Cheewee Chew : Determination Dta No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BANKRUPTCY SALE Office Building / Medical / Professional 1 Prospect Park

BANKRUPTCY SALE Office Building / Medical / Professional 1 Prospect Park Winthrop Street 2 5 Utica Church Avenue Avenue FLATBUSH 2 3 4 2 5 Kings County Hospital Beverly Road 2 5 SUNY Downstate Medical Center Lincoln Terrace / Newkirk Arthur S. Somers Park Sutter Ave- Avenue Rutland Rd 2 5 2 3 4 Utica Avenue Holy Cross Saratoga Cemetery Retail Corridor Flatbush Avenue Avenue 2 3 4 2 5 Rockaway BROOKLYN PKWY ROCKAWAY Avenue 2 3 4 UTICA AVE Junius Street FARRAGUT RD 2 3 4 EAST FLATBUSH FOSTER AVE RALPH AVE LINDEN BLVD KINGS HWY 2 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS 7. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 9. PROPERTY OVERVIEW 10. FINANCIAL OVERVIEW 22. LOCATION OVERVIEW 5 EXECUTIVE Summary Rosewood Realty Group is pleased to present the opportunity to purchase 1414 & 1376 Utica Avenue; two properties being sold together in bankruptcy. The properties can be delivered vacant at closing, OR with the current tenant (owner) in place paying rent as a sale-leaseback. The first property located at 1414 Utica Avenue is a 10,083± square foot elevator building on a 4,000± square foot lot. It stands 3 stories plus a lower level / basement, currently in use. The building can be used for office, medical office, or professional use. Additionally, the M1-1 Zoning allows not only for office, but for light industrial use, repair shops, storage facilities, potential retail, funeral home and community facility. The second property located at 1376 Utica Avenue is a 3,000 Square foot lot (30’ x 100’), has curb cut ramps, and is being used as a parking lot. -

BQE in Context: Report from AIANY BQE Task Force | July 2019 1 BQE in Context: Report from AIANY BQE Task Force

BQE in Context: Report from AIANY BQE Task Force | July 2019 1 BQE in Context: Report from AIANY BQE Task Force Introduction................................................................................................................................... 2 Background of BQE Project....................................................................................................... 3 AIANY Workshop I – BQE Planning Goals............................................................................ 4 AIANY Workshop II – Evaluation of BQE Options............................................................... 5 Workshop Takeaways.................................................................................................................. 6 Appendix: AIANY Workshop II Summaries Sub-group A: Atlantic Avenue / Carroll Gardens / Cobble Hill................................ 10 Sub-group B: Brooklyn Heights / Promenade.............................................................. 15 Sub-group C: DUMBO / Bridge Ramps......................................................................... 17 Sub-group D: Larger City / Region / BQE Corridor................................................... 19 BQE Report Credits...................................................................................................................... 26 Early in 2019, members of the American Institute of Architects New York Chapter's (AIANY) Planning & Urban Design and Transportation & Infrastructure committees formed an ad hoc task force to examine issues and opportunities -

Staten Island Overeaters Anonymous (SIOA) Intergroup Invites You to Celebrate

Staten Island Overeaters Anonymous (SIOA) Intergroup Invites You To Celebrate The 45th Anniversary of SIOA Saturday, June 10, 2017 9 AM to 5 PM 9:00 AM to 9:30 AM Registration Program Begins Promptly at 9:30 AM Break for Fellowship and Bring-Your-Own-Lunch Free Refreshments of Coffee, Tea and Bottle Water AvailaBle Throughout the Even The Annual SIOA IG Spring Event Will Be Held at The Michael J. Petrides Education Complex 715 Ocean Terrace Staten Island, New York 10301 Handicap Accessible Plenty of FREE Parking Contact Information Cathy K. Chair of Spring Event Committee 347-407-4360 Angela C. Chair of SIOA IG 917-417-2695 Buddy K Vice Chair of SIOA IG 917-257-0110 SIOA Hotline: 718-605-1393 www.sioa.org This is our Sapphire Anniversary The sapphire includes the qualities of candor, faithfulness, sincerity and truth. It symbolizes wisdom, power and faith The star sapphire is known as the “Stone of Destiny” because travelers believed the gemstone would bring good luck on journey. Directions From Brooklyn, Manhattan, Queens, Long Island, Bronx, New York Take the Verrazano Bridge to the Staten Island Expressway I-278 West to Narrows Road NORTH in Staten Island. Take Exit 13A from I-278 West. Follow Narrows Road North and Little Clove Road to Safety City Boulevard From the Outerbridge Crossing Take the exit onto NY-440 N/W Shore Expy toward NY-440/I-278 Take the Interstate 278 E/Staten Island Expwy E/NY-440 E exit toward Verrazano Br. Merge onto I-278 E/NY-440 N Continue to follow I-278 E Take exit 13 toward Richmond Rd/Clove Rd/Hylan Blvd -

