Montreal Technoparc Submission (SEM-03-005)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Irena Karafilly Takes Us Back to Montreal, 1970

Fondation Foundation Help Generations help kids generationsfoundation.com 514-933-8585 MARCH 2017 VOL. XXXl N O 4 GUIDE TO SENIOR LIVING Irena Karafilly takes us back to Montreal, 1970 MONTREAL’S LEADING BUYER OF RARE COINS SINCE 1928 WE WILL GIVE YOU TOP DOLLAR FOR ALL YOUR OLD COINS & PAPER MONEY Canada, USA, World, Ancient and Medieval coins Silver, Gold and Platinum wanted in coins, bars or jewellery 1117 Ste Catherine W, Suite 700, Montreal 514-289-9761 carsleys.comsleys.com Re- this issue’s theme(s) Salinas, Ec. — The theme this issue We accompany Irwin Block along is two-fold: It’s not only our semi-an- the streets of Havana as he re-visits nual retirement living issue but we are Cuba and reports on life as it is for exploring the theme of re-. the majority of Cubans in the wake of You’ve got it: it’s the prefix re-. At Fidel’s death. In another feature story, he this 50+ stage in our lives, we do a lot interviews Joyce Wright, who is vaca- A diamond in the heart of Beaconsfi eld of re-jigging, re-invention, re-direction, tioning here in Salinas, Ecuador, about re-living, regretting, replenishing, and how she and her siblings built a class- A carefree living experience rejuvenating through travel, courses, room in Mexico. and relationships. Some have chosen As for my own re-invention here in to re-direct rather than retire. Some- Salinas, I am teaching art to children in times we re-educate ourselves about my basic Spanish as a volunteer in an new trends and re-think our die-hard educational centre that enriches chil- opinions. -

Toward Sustainable Municipal Water Management

Montréal’s Green CiTTS Report Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Cities Initiative TOWARD SUSTAINABLE MUNICIPAL WATER MANAGEMENT OCTOBER 2013 COORDINATION AND TEXT Rémi Haf Direction gestion durable de l’eau et du soutien à l’exploitation Service de l’eau TEXT Monique Gilbert Direction de l’environnement Service des infrastructures, du transport et de l’environnement Joanne Proulx Direction des grands parcs et du verdissement Service de la qualité de vie GRAPHIC DESIGN Rachel Mallet Direction de l’environnement Service des infrastructures, du transport et de l’environnement The cover page’s background shows a water-themed mural PHOTOS painted in 2013 on the wall of a residence at the Corporation Ville de Montréal d’habitation Jeanne-Mance complex in downtown Montréal. Air Imex, p.18 Technoparc Montréal, p.30 Soverdi, p.33 Journal Métro, p.35 Thanks to all Montréal employees who contributed to the production of this report. CONTENTS 4Abbreviations 23 Milestone 4.1.2: Sewer-Use Fees 24 Milestone 4.1.3: Cross-Connection Detection Program 6Background 25 Milestone 4.2: Reduce Pollutants from Wastewater Treatment Plant Effl uent 7Montréal’s Report 27 Milestone 4.3: Reduce Stormwater Entering Waterways 8 Assessment Scorecard Chart 28 Milestone 4.4: Monitor Waterways and Sources of Pollution 9Montréal’s Policies 30 PRINCIPLE 5. WATER PROTECTION PLANNING 11 PRINCIPLE 1. WATER CONSERVATION AND EFFICIENCY 31 Milestone 5.1: Adopt Council-Endorsed Commitment to Sustainable 12 Milestone 1.1: Promote Water Conservation Water Management 13 Milestone 1.2: Install Water Meters 32 Milestone 5.2: Integrate Water Policies into Land Use Plan 14 Milestone 1.4: Minimize Water Loss 33 Milestone 5.4: Adopt Green Infrastructure 15 PRINCIPLE 2. -

