The Lairds of Glenlyon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Safap October2016 Minutes Final

Minutes of the meeting of THE SCOTTISH ARCHAEOLOGICAL FINDS ALLOCATION PANEL 10:45am, Thursday 27th October 2016 Present: Dr Evelyn Silber (Chair), Neil Curtis, Dr Murray Cook (via Skype), Jilly Burns (NMS), Paul MacDonald, Richard Welander (HES), Mary McLeod Rivett In attendance: Stuart Campbell (TTU), Dr Natasha Ferguson (TTU), Andrew Brown (QLTR Solicitor). Dr Natasha Ferguson took the minutes 1. Apologies Apologies from Jacob O’Sullivan (MGS). 2. Chair Remarks The Chair informed the panel that the QLTR had received a response from SG to a letter highlighting issues relating to increasing numbers of disclaimed cases. It was agreed the points would be discussed further at the Annual Review Meeting on 14th November. The panel agreed to form a sub-committee (of NC, JB, RW & AB) to deal with revisions of the Code of Practice in relation to multiple applications. The next date of the panel meeting confirmed as Thursday 23rd March 2017. Further dates in 2017 to be proposed. It is proposed that the number of meetings is reduced to three by combining the Annual Review meeting with a panel meeting. This will be discussed at the next Annual Review meeting on 14th November 2016. 3. Discussion of Galloway Hoard, valuations and timescales JB (NMS) was absent from this discussion. The panel were updated on the current status of the Galloway Hoard, including projected timescales for allocation. The panel also discussed the criteria for assessing the valuations. The 31st January 2017 was agreed as a proposed date to hold an extraordinary SAFAP meeting in relation to allocating the Galloway Hoard. -

The Post Office Perth Directory

i y^ ^'^•\Hl,(a m \Wi\ GOLD AND SILVER SMITH, 31 SIIG-S: STI^EET. PERTH. SILVER TEA AND COFFEE SERVICES, BEST SHEFFIELD AND BIRMINGHAM (!^lettro-P:a3tteto piateb Crutt mb spirit /tamtjs, ^EEAD BASKETS, WAITEKS, ^NS, FORKS, FISH CARVERS, ci &c. &c. &c. ^cotct) pearl, pebble, arib (STatntgorm leroeller^. HAIR BRACELETS, RINGS, BROOCHES, CHAINS, &c. PLAITED AND MOUNTED. OLD PLATED GOODS RE-FINISHED, EQUAL TO NEW. Silver Plate, Jewellery, and Watches Repaired. (Late A. Cheistie & Son), 23 ia:zc3-i3: sti^eet^ PERTH, MANUFACTURER OF HOSIERY Of all descriptions, in Cotton, Worsted, Lambs' Wool, Merino, and Silk, or made to Order. LADIES' AND GENTLEMEN'S ^ilk, Cotton, anb SEoollen ^\}xxi^ attb ^Mktt^, LADIES' AND GENTLEMEN'S DRAWERS, In Silk, Cotton, Worsted, Merino, and Lambs' Wool, either Kibbed or Plain. Of either Silk, Cotton, or Woollen, with Plain or Ribbed Bodies] ALSO, BELTS AND KNEE-CAPS. TARTAN HOSE OF EVERY VARIETY, Or made to Order. GLOVES AND MITTS, In Silk, Cotton, or Thread, in great Variety and Colour. FLANNEL SHOOTING JACKETS. ® €^9 CONFECTIONER AND e « 41, GEORGE STREET, COOKS FOR ALL KINDS OP ALSO ON HAND, ALL KINDS OF CAKES AND FANCY BISCUIT, j^jsru ICES PTO*a0^ ^^te mmU to ©vto- GINGER BEER, LEMONADE, AND SODA WATER. '*»- : THE POST-OFFICE PERTH DIRECTOEI FOR WITH A COPIOUS APPENDIX, CONTAINING A COMPLETE POST-OFFICE DIRECTORY, AND OTHER USEFUL INFORMATION. COMPILED AND ARRANGED BY JAMES MAESHALL, POST-OFFICE. WITH ^ pUtt of tl)e OTtts atiti d^nmxonn, ENGEAVED EXPRESSLY FOB THE WORK. PEETH PRINTED FOR THE PUBLISHER BY C. G. SIDEY, POST-OFFICE. -