Boy Scout Troop 255 Ten Mile River 2014 Summer Camp

BOY SCOUT TROOP 255 TEN MILE RIVER 2014 SUMMER CAMP DATE/PLACE: Sunday JULY 20th to Saturday JULY 26th (Week 3) TMR CAMP AQUEHONGA Site 3A MEETING : 1:00PM on SUNDAY, JULY 20th at TMR CAMP AQUEHONGA Meet in CAMP AQUEHONGA parking lot. MAKE SURE YOUR SON EATS LUNCH BEFORE WE MEET. Scouts will have dinner at Camp. PICK UP: 10 AM SATURDAY JULY 26th Meet and pick up your child at Camp Aquehonga. Park and go to Site 3A. TRANSPORT: Everyone is responsible for getting to camp on their own. If you wish to car pool, you should make your own arrangement with other Scouts who are going. RULES: A copy of the camp rules is attached. Parents, please read and go over them with your son. Scouts who continually misbehave may be asked to leave and their parents will be called to pick them up immediately. MERIT BADGE: Each Scout should have with them a list of Merit Badges they wish to attempt. (see enclosed advancement schedule) We recommend they sign up for 3 to 6. Scouts must attend all sessions during camp to qualify. Note: some merit badges have prerequisites. WHAT TO BRING: See the attached list of things to bring. Class-A uniforms required for travel to and from camp and for dinner meals. Bring your Class-B uniforms and other clothing enough for 7 days. Bring about $25 spending money. Some merit badges require Scouts to buy craft kits. Scouts are responsible for their own possessions. The camp and leaders are not responsible for losses. -

State of New York in Assembly

STATE OF NEW YORK ________________________________________________________________________ 4911 2019-2020 Regular Sessions IN ASSEMBLY February 5, 2019 ___________ Introduced by M. of A. CUSICK -- read once and referred to the Committee on Transportation AN ACT to amend the state law, the highway law and the administrative code of the city of New York in relation to renaming the Staten Island Expressway the "POW-MIA Memorial Highway" The People of the State of New York, represented in Senate and Assem- bly, do enact as follows: 1 Section 1. Notwithstanding any other law to the contrary, the official 2 name of all that portion of the state highway system located in Richmond 3 county constituting route 440 from Outerbridge Crossing to route 278 4 (West Shore Expressway) and route 278 from the Goethals bridge to the 5 Verrazano-Narrows bridge (Staten Island Expressway) shall be the 6 "POW-MIA Memorial Highway", as such highway is designated in section 7 343-h of the highway law. 8 § 2. Subdivisions 63 and 64 of section 121 of the state law, as added 9 by chapter 16 of the laws of 2012, are amended to read as follows: 10 63. Sixty-third district. In the county of Richmond, that part of the 11 borough of Staten Island bounded by a line described as follows: Begin- 12 ning at the point where the New York/New Jersey border intersects with a 13 line extended northwesterly from Harbor Road, thence southeasterly along 14 said line to Harbor Road, thence southerly along said road to Forest 15 Avenue, thence easterly along said avenue to Summerfield -

Elected Support

ELECTED SUPPORT May 10, 2016 Commissioner Matthew J. Driscoll New York State Department of Transportation 50 Wolf Road Albany, NY 12232 Dear Commissioner Driscoll: We write to ask that the State contribute 38% of the total estimated cost for the Brooklyn Queens Expressway (BQE) Bridge reconstruction project on Interstate 278 (I-278). This funding is necessary for the rehabilitation, reconstruction, and replacement of 1.5 miles of the BQE from Atlantic Avenue to Sands Street. The BQE is a vital connection for the New York City metropolitan area, carrying more than 190,000 vehicles per day. The 1.5 miles between Atlantic Ave. and Sands St. is supported by 21 bridges and a 0.4 mile portion is comprised of a Triple Cantilever structure. According to NYCDOT, the total estimated cost of the project is $1.7 billion. A 38% contribution would cover $659 million of this cost. This contribution level would be consistent with what NYCDOT has said the State has traditionally funded for construction work on City- owned portions of the highway system in New York City, including the Belt Parkway over the Ocean Parkway project, and for protection of the FDR Drive against marine borers. The City and State have already invested billions of dollars in other portions of the BQE, including the Kosciusko Bridge. This section of the BQE, as described by NYSDOT, “is a critical link of I-278, which is the sole interstate facility in Brooklyn connecting the Robert Kennedy Memorial Bridge (previously named the Triborough Bridge), the Bronx and other points to the east, and the Gowanus Expressway, Staten Island, New Jersey and other points to the west.” Comprehensive investment, including in this portion, is critical to ensuring the BQE can continue to serve New Yorkers as it has done for decades. -

