Viewing the Historical Development of Traditional Concepts of Form in the Theatre, and by Indicating the Point of Emergence of the New Kind

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Eccentricities of a Nightingale by Tennessee Williams

The Eccentricities of a Nightingale by Tennessee Williams April 9-25 AUDIENCE GUIDE Compiled, Written and Edited by Jack Marshall About The American Century Theater The American Century Theater was founded in 1994. We are a professional company dedicated to presenting great, important, and neglected American dramatic works of the Twentieth Century… what Henry Luce called “the American Century.” The company’s mission is one of rediscovery, enlightenment, and perspective, not nostalgia or preservation. Americans must not lose the extraordinary vision and wisdom of past artists, nor can we afford to lose our mooring to our shared cultural heritage. Our mission is also driven by a conviction that communities need theater, and theater needs audiences. To those ends, this company is committed to producing plays that challenge and move all citizens, of all ages and all points of view. These Audience Guides are part of our effort to enhance the appreciation of these works, so rich in history, content, and grist for debate. Like everything we do to keep alive and vital the great stage works of the Twentieth Century, these study guides are made possible in great part by the support of Arlington County’s Cultural Affairs Division and the Virginia Commission for the Arts. 2 Table of Contents The Playwright 444 Comparing Summer and Smoke 7 And The Eccentricities of a Nightingale By Richard Kramer “I am Widely Regarded…” 12 By Tennessee Wiliams Prostitutes in American Drama 13 The Show Must Go On 16 By Jack Marshall The Works of Tennessee Williams 21 3 The Playwright: Tennessee Williams [The following biography was originally written for Williams when he was a Kennedy Center Honoree in 1979] His craftsmanship and vision marked Tennessee Williams as one of the most talented playwrights in contemporary theater. -

A Transcultural Perspective on the Casting of the Rose Tattoo

RSA JOU R N A L 25/2014 GIULIANA MUS C IO A Transcultural Perspective on the Casting of The Rose Tattoo A transcultural perspective on the film The Rose Tattoo (Daniel Mann, 1955), written by Tennessee Williams, is motivated by its setting in an Italian-American community (specifically Sicilian) in Louisiana, and by its cast, which includes relevant Italian participation. A re-examination of its production and textuality illuminates not only Williams’ work but also the cultural interactions between Italy and the U.S. On the background, the popularity and critical appreciation of neorealist cinema.1 The production of the film The Rose Tattoo has a complicated history, which is worth recalling, in order to capture its peculiar transcultural implications in Williams’ own work, moving from some biographical elements. In the late 1940s Tennessee Williams was often traveling in Italy, and visited Sicily, invited by Luchino Visconti (who had directed The Glass Managerie in Rome, in 1946) for the shooting of La terra trema (1948), where he went with his partner Frank Merlo, an occasional actor of Sicilian origins (Williams, Notebooks 472). Thus his Italian experiences involved both his professional life, putting him in touch with the lively world of Italian postwar theater and film, and his affections, with new encounters and new friends. In the early 1950s Williams wrote The Rose Tattoo as a play for Anna Magnani, protagonist of the neorealist masterpiece Rome Open City (Roberto Rossellini, 1945). However, the Italian actress was not yet comfortable with acting in English and therefore the American stage version (1951) starred Maureen Stapleton instead and Method actor Eli Wallach. -

Finding Aid for the Bouchard Collection (MUM00041)

University of Mississippi eGrove Archives & Special Collections: Finding Aids Library November 2020 Finding Aid for the Bouchard Collection (MUM00041) Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/finding_aids Recommended Citation Bouchard Collection (MUM00041), Department of Archives and Special Collections, J.D. Williams Library, University of Mississippi This Finding Aid is brought to you for free and open access by the Library at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Archives & Special Collections: Finding Aids by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Mississippi Libraries Bouchard Collection MUM00041 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY INFORMATION Summary Information Repository University of Mississippi Libraries Scope and Contents note Title Administrative Information Bouchard Collection Controlled Access Headings ID Collection Inventory MUM00041 Special Collections Map Case Drawer 1 Date [inclusive] 1949-1999 Special Collections Map Case Drawer 2 Extent Special Collections Map 4.0 Linear feet Case Drawer 3 Box 1 Preferred Citation Box 2 Bouchard Collection (MUM00041), Department of Archives and Special Collections, J.D. Williams Library, University of Mississippi Return to Table of Contents » SCOPE AND CONTENTS NOTE Mississippi film related items including posters, lobby cards, film stills, publicity books, etc. Return to Table of Contents » ADMINISTRATIVE INFORMATION Publication Information University of Mississippi Libraries Revision Description Revised by Lauren Rogers. 2016 Access Restrictions Open Copyright Restrictions The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. -

