Zenobi! Open Fire!’ Okoye’S Yell Across the Voxmitter Dragged Her Back to the View on the Gun Imager

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pearl Jam Sacramento, California October 30, 2000 Mp3, Flac, Wma

Pearl Jam Sacramento, California October 30, 2000 mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Sacramento, California October 30, 2000 Country: US Released: 2001 Style: Alternative Rock, Grunge, Classic Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1978 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1593 mb WMA version RAR size: 1985 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 333 Other Formats: MP3 AUD DTS DMF MP2 AU APE Tracklist 1-1 Whipping 1-2 Insignificance 1-3 Animal 1-4 Last Exit 1-5 State Of Love And Trust 1-6 Given To Fly 1-7 Small Town 1-8 Tremor Christ 1-9 Even Flow 1-10 Daughter 1-11 Betterman 1-12 Jeremy 1-13 Light Years 1-14 Immortality 1-15 Do The Evolution 1-16 Brain Of J 2-1 RVM 2-2 Encore Break 2-3 Breakerfall 2-4 Corduroy 2-5 Last Kiss 2-6 The Kids Are Alright 2-7 Go 2-8 Yellow Ledbetter Companies, etc. Mastered At – RFI Mastering Credits Design Concept – J.A.* Design, Layout – Brad Klausen Engineer – John Burton Mixed By – Brett Eliason Notes No. 67 (of 72) of the 2000 Binaural Tour Official Bootleg series. Comes in a Cardboard Gatefold Sleeve. The barcode, label name and catalog# are not visible anywhere on the cover sleeve or discs. They were indicated only on the original sealing sticker. Manufactured in Carrollton, GA (USA). Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode (Scanned): 696998562622 Related Music albums to Sacramento, California October 30, 2000 by Pearl Jam Pearl Jam - October 09 2009, San Diego, CA Pearl Jam - Новая Фонотека В Кармане Pearl Jam - 19 6 00 - Hala Tivoli - Ljubljana, Slovenia Pearl Jam - New York, NY - July 8th 2003 Pearl Jam - Soldier Field Chicago, IL 7/11/95 Pearl Jam - Jones Beach, New York - August 24, 2000 Pearl Jam - St. -

AND HE BUILT a CROOKED HOUSE Robert Heinlein

NELSON FEB 1941 p®llKfP WM — Look out for a COLD . .watch your THROAT gargle ListerineQuick! A careless sneeze, or an explosive cough, can shoot after a Listerine gargle. Even one hour after, reduc- troublesome germs in your direction at mile-a- tions up to 80% in the number of surface germs minute speed. In case they invade the tissues of associated with colds and sore throat were noted. your throat, you may be in for throat irritation, a That is why, we believe, Listerine in the last nine cold—or worse. years has built up such an impressive test record If you have been thus exposed, better gargle against colds . why thousands of people gargle witli it at first hint a sore throat. with Listerine Antiseptic at your earliest oppor- the of cold or simple tunity . Listerine kills millions of thegerms on mouth Fewer and Milder Colds in Tests and throat surfaces known as "secondary invaders” These tests showed that those who gargled with . often helps render them powerless to invade Listerine twice a day had fewer colds, milder colds, the tissue and aggravate infection. Used early and and colds of shorter duration than those who did often, Listerine may head off a cold, or reduce the not gargle. And fewer sore throats, also. severity of one already started. So remember, if you have been exposed to others Amazing Germ Reductions in Tests suffering from colds, if you feel a cold coming on, Tests have shown germ reductions ranging to gargle Listerine quick.! on mouth and throat surfaces fifteen minutes Lambert Pharmacal Co., St. -

