Return of the Wandering Verse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Role of Translation in Comparative Literature

Role of Translation in Comparative Literature Surjeet Singh Warwal Abstract In today’s world Translation is getting more and more popularity. There are many reasons behind it. The first and the foremost reason is that it contributes to the unity of nations. It also encourages mutual understanding, broad-mindedness, cultural dialogues and intertextuality. But one can hardly think of comparative literature without immediate thinking of translation. For instance most readers in India know the works of Goethe, Tolstoy, Balzac, Shakespeare and Gorky only through translation. It is through the intermediary of translator that we get access to other literatures. Thus Comparative Literature and translation humanize relationship between people and nations. As an intermediary between languages, thoughts and cultures, they contribute to the respect of difference and alterability. Moreover, they unite the self and the other in their truths, myths, force and weakness. From a historical perspective, comparative literature and translation have always been complementary. Without the help of translation a normal person, who usually knows two to three languages would never have known the universal masterpieces of Dante, Shakespeare, Borges, Kalidas, and Cervantes etc. A normal person usually may not know more than two-three languages. But if s/he wanted to study and compare the literature of two or more languages s/he must be familiar with those languages and cultures. If s/he does not know any of these languages s/he can take help of translation. Those texts might be translated by someone else who knows that language and the comparativist can use that translated text to solve his/her purpose. -

NATIONAL AWARDS JNANPITH AWARD Year Name Language

NATIONAL AWARDS JNANPITH AWARD he Jnanpith Award, instituted on May 22, 1961, is given for the best creative literary T writing by any Indian citizen in any of the languages included in the VIII schedule of the Constitution of India. From 1982 the award is being given for overall contribution to literature. The award carries a cash price of Rs 2.5 lakh, a citation and a bronze replica of Vagdevi. The first award was given in 1965 . Year Name Language Name of the Work 1965 Shankara Kurup Malayalam Odakkuzhal 1966 Tara Shankar Bandopadhyaya Bengali Ganadevta 1967 Dr. K.V. Puttappa Kannada Sri Ramayana Darshan 1967 Uma Shankar Joshi Gujarati Nishitha 1968 Sumitra Nandan Pant Hindi Chidambara 1969 Firaq Garakpuri Urdu Gul-e-Naghma 1970 Viswanadha Satyanarayana Telugu Ramayana Kalpavrikshamu 1971 Bishnu Dey Bengali Smriti Satta Bhavishyat 1972 Ramdhari Singh Dinakar Hindi Uravasi 1973 Dattatreya Ramachandran Kannada Nakutanti Bendre 1973 Gopinath Mohanty Oriya Mattimatal 1974 Vishnu Sankaram Khanldekar Marathi Yayati 1975 P.V. Akhilandam Tamil Chittrappavai 1976 Asha Purna Devi Bengali Pratham Pratisruti 1977 Kota Shivarama Karanth Kannada Mukajjiya Kanasugalu 1978 S.H. Ajneya Hindi Kitni Navon mein Kitni Bar 1979 Birendra Kumar Bhattacharya Assamese Mrityunjay 1980 S.K. Pottekkat Malayalam Oru Desattinte Katha 1981 Mrs. Amrita Pritam Punjabi Kagaz te Canvas 1982 Mahadevi Varma Hindi Yama 1983 Masti Venkatesa Iyengar Kannada Chikka Veera Rajendra 1984 Takazhi Siva Shankar Pillai Malayalam 1985 Pannalal Patel Gujarati 1986 Sachidanand Rout Roy Oriya 1987 Vishnu Vaman Shirwadkar Kusumagraj 1988 Dr. C. Narayana Reddy Telugu Vishwambhara 1989 Qurratulain Hyder Urdu 1990 Prof. Vinayak Kishan Gokak Kannada Bharatha Sindhu Rashmi Year Name Language Name of the Work 1991 Subhas Mukhopadhyay Bengali 1992 Naresh Mehta Hindi 1993 Sitakant Mohapatra Oriya 1994 Prof. -

