From Isolation to Collaboration: an Autoethnographic Account

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

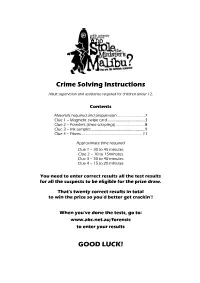

Crime Solving Instructions GOOD LUCK!

Crime Solving Instructions Adult supervision and assistance required for children under 12. Contents Materials required and preparation...............................2 Clue 1 – Magnetic swipe card .........................................3 Clue 2 – Powders (shoe scrapings)................................8 Clue 3 – Ink samples ...........................................................9 Clue 4 – Fibres ................................................................... 11 Approximate time required Clue 1 – 30 to 45 minutes Clue 2 – 10 to 15minutes Clue 3 – 30 to 40 minutes Clue 4 – 15 to 20 minutes You need to enter correct results all the test results for all the suspects to be eligible for the prize draw. That’s twenty correct results in total to win the prize so you’d better get crackin’! When you’ve done the tests, go to: www.abc.net.au/forensic to enter your results GOOD LUCK! MATERIALS REQUIRED AND PREPARATION No special science equipment is required to solve the case. All you’ll need is your forensic evidence kit and the following materials. You should read all the instructions carefully before you begin. Remember, you only have a small amount of evidence. Making a mistake could be costly! Clue Equipment Required Preparation / Notes . 1. Swipe y Evidence: the swipe card This is the most labour intensive clue. Card y Black magnetic powder You’ll be amazed at the result from the (provided in kit in plastic vial with swipe card … then you have to do some clear lid) maths (that’s right, maths!) y Scale map of Gold Coast City (provided in kit) You should work over a sheet of white A3 y Clear sticky tape or A4 paper when using the magnetic y White paper (A4 + A3 if available) powder! Excess powder should be y Scissors returned to the container - not discarded! y Dividers or compass (if available) The small amount provided should be y Rulers sufficient to repeat the test at least five y Calculator . -

PLAYLIST 900 Songs, 2.3 Days, 7.90 GB

Page 1 of 17 MAIN PLAYLIST 900 songs, 2.3 days, 7.90 GB Name Time Album Artist 1 Waterloo 2:43 101 Hits - Are We There Yet?! - CD4 Abba 2 Hello 3:57 ADELE 3 They Should Be Ringing (Single Edit) 3:28 Adore 4 The Memory Reel 3:24 LEAVES Advrb 5 You Look Good In Blue 2:18 triple j Unearthed Al Parkinson 6 Closer 3:55 Alana Wilkinson Alana Wilkinson 7 Good For You 3:37 Good For You Alana Wilkinson 8 fixture picture 4:07 Designer Aldous Harding 9 Good Conversation 3:16 The Turning Wheel Alex Hallahan 10 Don't Be So Hard On Yourself 4:18 Alex Lahey 11 Everybody's Laughing 3:50 Watching Angels Mend Alex Lloyd 12 Easy Exit Station 3:01 Watching Angels Mend Alex Lloyd 13 January 3:03 Ali Barter 14 I Feel Better But I Don't Feel Good 3:32 Alice Skye 15 Push 3:14 Alta 16 Remember That Sunday 2:37 Alton Ellis 17 Keep My Cool (with intro) 3:01 Aluka 18 Moana Lisa 3:44 I Woke Up This Morning After a Dream Amaringo 19 Sacred 4:44 Amaringo 20 I Got You 2:58 Love Monster Amy Shark 21 All Loved Up 3:30 Love Monster Amy Shark 22 Sisyphus 4:07 Andrew Bird 23 The Beloved - with intro 5:57 Carved Upon the Air Anecdote 24 The Sea - with intro 4:25 Carved Upon the Air Anecdote 25 No Secrets 4:18 101 Aussie Hits [CD2] The Angels 26 Pasta 4:38 Salt Angie McMahon 27 Missing Me 3:17 Salt Angie McMahon 28 Ring My Bell 3:17 Gold_Sensational 70's_ [Disc 1] Anita Ward 29 Nobody Knows Us - with intro 4:44 Nobody Knows Us Anna Cordell 30 You - with intro 5:41 Nobody Knows Us Anna Cordell 31 Train In Vain 4:44 Medusa Annie Lennox 32 Pale Bue Dot 3:04 Stay Fresh Annual -

