User Experience As a Rhetorical Medium: User at the Intersection of Audience, Reader and Actor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Hate Comic Sans!

I HATE COMIC SANS! It’s Overused It’s Badly used It’s not serious typography Used Incorrectly by Hospitals, Businesses, and Banks, etc. ? “A Computer on Every Desk, In every Home, Running Microsoft Software” the Microsoft Mission statement c. 1980 Computers were expensive Marketed mostly to businesses Expensive Dial up internet Off peak use only on AOL (after 6pm-6am) Screen savers were products Microsoft Scenes After Dark (flying toasters) CD-ROM ‘multimedia’ software MS Beethoven, Schubert, Stravinsky, Strauss MS Ultimate Frank Lloyd Wright MS Wine Guide, MS Dogs, MS Complete Gardening Microsoft Home (1993 Consumer Division) •Goal: To create software for Mums, Dads, and kids Product titles: •Microsoft Flight Simulator* •Microsoft Encarta* •Microsoft Scenes* •Microsoft Creative Writer Wall Street Journal: Aug 24, 1995 • Home computers in US home electronic stores for about $1000 •First affordable computers available • with Windows 95 installed • MSN Online network released to compete with America Online (AOL), Compuserve, Genie etc. • First Generation Internet Explorer released in the Plus Pack for Windows 95 ‘Utopia’ Project Lead: Melinda French (future Mrs. BillG) UI used a simple method of Launching Applications Similar to Hypercard stacks of the late 1980s For children and novice users Release: to coincide with Win95 and 1995 Christmas Season Rover talks in Times New Roman 1994 Microsoft Bob DC Comics: DC Comics The Dark Knight Returns Watchmen DC COMICS: WATCHMEN 1986-87 ILLUSTRATOR/LETTERER : DAVE GIBBONS • -

Microsoft Word 1 Microsoft Word

Microsoft Word 1 Microsoft Word Microsoft Office Word 2007 in Windows Vista Developer(s) Microsoft Stable release 12.0.6425.1000 (2007 SP2) / April 28, 2009 Operating system Microsoft Windows Type Word processor License Proprietary EULA [1] Website Microsoft Word Windows Microsoft Word 2008 in Mac OS X 10.5. Developer(s) Microsoft Stable release 12.2.1 Build 090605 (2008) / August 6, 2009 Operating system Mac OS X Type Word processor License Proprietary EULA [2] Website Microsoft Word Mac Microsoft Word is Microsoft's word processing software. It was first released in 1983 under the name Multi-Tool Word for Xenix systems.[3] [4] [5] Versions were later written for several other platforms including IBM PCs running DOS (1983), the Apple Macintosh (1984), SCO UNIX, OS/2 and Microsoft Windows (1989). It is a component of the Microsoft Office system; however, it is also sold as a standalone product and included in Microsoft Microsoft Word 2 Works Suite. Beginning with the 2003 version, the branding was revised to emphasize Word's identity as a component within the Office suite; Microsoft began calling it Microsoft Office Word instead of merely Microsoft Word. The latest releases are Word 2007 for Windows and Word 2008 for Mac OS X, while Word 2007 can also be run emulated on Linux[6] . There are commercially available add-ins that expand the functionality of Microsoft Word. History Word 1981 to 1989 Concepts and ideas of Word were brought from Bravo, the original GUI writing word processor developed at Xerox PARC.[7] [8] On February 1, 1983, development on what was originally named Multi-Tool Word began. -

PROCESS· ANALYSIS Takes, Only Beautiful Happy Accidents

Process Analysis ..- 293 CHAPTER EIGHT that it was really supposed to be a bike. Who knows? Maybe I'll end up being a police hamster who's been put on "hamster wheel" duty because I'm "too much of a loose cannon" in the field. In improv there are no mis PROCESS· ANALYSIS takes, only beautiful happy accidents. And many of the world's greatest discoveries have been by accident. I mean, look at the Reese's Peanut 9 9 9 Butter Cup, or Botox. -TIN A FEY, Bossypants In a directive process analysis, you typically use the second-person pro noun (you) because you're giving instructions directly to the reader. Some HE essays in this chapter are examples of PROCESS ANALYSIS* or "how times the you is understood, as in a recipe: [you] combine the milk with Allegra Goodman, T to" writing. Basically, there are two kinds of process analysis: directive the eggs, then add .a pinch of salt and the juice of one lemon. In an P· 322, uses the and explanatory. A directive process analysis explains how to make or do second-person to explanatory process analysis, you typically use the third-person tell you how to be something-for instance, how to throw a boomerang. ("Bring the boomerang pronoun (he, she, it) because you're giving information about some- a good writer. back behind you and snap it forward as if you were throwing a baseball." thing to the reader: howstuffworks.com) An explanatory process analysis explains how something works; it tells you what makes the boomerang come back. -