J. Frank Wilson

J. FRANK WILSON J. Frank was born December 11, 1941 in Lufkin, TX. In 1962 J. Frank Wilson, After Being Discharged From Goodfellow Air Force Base, Auditioned For The San Angelo Based Group "The Cavaliers" (Sid Holmes-Lewis Elliott-Bob Zeller-Ray Smith). J. Frank Would Then Be Discovered By Independent Record Producer Sonley Roush Who Had Booked The Band At The Blue Note Club (3rd and Birdwell St) In Big Spring, Texas In 1962. After Signing A 3 Year Manager's Contract With Sid Holmes, In 1963, Frank Took A Leave Of Absents. In 1964 J. Frank Was Re-Instated As The Lead Singer For The Cavaliers Replacing John Maberry. The Cavaliers, J. Frank Wilson, Buddy Croyle, Lewis Elliott, Roland Atkinson, Jim Wynne And A Girl Who Sang In Church (unknown) Went About The Business Of Copying Wayne Cochran's Record In Ron Newdoll's Studio In San Angelo. With J. Frank In Top Form The Record (First Released On Tamara 761 & Le Cam 722) On Josie Started Moving Up The Billboard Charts. It Wasn't Long After This That Contract Disputes, Law Suits, And Greedy Un- Scrupulous Promoters Began Taking Their Toll. After Touring With The Dick Clark Caravan Of Stars The Cavaliers Quit On The Road Returning Back To San Angelo. A Short Time Later Sonley Roush (Road Mgr.) Died In A Car Crash While Touring With J. Frank, Murry Kellum (Long Tall Texan), Travis Wammack (Scratchy), Jerry Graham (Bass), Phil Trunzo (Drums) And Buddy Croyle (Guitar/Sax). The Song, Last Kiss, Had Been Based On An Actual Event That Took The Lives Of 3 Teens In Georgia. -

UP SONGS Most of Us Have Been Through Break-‐Ups Before. They'r

BEST BREAK-UP SONGS Most of us have been through break-ups before. They're devastating. These are my Top 20 saddest modern break-up songs. (When I say "modern," I mean that the song is recent. Not from pre-1995). My girlfriend broke up with me a week ago, and I'm still heartbroken. Yes, I'm lesbian. Thx i was woundering I just broke up with my boyfriend so I can't exactly keep listening to Thinking Out Loud and Adore You... If anyone has some break-up-song recommendations, I like most types of music. Please only suggest recent songs (2012 the oldest) and please nothing upbeat, it just wouldn't fit right. Sad Song- Nashville Cast Nothing- The Script Out of Goodbyes - Maroon 5 ft. Lady A. Superheroes - The Script Lonely Eyes - Chris Young Not Over You - Gavin DeGraw Who's Gonna Save Us - Gavin DeGraw Wanted You More - Lady A. Just from my playlist. :) The heart wants what it wants selena gomez ♡ Katy Perry - The One That Got Away Bruno Mars - When I was your man Pink - Just Give Me A Reason Tom Odell - Another Love My Chemical Romance - I Don't Love You Pearl Jam - Last Kiss Tegan and Sara - Nineteen Mary J. Blige - Sorry Seems To Be The Hardest Word Yuna - Random Awesome Just saying if any of you are having a bad day if you listen to Avril's songs you'll be able to find a lot of them relatable and her music always helps me. So y'all should go listen to her albums and see which songs will help you the most coz no lie, they really really help. -

"Catch the Wind"

DESCENDANTS IRISH THE OF BEST THE GOOD SO FAR SO fall the in nationally Touring Wind" The "Catch single/video the including songs, .19 Contains , " ". ! '"'. 08141 No. Registration Mail Publication GST) .20 plus ($2.80 $3.00 1999 6, September - 20 No. 69 Volume 3 paae See - GiElesValtquetie.., and re Mo Socan'slinda from plaques 01 iecehies -SARAHCLACHL1 a. 100 HIT TRACKS New Bowie release a David Bowie, one of music's most innc will take the recording industry anothe & where to find them in September, when his new album, h( available for download via the interne Record Distributor Codes: Canada's Only National 100 Hit Tracks Survey BMG - N EMI - F Universal - J Virgin Records America announce Polygram - Q Sony - H Warner - P indicates biggest mover in conjunction with fifty leading music album will be available on the 'net S TW LW WOSEPTEMBER 6, 1999 Bruce Barker name 1 1 13 IF YOU HAD MY LOVE 35 39 6 SMILE 68 67 40 BABY ONE MORE TIME Jennifer Lopez - On The 6 Vitamin C - Self Titled Britney Spears - Baby One More Time Work 69351 (pro single) - P Elektra 62406 (comp 405) - P Jive 41651 (pro single) -N Bruce "The Barkman" Barker has been 1M 7 13 GENIE IN A BOTTLE 36 25 21 SOMETIMES 69 64 26 ANYTHING BUT DOWN director of Toronto's CFRB. He succee Christina Aguilera - Self Titled Britney Spears - ... Baby One More Time Sheryl Crow - The Globe Sessions RCA (CD Track) - N Jive 41651 (CD Track) - N ARM 540959 (CD Track) - J Bill Stephenson, a sports broadcast let 3 2 14 ALL STAR 37 29 20 CLOUD #9 70 63 20 UNTIL YOU LOVED ME covered forty years of sports, most ofi Smash Mouth - Astro Lounge Bryan Adams - On A Day Like Today eA The Moffatts - Never Been Kissed O.S.T. -

