: 37:1 COLLEGES/UNIVERSITIES: Balkh University (4,458 Students, 22% Female),6 Balkh Petroleum and Gas Institute (346 Students, 4% Female).7 ACTIVE NGOS IN THE PROVINCE: UN Habitat, PIN, CHA, CARE, ACBAR, ANSO, ActionAid, ADWR, ACTED, ARCS, ARMP/AKDN, ATC, BRAC, CCA, GGA, 1 Staistical Yearbook 2007/2008, CSO, pg.