Spring Office Market Report 2018 Greater Montreal

SPRING OFFICE MARKET REPORT 2018 GREATER MONTREAL Image Credit: Avison Young Québec Inc. PAGE 1 SPRING 2018 OFFICE MARKET REPORT | GREATER MONTREAL SPRING OFFICE MARKET REPORT 2018 GREATER MONTREAL Office market conditions have Class-A availability Downtown been very stable in the Greater Montreal reached 11.7% at the Montreal Area (GMA) over the end of the first quarter, which past year, but recent news lead represents an increase of only 20 to believe this could change basis points year-over-year. drastically over the years to come as major projects were announced Landlords who invested in their and the construction of Montreal’s properties and repositioned their Réseau Express Métropolitain assets in Downtown Montreal over (REM) began. New projects and the past years are benefiting from future developments are expected their investments as their portfolios to shake up Montreal’s real estate show more stability and success markets and put a dent in the than most. stability observed over the past quarters. It is the case at Place Ville Marie, where Ivanhoé Cambridge is Even with a positive absorption of attracting new tenants who nearly 954,000 square feet (sf) of are typically not interested in space over the last 12 months, the traditional office space Downtown total office availability in the GMA Montreal, such as Sid Lee, who will remained relatively unchanged be occupying the former banking year-over-year with the delivery of halls previously occupied by the new inventory, reaching 14.6% at Royal Bank of Canada. Vacancy and the end of the first quarter of 2018 availability in the iconic complex from 14.5% the previous year. -

Public Finance in Montréal: in Search of Equity and E"Ciency

IMFG P$%&'( )* M+*,.,%$/ F,*$*.& $*0 G)1&'*$*.& N). 34 • 5637 Public Finance in Montréal: In Search of Equity and E"ciency Jean-Philippe Meloche and François Vaillancourt Université de Montréal IMFG Papers on Municipal Finance and Governance Public Finance in Montréal: In Search of Equity and Efficiency By Jean-Philippe Meloche and François Vaillancourt Institute on Municipal Finance & Governance Munk School of Global Affairs University of Toronto 1 Devonshire Place Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5S 3K7 e-mail contact: [email protected] http://munkschool.utoronto.ca/imfg/ Series editor: Philippa Campsie © Copyright held by authors, 2013 ISBN 978-0-7727-0917-2 ISSN 1927-1921 The Institute on Municipal Finance and Governance (IMFG) at the Munk School of Global Affairs at the University of Toronto focuses on developing solutions to the fiscal and governance problems facing large cities and city-regions. IMFG conducts original research on Canadian cities and other cities around the world; promotes high-level discussion among Canada’s government, academic, corporate, and community leaders through conferences and roundtables; and supports graduate and post-graduate students to build Canada’s cadre of municipal finance and governance experts. It is the only institute in Canada that focuses solely on municipal finance issues and large cities and city-regions. IMFG is funded by the Province of Ontario, the City of Toronto, Avana Capital Corporation, and TD Bank. The IMFG Papers on Municipal Finance and Governance are designed to disseminate research that is being undertaken in academic circles in Canada and abroad on municipal finance and governance issues. The series, which includes papers by local as well as international scholars, is intended to inform the debate on important issues in large cities and city-regions. -

2019-2020 SCHOOL GROUP GUIDE Winter Or Summer, 7 TOURIST ATTRACTIONS Day Or Night, Montréal Is Always Bustling with Activity