The 200 Plays That Every Theatre Major Should Read

The 200 Plays That Every Theatre Major Should Read Aeschylus The Persians (472 BC) McCullers A Member of the Wedding The Orestia (458 BC) (1946) Prometheus Bound (456 BC) Miller Death of a Salesman (1949) Sophocles Antigone (442 BC) The Crucible (1953) Oedipus Rex (426 BC) A View From the Bridge (1955) Oedipus at Colonus (406 BC) The Price (1968) Euripdes Medea (431 BC) Ionesco The Bald Soprano (1950) Electra (417 BC) Rhinoceros (1960) The Trojan Women (415 BC) Inge Picnic (1953) The Bacchae (408 BC) Bus Stop (1955) Aristophanes The Birds (414 BC) Beckett Waiting for Godot (1953) Lysistrata (412 BC) Endgame (1957) The Frogs (405 BC) Osborne Look Back in Anger (1956) Plautus The Twin Menaechmi (195 BC) Frings Look Homeward Angel (1957) Terence The Brothers (160 BC) Pinter The Birthday Party (1958) Anonymous The Wakefield Creation The Homecoming (1965) (1350-1450) Hansberry A Raisin in the Sun (1959) Anonymous The Second Shepherd’s Play Weiss Marat/Sade (1959) (1350- 1450) Albee Zoo Story (1960 ) Anonymous Everyman (1500) Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf Machiavelli The Mandrake (1520) (1962) Udall Ralph Roister Doister Three Tall Women (1994) (1550-1553) Bolt A Man for All Seasons (1960) Stevenson Gammer Gurton’s Needle Orton What the Butler Saw (1969) (1552-1563) Marcus The Killing of Sister George Kyd The Spanish Tragedy (1586) (1965) Shakespeare Entire Collection of Plays Simon The Odd Couple (1965) Marlowe Dr. Faustus (1588) Brighton Beach Memoirs (1984 Jonson Volpone (1606) Biloxi Blues (1985) The Alchemist (1610) Broadway Bound (1986) -

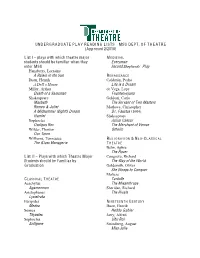

Undergraduate Play Reading List

UND E R G R A DU A T E PL A Y R E A DIN G L ISTS ± MSU D EPT. O F T H E A T R E (Approved 2/2010) List I ± plays with which theatre major M E DI E V A L students should be familiar when they Everyman enter MSU Second 6KHSKHUGV¶ Play Hansberry, Lorraine A Raisin in the Sun R E N A ISSA N C E Ibsen, Henrik Calderón, Pedro $'ROO¶V+RXVH Life is a Dream Miller, Arthur de Vega, Lope Death of a Salesman Fuenteovejuna Shakespeare Goldoni, Carlo Macbeth The Servant of Two Masters Romeo & Juliet Marlowe, Christopher A Midsummer Night's Dream Dr. Faustus (1604) Hamlet Shakespeare Sophocles Julius Caesar Oedipus Rex The Merchant of Venice Wilder, Thorton Othello Our Town Williams, Tennessee R EST O R A T I O N & N E O-C L ASSI C A L The Glass Menagerie T H E A T R E Behn, Aphra The Rover List II ± Plays with which Theatre Major Congreve, Richard Students should be Familiar by The Way of the World G raduation Goldsmith, Oliver She Stoops to Conquer Moliere C L ASSI C A L T H E A T R E Tartuffe Aeschylus The Misanthrope Agamemnon Sheridan, Richard Aristophanes The Rivals Lysistrata Euripides NIN E T E E N T H C E N T UR Y Medea Ibsen, Henrik Seneca Hedda Gabler Thyestes Jarry, Alfred Sophocles Ubu Roi Antigone Strindberg, August Miss Julie NIN E T E E N T H C E N T UR Y (C O N T.) Sartre, Jean Shaw, George Bernard No Exit Pygmalion Major Barbara 20T H C E N T UR Y ± M ID C E N T UR Y 0UV:DUUHQ¶V3rofession Albee, Edward Stone, John Augustus The Zoo Story Metamora :KR¶V$IUDLGRI9LUJLQLD:RROI" Beckett, Samuel E A R L Y 20T H C E N T UR Y Waiting for Godot Glaspell, Susan Endgame The Verge Genet Jean The Verge Treadwell, Sophie The Maids Machinal Ionesco, Eugene Chekhov, Anton The Bald Soprano The Cherry Orchard Miller, Arthur Coward, Noel The Crucible Blithe Spirit All My Sons Feydeau, Georges Williams, Tennessee A Flea in her Ear A Streetcar Named Desire Synge, J.M. -

