Foreign Countries (1942-1943)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jews on Route to Palestine 1934-1944. Sketches from the History of Aliyah

JEWS ON ROUTE TO PALESTINE 1934−1944 JAGIELLONIAN STUDIES IN HISTORY Editor in chief Jan Jacek Bruski Vol. 1 Artur Patek JEWS ON ROUTE TO PALESTINE 1934−1944 Sketches from the History of Aliyah Bet – Clandestine Jewish Immigration Jagiellonian University Press Th e publication of this volume was fi nanced by the Jagiellonian University in Krakow – Faculty of History REVIEWER Prof. Tomasz Gąsowski SERIES COVER LAYOUT Jan Jacek Bruski COVER DESIGN Agnieszka Winciorek Cover photography: Departure of Jews from Warsaw to Palestine, Railway Station, Warsaw 1937 [Courtesy of National Digital Archives (Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe) in Warsaw] Th is volume is an English version of a book originally published in Polish by the Avalon, publishing house in Krakow (Żydzi w drodze do Palestyny 1934–1944. Szkice z dziejów alji bet, nielegalnej imigracji żydowskiej, Krakow 2009) Translated from the Polish by Guy Russel Torr and Timothy Williams © Copyright by Artur Patek & Jagiellonian University Press First edition, Krakow 2012 All rights reserved No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any eletronic, mechanical, or other means, now know or hereaft er invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers ISBN 978-83-233-3390-6 ISSN 2299-758X www.wuj.pl Jagiellonian University Press Editorial Offi ces: Michałowskiego St. 9/2, 31-126 Krakow Phone: +48 12 631 18 81, +48 12 631 18 82, Fax: +48 12 631 18 83 Distribution: Phone: +48 12 631 01 97, Fax: +48 12 631 01 98 Cell Phone: + 48 506 006 674, e-mail: [email protected] Bank: PEKAO SA, IBAN PL80 1240 4722 1111 0000 4856 3325 Contents Th e most important abbreviations and acronyms ........................................ -

Krigen Mot Ryssarna I Vin Också En Utmarkelse Av Den Fin Det Er Imidlertid Tre Artikler Om Program.» Kultur

Stiftelsen norsk Okkupasjonshistorie, 2014 UAVHENGIG AVIS Nr.6 - 1992 - 41. årgang Finsk godgjøreIse KULTUR ER BASISVARE, til utenlandske IKHESTORMARKEDPRODUKT Jeg har skummet dagens A v Frederik Skaubo med overskrift: Rambo eller krigsdeltagere Morgenblad og bl.a. merket Rimbaud? hvor han angriper Efter 50 år får de svenska sol ersattning på knappt 1.500 kro meg datoen, 8. mai, som jo så selv om avskaffelse av familien det syn at staten (myndighe dater som frivilligt hjiilpte Fin nor får alla frivillige utlanningar absolutt gir grunn til ettertanke. var oppført på kommunistenes tene) også har noe ansvar for land i krigen mot ryssarna i vin också en utmarkelse av den fin Det er imidlertid tre artikler om program.» kultur. Han er såvisst ikke opp ter och fortsattningskriget 1939- ska staten. Ersattningen ar mera et annet viktig emne, jeg her fes Et fenomen idag er f.eks. at tatt av kultur som identitets 45 ekonomisk ersattning. en symbolisk gest av Finland tet meg ved. Hver for seg avkla mens Høyre med pondus pro fremmende, tradisjonsbevaren Det var i samband med det som i år firar sitt 75-års jubi rende, tildels avslørende i for klamerer en politikk bygget på de, kvalitetsskapende og estetisk årliga firandet av veterandagen i leum. bindelse med vårt kultursyn. De «det kristne verdigrunnlag ... og etisk oppdragende. Nesten Finland som regeringen fattade Framfor allt fOr de ester som er dessuten aktuelle også når vil forholdet for de flestes ved mer anarkistisk enn liberal går beslut om att hedra de 5.000 frivilligt deltog i striderna på denne avis kommer ut. -