2019-2020 SCHOOL GROUP GUIDE Winter or summer, 7 TOURIST ATTRACTIONS day or night, Montréal is always bustling with activity. 21 ACTIVITIES Known for its many festivals, captivating arts and culture 33 GUIDED TOURS scene and abundant green spaces, Montréal is an exciting metropolis that’s both sophisticated and laid-back. Every year, it hosts a diverse array of events, exhibitions 39 PERFORMANCE VENUES and gatherings that attract bright minds and business leaders from around the world. While masterful chefs 45 RESTAURANTS continue to elevate the city’s reputation as a gourmet destination, creative artists and artisans draw admirers in droves to the haute couture ateliers and art galleries that 57 CHARTERED BUS SERVICES line the streets. Often the best way to get to know a place is on foot: walk through any one of Montréal’s colourful and 61 EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS vibrant neighbourhoods and you’ll discover an abundance of markets, boutiques, restaurants and local cafés—diverse expressions of Montréal’s signature joie de vivre. The energy 65 ACCOMMODATIONS is palpable on the streets, in the metro and throughout the underground pedestrian network, all of which are remarkably safe and easy to navigate. But what about the people? Montréalers are naturally charming and typically bilingual, which means connecting with locals is easy. Maybe that’s why Montréal has earned a spot as a leading international host city. From friendly conversations to world-class dining, entertainment and events, there are a lot of reasons to love Montréal. All email and website addresses are clickable in this document. Click on this icon anywhere in the document to return to the table of contents. -

The NOS Terminal Grain Elevator In

The NOSTerminal Grain Elevator in the Port of Montreal: Monument in a Shifting Landscape Nathalie W. Senécal The Department of Art History Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts at Concordia University Montreai, Quebec, Canada O Nathalie H. Senécal, 2001 National Libraiy Bibliothèque nationale 1+1 ofcmada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibiiographic Services secvices bibliographiques The author has granted a non- L'autem a accordé une licence non exclrisive iicence allowing the excIuSive parnettant B la National Library of Canada to BÏbliothèque nationale du Canada de repradpce, loan, disûibute or seIl reproduire, prêter, cbûi'b~erou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. La forme de mkr~fiche/nim.de reproduction sur papier on sur format électroniquee. The author retains ownership of the L'autem conserve la propriété du copyright in tbis thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts hmit Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantieIs may be priated or otherwike de ceiIe-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. iii Abstract The No. 5 Elevator and the Port of Montreal: Monument in a Shifting Landscape The No. 5 terminal elevator in the port of Montreal is the last of a group of colossal machines for moving and storing grain that once hed the waterhnt in fiont of Old Montreal. The tenninal elevators of the port of Montreai were the culmination-point of the national infiastructures of grain shipping that helped to make Montreal the most important grain-exportllig port in the world during the 1920s and 1930s. -

Griffintown Golroo Mofarrahi

Griffintown Golroo Mofarrahi Post-professional graduate program in Cultural Landscapes School of Architecture McGill University August 2009 Report Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Master ofArchitecture Golroo Mofarrahi, 2009 Abstract: This study originates from observation that urban neigh bourhoods are in continuous transition as the economy ebbs and flows. Residential neighbour- hoods will either collapse or redlined for new development as their residents start to move out (The Lure of the Local, 202). At the same time, coun- try towns are being abandoned, working class neighbourhoods are further ghettoized and steel towns are rusting in decay as “deserted downtowns con- trast with exurban building booms” (The Lure of the Local, 202). An example of this type of neighbourhood is Griffintown, which was once a working class neighbourhood squeezed between Saint Gabriel farm and the suburbs of Recollets and Victoria town in Montreal. Griffintown was an industrial and residential district. It was urbanised in the 19th century and gradually decayed through the 20th century. As an industrial district it saw the birth of very first large factories of Canada and was known as the industrial heartland of Canada. The area was of great interest to most developers, and various projects have been proposed for this area. This report addresses the follow ing question: How does the extent artefact system in Griffintown represent tangible evidence of the way of life before forced resettlement, and are there any artefacts worth preserving in Griffintown, an area slated for imminent development? I Résumé: Cette étude trouve son origine dans la notion selon laquelle les quartiers ur- bains sont engagés dans un cycle de croissance et de déclin soumis aux aléas de la conjoncture économique. -

