Philosophy of Science Association

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Utilitarianism & the Afterlife

Utilitarianism & the Afterlife The paradox of a pleasant hereafter Betsy McCall The goal of Utilitarianism is to lay out a moral philosophy to provide us a way of living, and a way of making difficult moral choices correctly(Mill, 2001) in circumstances which are uncommon enough that experience has not, or cannot, prepare us for the solution. But in doing so, Utilitarianism must confront the same moral challenges confronted by all moral philosophies, including the consequences of belief in the afterlife(Hasker, 2005). The afterlife has provided a complex moral challenge for many moral philosophical frameworks throughout the ages, from Buddhism to Christianity. Buddhism posits that life is suffering, and that the ultimate goal of living is really to escape living altogether by achieving nirvana, or at least, a better life in the next reincarnation(Becker, 1993). Christianity similarly puts this life into a comparison with another better alternative, in this case, the possibility of an infinitely better afterlife in heaven with god and the angels(Pohle, 1920). In both cases, the philosophical frameworks have been forced to incorporate specific prohibitions against suicide in order to avoid the apparently logical conclusion that death is preferable to life, and we would do well to get ourselves there as quickly as possible. Mill, in arguing for Utilitarianism, does not specifically address this question, perhaps because Mill himself gave the afterlife little personal credence(Wilson, 2009). However, writing to a largely Christian Western audience, like Christianity, and a deep-seated historical affinity for belief in reincarnation(Haraldsson, 2005), Mill and his followers must be prepared to address this potential concern. -

Foundations of Nursing Science 9781284041347 CH01.Indd Page 2 10/23/13 10:44 AM Ff-446 /207/JB00090/Work/Indd

9781284041347_CH01.indd Page 1 10/23/13 10:44 AM ff-446 /207/JB00090/work/indd © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC. NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION PART 1 Foundations of Nursing Science 9781284041347_CH01.indd Page 2 10/23/13 10:44 AM ff-446 /207/JB00090/work/indd © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC. NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION 9781284041347_CH01.indd Page 3 10/23/13 10:44 AM ff-446 /207/JB00090/work/indd © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC. NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION CHAPTER Philosophy of Science: An Introduction 1 E. Carol Polifroni Introduction A philosophy of science is a perspective—a lens, a way one views the world, and, in the case of advanced practice nurses, the viewpoint the nurse acts from in every encounter with a patient, family, or group. A person’s philosophy of science cre- ates the frame on a picture—a message that becomes a paradigm and a point of reference. Each individual’s philosophy of science will permit some things to be seen and cause others to be blocked. It allows people to be open to some thoughts and potentially keeps them closed to others. A philosophy will deem some ideas correct, others inconsistent, and some simply wrong. While philosophy of sci- ence is not meant to be viewed as a black or white proposition, it does provide perspectives that include some ideas and thoughts and, therefore, it must neces- sarily exclude others. The important key is to ensure that the ideas and thoughts within a given philosophy remain consistent with one another, rather than being in opposition. -

The Synchronicity of Hope and Enhanced Quality of Life in Terminal Cancer

University of Central Florida STARS Honors Undergraduate Theses UCF Theses and Dissertations 2016 The Synchronicity of Hope and Enhanced Quality of Life in Terminal Cancer Brianna M. Terry University of Central Florida Part of the Nursing Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the UCF Theses and Dissertations at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Terry, Brianna M., "The Synchronicity of Hope and Enhanced Quality of Life in Terminal Cancer" (2016). Honors Undergraduate Theses. 75. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses/75 THE SYNCHRONICITY OF HOPE AND ENHANCED QUALITY OF LIFE IN TERMINAL CANCER by BRIANNA TERRY A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors in the Major Program in Nursing in the College of Nursing and in the Burnett Honors College at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer Term, 2016 Thesis Chair: Dr. Susan Chase Abstract Cancer is the second leading cause of death in the United States and a leading cause of death worldwide. The rate of mortality is currently approximately 171.2 out of every 100,000 individuals with a terminal cancer diagnosis annually. Individuals with terminal cancer diagnoses facing probable mortality utilize various coping mechanisms or internal resources in an attempt to maintain an internal sense of well-being, commonly referred to as quality of life (QOL). -