Highland Perthshire Trail

HIGHLAND PERTHSHIRE TRAIL HISTORY, CULTURE AND LANDSCAPES OF HIGHLAND PERTHSHIRE THE HIGHLAND PERTHSHIRE TRAIL - SELF GUIDED WALKING SUMMARY Discover Scotland’s vibrant culture and explore the beautiful landscapes of Highland Perthshire on this gentle walking holiday through the heart of Scotland. The Perthshire Trail is a relaxed inn to inn walking holiday that takes in the very best that this wonderful area of the highlands has to offer. Over 5 walking days you will cover a total of 55 miles through some of Scotland’s finest walking country. Your journey through Highland Perthshire begins at Blair Atholl, a small highland village nestled on the banks of the River Garry. From Blair Atholl you will walk to Pitlochry, Aberfeldy, Kenmore, Fortingall and then to Kinloch Rannoch. Several rest days are included along the way so that you have time to explore the many visitor attractions that Perthshire has to offer the independent walker. Every holiday we offer features hand-picked overnight accommodation in high quality B&B’s, country inns, and guesthouses. Each is unique and offers the highest levels of welcome, atmosphere and outstanding local cuisine. We also include daily door to door baggage transfers, route notes and detailed maps and Tour: Highland Perthshire Trail pre-departure information pack as well as emergency support, should you need it. Code: WSSHPT1—WSSHPT2 Type: Self-Guided Walking Holiday Price: See Website HIGHLIGHTS Single Supplement: See Website Dates: April to October Walking Days: 5—7 Exploring Blair Castle, one of Scotland’s finest, and the beautiful Atholl Estate. Nights: 6—8 Start: Blair Atholl Visiting the fascinating historic sites at the Pass of Killiecrankie and Loch Tay. -

Line of March

NYC TARTAN DAY PARADE - April 9, 2016 LINE OF MARCH FIRST DIVISION: West 44th Street from 6th Avenue to 5th Avenue Section 1: Forms from corner of 6th Avenue East to 59 West 44th Street 1. NYC Police Department Mounted Unit (forms on 6th Avenue above W. 45th Street) 2. U.S. Military Academy (West Point) Pipes and Drums 3. Grand Marshal Banner 4. Grand Marshal Sam Heughan (with family/friends ) 5. St. Andrew’s Color Guard 6. NTDNYC Banner 7. Edinburgh Academy Pipe and Drum Band 8. National Tartan Day New York Parade Committee 9. BARBOUR 10. U.S. Naval Academy (Annapolis) Pipes and Drums 11. Scottish American Military Society Color Guard 12. VIPs: Hon. Tricia Marwick, MSP; Fergus Cochrane 13. Scottish Parliament/Politicians/U.S. Politicians 14. Visit Scotland Section 2: Forms from 59 West 44th Street to 37 West 44th Street 1. Mt. Kisco Scottish Pipes and Drums 2. St. Andrew’s Society of New York 3. New York Caledonian Club Pipe Band 4. New York Caledonian Club 5. New York Metro Pipe Band 6. American Scottish Foundation 7. Tri-County Pipes and Drums 8. Clan Fraser 9. Clan Ross 10. St. Andrew’s Society; City of Albany 11. Pipes and Drums of the Atlantic Watch 12. Daughters of Scotia - 1 - Section 2: Continued 13. Daughters of the British Empire 14. Clan Abernathy of Richmond 15. CARNEGIE HALL Section 3: Forms from 37 West 44th Street to 27 West 44th Street 1. NYC Police Department Marching Band 2. Clan Malcolm/Macallum 3. Clan MacIneirghe 4. Long Island Curling Club 5. -

Anne R Johnston Phd Thesis

;<>?3 ?3@@8393;@ 6; @53 6;;3> 530>623? 1/# *%%"&(%%- B6@5 ?=316/8 >343>3;13 @< @53 6?8/;2? <4 9A88! 1<88 /;2 @6>33 /OOG ># 7PJOSTPO / @JGSKS ?UDNKTTGF HPR TJG 2GIRGG PH =J2 CT TJG AOKVGRSKTY PH ?T# /OFRGWS &++& 4UMM NGTCFCTC HPR TJKS KTGN KS CVCKMCDMG KO >GSGCREJ.?T/OFRGWS,4UMM@GXT CT, JTTQ,$$RGSGCREJ"RGQPSKTPRY#ST"COFRGWS#CE#UL$ =MGCSG USG TJKS KFGOTKHKGR TP EKTG PR MKOL TP TJKS KTGN, JTTQ,$$JFM#JCOFMG#OGT$&%%'($'+)% @JKS KTGN KS QRPTGETGF DY PRKIKOCM EPQYRKIJT Norse settlement in the Inner Hebrides ca 800-1300 with special reference to the islands of Mull, Coll and Tiree A thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Anne R Johnston Department of Mediaeval History University of St Andrews November 1990 IVDR E A" ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS None of this work would have been possible without the award of a studentship from the University of &Andrews. I am also grateful to the British Council for granting me a scholarship which enabled me to study at the Institute of History, University of Oslo and to the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs for financing an additional 3 months fieldwork in the Sunnmore Islands. My sincere thanks also go to Prof Ragni Piene who employed me on a part time basis thereby allowing me to spend an additional year in Oslo when I was without funding. In Norway I would like to thank Dr P S Anderson who acted as my supervisor. Thanks are likewise due to Dr H Kongsrud of the Norwegian State Archives and to Dr T Scmidt of the Place Name Institute, both of whom were generous with their time. -