Montreal Port Truckers Can Tap App for Terminal Wait Times

Wednesday October 5, 2016 Log In Register Subscribe Need Help? Search JOC.COM Special Topics Ports Sailings Maritime Breakbulk Trucking Logistics Rail & Intermodal Government Economy Air Cargo Trade Montreal port truckers can tap app for terminal wait times Dustin Braden, Assistant Web Editor, JOC.com (/users/dbraden) | Oct 04, 2016 4:23PM EDT Print (http://www.joc.com/subscribeprint?width=500&height=500&iframe=true) More on JOC Shenzhen port enacts lowsulfur fuel rule ahead of schedule (/regulationpolicy/transportation (/regulation regulations/international policy/transportatrtiaonnsportationregulations/shenzhen regulations/interpnoarttioennaalctslowsulfurfuelruleahead transportation schedule_20161005.html) International regulations/shenTzrahnesnportation Regulations (/regulation portenacts policy/transportation lowsulfurfuel regulations/international ruleahead transportationregulations) schedule_20161005.html) Russia to overhaul trucking regulations to stabilize market (/regulationpolicy/transportation regulations/international Trucks enter the Port of Montreal, which hopes to reduce congestion and turn times via the collection and distribution of realtime (/regulation transportationregulations/russia truck traffic data. policy/transportation regulations/interonvaetirohnaaulltruckingregulationsstabilize transportation market_20161005.html) International Drayage drivers serving the Port of Montreal can track terminal wait times via a new app aimed at improving gate regulations/russTiara nsportation Regulations (/regulation overhaul policy/transportation fluidity and reducing greenhouse gas emissions. trucking regulations/international regulations transportationregulations) stabilize The Trucking PORTal application relies on Bluetooth, radiofrequency identification, and license plate readers to market_20161005.html) measure truck locations and turn times within the port’s terminals with the ultimate goal of reducing trucker wait Pipavav volume under pressure as intraAsia times. -

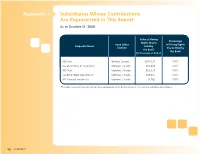

Subsidiaries Whose Contributions Are Represented in This Report As at October 31, 2009

Appendix 1 Subsidiaries Whose Contributions Are Represented In This Report As at October 31, 2009 Value of Voting Percentage Rights Shares Head Office of Voting Rights Corporate Name Held by Location Shares Held by the Bank1 the Bank (In thousands of dollars) B2B Trust Toronto, Canada $286,530 100% Laurentian Trust of Canada Inc. Montreal, Canada $85,409 100% LBC Trust Montreal, Canada $62,074 100% Laurentian Bank Securities Inc. Montreal, Canada $39,307 100% LBC Financial Services Inc. Montreal, Canada $4,763 100% 1 The book value of shares with voting rights corresponds to the Bank’s interest in the equity of subsidiary shareholders. 23 APPENDIX Appendix 2 Employee Population by Province and Status As at October 31, 2009 Province Full-Time Part-Time Temporary Total Alberta 10 – – 10 British Columbia 6 – – 6 Newfoundland 1 – – 1 Nova Scotia 1 – – 1 Ontario 369 4 81 454 Québec 2,513 617 275 3,405 TOTAL 2,900 621 356 3,877 24 APPENDIX Appendix 3 Financing by commercial client loan – Amounts authorized during the year As at October 31, 2009 0 − 25,000 − 100,000 − 250,000 − 500,000 − 1,000,000 − 5,000,000 Province Total 24,999 99,999 249,999 499,999 999,999 4,999,999 and over British Columbia Authorized amount 168,993 168,993 Number of clients 1 1 New Brunswick Authorized amount Number of clients Ontario Authorized amount 151,900 1,024,068 3,108,000 8,718,154 30,347,394 189,266,928 296,349,931 528,966,375 Number of clients 16 18 20 26 43 90 29 242 Québec Authorized amount 16,050,180 92,265,280 172,437,714 229,601,369 267,927,253 689,934,205 -