1 Bringing Real Realism Back Home: a Perspectival Slant Michela Massimi

Bringing real realism back home: a perspectival slant Michela Massimi School of Philosophy, Psychology, and Language Sciences University of Edinburgh [email protected] 1. Introduction When it comes to debates on realism in science, Philip Kitcher’s Real Realism: The Galilean Strategy (henceforth abbreviated as RR) occupies its well-deserved place among my top five must-read articles published in the past forty years or so on the topic (alongside Putnam’s What is realism?; Boyd’s Realism, anti-foundationalism and the enthusiasm for Natural Kinds; Laudan’s A refutation of convergent realism; and Psillos’ The present state of the scientific realism debate). Personal as this top-five list may be, there is no doubt that Real Realism has ushered in a silent revolution. Without much fanfare, it has shown how realism is hard to resist because it “begins at home” and “it never ventures into the metaphysical never-never- lands to which antirealists are so keen to banish their opponents” (RR, p. 191). Kitcher has taught us how realism began with homely considerations such as those used by Galileo to persuade the Venetians about the reliability of his telescope to spot ships approaching the harbor. The following step from ‘being a reliable naval instrument’ to ‘being a reliable instrument, in general’—capable of revealing the craters of the Moon, the satellites of Jupiter, and the phases of Venus—was a short one. The Galilean strategy that Kitcher has so admirably defended in Real Realism against both empiricism and constructivism (in their respective semantic and epistemic forms) entice us to a “homely line of thought”, and warns us against any “Grand Metaphysical Conclusions”. -

Developing the Researchable Problem

© Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION CHAPTER © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett2 Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION Developing the © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTIONResearchableNOT Problem FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © echo3005/ShutterStock, Inc. © echo3005/ShutterStock, © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION Objectives © Jones & BartlettUpon completion Learning, of thisLLC chapter, the reader should© Jonesbe prepared & Bartlett to: Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE 1.OR Discuss DISTRIBUTION the elements needed to formulateNOT aFOR research SALE ques- OR DISTRIBUTION tion, specifi cally discussing the PICOT process of developing a research question. 2. Utilize sample scenarios to formulate suitable research questions. © Jones & Bartlett Learning, 3.LLC Discuss the development© of Jones a testable & hypothesis.Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION4. Describe the diff erent categoriesNOT FOR of hypotheses:SALE OR research DISTRIBUTION vs. sta- tistical, directional vs. nondirectional. 5. Determine when it would be most appropriate to utilize a research question and when it would be most appropriate to uti- © Joneslize a& hypothesis. Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT6. FORDiscuss SALE the diff OR erence DISTRIBUTION between a directional hypothesisNOT and FORa SALE OR DISTRIBUTION nondirectional hypothesis. 7. Discuss the diff erence between a research hypothesis and a sta- tistical hypothesis. © Jones & Bartlett8. -

Levitt Sample.Qxd

CHAPTER 1 Psychological Research The Whys and Hows of the Scientific Method CONSIDER THE FOLLOWING QUESTIONS AS YOU READ CHAPTER 1 • Why do psychologists use the scientific method? • How do psychologists use the scientific method? • What are the canons of the scientific method? • What is the difference between basic and applied research? • How do basic and applied research interact to increase our knowledge about behavior? As an instructor of an introductory psychology course for psychology majors, I ask my first-semester freshman students the question “What is a psychologist?” At the beginning of the semester, students typically say that a psychologist listens to other people’s problems to help them live happier lives. By the end of the semester and their first college course in psychology, these same students will respond that a psychologist studies behavior through research. These students have learned that psychology is a science that investigates behav - ior, mental processes, and their causes. That is what this book is about: how psychologists use the scientific method to observe and understand behavior and mental processes. The goal of this text is to give you a step-by-step approach to designing research in psy - chology, from the purpose of research (discussed in this chapter) and the types of questions psychologists ask about behavior, to the methods psychologists use to observe and under - stand behavior and describe their findings to others in the field. WHY PSYCHOLOGISTS CONDUCT RESEARCH Think about how you know the things you know. How do you know the earth is round? How do you know it is September? How do you know that there is a poverty crisis in some parts of Africa? There are probably many ways that you know these things. -

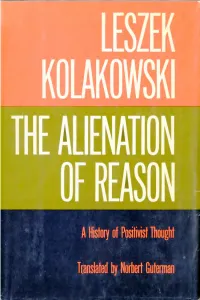

The Alienation of Reason a HISTORY of POSITIVIST THOUGHT .,....O by Leszek Kolakowski