THEATRES University of W.A Ephemera PR8065/THE

THEATRES University of W.A Ephemera PR8065/THE To view items in the Ephemera collection, contact the State Library of Western Australia CALL NO. DESCRIPTION PR8065/THE/1 A review of the inaugural production at the New Fortune. Nation an Independent Journal of Opinion. Issue No 137. 8 February 1964 PR8065/THE/2 Telegrams received for the New Fortune to 28 January 1964. PR8065/THE/3 The deliciously irreverent Nola Rae. Octagon Theatre. 1-4 September 1979 PR8065/THE/4 Visiting English Clairvoyants/Mediums. Leaflet. The Octagon Theatre. May 1982 D PR8065/THE/5 Women beware women. Thomas Middleton's Great Jacobean Tragedy. Octagon Theatre. April 1982 PR8065/THE/6 Grand Variety Concert arranged by Toc-H. Octagon Theatre. August 1982 D PR8065/THE/7 The Kodaly Hungarian Folkloric Ensemble. Octagon Theatre. January 1983 PR8065/THE/8 John and Bernadette Taylor Ballet School presents 'The Magic of Alice in Wonderland'. Octagon Theatre. June 1983 PR8065/THE/9 The San Quentin Drama Workshop. Octagon Theatre. July c1986 PR8065/THE/10 'Armide', an opera by Jean Baptiste Lully. Octagon Theatre. September c1986 PR8065/THE/11 'The Taming of the Shrew' by Will Shakespeare. Octagon Theatre. June c1986 PR8065/THE/12 Especially for Mother's Day. Singers of note. Octagon Theatre. June c1986 PR8065/THE/13 'The measures taken'. Brecht. Octagon Theatre. September c1986 PR8065/THE/14 A Noel Coward Gala. Octagon Theatre. October c1987 PR8065/THE/15 The 1980 Dolly Awards. Dolphin Theatre. June c1987 PR8065/THE/16 Auditions for 'A Midsummer Night's Dream'. Dolphin Theatre. June c1987 PR8065/THE/17 'Let's talk backwards'. -

VASE in Social Media Ask and You Will Receive...* * Make Sure You

NEWS July 2013 It’s a story heard all too often: another friend who is faced with having to deal with the diagnosis of a life threatening illness. Ron Delbridge, long time friend and VASE supporter is currently going through this battle. As helpless as we all feel to deal with this relentless disease, we gain some strength in being able to do whatever we can to support and encourage the person affected. A group of generous and talented folks have planned an event to show their affection, concern and support for Ronnie. The flyer below has the details. VASE will be there. Hope you will be too! Vic Kena, pictured left is helping organize the event. PA is being provided courtesy of Tonepacer Live Production (http://www. tonepacer.com) with backline from The GBH Rock Shop (http:// www.westendmusic.com.au). Vase will supply guitar amps. Vic Kena and Ron Delbridge on the VASE stand at the 2010 Guitar Show in Brisbane Ask and You Will Receive...* Received a note recently from Paul Smith: “ I see that Epicure (a Ballarat band, if I’m not mistaken) have some history with Vase. I will have to check out your Facebook page for the videos. Epicure has been one of my favourite bands for some years, especially for their sublime blues guitar and bass tones on the “Goodbye Girl” album. I was very disappointed when they broke up a few years ago, as I never got to see them live. I would love to know more about their use of Vase gear in their studio and live career. -

