Dissertation Study on the Airline Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Annual Report 2004/05

ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES Annual Report 2004-05 WWW.ETHIOPIANAIRLINES.COM ANNUAL REPORT 2004-05 building CONTENTS on the FUTURE Management Board of Ethiopian Airlines .................................. 2 CEO’s Message............................................................................................. 3 Ethiopian Airlines Management Team ......................................... 4 Embarking on a long-range reform I. Investing for the future Continent .................................... 5 II. Continuous Change .............................................................. 5 III. Operations Review ............................................................... 5 IV. Measures to Enhance Profitability .................................. 7 V. Human Resource Development ....................................... 10 VI. Fleet Planning and Financing .......................................... 11 VII. Information Systems .......................................................... 11 VIII. Tourism Promotion ............................................................ 11 IX. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Measures ....... 12 Finance ............................................................................................................. 13 Auditors Report and Financial Statements ................................ 22 Domestic Route Map .............................................................................. 40 Ethiopian Airlines Offices ...................................................................... 41 International Route Map ...................................................................... -

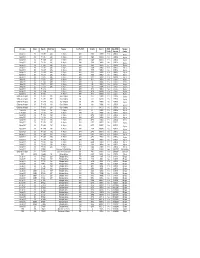

Final AFI RVSM Approvals 05 June 08

Mfr & Type Variant Reg. No. Build Year Operator Acft Op ICAO Serial No Mode S RVSM Date RVSM Operator Yes/No Approval Country Boeing 737 800 7T - VJK 2000 Air Algérie DAH 30203 0A0019 Yes 23/01/02 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VJL 2000 Air Algérie DAH 30204 0A001A Yes 23/01/02 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VJM 2000 Air Algérie DAH 30205 0A001B Yes 23/01/02 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VJN 2000 Air Algérie DAH 30206 0A0020 Yes 23/01/02 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VJQ 2002 Air Algérie DAH 30207 0A0021 Yes 23/01/02 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VJP 2001 Air Algérie DAH 30208 0A0022 Yes 23/01/02 Algeria Boeing 737 600 7T - VJR 2002 Air Algérie DAH 30545 0A0025 Yes 01/06/02 Algeria Boeing 737 600 7T - VJS 2002 Air Algérie DAH 30210 0A0026 Yes 18/06/02 Algeria Boeing 737 600 7T - VJT 2002 Air Algérie DAH 30546 0A0027 Yes 18/06/02 Algeria Boeing 737 600 7T - VJU 2002 Air Algérie DAH 30211 0A0028 Yes 06/07/02 Algeria Airbus 330 202 7T - VJV 2005 Air Algérie DAH 0644 0A0044 Yes 31/01/05 Algeria Airbus 330 202 7T - VJW 2005 Air Algérie DAH 647 0A0045 Yes 05/03/05 Algeria Airbus 330 202 7T - VJY 2005 Air Algérie DAH 653 0A0047 Yes 20/03/05 Algeria Airbus 330 202 7T - VJX 2005 Air Algérie DAH 650 0A0046 Yes 20/03/05 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VKA Air Algérie DAH 34164 0A0049 Yes 23/07/05 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VKB Air Algérie DAH 34165 0A004A Yes 22/08/05 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VKC Air Algérie DAH 34166 0A004B Yes 24/08/05 Algeria Gulfstream Aerospace SP 7T - VPC 2001 Gouv of Algeria IGA 1418 0A4009 Yes 27/07/05 Algeria Gulfstream Aerospace SP -

CHAPTER 11: Civil Aviation Industry

CHAPTER 11: Civil Aviation Industry 11.1 AIR TRANSPORT The main objective of the decision was IN AFRICA the gradual liberalization of scheduled and non-scheduled intra-African air services, The poor state of land transport infrastructure abolishing limits on the capacity and and freight and passenger services in much frequency of international air services within of Africa appears to offer a promising Africa, liberalizing fares and universally opportunity for the further development of air granting traffi c rights up to the ”fi fth freedom transport services throughout the continent. At of the air.”2 Signatory states were obliged to this stage, the key policy issues for Zimbabwe ensure the fair opportunity to compete on a are the ways it can benefi t from the ongoing nondiscriminatory basis. A monitoring body liberalization of civil aviation within the was to supervise and implement the decision, continent called for in the Yamoussoukro and an African air transport executing agency Decision of 1999 and the actions it needs to was to ensure fair competition. Even though take in the decade ahead to ensure that the the decision was a pan-African agreement benefi ts of liberalization are realized. to which most African states are bound, the parties decided that it should be implemented 11.1.1 The Yamoussoukro Decision by separate regional economic organizations. The monitoring body has met only a few Over the past three decades, much of the times. Competition rules and arbitration world has moved from a strictly regulated air procedures are still pending. A recent World transport industry to a more liberalized one. -