CHICAGO, ILLINOIS SUNDAY, JULY 21, 1991 LOCATION CHICAGO, IL Cabaret Metro SET 1 1

CHICAGO, ILLINOIS SUNDAY, JULY 21, 1991 LOCATION CHICAGO, IL Cabaret Metro SET 1 1. Wash 2. Once 3. Even Flow 4. State Of Love And Trust 5. Alive 6. Why Go CHICAGO, ILLINOIS FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 29, 1991 LOCATION CHICAGO, IL Aragon Ballroom SET 1 1. Release 2. Even Flow 3. Smells Like Teen Spirit 4. Once 5. Alive 6. Jeremy 7. Why Go 8. Porch CHICAGO, ILLINOIS SATURDAY, MARCH 28, 1992 LOCATION CHICAGO, IL Cabaret Metro SET 1 1. Release 2. Even Flow 3. Improv (You Tell Me) 4. Rockin' In The Free World 5. Once 6. State Of Love And Trust 7. Alive 8. Black 9. Deep 10. Jeremy 11. Why Go 12. Porch TINLEY PARK, ILLINOIS SUNDAY, AUGUST 02, 1992 LOCATION TINLEY PARK, IL World Music Amphitheater SET 1 1. Summertime Rolls 2. Why Go 3. Deep 4. Jeremy 5. Even Flow 6. Alive 7. Black 8. Once 9. Porch CHICAGO, ILLINOIS THURSDAY, MARCH 10, 1994 LOCATION CHICAGO, IL Chicago Stadium SET 1 1. Release 2. Animal 3. Go 4. Even Flow 5. Dissident 6. Empire Carpet song 7. State Of Love And Trust 8. Why Go 9. Jeremy 10. Glorified G 11. Daughter 12. The Real Me 13. Not For You 14. Rearviewmirror 15. Blood 16. Alive 17. Porch 18. Garden 19. Happy Birthday (Jeff) 20. Spin The Black Circle 21. Black 22. Tremor Christ 23. Footsteps 24. Rockin' In The Free World 25. I Won't Back Down 26. Leash 27. Sonic Reducer Indifference CHICAGO, ILLINOIS SUNDAY, MARCH 13, 1994 LOCATION CHICAGO, IL New Regal Theater SET 1 1. -

Copyright © 2019 Kenneth William Lovett All Rights Reserved. The

Copyright © 2019 Kenneth William Lovett All rights reserved. The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary has permission to reproduce and disseminate this document in any form by any means for purposes chosen by the Seminary, including, without limitation, preservation or instruction. THE NEGATIVE MOTIF OF THE SEA IN THE OLD TESTAMENT __________________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary __________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________________ by Kenneth William Lovett May 2019 APPROVAL SHEET THE NEGATIVE MOTIF OF THE SEA IN THE OLD TESTAMENT Kenneth William Lovett Read and Approved by: __________________________________________ Terry J. Betts (Chair) __________________________________________ Duane A. Garrett __________________________________________ Russell T. Fuller Date ______________________________ For the glory of God. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE ..................................................................... vi Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION AND METHODOLOGY . 1 Thesis ................................................................ 2 Outline ............................................................... 4 Methodology . 5 2. HERMANN GUNKEL . 7 Significant Works . 9 Challenges ........................................................... 24 Conclusion . 28 3. HISTORY OF SCHOLARSHIP . 29 Significant Contributors .. 30 Conclusion . 48 4. THE NEGATIVE MOTIF OF THE SEA IN ANE LITERATURE ................................................ -