Nasjonal Samlings Ideologiske Utvikling 1933- 1937

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NORA - Norwegian Open Research Archives “Ja takk, begge deler” - en analyse av Nasjonal Samlings ideologiske utvikling 1933- 1937 Robin Sande Masteroppgave Institutt for statsvitenskap UNIVERSITETET I OSLO 12. desember 2008 1 Forord Arbeidet med denne oppgaven tok til i mars 2008. Ideen fikk jeg imidlertid under et utvekslingsopphold i Berlin vinteren 2007/08. Fagene ”Politische Theorie und Geschichte am Beispiel der Weimarer Republik” og ”Politische Philosophien im Kontext des Nationalsozialismus” gjorde meg oppmerksom på at Nasjonal Samling må ha vært noe mer enn bare vertskap for tyske invasjonsstyrker. Hans Fredrik Dahls eminente biografi om Quisling: En fører blir til, vekket interessen ytterligere. Oppgaven kunne selvfølgelig vært mye mer omfattende. Det foreligger uendelige mengder litteratur både om liberalistisk elitisme og spesielt fascisme. Nasjonal Samlings historie kunne også vært behandlet mye mer inngående dersom jeg hadde hatt tid til et mer omfattende kildesøk. Dette gjelder også persongalleriet i Nasjonal Samling som absolutt hadde fortjent både mer tid og plass. Fremtredende personer som Johan B.Hjorth, Halldis Neegård Østbye, Gulbrand Lunde og Hans S.Jacobsen kunne hver for seg utgjort en masteravhandling alene. En videre diskusjon av de dominerende ideologiske tendensene i Nasjonal Samling kunne også vært meget intressant. Hvordan fortsatte den ideologiske utviklingen etter 1937 og frem til krigen, og hvordan fremsto Nasjonal Samling ideologisk etter den tyske invasjonen? Desverre er dette spørsmål som jeg, eller noen andre, må ha til gode. For å levere oppgaven på normert tid har det vært nødvendig å begrense omfanget av oppgaven. -

Guides to German Records Microfilmed at Alexandria, Va

GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA. No. 32. Records of the Reich Leader of the SS and Chief of the German Police (Part I) The National Archives National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration Washington: 1961 This finding aid has been prepared by the National Archives as part of its program of facilitating the use of records in its custody. The microfilm described in this guide may be consulted at the National Archives, where it is identified as RG 242, Microfilm Publication T175. To order microfilm, write to the Publications Sales Branch (NEPS), National Archives and Records Service (GSA), Washington, DC 20408. Some of the papers reproduced on the microfilm referred to in this and other guides of the same series may have been of private origin. The fact of their seizure is not believed to divest their original owners of any literary property rights in them. Anyone, therefore, who publishes them in whole or in part without permission of their authors may be held liable for infringement of such literary property rights. Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 58-9982 AMERICA! HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION COMMITTEE fOR THE STUDY OP WAR DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECOBDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXAM)RIA, VA. No* 32» Records of the Reich Leader of the SS aad Chief of the German Police (HeiehsMhrer SS und Chef der Deutschen Polizei) 1) THE AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION (AHA) COMMITTEE FOR THE STUDY OF WAE DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA* This is part of a series of Guides prepared -

Tyranny Could Not Quell Them

ONE SHILLING , By Gene Sharp WITH 28 ILLUSTRATIONS , INCLUDING PRISON CAM ORIGINAL p DRAWINGS This pamphlet is issued by FOREWORD The Publications Committee of by Sigrid Lund ENE SHARP'S Peace News articles about the teachers' resistance in Norway are correct and G well-balanced, not exaggerating the heroism of the people involved, but showing them as quite human, and sometimes very uncertain in their reactions. They also give a right picture of the fact that the Norwegians were not pacifists and did not act out of a sure con viction about the way they had to go. Things hap pened in the way that they did because no other wa_v was open. On the other hand, when people acted, they The International Pacifist Weekly were steadfast and certain. Editorial and Publishing office: The fact that Quisling himself publicly stated that 3 Blackstock Road, London, N.4. the teachers' action had destroyed his plans is true, Tel: STAmford Hill 2262 and meant very much for further moves in the same Distribution office for U.S.A.: direction afterwards. 20 S. Twelfth Street, Philadelphia 7, Pa. The action of the parents, only briefly mentioned in this pamphlet, had a very important influence. It IF YOU BELIEVE IN reached almost every home in the country and every FREEDOM, JUSTICE one reacted spontaneously to it. AND PEACE INTRODUCTION you should regularly HE Norwegian teachers' resistance is one of the read this stimulating most widely known incidents of the Nazi occu paper T pation of Norway. There is much tender feeling concerning it, not because it shows outstanding heroism Special postal ofler or particularly dramatic event§, but because it shows to new reuders what happens where a section of ordinary citizens, very few of whom aspire to be heroes or pioneers of 8 ~e~~ 2s . -