E-Newsletter

DELHI Bhasha Samman Presentation hasha Samman for 2012 were presidential address. Ampareen Lyngdoh, Bconferred upon Narayan Chandra Hon’ble Miniser, was the chief guest and Goswami and Hasu Yasnik for Classical Sylvanus Lamare, as the guest of honour. and Medieval Literature, Sondar Sing K Sreenivasarao in in his welcome Majaw for Khasi literature, Addanda C address stated that Sahitya Akademi is Cariappa and late Mandeera Jaya committed to literatures of officially Appanna for Kodava and Tabu Ram recognized languages has realized that Taid for Mising. the literary treasures outside these Akademi felt that while The Sahitya Akademi Bhasha languages are no less invaluable and no it was necessary to Samman Presentation Ceremony and less worthy of celebration. Hence Bhasha continue to encourage Awardees’ Meet were held on 13 May Samman award was instituted to honour writers and scholars in 2013 at the Soso Tham Auditorium, writers and scholars. Sahitya Akademi languages not formally Shillong wherein the Meghalaya Minister has already published quite a number recognised by the of Urban Affairs, Ampareen Lyngdoh of translations of classics from our Akademi, it therefore, was the chief guest. K Sreenivasarao, bhashas. instituted Bhasha Secretary, Sahitya Akademi delivered the He further said, besides the Samman in 1996 to welcome address. President of Sahitya conferment of sammans every year for be given to writers, Akademi, Vishwanath Prasad Tiwari scholars who have explored enduring scholars, editors, presented the Samman and delivered his significance of medieval literatures to lexicographers, collectors, performers or translators. This Samman include scholars who have done valuable contribution in the field of classical and medieval literature. -

Wandering Writers in the Himalaya: Contesting Narratives and Renunciation in Modern Hindi Literature

Cracow Indological Studies vol. XVII (2015) 10.12797/CIS.17.2015.17.04 Nicola Pozza [email protected] (University of Lausanne, Switzerland) Wandering Writers in the Himalaya: Contesting Narratives and Renunciation in Modern Hindi Literature Summary: The Himalayan setting—especially present-day Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand—has fascinated many a writer in India. Journeys, wanderings, and sojourns in the Himalaya by Hindi authors have resulted in many travelogues, as well as in some emblematic short stories of modern Hindi literature. If the environment of the Himalaya and its hill stations has inspired the plot of several fictional writ- ings, the description of the life and traditions of its inhabitants has not been the main focus of these stories. Rather, the Himalayan setting has primarily been used as a nar- rative device to explore and contest the relationship between the mountain world and the intrusive presence of the external world (primarily British colonialism, but also patriarchal Hindu society). Moreover, and despite the anti-conformist approach of the writers selected for this paper (Agyeya, Mohan Rakesh, Nirmal Verma and Krishna Sobti), what mainly emerges from an analysis of their stories is that the Himalayan setting, no matter the way it is described, remains first and foremost a lasting topos for renunciation and liberation. KEYWORDS: Himalaya, Hindi, fiction, wandering, colonialism, modernity, renunci- ation, Agyeya, Nirmal Verma, Mohan Rakesh, Krishna Sobti. Introduction: Himalaya at a glance The Himalaya has been a place of fascination for non-residents since time immemorial and has attracted travellers, monks and pilgrims and itinerant merchants from all over Asia and Europe. -