The Body by the Canal

The Body by the Canal By David Bowles September of 1987 wasn’t much different from September of 1986. My dad was still gone, we were still living on food stamps and welfare, I was still the lone freak at my high school, trapped in this conservative border town, unusual even for the circle of outcasts that had formed around me. Every girl I dated dumped me. The teachers thought I was too smug for my own good. I crossed out the days on my calendar, counting down toward graduation. Escape. Then the neighbors moved in downstairs, and everything changed. It was a Saturday. Luis, Javi, and I were across the street at the Pharr Civic Center, taking turns falling off a beat-up skateboard we’d scammed off a rich white kid from McAllen. “Is that a dude or a chick?” Luis asked. I looked over at the thin, elegant figure struggling to pull a box from the trunk of an old sedan. Longish hair teased wildly. Knee-high boots with one-inch heels. Bangles, bracelets, and a bright pink Swatch on the left wrist. A satiny black shirt with a frilly collar. Lips bright with color. Eyelids shaded. As out of place in this shitty neighborhood as a peacock among chickens. I knew the feeling. “I dunno,” I said. But my stomach did a pirouette as the newcomer turned to look at us. Boy or girl, the kid was beautiful. And from my own experience, this town would do all it could to destroy that beauty. “Only one way to find out,” Javi said, stamping on the back of the skateboard so it popped straight up. -

10 07 2020 Playlist

Friday Fest ~ 10 July 2020 Track Title Artist CD / Album 01 Yolnu Woman Yothu Yindi Homeland Movement 02 Exhilarating Sadness The Saw Doctors All The Way From Tuam 03 My Special Child Sinead O'Connor Celtic Heart 04 Botany Bay Claddagh Easy & Slow 05 Don't Leave Me This Way Catherine Traicos & the Starry Night Gloriosa 06 Piece of My Heart Janis Joplin Janis Joplin's Greatest Hits 07 Merman Tori Amos No Boundaries - A Benefit for the Kosovar Refugees 08 The Time British India Homebake 2005 09 My Time Mark Wilkinson Cellophane Life 10 A World of Our Own The Seekers The Seekers Again 11 Gordon Basic Shape Boat Without a Sail 12 Corn Circles The Waterboys Dream Harder 13 The Sweetest Name Gurrumul The Gospel Album 14 Last Kiss Pearl Jam No Boundaries - A Benefit for the Kosovar Refugees 15 I'm Gonna Be (500 Miles) The Proclaimers The Best Scottish Album in the World.....Ever 16 Morning Has Broken Cat Stevens The Very Best Of Cat Stevens 17 The Consort Rufus Wainwright Poses 18 Hallelujah Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds No More Shall We Part 19 Knock'on Heaven's Door Dunblane The Best Scottish Album in the World.....Ever 20 Ain't Nothing You Can Do Andrew Strong The Best Of The Commitments 21 Orphans of the Empire Johnny Clegg (Savuka) Anthology 22 Riverman Pigram Brothers Jiir 23 Oceans Ernest Ellis & The Panamas Kings Canyon 24 Mull of Kintyre Paul McCartney & Wings The Best Scottish Album in the World.....Ever 25 Every Beat of My Heart Rod Stewart The Best Scottish Album in the World.....Ever 26 The Day the World Stood Still Edmund Choi, Melbourne Symphony Orchestra Music From The Motion Pichure The Dish. -

Egypt's Hieroglyphs Contain a Cultural Memory of Creation and Noah's Flood

The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism Volume 7 Article 36 2013 Egypt's Hieroglyphs Contain a Cultural Memory of Creation and Noah's Flood Gavin M. Cox Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Browse the contents of this volume of The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism. Recommended Citation Cox, Gavin M. (2013) "Egypt's Hieroglyphs Contain a Cultural Memory of Creation and Noah's Flood," The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism: Vol. 7 , Article 36. Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings/vol7/iss1/36 Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Creationism. Pittsburgh, PA: Creation Science Fellowship EGYPT'S HIEROGLYPHS CONTAIN CULTURAL MEMORIES OF CREATION AND NOAH'S FLOOD Gavin M. Cox, BA Hons (Theology, LBC). 26 The Firs Park, Bakers Hill, Exeter, Devon, UK, EX2 9TD. KEYWORDS: Flood, onomatology, eponym, Hermopolitan Ogdoad, Edfu, Heliopolis, Memphis, Hermopolis, Ennead, determinative, ideograph, hieroglyphic, Documentary Hypothesis (DH). ABSTRACT A survey of standard Egyptian Encyclopedias and earliest mythology demonstrates Egyptian knowledge of Creation and the Flood consistent with the Genesis account. -