The Alienation of Reason A HISTORY OF POSITIVIST THOUGHT .,....o by Leszek Kolakowski Translated by Norbert Guterman DOUBLEOAY a COMPANY, INC. GARDEN CITY, NEW YORK 1968 Contents Preface V ONE. An Over-all View of Positivism TWO. Positivism Down to David Hume II THREE. Auguste Comte: Positivism in the Romantic Age 47 FOUR. Positivism Triumphant 73 FIVE. Positivism at the Turn of the Ccntury 104 SIX. Conventionalism-Destruction of the Concept of Fact 134 SEVEN. Pragmatism and Positivism 154 EIGHT. Logical Empiricism: A Scientistic Defense of Threatened Gvilization 174 Conclusion 207 Index 221 8 nIE ALIENATION Oll' REASON sense, i.e„ to the cxtent that they teil us what opcrations arc or arc not effcctive in achicving a desircd end. Examplcs of such tcchnical judgmcnts would bc a statement to thc cff cct that we should administer pcnicillin in a case of pncumonia or one to the cffect that children ought not be threatened with a bcating if they won't cat. Such statements can, clearly, be justificd, if thcir mcaning is respectivcly that pcnicillin is an cffectivc rem cdy against pncumonia, and that thrcatcning children with pun ishmcnt to makc them cat causes charactcrological handicaps. And if wc assume tacitly that, as a rulc, it is a good thing to eure the sick and a bad thing to inflict psychic dcformation upon childrcn, the above-mcntioncd statements can be justi.fied, even though thcy do havc thc form of normative judgmcnts. But we are not to assume that any valuc assertion that we rccognizc as truc ''in itsclf," rathcr than in rclation to something eise, can bc justificd by expericnce. -

Improving the Testability of Object-Oriented Software During Testing and Debugging Processes

International Journal of Computer Applications (0975 – 8887) Volume 35– No.11, December 2011 Improving the Testability of Object-oriented Software during Testing and Debugging Processes Sujata Khatri R.S. Chhillar V.B.Singh DDU College DCSA, M.D.U Delhi College of Arts & University of Delhi, Delhi Rohtak, Haryana Commerce India India University of Delhi, Delhi India ABSTRACT procedural and object oriented software system. Software reliability growth models which is used for finding failure Testability is the probability whether tests will detect a fault, distribution and fault complexity of software is described in given that a fault in the program exists. How efficiently the section 2. Section 3 describes Data Sets along with sample of faults will be uncovered depends upon the testability of the software. Various researchers have proposed qualitative and bug reported data. failure . The impact of value of parameter quantitative techniques to improve and measure the testability of reliability growth models on improving testability is of software. In literature, a plethora of reliability growth described in section 4. Conclusion of the paper and future models have been used to assess and measure the quantitative research direction is given in section 5. quality assessment of software during testing and operational phase. The knowledge about failure distribution and their 1.1 Testability of Software complexity can improve the testability of software. Testing effort allocation can be made easy by knowing the failure The IEEE Standard Glossary of Software Engineering distribution and complexity of faults, and this will ease the Terminology‟ defines testability as“(1) the degree to which a process of revealing faults from the software. -

Testability of Object-Oriented Systems: a Metrics-Based Approach

Testability of Object-Oriented Systems: a Metrics-based Approach Magiel Bruntink ii °c 2003 Magiel Bruntink Cover image `Uzumaki' °c 2003 Akiyoshi Kitaoka, used with permission. `U' means rabbits, `zu' means ¯gure, `maki' means rotation, and `Uzumaki' means spirals or swirls. Yellow represents the color of the moon in Japan and it is imagined (though not seriously) that rabbits live in the moon and make mochi (food made from rice). Akiyoshi Kitaoka describing the meaning of `Uzumaki' on his web site. The drawing appeared in his Japanese book Trick Eyes 2, and quickly became popular on the Internet. This work has been typeset using Leslie Lamport's LATEX, in Donald Knuth's Computer Modern Roman font, 11 pt. Testability of Object-Oriented Systems: a Metrics-based Approach Magiel Bruntink September 2003 Master's Thesis Universiteit van Amsterdam Faculteit der Natuurwetenschappen, Wiskunde en Informatica Sectie: Programmatuur Afstudeerdocent: Prof. dr. Paul Klint Begeleiders: Dr. Arie van Deursen & Dr. Tobias Kuipers ii Preface When I ¯rst saw the `Uzumaki' drawing, it struck me how well it captured my state of mind at the beginning of the work on this thesis. The topic I had chosen to explore appeared to be huge and very di±cult, and many things of interest were scattered throughout it. I was unsure where to focus my attention. One cannot help but feel the same way when looking at `Uzu- maki'; wherever one looks, there is always something going on in another part of the drawing. Hence I decided to put `Uzumaki' on the cover of my thesis. However, the analogy does not stop there. -