Report Afraa 2016

AAFRA_PrintAds_4_210x297mm_4C_marks.pdf 1 11/8/16 5:59 PM www.afraa.org Revenue Optimizer Optimizing Revenue Management Opportunities C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Learn how your airline can be empowered by Sabre Revenue Optimizer to optimize all LINES A ® IR SSO A MPAGNIE S AER CO IEN C N ES N I A D ES A N A T C IO F revenue streams, maximize market share I T R I I O R IA C C A I N F O N S E S A S A ANNUAL and improve analyst productivity. REPORT AFRAA 2016 www.sabreairlinesolutions.com/AFRAA_TRO ©2016 Sabre GLBL Inc. All rights reserved. 11/16 AAFRA_PrintAds_4_210x297mm_4C_marks.pdf 2 11/8/16 5:59 PM How can airlines unify their operations AFRAA Members AFRAA Partners and improve performance? American General Supplies, Inc. Simplify Integrate Go Mobile C Equatorial Congo Airlines LINKHAM M SERVICES PREMIUM SOLUTIONS TO THE TRAVEL, CARD & FINANCIAL SERVICE INDUSTRIES Y CM MY CY CMY K Media Partners www.sabreairlinesolutions.com/AFRAA_ConnectedAirline CABO VERDE AIRLINES A pleasurable way of flying. ©2016 Sabre GLBL Inc. All rights reserved. 11/16 LINES AS AIR SO N C A IA C T I I R O F N A AFRICAN AIRLINES ASSOCIATION ASSOCIATION DES COMPAGNIES AÉRIENNES AFRICAINES AFRAA AFRAA Executive Committee (EXC) Members 2016 AIR ZIMBABWE (UM) KENYA AIRWAYS (KQ) PRESIDENT OF AFRAA CHAIRMAN OF THE EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Captain Ripton Muzenda Mr. Mbuvi Ngunze Chief Executive Officer Group Managing Director and Chief Executive Officer Air Zimbabwe Kenya Airways AIR BURKINA (2J) EGYPTAIR (MS) ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES (ET) Mr. -

AFRAA Annual Report 2019

IRLINES ASS A PAGNIES O OM AERI C 20N S C EN 19 E N I A D ES A N A T C IO F I T R I I O R IA C C A I N F O N S E S A S A ANNUAL AFRAA REPORT Amadeus Airline Platform Bringing SIMPLICITY to airlines You can follow us on: AmadeusITGroup amadeus.com/airlineplatform AFRAA Executive Committee (EXC) Members 2019 AIR MAURITIUS (MK) RWANDAIR (WB) PRESIDENT OF AFRAA CHAIRPERSON OF THE EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Mr. Somas Appavou Ms. Yvonne Makolo Chief Executive Officer Chief Executive Officer CONGO AIRWAYS (8Z) KENYA AIRWAYS (KQ) CAMAIR-CO (QC) Mr. Desire Balazire Esono Mr. Sebastian Mikosz Mr. Louis Roger Njipendi Kouotou 1st Vice Chairman of the EXC 2nd Vice Chairman of the EXC Chief Executive Officer Chief Executive Officer Chief Executive Officer ROYAL AIR MAROC (AT) EGYPTAIR (MS) TUNISAIR (TU) Mr. Abdelhamid Addou Capt. Ahmed Adel Mr. Ilyes Mnakbi Chief Executive Officer Chairman & Chief Executive Officer Chief Executive Officer ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES (ET) AIR ZIMBABWE (UM) AIR NAMIBIA (SW) MAURITANIA AIRLINES (L6) Mr. Tewolde GebreMariam Mr. Joseph Makonise Mr. Xavier Masule Mrs. Amal Mint Maoulod Chief Executive Officer Chief Executive Officer Chief Executive Officer Chief Executive Officer ANNUAL REPORT 2019 I Foreword raffic growth in Africa has been consistently increasing since 2011. The demand for air passenger services remained strong in 2018 with a 6.9% year Ton year growth. Those good results were supported by the good global economic environment particularly in the first half of the year. Unlike passenger traffic, air freight demand recorded a very weak performance in 2018 compared to 2017. -