Post- Convention Update

OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF AADA | SEPTEMBER 2017 | ISSUE 20.5 SPECIAL POST CONVENTION UPDATE EDITION POST- CONVENTION UPDATE AADA ANNOUNCES POWERFUL DATA MAPPING TOOL A NEW ERA IN ADVOCACY AUSTRALIA'S DEALERS COME TOGETHER FOR AADA 2017 ASIC ON THE SALE OF ADD-ON INSURANCE AND WARRANTIES MASSIVE RISE IN AUTOMOTIVE ADVERTISING THE CHANGING LANDSCAPE OF PROFITABILITY www.automotivedealer.com.au PRINT POST 100019106 Craig Lowndes, TeamVor tex The # 1 choice of TeamVortex and 40,000 other businesses Make it Yours 1300 362 415 mtaasuper.com.au 06/17 2017 Conexus Financial Superannuation Awards Medium Fund of the year The Conexus Financial Superannuation Awards are determined using proprietary methodologies. Awards were issued March 9, 2017 and are solely statements of opinion and do not represent recommendations to purchase, hold, or sell any securities or make any other investment decisions. Ratings are subject to change. This document is issued by Motor Trades Association of Australia Superannuation Fund Pty. Limited (ABN 14 008 650 628, AFSL 238 718) of Level 3, 39 Brisbane Avenue Barton ACT 2600, Trustee of the MTAA Superannuation Fund (ABN 74 559 365 913). Motor Trades Association of Australia Superannuation Fund Pty. Limited has ownership interests in Industry Super Holdings Pty Ltd and Members Equity Bank Limited. The information provided is of a general nature and does not take into account your specifi c needs or personal situation. You should assess your fi nancial position and personal objectives before making any decision based on this information. We also recommend that you seek advice from a licensed fi nancial adviser. -

WEEK 17: Sunday, 21 April

WEEK 17: Sunday, 21 April - Saturday, 27 April 2019 EASTERN STATES (NSW, QLD, ACT, TAS, VIC) Start Consumer Closed Date Genre Title Episode Title Series Episode TV Guide Text Country of Origin Language Year Repeat Classification Subtitles Time Advice Captions 2019-04-21 0500 News - Overseas Korean News Korean News 0 News via satellite from YTN Korea, in Korean, no subtitles. SOUTH KOREA Korean-100 2013 NC 2019-04-21 0530 News - Overseas Indonesian News Indonesian News 0 News via satellite from TVRI Jakarta, in Indonesian, no subtitles. INDONESIA Indonesian-100 2013 NC 2019-04-21 0610 News - Overseas Hong Kong News Hong Kong News 0 News via satellite from TVB Hong Kong, in Cantonese, no subtitles. HONG KONG Cantonese-100 2013 NC 2019-04-21 0630 News - Overseas Chinese News Chinese News 0 News via satellite from CCTV Beijing, in Mandarin, no subtitles. CHINA Mandarin-100 2013 NC 2019-04-21 0700 News - Overseas Russian News Russian News 0 News via satellite from NTV Moscow, in Russian, no subtitles. RUSSIA Russian-100 2013 NC 2019-04-21 0730 News - Overseas Polish News Polish News 0 Wydarzenia from Polsat in Warsaw via satellite, in Polish, no subtitles. POLAND Polish-100 2013 NC 2019-04-21 0800 News - Overseas Maltese News Maltese News 0 News from Public Broadcasting Services Limited, Malta, in Maltese, no subtitles. MALTA Maltese-100 2013 NC News via satellite from public broadcaster MRT in Skopje, in Macedonian, no 2019-04-21 0830 News - Overseas Macedonian News Macedonian News 0 MACEDONIA Macedonian-100 2013 NC subtitles. 2019-04-21 0900 News - Overseas Croatian News Croatian News 0 News via satellite from HRT Croatia, in Croatian, no subtitles. -

Oz Acts Chart on Growing Pains 2 Labels' Distribution

T H E L A T E S T N E W S I E nternatìonaA N D V W S F R O M A R O U N D T H E W O R L D Oz Acts Chart On Growing Pains Spain's GVM Pìeks Up 3 Teen Groups Score Big For Indies; Majors To Enter The Fray BY CHRISTIE ELIEZER Amorosi was discovered by co- keting director of international at 2 labels' MELBOURNE, Australia -As the manager Jack Strom in 1997 as a 15- BMG Australia, "This market is Distribution latest graduates from the Australian year-old, singing in a Russian rest- incredibly receptive to teen acts. You BY HOWELL LLEWELLYN own acts there. annex of rock'n'roll high school make aurant in Melbourne. Strom and his need an AC radio format, and the MADRID -The new powerhouse on Until now, Fonovisa -the Mexican their mark on the music scene down business partner, Mark Holden, [national] Austereo network is perfect Spain's music scene, Gran Vía Musi- label that brought Enrique Iglesias under, the next class of contenders is signed her to their management com- for that. You need receptive TV video cal (GVM), has picked up local dis- to worldwide attention -has been already turning its attention from pany, MarJac Productions, in 1998. shows like [the Ten Network's] `Video tribution rights for two leading Lati- distributed worldwide through Uni- exam results to chart positions. Amorosi is a Transistor Music Hits' and glossy magazines like no labels, Fonovisa and Karen versal. Fonovisa's catalog includes Three of the major artist in Australia and Smash Hits and TV Hits. -