Draft Scoping Document Rehabilitation Or

DRAFT SCOPING DOCUMENT REHABILITATION OR RECONSTRUCTION OF THE BROOKLYN-QUEENS EXPRESSWAY ATLANTIC AVENUE TO SANDS STREET KINGS COUNTY P.I.N. X730.56 Rehabilitation or Reconstruction of the BQE, Draft Scoping Document Atlantic Avenue to Sands Street P.I.N. X730.56 TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page I. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 1 II. Project Purpose and Need ................................................................................................................................. 5 Background ............................................................................................................................................................... 5 Need for the Project .................................................................................................................................................. 7 Purpose of the Project ............................................................................................................................................. 10 III. Permits ......................................................................................................................................................... 11 IV. Alternatives .................................................................................................................................................. 12 V. Public Involvement and Agency Coordination ............................................................................................. -

Fact Sheet Number 1 · April 2002

Fact Sheet Number 1 · April 2002 The New York State Department of Transportation (NYSDOT) is about to begin preparation of an Alternatives Analysis/ Environmental Impact Statement to identify the best option to rehabilitate or replace the Kosciuszko Bridge. The study will focus on a 1.1-mile section of the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway (BQE), from Morgan Avenue in Brooklyn to the interchange with the Long Island Expressway in Queens, which includes the Kosciuszko Bridge. As part of Interstate 278, the BQE car- ries large numbers of commercial vehicles. It is a vital link in the region’s transportation network, connecting Brooklyn and Queens and intersecting with the Long Island Expressway, the region’s major east-west highway. The elevated segment of the BQE near the Kosciuszko Bridge, which crosses Kosciuszko Bridge over Newtown Creek Newtown Creek, carries over 190,000 vehi- and rehabilitated in the late 1960s, has best possible way to rehabilitate or replace cles on a typical weekday. In some periods, required frequent road and structural repairs the bridge and this part of the BQE. This up to 30 percent of traffic in this section is since the late 1980s. The concrete deck is must be done while maintaining traffic on trucks. This segment of highway and its worn and the deteriorated steel structure of the highway and avoiding major traffic entrance and exit ramps operate at or near the bridge has needed constant repair. diversions to the local streets and surround- capacity during the morning and afternoon Despite three large repair contracts in the ing communities. rush hours. -

J16/97–0083 WG21/N1121 Date

Doc No: J16/97± 0083 WG21/N1121 Date: 30 September 1997 Project: Programming Language C++ Reply to: Andrew Koenig AT&T Research PO Box 971 180 Park Avenue Room B229 Florham Park, NJ 07932± 0971 [email protected] November 1997 meetingÐtravel information Andrew Koenig 1. Place and time The meeting will be at the Headquarters Plaza Hotel in Morristown, New Jersey, November 9± 14, 1997. The hotel’s phone number is +1 800 225 1942 (± 1941 from inside New Jersey) or +1 973 898 9100, or by fax at +1 973 898 0726. 2. The hotel The Headquarters Plaza Hotel occupies the tallest building in Morristown. It is not affiliated with any chain, but accommodations are similar to major business hotel chains such as Hilton or Marriott. The rooms are newly renovated, and every room has a data jack. There is no surcharge for calls to toll-free numbers. The hotel is part of a complex that includes a multi-screen movie theater, several restaurants, and assorted shops. There are many other restaurants within easy walking distance, with a wide range of cuisines and prices. Also nearby is a commuter train to New York (about an hour each way). As a result, you will probably not need a car during the meeting. However, if you wish to rent a car from Avis (the number of the local branch is +1 973 538 1550) or Enterprise (+1 800 325 8007), they will arrange for you to pick it up and drop it off right at the hotel. There is also a Hertz location nearby. -

![[4910-22-P] DEPARTMENT of TRANSPORTATION Federal](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4455/4910-22-p-department-of-transportation-federal-3984455.webp)