2020 Cruise Directory Directory 2020 Cruise 2020 Cruise Directory M 18 C B Y 80 −−−−−−−−−−−−−−− 17 −−−−−−−−−−−−−−−

2020 MAIN Cover Artwork.qxp_Layout 1 07/03/2019 16:16 Page 1 2020 Hebridean Princess Cruise Calendar SPRING page CONTENTS March 2nd A Taste of the Lower Clyde 4 nights 22 European River Cruises on board MS Royal Crown 6th Firth of Clyde Explorer 4 nights 24 10th Historic Houses and Castles of the Clyde 7 nights 26 The Hebridean difference 3 Private charters 17 17th Inlets and Islands of Argyll 7 nights 28 24th Highland and Island Discovery 7 nights 30 Genuinely fully-inclusive cruising 4-5 Belmond Royal Scotsman 17 31st Flavours of the Hebrides 7 nights 32 Discovering more with Scottish islands A-Z 18-21 Hebridean’s exceptional crew 6-7 April 7th Easter Explorer 7 nights 34 Cruise itineraries 22-97 Life on board 8-9 14th Springtime Surprise 7 nights 36 Cabins 98-107 21st Idyllic Outer Isles 7 nights 38 Dining and cuisine 10-11 28th Footloose through the Inner Sound 7 nights 40 Smooth start to your cruise 108-109 2020 Cruise DireCTOrY Going ashore 12-13 On board A-Z 111 May 5th Glorious Gardens of the West Coast 7 nights 42 Themed cruises 14 12th Western Isles Panorama 7 nights 44 Highlands and islands of scotland What you need to know 112 Enriching guest speakers 15 19th St Kilda and the Outer Isles 7 nights 46 Orkney, Northern ireland, isle of Man and Norway Cabin facilities 113 26th Western Isles Wildlife 7 nights 48 Knowledgeable guides 15 Deck plans 114 SuMMER Partnerships 16 June 2nd St Kilda & Scotland’s Remote Archipelagos 7 nights 50 9th Heart of the Hebrides 7 nights 52 16th Footloose to the Outer Isles 7 nights 54 HEBRIDEAN -

A Guide to Perth and Kinross Councillors

A Guide to Perth and Kinross Councillors Who’s Who Guide 2017-2022 Key to Phone Numbers: (C) - Council • (M) - Mobile Alasdair Bailey Lewis Simpson Labour Liberal Democrat Provost Ward 1 Ward 2 Carse of Gowrie Strathmore Dennis Melloy Conservative Tel 01738 475013 (C) • 07557 813291 (M) Tel 01738 475093 (C) • 07909 884516 (M) Email [email protected] Email [email protected] Ward 2 Strathmore Angus Forbes Colin Stewart Conservative Conservative Ward 1 Ward 2 Carse of Gowrie Strathmore Tel 01738 475034 (C) • 07786 674776 (M) Email [email protected] Tel 01738 475087 (C) • 07557 811341 (M) Tel 01738 475064 (C) • 07557 811337 (M) Email [email protected] Email [email protected] Provost Depute Beth Pover Bob Brawn Kathleen Baird SNP Conservative Conservative Ward 1 Ward 3 Carse of Gowrie Blairgowrie & Ward 9 Glens Almond & Earn Tel 01738 475036 (C) • 07557 813405 (M) Tel 01738 475088 (C) • 07557 815541 (M) Email [email protected] Email [email protected] Fiona Sarwar Tom McEwan Tel 01738 475086 (C) • 07584 206839 (M) SNP SNP Email [email protected] Ward 2 Ward 3 Strathmore Blairgowrie & Leader of the Council Glens Tel 01738 475020 (C) • 07557 815543 (M) Tel 01738 475041 (C) • 07984 620264 (M) Murray Lyle Email [email protected] Email [email protected] Conservative Caroline Shiers Ward 7 Conservative Strathallan Ward 3 Ward Map Blairgowrie & Glens Tel 01738 475037 (C) • 07557 814916 (M) Tel 01738 475094 (C) • 01738 553990 (W) Email [email protected] Email [email protected] Ward 11 Perth City North Ward 12 Ward 4 Perth City Highland -