The Rise of Controversial Content in Film

The Climb of Controversial Film Content by Ashley Haygood Submitted to the Department of Communication Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in Communication at Liberty University May 2007 Film Content ii Abstract This study looks at the change in controversial content in films during the 20th century. Original films made prior to 1968 and their remakes produced after were compared in the content areas of profanity, nudity, sexual content, alcohol and drug use, and violence. The advent of television, post-war effects and a proposed “Hollywood elite” are discussed as possible causes for the increase in controversial content. Commentary from industry professionals on the change in content is presented, along with an overview of American culture and the history of the film industry. Key words: film content, controversial content, film history, Hollywood, film industry, film remakes i. Film Content iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my family for their unwavering support during the last three years. Without their help and encouragement, I would not have made it through this program. I would also like to thank the professors of the Communications Department from whom I have learned skills and information that I will take with me into a life-long career in communications. Lastly, I would like to thank my wonderful Thesis committee, especially Dr. Kelly who has shown me great patience during this process. I have only grown as a scholar from this experience. ii. Film Content iv Table of Contents ii. Abstract iii. Acknowledgements I. Introduction ……………………………………………………………………1 II. Review of the Literature……………………………………………………….8 a. -

Seattle Repertory Theatre Records Inventory Accession No: 1481-007

UN IVERSITY U BRARIES w UNIVERSITY of WASHI NGTON Spe ial Colle tions. Seattle Repertory Theatre records Inventory Accession No: 1481-007 Special Collections Division University of Washington Libraries Box 352900 Seattle, Washington, 98195-2900 USA (206) 543-1929 This document forms part of the Preliminary Guide to the Seattle Repertory Theatre Records. To find out more about the history, context, arrangement, availability and restrictions on this collection, click on the following link: http://digital.lib.washington.edu/findingaids/permalink/SeattleRepertoryTheatre1481/ Special Collections home page: http://www.lib.washington.edu/specialcollections/ Search Collection Guides: http://digital.lib.washington.edu/findingaids/search SEATTLE REPERTORY THEATRE CONTAINER LIST Acc. No. 1481-7 INCL. BOX PaODUCTION BOOKS DATES 1 Day, Clarence.· Life with Father 12/8/74 - 1/2/75 Ibsen, Henrik. Poll's House 2/2 - 2/27/75 Stoppard, Tom. After Magritte/The Real Inspector Hound 3/11/- 4/12/75 Melfi, Leonard. Lunchtime/Halloween 4/21 - 5/19/75 Jones, Preston. The Last of the Knight of 1/11 - 2/5/76 the White Magnolia Lowell, Robert. Benito Cereno 2/24 - 3/7 /76 Orton, Joe. Entertaining Mr. Sloan 3/13 - 3/28/76 Made for T.V. (media improvisation) 4/3 - 4/18/76 Patrick, Robert. Kennedy's Children 4/24 - 5/9/76 Ondaatje, Michael. Billy the Kid 5/15 - 5/30/76 2 O'Neill, Eugene.· Anna Christie 11/4 - 12/9/76 Christie, Agatha·.. The Mousetrap 12/12/76 - 1/6/77 Arbuzov, Aleksei_ Once Upon a Time ca. 1/77 Williams, Tennessee. Cat on a Hot Tin Roof 1/9 - 1/23/77 Bond, Edward. -