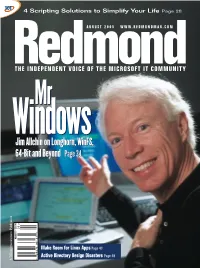

Jim Allchin on Longhorn, Winfs, 64-Bit and Beyond Page 34 Jim

0805red_cover.v5 7/19/05 2:57 PM Page 1 4 Scripting Solutions to Simplify Your Life Page 28 AUGUST 2005 WWW.REDMONDMAG.COM MrMr WindowsWindows Jim Allchin on Longhorn, WinFS, 64-Bit and Beyond Page 34 > $5.95 05 • AUGUST Make Room for Linux Apps Page 43 25274 867 27 Active Directory Design Disasters Page 49 71 Project1 6/16/05 12:36 PM Page 1 Exchange Server stores & PSTs driving you crazy? Only $399 for 50 mailboxes; $1499 for unlimited mailboxes! Archive all mail to SQL and save 80% storage space! Email archiving solution for internal and external email Download your FREE trial from www.gfi.com/rma Project1 6/16/05 12:37 PM Page 2 Get your FREE trial version of GFI MailArchiver for Exchange today! GFI MailArchiver for Exchange is an easy-to-use email archiving solution that enables you to archive all internal and external mail into a single SQL database. Now you can provide users with easy, centralized access to past email via a web-based search interface and easily fulfill regulatory requirements (such as the Sarbanes-Oxley Act). GFI MailArchiver leverages the journaling feature of Exchange Server 2000/2003, providing unparalleled scalability and reliability at a competitive cost. GFI MailArchiver for Exchange features Provide end-users with a single web-based location in which to search all their past email Increase Exchange performance and ease backup and restoration End PST hell by storing email in SQL format Significantly reduce storage requirements for email by up to 80% Comply with Sarbanes-Oxley, SEC and other regulations. -

Teaching Writing Correctional Classroom

ORALITY AND AUDIENCE ANALYSIS: TEACHING WRITING IN THE CORRECTIONAL CLASSROOM Thesis Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of THE UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Master of Arts in English by Timothy Douglas Catalano University of Dayton Dayton, Ohio April 1995 UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON ROESCH LIBRARY 96 02212 APPROVED BY: Dr. Betty lagers Your^kin (Faculty Advisor) Dr. Lawrence Ruff (Faculty Reader) ii © Copyright by Timothy Douglas Catalano All Rights Reserved 1995 ABSTRACT ORALITY AND AUDIENCE ANALYSIS: TEACHING WRITING IN THE CORRECTIONAL CLASSROOM Catalano, Timothy Douglas The University of Dayton, 1995 Advisor: Dr. Betty Rogers Youngkin Walter Ong’s theory of orality and literacy provides a framework for teaching the concept of audience to basic writers in a prison education program. This thesis uses empirical research from a class at Warren Correctional Institute in Lebanon, Ohio, and selected observations of current composition theorists to confirm Ong’s assertion that audience is essential to the student writer’s ability to move from a reliance on speaking to a mastery of writing. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I certainly want to thank Dr. Betty Youngkin for her kindness, insight, and inspiration which she provided not only for my thesis, but for much of my graduate work as well. I would also like to thank Dr. Lawrence Ruff for his contributions to my thesis and to Dr. Stephen Wilhoit, who provided much needed guidance through my graduate career. I would also like to thank my family for early guidance and support, and Father Walter Ong, who provided the groundwork for future exploration into orality. -

The Evolution of Fail Pets : Strategic Whimsy and Brand Awareness in Error Message...Page 1 of 20