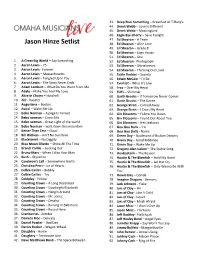

Current Setlist

43. Deep Blue Something – Breakfast At Tiffany’s 44. Derek Webb – Love Is Different 45. Derek Webb – Mockingbird 46. Eagle Eye Cherry – Save Tonight 47. Ed Sheeran – A Team Jason Hinze Setlist 48. Ed Sheeran – Afire Love 49. Ed Sheeran – Grade 8 50. Ed Sheeran – Lego House 51. Ed Sheeran – One 1. A Great Big World – Say Something 52. Ed Sheeran - Photograph 2. Aaron Lewis – 75 53. Ed Sheeran – Shirtslieeves 3. Aaron Lewis - Forever 54. Ed Sheeran – Thinking Out Loud 4. Aaron Lewis – Massachusetts 55. Eddie Vedder – Society 5. Aaron Lewis – Tangled Up In You 56. Edwin McCain – I’ll Be 6. Aaron Lewis – The Story Never Ends 57. Everlast – What It’s Like 7. Adam Lambert – What Do You Want From Me 58. Fray – Over My Head 8. Adele – Make You Feel My Love 59. FUEL – Shimmer 9. Alice In Chains – Nutshell 60. Garth Brooks – If Tomorrow Never Comes 10. AIC - Rooster 61. Garth Brooks – The Dance 11. Augustana – Boston 62. George Strait – Carried Away 12. Avicci – Wake Me Up 63. George Strait – I Cross My Heart 13. Bebo Norman – A page Is Turned 64. Gin Blossoms – Follow You Down 14. Bebo norman – Cover Me 65. Gin Blossoms – Found Out About You 15. Bebo norman – Great Light of the world 66. Gin Blossoms – Hey Jealousy 16. Bebo Norman – walk down this mountain 67. Goo Goo Dolls – Iris 17. Better Than Ezra – Good 68. Goo Goo Dolls - Name 18. Bill Withers – Ain’t No Sunshine 69. Green Day – Boulevard of Broken Dreams 19. Blackstreet – No Diggity 70. Green Day – Good Riddance 20. -

Canaanite/Ugaritic Mythology

Canaanite/Ugaritic Mythology I. Who do we mean by 'Canaanites'? Linguistically, the ancient Semites have been broadly classified into Eastern and Western groups. The Eastern group is represented most prominently by Akkadian, the language of the Assyrians and Babylonians, who inhabited the Tigris and Euphrates river valleys. The Western group is further broken down into the Southern and Northern groups. The South Western Semites inhabited Arabia and Ethiopia while the North Western Semites occupied the Levant - the regions that used to be Palestine as well as what is now Syria, Israel and Lebanon, the regions often referred to in the Bible as Canaan. Recent archaeological finds indicate that the inhabitants of the region themselves referred to the land as 'ca-na-na-um' as early as the mid-third millennium B.C.E. (Aubet p. 9) Variations on that name in reference to the country and its inhabitants continue through the first millennium B.C.E. The word appears to have two etymologies. On one end, represented by the Hebrew cana'ani the word meant merchant, an occupation for which the Canaanites were well known. On the other end, as represented by the Akkadian kinahhu, the word referred to the red-colored wool which was a key export of the region. When the Greeks encountered the Canaanites, it may have been this aspect of the term which they latched onto as they renamed the Canaanites the Phoenikes or Phoenicians, which may derive from a word meaning red or purple, and descriptive of the cloth for which the Greeks too traded.