Anniversary Season

th ASOLO REPERTORY THEATRE o ANNIVERSARY6 SEASON ASOLO REPERTORY THEATRE th 6oANNIVERSARY DINNER November 26, 2018 The Westin | Sarasota 6pm | Cocktail Reception 7pm | Dinner, Presentation and Award Ceremony • Vic Meyrich Tech Award • Bradford Wallace Acting Award 03 HONOREES Honoring 12 artists who made an indelible impact on the first decade and beyond. 04-05 WELCOME LETTER 06-11 60 YEARS OF HISTORY 12-23 HONOREE INTERVIEWS 24-27 LIST OF PRODUCTIONS From 1959 through today rep 31 TRIBUTES o l aso HONOREES Steve Hogan Assistant Technical Director, 1969-1982 Master Carpenter, 1982-2001 Shop Foreman, 2001-Present Polly Holliday Resident Acting Company, 1962-1972 Vic Meyrich Technical Director, 1968-1992 Production Manager, 1992-2017 Production Manager & Operations Director, 2017-Present Howard Millman Actor, 1959 Managing Director, Stage Director, 1968-1980 Producing Artistic Director, 1995-2006 Stephanie Moss Resident Acting Company, 1969-1970 Assistant Stage Manager, 1972-1990 Bob Naismith Property Master, 1967-2000 Barbara Redmond Resident Acting Company, 1968-2011 Director, Playwright, 1996-2003 Acting Faculty/Head of Acting, FSU/Asolo Conservatory, 1998-2011 Sharon Spelman Resident Acting Company, 1968-1971 and 1996-2010 Eberle Thomas Director, Actor, Playwright, 1960-1966 rep Co-Artistic Director, 1966-1973 Director, Actor, Playwright, 1976-2007 Brad Wallace o Resident Acting Company, 1961-2008 l Marian Wallace Box Office Associate, 1967-1968 Stage Manager, 1968-1969 Production Stage Manager, 1969-2010 John M. Wilson Master Carpenter, 1969-1977 asolorep.org | 03 aso We are grateful you are here tonight to celebrate and support Asolo Rep — MDE/LDG PHOTO WHICH ONE ??? Nationally renowned, world-class theatre, made in Sarasota. -

William and Mary Theatre Main Stage Productions

WILLIAM AND MARY THEATRE MAIN STAGE PRODUCTIONS 1926-1927 1934-1935 1941-1942 The Goose Hangs High The Ghosts of Windsor Park Gas Light Arms and the Man Family Portrait 1927-1928 The Romantic Age The School for Husbands You and I The Jealous Wife Hedda Gabler Outward Bound 1935-1936 1942-1943 1928-1929 The Unattainable Thunder Rock The Enemy The Lying Valet The Male Animal The Taming of the Shrew The Cradle Song *Bach to Methuselah, Part I Candida Twelfth Night *Man of Destiny Squaring the Circle 1929-1930 1936-1937 The Mollusc Squaring the Circle 1943-1944 Anna Christie Death Takes a Holiday Papa is All Twelfth Night The Gondoliers The Patriots The Royal Family A Trip to Scarborough Tartuffe Noah Candida 1930-1931 Vergilian Pageant 1937-1938 1944-1945 The Importance of Being Earnest The Night of January Sixteenth Quality Street Just Suppose First Lady Juno and the Paycock The Merchant of Venice The Mikado Volpone Enter Madame Liliom Private Lives 1931-1932 1938-1939 1945-1946 Sun-Up Post Road Pygmalion Berkeley Square RUR Murder in the Cathedral John Ferguson The Pirates of Penzance Ladies in Retirement As You Like It Dear Brutus Too Many Husbands 1932-1933 1939-1940 1946-1947 Outward Bound The Inspector General Arsenic and Old Lace Holiday Kind Lady Arms and the Man The Recruiting Officer Our Town The Comedy of Errors Much Ado About Nothing Hay Fever Joan of Lorraine 1933-1934 1940-1941 1947-1948 Quality Street You Can’t Take It with You The Skin of Our Teeth Hotel Universe Night Must Fall Blithe Spirit The Swan Mary of Scotland MacBeth -