Theoretical and Literary Spaces in Bangladesh Amitava

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Prometheus-Academic Collections The Marginalized in the Construction of ‘Indigenous’ Theoretical and Literary Spaces in Bangladesh Amitava CHAKRABORTY (Tokyo University of Foreign Studies, Japan) 1㸬 In the middle of the 80s of the last Century, Bengali culture witnessed the emergence of a literary and theoretical movement known as ‘Uttaradhunikatabad’1. The movement was initiated by poet and critic Amitabha Gupta, who in 1985 presented the concept in the little magazine Janapada. It was then nurtured by critics, literary theoreticians and litterateurs like Anjan Sen, Birendra Chakravarti, Uday Narayan Singha, Tapodhir Bhattacharjee etc. from India and Ezaz Yusufi, Sajidul Haq, Jillur Rahman and Khondakar Ashraf Hossain from Bangladesh. Little magazines from India and Bangladesh like Gangeya Patra, Beej, Alochanachakra, Samprata, Lalnakkhatra, Chatimtala, Sanket, Anyastar, Drastabya, Bipratik, Sudarshanchakra, 1400, Ekabingsho etc. nurtured the movement. When Gupta first proposed the concept, it was centered on a new trend in poetry, which Gupta identified as a move beyond modernist literary culture. Following years, however, saw the movement developing its’ unique corpus of theoretical postulations regarding poetry and other forms of literature, poetic language and ontology. Gupta’s article titled Nibedan, published as the appendix of an anthology of Uttaradhunik poems, titled Uttar Adhunik Kabita2, offers a comprehensive account of the theoretical understanding at its earliest phase. He posited the new movement against the Modernist 1 Uttar = Beyond, Adhunikatabad = Modernism. (Adhunik= Modern, Adhunikata= Modernity) Uttar is also used to mean ‘Post’ which has led many scholars and thinkers in translating this term as ‘Postmodernism’, whereas a few others have used the term Uttaradhunikatabad as one of the translations of the term ‘Postmodernism’. -

India Progressive Writers Association; *7:Arxicm

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 124 936 CS 202 742 ccpp-.1a, CsIrlo. Ed. Marxist Influences and South Asaan li-oerazure.South ;:sia Series OcasioLal raper No. 23,Vol. I. Michijar East Lansing. As:,an Studies Center. PUB rAIE -74 NCIE 414. 7ESF ME-$C.8' HC-$11.37 Pius ?cstage. 22SCrIP:0:", *Asian Stud,es; 3engali; *Conference reports; ,,Fiction; Hindi; *Literary Analysis;Literary Genres; = L_tera-y Tnfluences;*Literature; Poetry; Feal,_sm; *Socialism; Urlu All India Progressive Writers Association; *7:arxicm 'ALZT:AL: Ti.'__ locument prasen-ls papers sealing *viithvarious aspects of !',arxi=it 2--= racyinfluence, and more specifically socialisr al sr, ir inlia, Pakistan, "nd Bangladesh.'Included are articles that deal with _Aich subjects a:.the All-India Progressive Associa-lion, creative writers in Urdu,Bengali poets today Inclian poetry iT and socialist realism, socialist real.Lsm anu the Inlion nov-,-1 in English, the novelistMulk raj Anand, the poet Jhaverchan'l Meyhani, aspects of the socialistrealist verse of Sandaram and mash:: }tar Yoshi, *socialistrealism and Hindi novels, socialist realism i: modern pos=y, Mohan Bakesh andsocialist realism, lashpol from tealist to hcmanisc. (72) y..1,**,,A4-1.--*****=*,,,,k**-.4-**--4.*x..******************.=%.****** acg.u.re:1 by 7..-IC include many informalunpublished :Dt ,Ivillable from othr source r.LrIC make::3-4(.--._y effort 'c obtain 1,( ,t c-;;,y ava:lable.fev,?r-rfeless, items of marginal * are oft =.ncolntered and this affects the quality * * -n- a%I rt-irodu::tior:; i:";IC makes availahl 1: not quali-y o: th< original document.reproductiour, ba, made from the original. -