Meet Killing Heidi in Airlie Beach Win a Backstage Rendezvous with Australia’S Favourite Rock Siblings

For Immediate Release October 18, 2018 Meet Killing Heidi in Airlie Beach Win a backstage rendezvous with Australia’s favourite rock siblings If ‘Weir’ or ‘Mascara’ are the songs that take you back to 1999, don’t miss the chance to get up close and personal with the band behind them in Airlie Beach. Fans who buy a three-day pass to the Airlie Beach Festival of Music from now until October 31 will be entered into a draw for a meet and greet with Australia’s favourite rock siblings, Jesse and Ella Hooper. The lucky winner will be taken backstage an hour before the band’s main stage performance on Saturday, November 10, and will walk away with a photograph and signed merchandise. Frontwoman Ella Hooper said she and Jesse always loved meeting people who appreciated their songs. “Part of the reason for returning to the Killing Heidi material has been the positive response from our fans,” she said. “So definitely come and check out our set at the festival. “We play all our hits and songs that people know and love – from ‘Weir’, ‘Mascara’ and ‘I am’, (as well as) some old more eclectic favourites.” Jesse Hooper said Killing Heidi couldn’t wait to rock Airlie Beach. “We haven’t played up there for over a decade so we’re looking forward to some sun and great festival tunes,” he said. Festival founder Gavin Butlin said there were so many Killing Heidi fans it would mean the world to any one of them to meet their idols in the flesh. -

Made in Melbourne! Enjoyed Nationally & Internationally!

NOVEMBER 2013 Made in Melbourne! Enjoyed Nationally & Internationally! NOVEMBER 2013 Issue 107 q comment: q.magazine.australia Our Travel Editor, Barrie Mahoney has a new Publisher & Editor book out now called: Escape to the Sun so of Brett Hayhoe course I had to promote it for him. +61 (0) 422 632 690 [email protected] People will always have dreams and passions, for that is the true essence of the human condition. For some, Editorial / Sales & Marketing this may mean a larger home, a new car, or climbing [email protected] a mountain. For many others, like myself, it is the [email protected] dream of a new life, new experiences, new cultures, the opportunity to experience, taste and smell the Design excitement in a place that is of our own choosing and Uncle Brett Designs & Graphics not merely based upon an accident of birth. Contributing Writers Evan Davis, Alan Mayberry, Tasman Anderson, For many, the dreams will be of a less stressful life, an Barrie Mahoney, Brett Hayhoe, Matteo Snooks, opportunity to be challenged by new experiences, new Nathan Miller, David Luhrs and exciting work opportunities, a place where there is a high quality of life in which a young family may Cover picture grow. For others, it may be the dream of a carefree, Christine and Virginia long, happy and healthy retirement, but for all it is an ‘Escape to the Sun’. Photographic Contributions Alan Mayberry (gh, q comm, q drag), ISBN: 9780957544444 Mel Hill Photography (flamingos), Available as paperback, Kindle and iBook Daniel Martin Bailey (robarta, dnm, q drag), Dean Robertson (dts), Jeff Busby (q world premier) [email protected] Distribution [email protected] ISSN 1449-499X QMAGAZINE PO Box 7479, St. -