The Evolution of Fail Pets : Strategic Whimsy and Brand Awareness in Error Message...Page 1 of 20 About Sponsorship & Advertising Sign In or Register A @ C > = The Evolution of Fail Pets : Strategic Whimsy and Brand Awareness in Error Messages Error message s present a strategic moment for brands. This article looks at the history and evolution of error screens from Microsoft's Blue Screen of Death, to friendly "fail pets" like Twitter's Fail Whale, to more recent approaches. Article No :759 | November 2, 2011 | by Sean Rintel Traditional usability guidelines (http://www.useit.com/alertbox/20010624.html) propose that error messages should be rationally informative. (http://msdn.microsoft.com/en- us/library/aa511267.aspx) However, error messages are also inherently brand messages. http://uxmag.com/articles/the-evolution-of-fail-pets 24/01/2016 The Evolution of Fail Pets : Strategic Whimsy and Brand Awareness in Error Message...Page 2 of 20 (/topics/marketing-and-brand) Branding seeks to create emotional (/topics/emotion) responses to products, and failure evokes emotional responses. Current failure reflects backwards to prior experiences and forward to prospective experiences, and the form of an error message is indicative of the the brand’s sensitivity to the user experience. Error messages are therefore a critical strategic moment in brand awareness and loyalty. Fred Wenzel refers to error mascots, such as Twitter’s (/topics/twitter) Fail Whale (Figure 1) as fail pets (http://fredericiana.com/tag/failpet/page/2/). Fail pets are of particular interest in terms of branding because they can result in brand recognition through earned media. -

Nonprofit Kit for Dummies 4Th Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

NONPROFIT KIT FOR DUMMIES 4TH EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Stan Hutton | 9781118604175 | | | | | Nonprofit Kit For Dummies 4th edition PDF Book Visual Basic 5 for Dummies by Wallace Wang. Statistics For Dummies Accounting For Dummies, 4th edition. Second Life for Dummies by Sarah Robbins. London, England, UK. Access for Windows for Dummies by John Kaufeld. Negotiating for Dummies. Portuguese Phrases For Dummies. Spanish All-in-One for dummies by Consumer Dummies. Electronics Projects for Dummies by Earl Boysen. Pomeranians For Dummies. Honeymoon Vacations for Dummies by Reid Bramblett. Alternative Medicine for Dummies by James Dillard. Sociology For Dummies by Jay Gabler. Norton Internet security for dummies by Greg Holden. Hypnotherapy For Dummies. Gardening Basics for Dummies. Women's Health for Dummies by Pamela Maraldo. Coaching Baseball For Dummies. Gardening for Dummies by Michael MacCaskey. Bipolar Disorder for Dummies by Candida Fink. England, UK. Yoga for Dummies by Georg Feuerstein. Related book awards Axiom Business Book Award. Arthritis for Dummies by Barry Fox. Serving as an ambassador for the organization — making more people aware of its work. Quicken for Windows for Dummies by Stephen L. Allergic Asthma for Dummies by William Berger. With the immense success of that book the company expanded their series into what it is today with such diverse subjects as World History for Dummies, Rabbits for Dummies, Parenting for Dummies, Spirituality for Dummies, and Sex for Dummies. Stan Hutton is a senior program officer at the Clarence E. Orchids for Dummies Prezi for Dummies by Stephanie Diamond. Personal Finance for Dummies by Eric Tyson. Web Design for Dummies by Lisa Lopuck. -

The Writing Process Analysis Essay

09 Assignment 05 - The Writing Process Analysis Essay Overview The Writing Process Analysis Essay is an assignment designed to help you reflect on and analyze your own writing process, as you have developed it over the semester. Your task will be to write an analytical essay examining and explaining the steps that you took while writing your three primary writing assignments in English 101: The Narrative, the Compare-Contrast, and the Argument. In this essay, you will trace your application of each of the steps of the Writing Process—generating ideas, organizing a writing plan, drafting, editing and revising, and proofreading—through each of your three essays. Basic Assignment Requirements The Writing Process Analysis essay must meet the following formatting guidelines: • Be in MLA Manuscript Format o Have 1 inch top, bottom, right and left margins; o Times New Roman 12 font; o Running header with last name and page number; o MLA compliant title block on first page; o All content double spaced. The Writing Process Analysis essay must meet the following content and mechanical guidelines: • Must be at least 1,000 words long; • Must offer a clear and consistent discussion of the writer’s use of the Writing Process in the composition of each of the previous three Major Writing Assignments during the semester; • Must be organized logically with clear topic sentences that clearly introduce each assignment; • Must provide adequate levels of detail and description to support and clearly describe each step of the writing process as it applies to the writer’s work; • Must contain a clear introduction and conclusion that provides overall background for the contents of the portfolio, and sums up the student’s overall English 101 experience; • Must contain none of the following major mechanical errors: o Run-on sentences o Fragments o Tense shifts o Possession errors o Capitalization errors o Subject-verb agreement errors • Must conform to Standard English Grammar requirements for proofreading, usage, and spelling. -