Camping Pocket Guide

CONTENTS Get Ready for Camping 04 Add To Your Experience 07 Enjoy Family Picnics 08 Scenic Scotland 10 Visit National Parks 14 Amazing Wildlife 16 GET READY FOR CAMPING - Stargazing - Experience the freedom of a touring trip, where you can Sleeping under the stars is the perfect opportunity to wake up in a different part of the country every day. Or get familiar with the wonders of the sky at night. Plan enjoy a bit of luxury at a holiday park and spend a restful a camping trip to the Glentrool Camping and Caravan week in the comfy surrounds of a state-of-the-art static Site in the Galloway Forest Park, the UK’s first Dark Sky caravan, or pack in some fun activities with the kids. Park, or sail to Scotland’s first Dark Sky island. There’s There’s a camping and caravanning holiday in Scotland minimum light pollution on the Isle of Coll, where the to suit every preference and budget. nearest lamppost is 20 miles away! Start planning a break today and find your perfect Experience more stargazing opportunities and discover camping or caravanning destination. Scotland’s inky black skies on our website. - Stunning views - - Campsites near castles - Summer is the time to be spontaneous – pack the tent Why not combine your camping or caravanning trip into the car, head out onto the open road, and pitch up in with a bit of history and book a pitch in the grounds of a some beautiful locations. You’ll find campsites set below castle? You’ll find such camping grounds in many parts breathtaking mountain ranges, overlooking pristine of the country, from the impressive 18th century Culzean beaches, or in the middle of lush, open countryside. -

Ideas to Inspire

2016 - Year of Innovation, Architecture and Design Speyside Whisky Festival Dunrobin Castle Dunvegan Castle interior Harris Tweed Bag Ideas to inspire Aberdeenshire, Moray, Speyside, the Highlands and the Outer Hebrides In 2016 Scotland will celebrate and showcase its historic and contemporary contributions to Innovation, Architecture and Events: Design. We’ll be celebrating the beauty and importance of our Spirit of Speyside Whisky Festival - Early May – Speyside whiskies are built heritage, modern landmarks and innovative design, as well famous throughout the world. Historic malt whisky distilleries are found all as the people behind some of Scotland’s greatest creations. along the length of the River Spey using the clear water to produce some of our best loved malts. Uncover the development of whisky making over the Aberdeenshire is a place on contrasts. In the city of Aberdeen, years in this stunning setting. www.spiritofspeyside.com ancient fishing traditions and more recent links with the North Festival of Architecture - throughout the year – Since 2016 is our Year of Sea oil and gas industries means that it has always been at the Innovation, Architecture and Design, we’ll celebrate our rich architectural past and present with a Festival of Architecture taking place across the vanguard of developments in both industries. Aberdeenshire, nation. Morayshire and Strathspey and where you can also find the Doors Open Days - September – Every weekend throughout September, greatest density of castles in Scotland. buildings not normally open to the public throw open their doors to allow visitors and exclusive peak behind the scenes at museums, offices, factories, The rugged and unspoiled landscapes of the Highlands of and many more surprising places, all free of charge. -

Committee Minutes 12Th March 2020

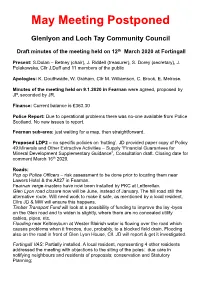

May Meeting Postponed Glenlyon and Loch Tay Community Council Draft minutes of the meeting held on 12th March 2020 at Fortingall Present: S.Dolan – Betney (chair), J. Riddell (treasurer), S. Dorey (secretary), J. Polakowska, Cllr J.Duff and 11 members of the public Apologies: K. Douthwaite, W. Graham, Cllr M. Williamson, C. Brook, E. Melrose. Minutes of the meeting held on 9.1.2020 in Fearnan were agreed, proposed by JP, seconded by JR. Finance: Current balance is £363.30 Police Report: Due to operational problems there was no-one available from Police Scotland. No new issues to report. Fearnan sub-area: just waiting for a map, then straightforward. Proposed LDP2 – no specific policies on ‘hutting’. JD provided paper copy of Policy 49:Minerals and Other Extractive Activities – Supply “Financial Guarantees for Mineral Development Supplementary Guidance”, Consultation draft. Closing date for comment March 16th 2020. Roads: Pop up Police Officers – risk assessment to be done prior to locating them near Lawers Hotel & the A827 in Fearnan. Fearnan verge-masters have now been installed by PKC at Letterellan. Glen Lyon road closure now will be June, instead of January. The hill road still the alternative route. Will need work to make it safe, as mentioned by a local resident. Cllrs JD & MW will ensure this happens. Timber Transport Fund will look at a possibility of funding to improve the lay -byes on the Glen road and to widen is slightly, where there are no concealed utility cables, pipes, etc. Flooding near Keltneyburn at Wester Blairish water is flowing over the road which causes problems when it freezes, due, probably, to a blocked field drain. -