2018 Program

THE YEPPO ON • CAPRICORN COAST 10 - 12 AUGUST 2 018 thevillagefestival.org.au 2018 Program CQUNIVERSITY PROUD TO SUPPORT CQ’S PREMIER MUSIC, ARTS AND CULTURAL EVENT SEE YOU AT THE CQUNIVERSITY VILLAGE FESTIVAL 2018 CRICOS Code: 00219C | RTO Code: 40939 J_AD_180222 Welcome MESSAGE FROM THE MINISTER FOR WELCOME TO THE TOURISM INDUSTRY DEVELOPMENT 2018 FESTIVAL Welcome to the Capricorn This year is a momentous one organisations will be supplemented Coast for The CQUniversity for the Village Festival. We by sponsorship from a number of Village Festival. have signed a three-year well-known local businesses. Memorandum of Understanding Much loved venues such as the Now in its sixteenth year, this (MoU) with CQUniversity Queen Street Community Hall and event is central Queensland’s who will continue as naming The Strand will be joined by Keppel premier music, arts and cultural Bay Sailing Club to host a variety celebration. rights sponsor until 2021. The assurance of ongoing financial of entertainment throughout the Over the three festival days you backing from such a respected weekend, giving attendees more will experience a vibrant mix of regional organisation helps the choice. On behalf of the Board, music, performing arts, workshops Festival Board to plan better I am most grateful for this level of support as it demonstrates the and food, overlooking stunning for the future, and will facilitate Keppel Bay. recognition of the Festival in the life Congratulations to the event greater involvement of the of the Capricorn Coast. Events like The CQUniversity organisers and all involved in University and its students in Our aim, in concert with all who Village Festival are vital to the ensuring the delivery of this Festival activities. -

Celebrating the Songs of Joni Mitchell

BOTH SIDES NOW - Celebrating the Songs of Joni Mitchell KATE MILLER-HEIDKE is an award-winning singer-songwriter who traverses the worlds of contemporary pop, folk and opera. She has released 4 albums in Australia, achieving multi-platinum status and appearing in the top 10 album and singles charts numerous times. Her latest album O Vertigo! debuted at number 4 on the Australian album charts, broke Australian crowdfunding records and was nominated for an ARIA award. Her previous albums include Nightflight, which reached number 2 on the ARIA chart, and Curiouser, which reached double platinum sales in Australia and spawned the multi-platinum hits ‘Last Day On Earth’ and ‘Caught In The Crowd’. In 2009 she became the first Australian to win the grand prize in the International Songwriting Competition for ‘Caught in the Crowd’. Trained as a classical singer at the Queensland Conservatorium, Kate has appeared at the Metropolitan Opera in New York in John Adams' The Death of Klinghoffer, and has performed several roles for the English National Opera. Her debut opera as a composer, The Rabbits (based on the book by Shaun Tan and John Marsden), was commissioned by Opera Australia and premiered at the Perth Festival in February 2015, followed by sold out seasons in Melbourne, Sydney and Brisbane. It won 4 Helpmann Awards including Best Score and Best New Australian Work. In 2015 Kate broke into national television, starring in The Divorce, a four-part ABC mini- series. Both The Rabbits and The Divorce were nominated for Best Soundtrack/Cast Recording at the 2016 ARIA Awards. -

NEWMEDIA As Soon As I Saw My Mate Phil’S Print out from an Apple Mac Postal Address: Computer in 1989 a Light Bulb Went Off in My Head

Celebrating Volume 31. 1 & 2 Jocks’ Journal 30yrs January 1-31,2019 “Australia’s longest running radio industry publication” Jocks’ Journal Celebrates 30 Years NEWMEDIA As soon as I saw my mate Phil’s print out from an Apple Mac Postal Address: computer in 1989 a light bulb went off in my head. I then Brisbane realised it was now possible to 'have a go' at an idea I had for PO Box 2363 an ‘almanac’ trivia publication for radio presenters. For years Mansfield BC Qld 4122 I had collected ‘famous birthdays’ and ‘on this day’ trivia. I Web Address: suppose the seeds go back to the fact that I diligently kept a www.newmedia.com.au daily diary from all my high school years and beyond. Now as Email: we were entering a new age in computers and technology it [email protected] was possible to do ‘desk top publishing’. Phone Contacts: In January 1989 I borrowed my mate’s Apple computer, paid my friend Kerry to laser print a master Office: (07) 3422 1374 copy, then photocopied a sample edition for every commercial radio station and did a test run. Mobile: 0407 750 694 On January 25 we signed up our first subscriber. A fax came through confirming that a young4ZR announcer Clive Burnell (sadly passed on) had signed up. From then on the subscriptions kept rolling in and we never looked back. The first JJ only included an almanac section but soon grew to include radio news, radio jobs (page 3) and other radio-related articles.