Testability and Meaning Author(S): Rudolf Carnap Reviewed Work(S): Source: Philosophy of Science, Vol

Testability and Meaning Author(s): Rudolf Carnap Reviewed work(s): Source: Philosophy of Science, Vol. 3, No. 4 (Oct., 1936), pp. 419-471 Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Philosophy of Science Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/184400 . Accessed: 04/08/2012 12:19 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press and Philosophy of Science Association are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Philosophy of Science. http://www.jstor.org philosophiof Science VOL. 3 October, 1936 NO. 4 Testability and Meaning BY RUDOLF CARNAP I. INTRODUCTION I. Our Problem: Confirmation,Testing and Meaning.......... 420 2. The Older Requirement of Verifiability ..................... 42I 3. Confirmation instead of Verification ........................ 425 4. The Material and the Formal Idioms........ ............... 427 II. LOGICAL ANALYSIS OF CONFIRMATION AND TESTING 5. Some Terms and Symbols of Logic ......................... 43I 6. Reducibility of Confirmation .............................. 434 7. D efinitions.............................................. 439 8. Reduction Sentences ..................................... 441 9. Introductive Chains...................................... 444 10. Reduction and Definition................................. 448 III. EMPIRICAL ANALYSIS OF CONFIRMATION AND TESTING I I. Observable and Realizable Predicates ...................... 454 12. Confirmability ..................................... .... 456 I3. -

Four Examples of Pseudoscience

Four Examples of Pseudoscience Marcos Villavicencio Tenerife, Canarias, Spain E-mail address: [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-6700-4872 January 2020 Abstract A relevant issue in the philosophy of science is the demarcation problem: how to distinguish science from nonscience, and, more specifically, science from pseudoscience. Sometimes, the demarcation problem is debated from a very general perspective, proposing demarcation criteria to separate science from pseudoscience, but without discussing any specific field in detail. This article aims to focus the demarcation problem on particular disciplines or theories. After considering a set of demarcation criteria, four pseudosciences are examined: psychoanalysis, speculative evolutionary psychology, universal grammar, and string theory. It is concluded that these theoretical frameworks do not meet the requirements to be considered genuinely scientific. Keywords Demarcation Problem · Pseudoscience · Psychoanalysis · Evolutionary psychology · Universal grammar · String theory 1 Introduction The demarcation problem is the issue of how to differentiate science from nonscience in general and pseudoscience in particular. Even though expressions such as “demarcation problem” or “pseudoscience” were still not used, some consider that an early interest for demarcation existed as far back as the time of ancient Greece, when Aristotle separated episteme (scientific knowledge) from mere doxa (opinion), holding that apodictic certainty is the basis of science (Laudan 1983, p. 112). Nowadays, the issue of demarcation continues being discussed. Certainly, demarcating science from pseudoscience is not a topic of exclusive philosophical interest. Scientists and members of skeptical organizations such as the Committee for Scientific Inquiry also deal with this crucial theme. The issue of how to recognize pseudoscience not only affects academia. -

Elliott Sober Source: Proceedings and Addresses of the American Philosophical Association, Vol

Testability Author(s): Elliott Sober Source: Proceedings and Addresses of the American Philosophical Association, Vol. 73, No. 2 (Nov., 1999), pp. 47-76 Published by: American Philosophical Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3131087 Accessed: 02/09/2008 14:56 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=amphilosophical. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org TESTABILITY ElliottSober, University of Wisconsin Givenas PresidentialAddress to the CentralDivision of the AmericanPhilosophicalAssociation in New Orleans,May 1999. I Thatsome propositionsare testable,while othersare not, was a funda- mentalidea in the philosophicalprogram known as logicalempiricism.