Shirt Movements in Interwar Europe: a Totalitarian Fashion

Ler História | 72 | 2018 | pp. 151-173 SHIRT MOVEMENTS IN INTERWAR EUROPE: A TOTALITARIAN FASHION Juan Francisco Fuentes 151 Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Spain [email protected] The article deals with a typical phenomenon of the interwar period: the proliferation of socio-political movements expressing their “mood” and identity via a paramilitary uniform mainly composed of a coloured shirt. The analysis of 34 European shirt movements reveals some common features in terms of colour, ideology and chronology. Most of them were consistent with the logic and imagery of interwar totalitarianisms, which emerged as an alleged alternative to the decaying bourgeois society and its main political creation: the Parliamentary system. Unlike liBeral pluralism and its institutional expression, shirt move- ments embody the idea of a homogeneous community, based on a racial, social or cultural identity, and defend the streets, not the Ballot Boxes, as a new source of legitimacy. They perfectly mirror the overwhelming presence of the “brutalization of politics” (Mosse) and “senso-propaganda” (Chakhotin) in interwar Europe. Keywords: fascism, Nazism, totalitarianism, shirt movements, interwar period. Resumo (PT) no final do artigo. Résumé (FR) en fin d’article. “Of all items of clothing, shirts are the most important from a politi- cal point of view”, Eugenio Xammar, Berlin correspondent of the Spanish newspaper Ahora, wrote in 1932 (2005b, 74). The ability of the body and clothing to sublimate, to conceal or to express the intentions of a political actor was by no means a discovery of interwar totalitarianisms. Antoine de Baecque studied the political dimension of the body as metaphor in eighteenth-century France, paying special attention to the three specific func- tions that it played in the transition from the Ancien Régime to revolutionary France: embodying the state, narrating history and peopling ceremonies. -

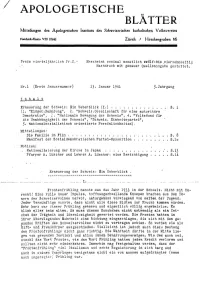

Jg 05 Heft 01 Datum 19410113.Pdf

APOLOGETISCHE BLÄTTER Mitteilungen des Apologetischen Instituts des Schweizerischen katholischen Volksvereins Pottdiedc-Konto vni 27842 Zürich / Hirschengraben 86 ■Preis vierteljährlich Fr»2, Erscheint zweimal monatlich zwölfbis vierzehnseitig Nachdruck mit genauer Quellenangabe gestattet. Nr.l (Erste Januarnummer) 13« Januar 1941 5.Jahrgang Inhalt Erneuerung der Schweiz: Ein Ueberblick (i.) S. 1 (1. "Eidgen.Sammlung", 2. "Schweiz.Gesellschaft für eine autoritäre Demokratie", I. "Nationale Bewegung der Schweiz", 4. "Volksb'und für die Unabhängigkeit der Schweiz", "Schweiz. Einheitspartei", 5. nationalsozialistisch orientierte Persönlichkeiten)• Mitteilungen: Die Familie im Film . S , 8 Manifest der Sozialdemokratischen ParteiOpposition .......... S lo Notizen: . Nationalisierung der Kirche in Japan 13 PfarrerA. Lüscher und Lehrer A. Lüscher: eine Berichtigung .14 Erneuerung der Schweiz: Ein Ueberblick I... Frontenfrühling nannte man das Jahr 1933 in der Schweiz. Nicht mit Un rechte Eine Fülle neuer Impulse, hoffnungschwellende Knospen brachen aus dem In nern des Schweizervolkes hervor, naturgemäss vorwiegend von Seiten der Jugend. Jeder Vernünftige wusste, dass nicht alle diese Blüten zur Frucht kommen würden. Sehr kurz war dieser Frühling gewesen und eigentlich völlig ergebnislos. Es blieb alles beim alten. Es muss dieses Geschehen nicht notwendig als ein Zei chen 'der Trägheit und Ideenlosigkeit gewertet werden. Die Fronten hatten in ihrer überwiegenden Mehrheit eine Richtung eingeschlagen, die sich mit den ge sunden "Kräften -