View Bad Ideas About Writing

BAD IDEAS ABOUT WRITING Edited by Cheryl E. Ball & Drew M. Loewe BAD IDEAS ABOUT WRITING OPEN ACCESS TEXTBOOKS Open Access Textbooks is a project created through West Virginia University with the goal of produc- ing cost-effective and high quality products that engage authors, faculty, and students. This project is supported by the Digital Publishing Institute and West Virginia University Libraries. For more free books or to inquire about publishing your own open-access book, visit our Open Access Textbooks website at http://textbooks.lib.wvu.edu. BAD IDEAS ABOUT WRITING Edited by Cheryl E. Ball and Drew M. Loewe West Virginia University Libraries Digital Publishing Institute Morgantown, WV The Digital Publishing Institute believes in making work as openly accessible as possible. Therefore, this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. This license means you can re-use portions or all of this book in any way, as long as you cite the original in your re-use. You do not need to ask for permission to do so, although it is always kind to let the authors know of your re-use. To view a copy of this CC license, visit http://creative- commons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. This book was set in Helvetica Neue and Iowan Old Style and was first published in 2017 in the United States of America by WVU Libraries. The original cover image, “No Pressure Then,” is in the public domain, thanks to Pete, a Flickr Pro user. -

3 Modes of Writing in KCAS

qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqw ertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwert yuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiAddressing Three Modes of Writing Kentucky Core Academic Standards in the 21st Century opasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopa Tips for Understanding Standards, Instruction & Assessment sdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdf ghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjWinter 2012 Office of Next-Generation Learners klzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklz xcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcv bnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbn mqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmq wertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwe rtyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwerty uiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuio pasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopas dfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfg hjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjk lzxcvbnmrtyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbn Introduction This guidebook was developed to help Kentucky educators provide students with opportunities to develop into confident, independent and proficient writers who are prepared for college and/or careers. The guidebook is organized around the three modes of writing in the Kentucky Core Academic Standards (KCAS). Within each of three sections, readers will see information about the standards, instruction to support the teaching of the standards and assessment. Information about the formative assessment process will be emphasized; however, readers also will find embedded details about Kentucky’s on- demand writing assessment administered in grades 5, 6, 8, 10 and 11. Since each section of the guidebook is organized around one of the modes of writing in KCAS, readers will read each section with the understanding that the modes of writing often are -

Paratextual and Bibliographic Traces of the Other Reader in British Literature, 1760-1897

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Theses and Dissertations 9-22-2019 Beyond The Words: Paratextual And Bibliographic Traces Of The Other Reader In British Literature, 1760-1897 Jeffrey Duane Rients Illinois State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Educational Methods Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Rients, Jeffrey Duane, "Beyond The Words: Paratextual And Bibliographic Traces Of The Other Reader In British Literature, 1760-1897" (2019). Theses and Dissertations. 1174. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/1174 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BEYOND THE WORDS: PARATEXTUAL AND BIBLIOGRAPHIC TRACES OF THE OTHER READER IN BRITISH LITERATURE, 1760-1897 JEFFREY DUANE RIENTS 292 Pages Over the course of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, compounding technological improvements and expanding education result in unprecedented growth of the reading audience in Britain. This expansion creates a new relationship with the author, opening the horizon of the authorial imagination beyond the discourse community from which the author and the text originate. The relational gap between the author and this new audience manifests as the Other Reader, an anxiety formation that the author reacts to and attempts to preempt. This dissertation tracks these reactions via several authorial strategies that address the alienation of the Other Reader, including the use of prefaces, footnotes, margin notes, asterisks, and poioumena. -

Writing Emotions

Ingeborg Jandl, Susanne Knaller, Sabine Schönfellner, Gudrun Tockner (eds.) Writing Emotions Lettre 2017-05-15 15-01-57 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 0247461218271772|(S. 1- 4) TIT3793_KU.p 461218271780 2017-05-15 15-01-57 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 0247461218271772|(S. 1- 4) TIT3793_KU.p 461218271780 Ingeborg Jandl, Susanne Knaller, Sabine Schönfellner, Gudrun Tockner (eds.) Writing Emotions Theoretical Concepts and Selected Case Studies in Literature 2017-05-15 15-01-57 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 0247461218271772|(S. 1- 4) TIT3793_KU.p 461218271780 Printed with the support of the State of Styria (Department for Health, Care and Science/Department Science and Research), the University of Graz, and the Faculty of Arts and Humanities University of Graz. An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access for the public good. The Open Access ISBN for this book is 978-3-8394-3793-3. More information about the initiative and links to the Open Access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No- Derivs 4.0 (BY-NC-ND) which means that the text may be used for non-commercial purposes, provided credit is given to the author. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. To create an adaptation, translation, or derivative