[4910-22-P] DEPARTMENT of TRANSPORTATION Federal

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 11/29/2011 and available online at http://federalregister.gov/a/2011-30431, and on FDsys.gov [4910-22-P] DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION Federal Highway Administration Notice to Rescind the Notice of Intent to develop the Environmental Impact Statement: Kings County, NY AGENCY: Federal Highway Administration (FHWA, United States Department of Transportation (DOT). ACTION: Notice to rescind the Notice of Intent. ----------------------------------------------------------------------- SUMMARY: The FHWA is issuing this rescinded notice to advise the public that the FHWA will not be preparing an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for the proposed project involving approximately 3.8 miles of the Brooklyn- Queens Expressway (BQE), Interstate 278 (I-278) in Kings County, New York (Project Identification Number X729.94). This segment of the BQE referred to as the Gowanus Expressway, extends from Sixth Avenue to the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel and contains 23 structures with a total deck area of approximately 2,000,0000 square feet. A Notice of Intent to prepare an EIS was published in the Federal Register in November 1996. FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Jonathan McDade, Division Administrator, Federal Highway Administration, New York Division, Leo W. O'Brien Federal Building, 7th Floor, Clinton Avenue and North Pearl Street, Albany, New York 12207, Telephone: (518) 431-4127; or Mr. Phillip Eng, P.E., Regional Director, New York State Department of Transportation, Hunters Point Plaza 47-40 21st Street, Long Island City, New York 11101, Telephone: (718) 482-4526. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: The FHWA, in cooperation with the New York State Department of Transportation (NYSDOT) previously intended to prepare an EIS to evaluate alternatives regarding the rehabilitation or reconstruction of the Gowanus Expressway (BQE I-278) in Kings County, New York, from Sixth Avenue to the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel. -

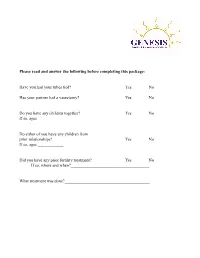

New Patient Packet 2014

! ! ! Please read and answer the following before completing this package: ! ! Have you had your tubes tied? Yes No ! Has your partner had a vasectomy? Yes No ! ! Do you have any children together? Yes No If so, ages ____________ ! ! Do either of you have any children from prior relationships? Yes No If so, ages ____________ ! ! Did you have any prior fertility treatment? Yes No If so, where and when?_____________________________________ ! What treatment was done?________________________________________ ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! DIVISION OF REPRODUCTIVE ENDOCRINOLOGY & INFERTILITY ! PATIENT HISTORY FORM !Date of Visit: _____________ ! PERSONAL INFORMATION First Name: ___________________ M.I.: ___ Last Name: ___________________________ Date of Birth: ___/___ /__ Age: ___ SS# (mandatory): ______________________ Location: (Boro) _____________ Your Employer:____________________________________ Occupation: _________________ Ethnic Background: ________________________________ Religion: ____________________ Phone Numbers: Work: ( ____ ) ____-______ Mobile: ( ____ ) ____-______ Fax: ( ____ ) ____-______ Home Address: ________________ Apt. # : ____ City: _________ State: ____ Zip Code: _____ Home Telephone: ( ____ ) ____-______ E-mail address: _______________________________ Driver’s License Number: _____________________ State: ______________ Partner’s First Name: ________________________ Last Name: _________________________ Date of Birth: ___/___/___ Age: ___ SS#(mandatory): _____________________ Partner’s Employer: __________________________ -

Directions to the Omnicom Group Inc. 2018 Annual Meeting of Shareholders

Directions to the Omnicom Group Inc. 2018 Annual Meeting of Shareholders Meeting Date: Tuesday, May 22, 2018 Meeting Time: 10:00 a.m. Eastern Daylight Time Meeting Place: 15th Floor Conference Center 220 East 42nd Street New York, NY 10017 The 15th Floor Conference Center is located on East 42nd Street in Manhattan between 3rd Avenue and 2nd Avenue. Subway Directions: Take the 4, 5 or 6 train to the Grand Central 42nd Street station. Take exit Lexington Ave & 42nd Street at SW corner. Head east on 42nd Street and proceed to 220 East 42nd Street. From John F. Kennedy International Airport (JFK): Head south on I-678 S and take exit B toward 130th Pl. Keep right at the fork and merge onto 130th Pl. Turn right onto Bergen Rd. At Federal Circle, take the 5th exit onto the I-678 N. ramp. Merge onto I-678 N and take exit 2 toward Rockaway Blvd. Merge onto Van Wyck Expy. Slight left onto Route 678 ramp and merge onto I-678 N. Use the left 2 lanes to take exit 10 to merge onto Grand Central Parkway toward LaGuardia Airport/RF Bridge. Take exit 10E-10W onto I-495 W/Long Island Expy toward Midtown Tunnel. Follow I-495 W and continue onto I-495 W/Queens Midtown Tunnel. Take the Downtown exit and follow signs for Crosstown/37th St/3 Ave. Merge onto East 37th St and turn right onto 3rd Ave. Turn right onto East 42nd St and destination will be on the right. From LaGuardia Airport (LGA): Take LaGuardia Access Rd.