Interview with Joseph Roos, Los Angeles, July 20, 194J Mr. Roos Is

Interview with Joseph Roos, Los Angeles, July 20, 194J Mr. Roos is *iitiiaia&xi a memb r of a large Jewish law firm which operates a news research service at 727 W 7th St* The firm is connected withe the anti-defamation league whose object is to expose anti-semitic propaganda. In 1940 the research service published two of thier weekly news letters on Japan se activities. These were concerned with alleged milit ry preparation of Japan in coll boration with Germany and are most interesting because they were reprinted, word for word, in Martin Dies yellow Book as the product f Dies own investiagtion. Later HXHKXXiHH MarcantAnio photostated the News Letters in an effort to discredit the Dies Committee. Mr. Roos knew very little about the evacuation problems but he directed me to other people in the city. Later, also, Mxxthe senior member of the firm (a rominent Legionaire and layyer) Leon Lewis called me. I was unable to see ir. L becau e ixxxxof my overcrowded schedule, but ho told me he had definitive proof on h nd tj refute the story that Jewish business men rofited from the evacuati n. If and when we ever get an economist to do some work onthe Japanese problem, Mr. L will be of great aid. He said he w uld turn over hi oo plete file to the Study. NEW LETTER Published by News Research Service, Inc., 727 W. Seventh Street, Los Angeles, Catifornia S(MM< of *in'!. Moří ú M .fri.iu StudfnU and W,it*ri. F ) ^ u r t . -

Bestand Hirschengraben 62 8092 Zürich +41 44 632 40 03 [email protected]

ETH Zürich Archiv für Zeitgeschichte Bestand Hirschengraben 62 8092 Zürich +41 44 632 40 03 [email protected] Nachlässe und Einzelbestände / F-M / Henne, Rolf Henne, Rolf f1ad1588-59a8-481a-984b-ce5093d622fd Identifikation Bestandssignatur NL Rolf Henne Kurztitel Henne, Rolf AfZ Online Archives Henne, Rolf Bestandsname Nachlass Dr. iur. Rolf Henne (1901-1966) Entstehungszeit 1914 - 1966 Umfang 3.45 Laufmeter Kontext Provenienz Henne, Rolf Geschichte / Biografie Henne, Rolf 7.10.1901-22.7.1966 Dr. iur. Geb. in Schaffhausen (amtliche Vornamen: Hugo Rudolf), reformiert, von Sargans und Schaffhausen, Sohn des Hugo, Arztes, und der Gertrud geb. Bendel, Urenkel von Josef Anton Henne (1798-1870); 1939 Heirat mit Ursula Weilenmann. Medizinstudium bis zum 1. Propädeutikum; Studium der Rechtswissenschaften in Zürich und Heidelberg, 1927 Promotion. Mitglied der Freisinnigen Partei. 1930-1934 Mitarbeit im Advokaturbüro des Schaffhauser FDP-Ständerats Heinrich Bolli. Ab 1931/32 Betätigung in der Neuen Front; 1932 Gründung der Ortsgruppe Schaffhausen; 1933 Austritt aus der Freisinnigen Partei; 1933/34 Schaffhauser "Gauführer" der Neuen Front, die sich 1933 mit der Nationalen Front zusammenschloss. Im Herbst 1933 erhielt Henne bei der Ständeratsersatzwahl 27% der Stimmen. 1934-1938 "Landesführer" der Nationalen Front, die er 1936 auf die nationalsozialistische Ideologie verpflichtete. 1937 Besuch des Reichsparteitags der NSDAP in Nürnberg. 1938 Demission als Landesführer wegen innerparteilicher Opposition. 1939 bis zu deren Verbot Redaktor der Neuen Basler Zeitung. 1940 Mitbegründer der Nationalen Bewegung Schweiz (NBS); 1940-1943 Schriftleiter der Nationalen Hefte. 1944-1966 Geschäftsleitung des Presseausschnittdienstes Zeitungslupe in Zürich, den er 1947 mit dem Internationalen Argus der Presse fusionierte und die Firma künftig unter der Marke Argus führte. -