AIRLINES Monthly

AIRLINES monthly OTP APRIL 2018 Contents GLOBAL AIRLINES GLOBAL RANKING Top and bottom Regional airlines Latin American EMEA ASPAC North America and Caribbean Notes: % On-Time is percentage of flights that depart or Update: Status coverage as of April 2018 will only be based arrive within 15 minutes of schedule. on actual gate times rather than estimated times. This may Source: OAG flightview. Any reuse, publication or distribution of result in some airlines/airports being excluded from this report data must be attributed to OAG flightview. report. Global OTP rankings are assigned to all airlines/ Global OTP rankings are assigned to all Airports airports where OAG has status coverage for at least 80% where OAG has status coverage for at least 80% of the of scheduled flights. If you would like to review your flight scheduled flights. status feed with OAG please [email protected] AIRLINE MONTHLY OTP – APRIL 2018 Global airlines – top and bottom BOTTOM AIRLINE ON-TIME TOP AIRLINE ON-TIME FLIGHTS On-time performance On-time performance FLIGHTS Airline Arrivals Rank Flights Rank Airline Arrivals Rank Flights Rank TW T'way Air 99.5% 1 3,419 138 3H Air Inuit 39.2% 153 1,460 212 HX Hong Kong Airlines 95.8% 2 3,144 141 SF Tassili Airlines 41.9% 152 424 291 SATA International-Azores JH Fuji Dream Airlines 95.1% 3 2,122 173 S4 47.0% 151 625 268 Airlines S.A. PM Canaryfly 94.0% 4 1,072 232 EE Regional Jet 52.2% 150 70 367 BT Air Baltic Corporation 92.9% 5 4,624 117 VC ViaAir 53.4% 149 297 319 RC Atlantic Airways Faroe Islands 92.1% 6 221 333 TP TAP Air Portugal 53.8% 148 11,263 59 HR Hahn Air 91.7% 7 14 377 Z2 Philippines AirAsia Inc. -

Free Airlines a L Holm, R M Davis

i30 Tob Control: first published as 10.1136/tc.2003.005686 on 25 February 2004. Downloaded from RESEARCH PAPER Clearing the airways: advocacy and regulation for smoke- free airlines A L Holm, R M Davis ............................................................................................................................... Tobacco Control 2004;13(Suppl I):i30–i36. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.005686 Objective: To examine the advocacy and regulatory history surrounding bans on smoking in commercial airliners. Methods: Review of historical documents, popular press articles, and other sources to trace the timeline of events leading up to the US ban on smoking in airliners and subsequent efforts by airlines and other nations. Results: In early years, efforts by flight attendants and health advocates to make commercial airliners smoke-free were not productive. Advocacy efforts between 1969 and 1984 resulted in maintenance of the status quo, with modest exceptions (creation of smoking and non-smoking sections of aircraft, and a ban on cigar and pipe smoking). Several breakthrough events in the mid 1980s, however, led to an abrupt turnaround in regulatory efforts. The first watershed event was the publication in 1986 of the National Academy of Science’s report on the airliner cabin environment, which recommended banning smoking on all commercial flights. Subsequently, following concerted lobbying efforts by health advocates, Congress passed legislation banning smoking on US domestic flights of less than two hours, which became effective in 1988. The law was made permanent and extended to flights of less than six hours in 1990. This See end of article for landmark legislation propelled the adoption of similar rules internationally, both by airlines and their authors’ affiliations industry’s governing bodies. -