Chapter 27 Our Lyon Family Ancestry

Chapter 27 Our Lyon Family Ancestry Introduction Just when I think I have run out of ancestors to write about, I find another really interesting one, and that leads to another few weeks of research. My last narrative was about our Beers family ancestors, going back to Elizabeth Beers (1663-1719), who married John Darling Sr. (1657-1719). Their 2nd-great granddaughter, Lucy Ann Eunice Darling (1804-1884), married Amzi Oakley (1799-1853). Lucy Ann Eunice Darling’s parents were Samuel Darling (1754- 1807) and Lucy Lyon (1760-1836). All of these relationships are detailed in the section of the “Quincy Oakley” family tree that is shown below: In looking at this part of the family tree, I realized that I knew absolutely nothing about Lucy Lyon [shown in the red rectangle in the lower-right of the family tree on the previous page] other than the year she was born (1760) and the year she died (1836). I didn’t even know where she lived (although Fairfield County, Connecticut, would have been a good guess). What was her ancestry? When did her ancestors come to America? Where did they live before that? To whom are we related via the Lyon family connection? So after another few weeks of work, I now can tell her story. And it is a pretty good one! The Lyon Family in Fairfield, Connecticut Lucy Lyon was descended from Richard Lyon Jr. (1624-1678), who was one of three Lyon brothers who emigrated from Scotland in the late 1640’s. In 1907, a book was published about this family, entitled Lyon Memorial, and of course, it has been digitized and is available online:1 1 https://archive.org/details/lyonmemorial00lyon The story of the three Lyon brothers (Henry, Thomas, and Richard Jr.) in the New World begins with the execution (via beheading) of King Charles I in London, England, on 30 January 1649 (although the Lyon Memorial book has it as 1648). -

The Norse Influence on Celtic Scotland Published by James Maclehose and Sons, Glasgow

i^ttiin •••7 * tuwn 1 1 ,1 vir tiiTiv^Vv5*^M òlo^l^!^^ '^- - /f^K$ , yt A"-^^^^- /^AO. "-'no.-' iiuUcotettt>tnc -DOcholiiunc THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND PUBLISHED BY JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS, GLASGOW, inblishcre to the anibersitg. MACMILLAN AND CO., LTD., LONDON. New York, • • The Macmillan Co. Toronto, • - • The Mactnillan Co. of Canada. London, • . - Simpkin, Hamilton and Co. Cambridse, • Bowes and Bowes. Edinburgh, • • Douglas and Foults. Sydney, • • Angus and Robertson. THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND BY GEORGE HENDERSON M.A. (Edin.), B.Litt. (Jesus Coll., Oxon.), Ph.D. (Vienna) KELLY-MACCALLUM LECTURER IN CELTIC, UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW EXAMINER IN SCOTTISH GADHELIC, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON GLASGOW JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS PUBLISHERS TO THE UNIVERSITY I9IO Is buaine focal no toic an t-saoghail. A word is 7nore lasting than the world's wealth. ' ' Gadhelic Proverb. Lochlannaich is ànnuinn iad. Norsemen and heroes they. ' Book of the Dean of Lismore. Lochlannaich thi'eun Toiseach bhiir sgéil Sliochd solta ofrettmh Mhamiis. Of Norsemen bold Of doughty mould Your line of oldfrom Magnus. '' AIairi inghean Alasdair Ruaidh. PREFACE Since ever dwellers on the Continent were first able to navigate the ocean, the isles of Great Britain and Ireland must have been objects which excited their supreme interest. To this we owe in part the com- ing of our own early ancestors to these isles. But while we have histories which inform us of the several historic invasions, they all seem to me to belittle far too much the influence of the Norse Invasions in particular. This error I would fain correct, so far as regards Celtic Scotland.