MA BENGALI SYLLABUS 2015-2020 Department Of

M.A. BENGALI SYLLABUS 2015-2020 Department of Bengali, Bhasa Bhavana Visva Bharati, Santiniketan Total No- 800 Total Course No- 16 Marks of Per Course- 50 SEMESTER- 1 Objective : To impart knowledge and to enable the understanding of the nuances of the Bengali literature in the social, cultural and political context Outcome: i) Mastery over Bengali Literature in the social, cultural and political context ii) Generate employability Course- I History of Bengali Literature (‘Charyapad’ to Pre-Fort William period) An analysis of the literature in the social, cultural and political context The Background of Bengali Literature: Unit-1 Anthologies of 10-12th century poetry and Joydev: Gathasaptashati, Prakitpoingal, Suvasito Ratnakosh Bengali Literature of 10-15thcentury: Charyapad, Shrikrishnakirtan Literature by Translation: Krittibas, Maladhar Basu Mangalkavya: Biprodas Pipilai Baishnava Literature: Bidyapati, Chandidas Unit-2 Bengali Literature of 16-17th century Literature on Biography: Brindabandas, Lochandas, Jayananda, Krishnadas Kabiraj Baishnava Literature: Gayanadas, Balaramdas, Gobindadas Mangalkabya: Ketakadas, Mukunda Chakraborty, Rupram Chakraborty Ballad: Maymansinghagitika Literature by Translation: Literature of Arakan Court, Kashiram Das [This Unit corresponds with the Syllabus of WBCS Paper I Section B a)b)c) ] Unit-3 Bengali Literature of 18th century Mangalkavya: Ghanaram Chakraborty, Bharatchandra Nath Literature Shakta Poetry: Ramprasad, Kamalakanta Collection of Poetry: Khanadagitchintamani, Padakalpataru, Padamritasamudra -

Jnanpith Award * *

TRY -- TRUE -- TRUST NUMBER ONE SITE FOR COMPETITIVE EXAM SELF LEARNING AT ANY TIME ANY WHERE * * Jnanpith Award * * The Jnanpith Award (also spelled as Gyanpeeth Award ) is an Indian literary award presented annually by the Bharatiya Jnanpith to an author for their "outstanding contribution towards literature". Instituted in 1961, the award is bestowed only on Indian writers writing in Indian languages included in the Eighth Schedule to the Constitution of India and English Year Recipient(s) Language(s) 1965 G. Sankara Kurup Malayalam 1966 Tarasankar Bandyopadhyay Bengali Kuppali Venkatappa Puttappa Kannada 1967 Umashankar Joshi Gujarati 1968 Sumitranandan Pant Hindi 1969 Firaq Gorakhpuri Urdu 1970 Viswanatha Satyanarayana Telugu 1971 Bishnu Dey Bengali 1972 Ramdhari Singh Dinkar Hindi Dattatreya Ramachandra Bendre Kannada 1973 Gopinath Mohanty Oriya 1974 Vishnu Sakharam Khandekar Marathi 1975 P. V. Akilan Tamil 1976 Ashapoorna Devi Bengali 1977 K. Shivaram Karanth Kannada 1978 Sachchidananda Vatsyayan Hindi 1979 Birendra Kumar Bhattacharya Assamese 1980 S. K. Pottekkatt Malayalam 1981 Amrita Pritam Punjabi 1982 Mahadevi Varma Hindi 1983 Masti Venkatesha Iyengar Kannada 1984 Thakazhi Sivasankara Pillai Malayalam 1985 Pannalal Patel Gujarati www.sirssolutions.in 91+9830842272 Email: [email protected] Please Post Your Comment at Our Website PAGE And our Sirs Solutions Face book Page Page 1 of 2 TRY -- TRUE -- TRUST NUMBER ONE SITE FOR COMPETITIVE EXAM SELF LEARNING AT ANY TIME ANY WHERE * * Jnanpith Award * * Year Recipient(s) Language(s) 1986 Sachidananda Routray Oriya 1987 Vishnu Vaman Shirwadkar (Kusumagraj) Marathi 1988 C. Narayanareddy Telugu 1989 Qurratulain Hyder Urdu 1990 V. K. Gokak Kannada 1991 Subhas Mukhopadhyay Bengali 1992 Naresh Mehta Hindi 1993 Sitakant Mahapatra Oriya 1994 U. -