Uk Air Safety List Effective 1 January 2021

UK AIR SAFETY LIST EFFECTIVE 1 JANUARY 2021 LIST OF AIR CARRIERS WHICH ARE BANNED FROM OPERATING WITHIN THE UNITED KINGDOM. Name of the legal entity of Air Operator Certificate ICAO three State of the air carrier as indicated (‘AOC’) Number or Operating letter the on its AOC (and its Licence Number designator Operator trading name, if different) AVIOR AIRLINES ROI-RNR-011 ROI Venezuela BLUE WING AIRLINES SRBWA-01/2002 BWI Suriname IRAN ASEMAN AIRLINES FS-102 IRC Iran IRAQI AIRWAYS 001 IAW Iraq MED-VIEW AIRLINE MVA/AOC/10-12/05 MEV Nigeria AIR ZIMBABWE (PVT) 177/04 AZW Zimbabwe AFGHANISTAN Afghanistan All air carriers certified by the authorities with responsibility for regulatory oversight of Afghanistan, including ARIANA AFGHAN AIRLINES AOC 009 AFG Afghanistan KAM AIR AOC 001 KMF Afghanistan ANGOLA Angola All air carriers certified by the authorities with responsibility for regulatory oversight of, with the exception of TAAG Angola Airlines and Heli Malongo, including AEROJET AO-008/11-07/17 TEJ TEJ Angola GUICANGO AO-009/11-06/17 YYY Unknown Angola AIR JET AO-006/11-08/18 MBC MBC Angola BESTFLYA AIRCRAFT AO-015/15-06/17YYY Unknown Angola MANAGEMENT HELIANG AO 007/11-08/18 YYY Unknown Angola SJL AO-014/13-08/18YYY Unknown Angola SONAIR AO-002/11-08/17 SOR SOR Angola ARMENIA Armenia All air carriers certified by the authorities with responsibility for regulatory 1 oversight of Armenia, including AIRCOMPANY ARMENIA AM AOC 065 NGT Armenia ARMENIA AIRWAYS AM AOC 063 AMW Armenia ARMENIAN HELICOPTERS AM AOC 067 KAV Armenia ATLANTIS ARMENIAN -

Third Pan-African Aviation Coordination Conference

ICAO : THIRD PAN-AFRICAN AVIATION COORDINATION CONFERENCE CAPE TOWN INTERNATIONAL CONVENTION CENTRE, CAPE TOWN, SOUTH AFRICA 27 TO 29 JULY 2011 PANEL 1 : CREATION OF AN ASSOCIATION OF TRAINING ORGANIZATIONS THE AASA EXPERIENCE PRESENTATION BY : Chris Zweigenthal, Chief Executive, Airlines Association of Southern Africa 1 BRIEF • AASA EXPERIENCE : • Establishment and maintaining of • Legal • Organizational • Financial frameworks • Advancing interests of Airline Members • Cognizance of operational and financial conditions in Southern Africa • Lessons learnt to assist in establishment of establishment of Association for Training Organizations in Africa 2 AASA’S POSITION IN THE INDUSTRY • IATA (International Air Transport Association) The world body of membership for Airlines, taking the leadership role regarding strategy and airline development globally • REGIONAL ASSOCIATIONS are affiliated to IATA and support the objectives and initiatives of IATA while promoting the interests of their members and dealing with matters within their geographical regions and where necessary, globally. • Airlines Association of Southern Africa (AASA) : Regional Airline Association representing SADC based Airlines. 3 AASA’S POSITION IN THE INDUSTRY • AASA is one of 9 Regional Associations worldwide, with the others being : • Air Transport America (ATA), • Air Transport Association Canada (ATAC), • Association of European Airlines (AEA), • European Regional Airlines Association (ERA), • Association of Asia and Pacific Airlines (AAPA), • Arab Air Carriers Association -

List of Government-Owned and Privatized Airlines (Unofficial Preliminary Compilation)

List of Government-owned and Privatized Airlines (unofficial preliminary compilation) Governmental Governmental Governmental Total Governmental Ceased shares shares shares Area Country/Region Airline governmental Governmental shareholders Formed shares operations decreased decreased increased shares decreased (=0) (below 50%) (=/above 50%) or added AF Angola Angola Air Charter 100.00% 100% TAAG Angola Airlines 1987 AF Angola Sonair 100.00% 100% Sonangol State Corporation 1998 AF Angola TAAG Angola Airlines 100.00% 100% Government 1938 AF Botswana Air Botswana 100.00% 100% Government 1969 AF Burkina Faso Air Burkina 10.00% 10% Government 1967 2001 AF Burundi Air Burundi 100.00% 100% Government 1971 AF Cameroon Cameroon Airlines 96.43% 96.4% Government 1971 AF Cape Verde TACV Cabo Verde 100.00% 100% Government 1958 AF Chad Air Tchad 98.00% 98% Government 1966 2002 AF Chad Toumai Air Tchad 25.00% 25% Government 2004 AF Comoros Air Comores 100.00% 100% Government 1975 1998 AF Comoros Air Comores International 60.00% 60% Government 2004 AF Congo Lina Congo 66.00% 66% Government 1965 1999 AF Congo, Democratic Republic Air Zaire 80.00% 80% Government 1961 1995 AF Cofôte d'Ivoire Air Afrique 70.40% 70.4% 11 States (Cote d'Ivoire, Togo, Benin, Mali, Niger, 1961 2002 1994 Mauritania, Senegal, Central African Republic, Burkino Faso, Chad and Congo) AF Côte d'Ivoire Air Ivoire 23.60% 23.6% Government 1960 2001 2000 AF Djibouti Air Djibouti 62.50% 62.5% Government 1971 1991 AF Eritrea Eritrean Airlines 100.00% 100% Government 1991 AF Ethiopia Ethiopian -