Like Museums, Videogames Aren't Neutral

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons Institute for the Humanities Theses Institute for the Humanities Summer 2019 Harbored: Like Museums, Videogames Aren't Neutral Stephanie Hawthorne Old Dominion University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/humanities_etds Part of the European History Commons, Mass Communication Commons, Museum Studies Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hawthorne, Stephanie. "Harbored: Like Museums, Videogames Aren't Neutral" (2019). Master of Arts (MA), thesis, Humanities, Old Dominion University, DOI: 10.25777/176r-k992 https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/humanities_etds/21 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Institute for the Humanities at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Institute for the Humanities Theses by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HARBORED: LIKE MUSEUMS, VIDEOGAMES AREN’T NEUTRAL by Stephanie Hawthorne B.A. May 2013, Old Dominion University A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Old Dominion University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS HUMANITIES OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY August 2019 Approved by: Kevin Moberly (Chair) Annette Finley-Croswhite (Member) Amy K. Milligan (Member) ABSTRACT HARBORED: LIKE MUSEUMS, VIDEOGAMES AREN’T NEUTRAL Stephanie Hawthorne Old Dominion University, 2019 Director: Dr. Kevin Moberly There are three primary components to be reviewed: (1) an essay (2) a videogame design document and (3) a prototype. The following essay is comprised of: (1) an analysis of scholarship and contemporary works regarding videogames and museums that demonstrate the theory and method behind this project, (2) research regarding an historic maritime event that will serve as the subject matter for the proposed videogame, and (3) a conclusion that summarizes the game design. -

O Yishuv E O Holocausto: a Relação Entre O Proto-Estado Judeu E O Extermínio Dos Judeus Na Diáspora

Revista Vértices No. 19 (2015) Departamento de Letras Orientais da Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo O YISHUV E O HOLOCAUSTO: A RELAÇÃO ENTRE O PROTO-ESTADO JUDEU E O EXTERMÍNIO DOS JUDEUS NA DIÁSPORA THE YISHUV AND THE HOLOCAUST: THE RELATION BETWEEN THE PRE- STATE AND THE EXTERMINATION OF THE JEWS IN DIASPORA Thaily Viviane André1 Resumo Um dos temas mais polêmicos da história do Estado de Israel, até hoje, é o grau de ciência dos líderes do Yishuv, proto-Estado judeu na Palestina sob mandato britânico, a respeito da magnitude da destruição da comunidade judaica na Europa pela Alemanha nazista, e o quanto fizeram para salvar esses judeus. Este artigo tem por objetivo tentar responder a essas complexas questões, além de apresentar o debate historiográfico dos principais autores que se aprofundaram na temática. Palavras-chave: Yishuv; Holocausto; resgate; debate historiográfico. Abstract Until today, one of the most controversial themes of the State of Israel history is about how much the leaders of the Yishuv, the Jewish pre-State in Palestine under British mandate, really knew about the magnitude of the destruction of the Jewish community in Europe by the Nazi Germany, and how much effort they put in saving these Jews. This article tries to answer such complex questions and to present the historiographic debate of the main authors who deepened on the subject. Keywords: Yishuv; Holocaust; rescue; historiographic debate. 1 Mestranda em Estudos Judaicos pelo Programa de Pós-Graduação em Estudos Judaicos e Árabes da Universidade de São Paulo. E-mail: [email protected] 26 Revista Vértices No. -

Reports of the Jewish Agency Executives Submitted to the Twenty-Second Zionist Congress at Basle, Excerpts Jewish Agency 1946

REPORTS OF THE JEWISH AGENCY EXECUTIVES SUBMITTED TO THE TWENTY-SECOND ZIONIST CONGRESS AT BASLE, EXCERPTS JEWISH AGENCY 1946 POLITICAL DEPARTMENT INTRODUCTION The period which has elapsed since the last Zionist Congress has been the most tragic in Jewish history. It has also been the most disastrous in the annals of modern Zionism. The last Congress met under the shadow of the Palestine White Paper of May, 1939. It broke up on the eve of the Second World War. Ominous anticipations filled the hearts of the delegates as they sped home, yet none could have foreseen the ghastly catastrophe that was to follow. In the course of a few years the bulk of European Jewry which, for fifteen centuries had been the principal center of Jewish life, was wiped out of existence. Entire communities with their ancient traditions, their synagogues, schools, colleges, libraries and communal institutions were destroyed overnight as by a tornado. A Satanic design to eradicate Jewish life for ever from the face of Europe led to the wholesale extermination of Jewish children. Of an estimated total of several million Jewish children on the continent of Europe before the War, only some tens of thousands are alive today. In this colossal tragedy, the Palestine white Paper played a significant part. It is not suggested that all the 6,000,000 Jews who were killed in Europe during the war could have been saved if there had been no White Paper, but there can be no doubt that many thousands of those who perished in the gas chambers of Poland would be alive today if immigration to Palestine had been regulated, as formerly, by the principle of the country’s absorptive capacity and had not been subjected to the arbitrary numerical restrictions imposed under the White Paper.