Artistic Director Rupert Goold Today Announces the Almeida Theatre’S New Season

Press release: Thursday 1 February Artistic Director Rupert Goold today announces the Almeida Theatre’s new season: • The world premiere of The Writer by Ella Hickson, directed by Blanche McIntyre. • A rare revival of Sophie Treadwell’s 1928 play Machinal, directed by Natalie Abrahami. • The UK premiere of Dance Nation, Clare Barron’s award-winning play, directed by Bijan Sheibani. • The first London run of £¥€$ (LIES) from acclaimed Belgian company Ontroerend Goed. Also announced today: • The return of the Almeida For Free festival taking place from 3 to 5 April during the run of Tennessee Williams’ Summer and Smoke. • The new cohort of eleven Resident Directors. Rupert Goold said today, “It is with enormous excitement that we announce our new season, featuring two premieres from immensely talented and ground-breaking writers, a rare UK revival of a seminal, pioneering American play, and an exhilarating interactive show from one of the most revolutionary theatre companies in Europe. “We start by welcoming back Ella Hickson, following her epic Oil in 2016, with new play The Writer, directed by Blanche McIntyre. Like Ella’s previous work, this is a hugely ambitious, deeply political play that consistently challenges what theatre can and should be. “Following The Writer, we are thrilled to present a timely revival of Sophie Treadwell’s masterpiece, Machinal, directed by Natalie Abrahami. Ninety years after it emerged from the American expressionist theatre scene and twenty-five years since its last London production, it remains strikingly resonant in its depiction of oppression, gender and power. “I first saw Belgian company Ontroerend Goed’s show £¥€$ (LIES) at the Edinburgh Fringe last year. -

The Glass Menagerie by TENNESSEE WILLIAMS Directed by JOSEPH HAJ PLAY GUIDE Inside

Wurtele Thrust Stage / Sept 14 – Oct 27, 2019 The Glass Menagerie by TENNESSEE WILLIAMS directed by JOSEPH HAJ PLAY GUIDE Inside THE PLAY Synopsis, Setting and Characters • 4 Responses to The Glass Menagerie • 5 THE PLAYWRIGHT About Tennessee Williams • 8 Tom Is Tom • 11 In Williams’ Own Words • 13 Responses to Williams • 15 CULTURAL CONTEXT St. Louis, Missouri • 18 "The Play Is Memory" • 21 People, Places and Things in the Play • 23 ADDITIONAL INFORMATION For Further Reading and Understanding • 26 Guthrie Theater Play Guide Copyright 2019 DRAMATURG Carla Steen GRAPHIC DESIGNER Akemi Graves CONTRIBUTOR Carla Steen EDITOR Johanna Buch Guthrie Theater, 818 South 2nd Street, Minneapolis, MN 55415 All rights reserved. With the exception of classroom use by ADMINISTRATION 612.225.6000 teachers and individual personal use, no part of this Play Guide may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic BOX OFFICE 612.377.2224 or 1.877.44.STAGE (toll-free) or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by an information storage and retrieval system, without permission in guthrietheater.org • Joseph Haj, artistic director writing from the publishers. Some materials published herein are written especially for our Guide. Others are reprinted by permission of their publishers. The Guthrie Theater receives support from the National The Guthrie creates transformative theater experiences that ignite the imagination, Endowment for the Arts. This activity is made possible in part by the Minnesota State Arts Board, through an appropriation stir the heart, open the mind and build community through the illumination of our by the Minnesota State Legislature. The Minnesota State Arts common humanity. -

RAYMOND HILL: Good Morning

Tape A Side 1 SARAH CANBY JACKSON: This is Sarah Canby Jackson with the Harris County Archives Oral History Program, January 24, 2008. I am interviewing Raymond Hill in Houston, Texas, concerning his knowledge of the Juvenile Probation Department, Judge Robert Lowry, Harris County politics and government and anything else he would like to add. Good morning, Raymond. RAYMOND HILL: Good morning. SARAH CANBY JACKSON: First of all, tell me about your parents.1 RAYMOND HILL: It’s hard for me to do that because it’s hard for anybody to believe a person could have parents as good as mine. I’ve been in a number of groups where the groups had to make disclosures about, you know, their parents and their childhood. I tell mine and they say, “What you really need is a reality check,” and “You couldn’t have had it so good.” I’ll just have to ask you to forgive me, they were wonderful. That would be the overarching generalism that I would make. My father and mother, I truly believe, were absolutely honest. I believe they were extraordinarily generous. I believe they were deeply motivated to do the right thing and to extend the blessings of their lives to as many people as they possibly could during their lifetimes. They were not interested in money, as such, or making money and people would ask, “Well, why did your Dad do this or your Mother do that?” always looking for some sort of an advantage. The fact is that 1 George A. Hill, Jr.