Ben Guttery Collection History of Aviation Collection African Airlines Box 1 ADC – Nigeria Aero Contractors Aeromaritime Aerom

Ben Guttery Collection History of Aviation Collection African Airlines Box 1 ADC – Nigeria Aero Contractors Aeromaritime Aeromas African Intl Air Afrique #1 Air Afrique #2 Air Algerie Air Atlas Air Austral Air Botswana Air Brousse Air Cameroon Air Cape Air Carriers Air Djibouti Air Centrafique Air Comores Air Congo Air Gabon Air Gambia Air Ivoire Air Kenya Aviation Airlink Air Lowveld Air Madagascar Air Mahe Air Malawi Air Mali Air Mauritanie Air Mauritius Air Namibia Box 2 Air Rhodesia Air Senegal Air Seychelles Air Tanzania Air Zaire Air Zimbabwe Aircraft Operating Co. Alliances Avex Avia Bechuanaland Natl. Bellview Bop Air Cameroon Airlines Campling Bros. Capital Air Caspair / Caspar Cata Catalina Safari Central African Airways Christowitz Clairways Command Airways Commercial Air Service Copperbelt Court Heli DAS – Dairo Desert Airways Deta DTA Angola East African Airways Corp Eastern Air Zambia Egypt Air Elders Colonial Box 3 Ethiopian Federal Airlines Sudan Flite Star Gambia Airways German Ghana Airways Guinea Hold – Trade Hunting Clan Imperial Inter Air International Air Kitale Zaire Katanga Kenya Airways Lam Lara Leopard Air Lana Lesotho Airways Liverian National Libyan Arab Magnum MISR Namib Air National Nigeria Airways North African Airlines (Tunisia) Phoenix Protea Pyramid RAC – Rhodesia Regie Malgache R.A.N.A Rhodesian Air Service Box 4 Rossair Royal Air Maroc Royal Swazi Ruac Sa Express Safair Safari Air Svcs Saide Sata Algeria SATT Scibe Shorouk Sierra Leone Airlines Skyways Sobelair South African Aerial Transport Somali Airlines -

Travelsky Interline Traffic Agreement

TravelSky Interline Traffic Agreement List of airlines issuable on HR-169 ticket. IATA IATA IATA Code Airline Name Code Airline Name Code Airline Name 0B Blue Air Airline BI Royal Brunei IZ Arkia 2M Maya Island Air BL Jetstar Pacific Airlines J2 Azerbaijan Airlines 3K Jetstar Asia BP Air Botswana JD Beijing Capital Airlines 3M Silver Airways Corp BR EVA Air JJ TAM Linhas Aereas 3S Air Antilles Express BT Air Baltic JL Japan Airlines 3U Sichuan Airlines BV Blue Panorama Airlines JQ Jetstar 4O Interjet BW Caribbean Airlines JU Air Serbia 5F FlyOne CG Airlines PNG JX Starlux Airlines 5H Five Forty Aviation CI China Airlines JY Intercaribbean Airways 5U TAG - Transportes Aereos Guate... CM Copa Airlines K6 Cambodia Angkor Air 7C Jeju Air CU Cubana de Aviacion K7 Air KBZ 7R Rusline CX Cathay Pacific KA Cathay Dragon 8L Lucky Air DE Condor KC Air Astana 8M Myanmar Airways DV JSC Aircompany Scat KE Korean Air 8Q Onur Air DZ Donghai Airlines KF Air Belgium 8U Afriqiyah Airways EI Aer Lingus KM Air Malta 9K Cape Air EK Emirates KP Asky 9N Tropic Air Limited EL Ellinair KQ Kenya Airways 9U Air Moldova EN Air Dolomiti KR Cambodia Airways 9V Avior ET Ethiopian Airlines KU Kuwait Airways 9X Southern Airways Express EY Etihad Airways KX Cayman Airways A3 Aegean Airlines FB Bulgaria Air LA Lan Airlines A9 Georgian Airways FI Icelandair LG Luxair AC Air Canada FJ Fiji Airways LH Lufthansa AD Azul Linhas Aereas Brasileiras FM Shanghai Airlines LI LIAT AE Mandarin Airlines GA Garuda Indonesia LM Loganair AH Air Algerie GF Gulf Air LO LOT Polish Airlines