DU MA Comparative Indian Literature

DU MA Comparative Indian Literature Topic:‐ CIL MA S2 1) ‘Kavirajamarga' was written in: [Question ID = 5641] 1. Kannada [Option ID = 22558] 2. Hindi [Option ID = 22559] 3. Sanskrit [Option ID = 22560] 4. Bengali [Option ID = 22561] Correct Answer :‐ Kannada [Option ID = 22558] 2) ‘Jnaneswari' is a commentary on: [Question ID = 5642] 1. Gita [Option ID = 22562] 2. Astadhyayi [Option ID = 22563] 3. Natyashastra [Option ID = 22564] 4. Arthashastra [Option ID = 22565] Correct Answer :‐ Gita [Option ID = 22562] 3) Madhava Kandali wrote in: [Question ID = 5643] 1. Tamil [Option ID = 22566] 2. Urdu [Option ID = 22567] 3. Bengali [Option ID = 22568] 4. Assamese [Option ID = 22569] Correct Answer :‐ Assamese [Option ID = 22569] 4) Baba Farid wrote in: [Question ID = 5644] 1. Punjabi [Option ID = 22570] 2. Urdu [Option ID = 22571] 3. Bengali [Option ID = 22572] 4. Sindhi [Option ID = 22573] Correct Answer :‐ Punjabi [Option ID = 22570] 5) Which of the following is considered the only tragedy in Sanskrit literature: [Question ID = 5645] 1. Mricchakatika [Option ID = 22574] 2. Balacharita [Option ID = 22575] 3. Urubhanga [Option ID = 22576] 4. Abhijnanasakuntalam [Option ID = 22577] Correct Answer :‐ Urubhanga [Option ID = 22576] 6) ‘Gitagovindam' was written in: [Question ID = 5646] 1. Kannada [Option ID = 22578] 2. Prakrit [Option ID = 22579] 3. Sanskrit [Option ID = 22580] 4. Hindi [Option ID = 22581] Correct Answer :‐ Sanskrit [Option ID = 22580] 7) 'Rani Ketki Ki Kahani' was written by: [Question ID = 5647] 1. Insha Allah Khan [Option ID = 22582] 2. V. Venkatachapathy [Option ID = 22583] 3. Firaq Gorakhpuri [Option ID = 22584] 4. Bishnu Dey [Option ID = 22585] Correct Answer :‐ Insha Allah Khan [Option ID = 22582] 8) The College of Fort William was established in: [Question ID = 5648] 1. -

Jnanpith Award

Jnanpith Award JNANPITH AWARD The Jnanpith Award is an Indian literary award presented annually by the Bharatiya Jnanpith to an author for their "outstanding contribution towards literature". Instituted in 1961, the award is bestowed only on Indian writers writing in Indian languages included in the Eighth Schedule to the Constitution of India and English, with no posthumous conferral. The Bharatiya Jnanpith, a research and cultural institute founded in 1944 by industrialist Sahu Shanti Prasad Jain, conceived an idea in May 1961 to start a scheme "commanding national prestige and of international standard" to "select the best book out of the publications in Indian languages". The first recipient of the award was the Malayalam writer G. Sankara Kurup who received the award in 1965 for his collection of poems, Odakkuzhal (The Bamboo Flute), published in 1950. In 1976, Bengali novelist Ashapoorna Devi became the first woman to win the award and was honoured for the 1965 novel Pratham Pratisruti (The First Promise), the first in a trilogy. Year Recipient(s) Language(s) 1965 G. Sankara Kurup Malayalam (1st) 1966 Tarasankar Bandyopadhyay Bengali (2nd) 1967 Umashankar Joshi Gujarati (3rd) 1967 Kuppali Venkatappa Puttappa 'Kuvempu' Kannada (3rd) 1 Download Study Materials on www.examsdaily.in Follow us on FB for exam Updates: ExamsDaily Jnanpith Award 1968 Sumitranandan Pant Hindi (4th) 1969 Firaq Gorakhpuri Urdu (5th) 1970 Viswanatha Satyanarayana Telugu (6th) 1971 Bishnu Dey Bengali (7th) 1972 Ramdhari Singh 'Dinkar' Hindi (8th) 1973 D. R. Bendre Kannada (9th) 1973 Gopinath Mohanty Odia (9th) 1974 Vishnu Sakharam Khandekar Marathi (10th) 1975 Akilan Tamil (11th) 1976 Ashapoorna Devi Bengali (12th) 1977 K. -