Environmental Assessment Summary Report

Environmental Assessment Summary Report Project and Environmental Description November 2012 Transport Canada New Bridge for the St. Lawrence Environmental Assessment Summary Report Project and Environmental Description November 2012 TC Ref.: T8080-110362 Dessau Ref.: 068-P-0000810-0-00-110-01-EN-R-0002-0C TABLE OF CONTENT GLOSSARY......................................................................................................................................VII 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 PROJECT BACKGROUND AND LOCATION .................................................................... 1 1.2 LEGAL FRAMEWORK FOR THE ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT............................. 2 2 PROJECT DESCRIPTION............................................................................................................7 2.1 PLANNED COMPONENTS AND VARIATIONS................................................................. 7 2.1.1 Reconstruction and expansion of Highway 15 (Component A) .......................................... 7 2.1.2 New Nuns’ Island Bridge (Component B) ........................................................................... 7 2.1.3 Work on Nuns’ Island (Component C) ................................................................................ 8 2.1.4 The New Bridge for the St. Lawrence (Component D) ..................................................... 11 2.1.4.1 Components D1a and D1b: crossing the St. Lawrence -

Directory of Community and Social Services

Directory of Community and Social Services MRC DE LA VALLÉE-DU-RICHELIEU 2-1-1 www.211qc.ca Summary Child and Family 1 Child welfare 2 Family Support 2 Community Action 4 Advisory and citizen action organizations 5 Community development 6 Information and referral 6 Volunteering and volunteer centres 7 Education 9 Dropout 10 Homework assistance and tutoring 10 Language courses 11 Literacy 11 Employment and Income 12 Business development 13 Employment support and training 13 Employment support for immigrants 14 Employment support for youth 14 Government services 15 Tax clinics 15 Vocational rehabilitation and disability-related employment 16 Food 17 Collective kitchens 18 Community gardens and markets 18 Food Assistance 19 Government services 20 Municipal services 21 Health 24 Hospitals, CLSC and community clinics 25 Palliative care 25 Homelessness 27 Mobile units and street work 28 Immigration and cultural communities 29 Government services 30 Multicultural centres and associations 30 Indigenous Peoples 31 Government Services 32 Intellectual Disability 33 Autism, PDD, ADHD 34 Recreation and camps 34 Support and integration organizations 35 Justice and Advocacy 36 Information and legal assistance 37 Material Assistance and Housing 38 Emergency 39 Housing cooperatives and corporations 39 Thrift stores 40 Mental Health and addictions 43 Addiction prevention 44 Community support in mental health 44 Self-help groups for addiction issues 44 Summary Physical Disability 46 Advocacy for people with a physical disability 47 Recreation and camps -

Montreal: Restaurants and Activities USNCCM14

Montreal: Restaurants and Activities USNCCM14 Montreal, July 17-20, 2017 Restaurants Montreal is home to a wide variety of delicious cuisines, ranging from fine dining foodie delicacies to affordable gems. Below you will find a guide to many of the best restaurants near the Palais des Congrès (PDC). Restaurants were grouped according to price and ordered according to distance from the convention center. Prices shown are the price range of main courses within a restaurant’s menu. Casual Dining Located on the Border of Old Montreal and China Town, there are many casual dining places to be found near the convention center, particularly to the north of it. < 1 km from PDC Mai Xiang Yuan, 1082 Saint-Laurent Boulevard, $10-15, 500 m Made-to-order Chinese dumplings made with fillings such as lamb, curried beef, and pork. Niu Kee, 1163 Clark St., $10-25, 550 m Authentic Chinese Restaurant, specializing in Szechwan Dishes. Relaxed, intimate setting with large portions and a wide variety of Szechwan dishes available. LOV (Local Organic Vegetarian), 464 McGill St., $10-20, 750 m Sleek, inspired vegetarian cuisine ranging from veggie burgers & kimchi fries to gnocchi & smoked beets. Restaurant Boustan, 19 Sainte-Catherine St. West, $5-12, 800 m As the Undisputed king of Montreal food delivery, this Lebanese restaurant offers tasty pita wraps until 4:00 A.M. For delivery, call 514-844-2999. 1 to 2 km from PDC La Pizzaiolle, 600 Marguerite d'Youville St., $10-20, 1.1 km Classic pizzeria specializing in thin-crust, wood-fired pies, and other Italian dishes.