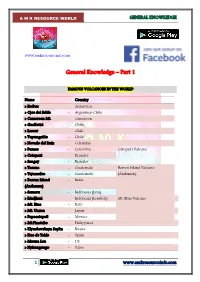

General Knowledge

A M K RESOURCE WORLD GENERAL KNOWLEDGE www.amkresourceinfo.com General Knowledge – Part 1 FAMOUS VOLCANOES IN THE WORLD Name Country » Erebus - Antarctica » Ojos dei Saldo - Argentina-Chile » Cameroon Mt. - Cameroon » Guallatiri - Chile » Lascar - Chile » Tupungatito - Chile » Nevado del Ruiz - Colombia » Purace - Colombia Cotopaxi Valcano » Cotopaxi - Ecuador » Sangay - Ecuador » Tacana - Guatemala Barren Island Valcano » Tajumulco - Guatemala (Andaman) » Barren Island - India (Andaman) » Semeru - Indonesia (Java) » Rindjiani - Indonesia (Lombok) Mt. Etna Valcano » Mt. Etna - Italy » Mt. Unzen - Japan » Popocatepetl - Mexico » Mt.Pinatubo - Philippines » Klyuchevskaya Sopka - Russia » Pico de Teide - Spain » Mauna Loa - US » Nyirangongo - Zaire 1 www.amkresourceinfo.com A M K RESOURCE WORLD GENERAL KNOWLEDGE CHANGED NAMES Previous Name Changed Name Abyssinia Ethiopia Batavia Djakarta Basutoland Lesotho Bechuanaland Botswana Burma Myanmar Christina Oslo Constantinople Istanbul Dacca Dhaka Dutch East Indies Indonesia Ceylon Sri Lanka East Timor Loro Sae Egypt United Arab Rep Formosa Taiwan Gold Coast Ghana Holland The Netherlands Nippon Japan Leopoldville Kinshasa Mesopotamia Iraq Northern Rhodesia Zambia Peking Bejing Persia Iran Rangoon Yangon Rhodesia Zimbabwe Siam Thailand South West Africa Namibia FIRST WOMEN ● Prime-Minister—Indira Gandhi ● Woman (India and World) who crossed English Channel through Swimming—Arti Shah ● Governor—Sarojini Naidu (U. P.) ● I. P. S.—Kiran Bedi ● President of National Congress—Anne Besant ● Chairman of -

Department of Comparative Indian Language and Literature (CILL) CSR

Department of Comparative Indian Language and Literature (CILL) CSR 1. Title and Commencement: 1.1 These Regulations shall be called THE REGULATIONS FOR SEMESTERISED M.A. in Comparative Indian Language and Literature Post- Graduate Programme (CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM) 2018, UNIVERSITY OF CALCUTTA. 1.2 These Regulations shall come into force with effect from the academic session 2018-2019. 2. Duration of the Programme: The 2-year M.A. programme shall be for a minimum duration of Four (04) consecutive semesters of six months each/ i.e., two (2) years and will start ordinarily in the month of July of each year. 3. Applicability of the New Regulations: These new regulations shall be applicable to: a) The students taking admission to the M.A. Course in the academic session 2018-19 b) The students admitted in earlier sessions but did not enrol for M.A. Part I Examinations up to 2018 c) The students admitted in earlier sessions and enrolled for Part I Examinations but did not appear in Part I Examinations up to 2018. d) The students admitted in earlier sessions and appeared in M.A. Part I Examinations in 2018 or earlier shall continue to be guided by the existing Regulations of Annual System. 4. Attendance 4.1 A student attending at least 75% of the total number of classes* held shall be allowed to sit for the concerned Semester Examinations subject to fulfilment of other conditions laid down in the regulations. 4.2 A student attending at least 60% but less than 75% of the total number of classes* held shall be allowed to sit for the concerned Semester Examinations subject to the payment of prescribed condonation fees and fulfilment of other conditions laid down in the regulations.