The Body by the Canal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pearl Jam Sacramento, California October 30, 2000 Mp3, Flac, Wma

Pearl Jam Sacramento, California October 30, 2000 mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Sacramento, California October 30, 2000 Country: US Released: 2001 Style: Alternative Rock, Grunge, Classic Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1978 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1593 mb WMA version RAR size: 1985 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 333 Other Formats: MP3 AUD DTS DMF MP2 AU APE Tracklist 1-1 Whipping 1-2 Insignificance 1-3 Animal 1-4 Last Exit 1-5 State Of Love And Trust 1-6 Given To Fly 1-7 Small Town 1-8 Tremor Christ 1-9 Even Flow 1-10 Daughter 1-11 Betterman 1-12 Jeremy 1-13 Light Years 1-14 Immortality 1-15 Do The Evolution 1-16 Brain Of J 2-1 RVM 2-2 Encore Break 2-3 Breakerfall 2-4 Corduroy 2-5 Last Kiss 2-6 The Kids Are Alright 2-7 Go 2-8 Yellow Ledbetter Companies, etc. Mastered At – RFI Mastering Credits Design Concept – J.A.* Design, Layout – Brad Klausen Engineer – John Burton Mixed By – Brett Eliason Notes No. 67 (of 72) of the 2000 Binaural Tour Official Bootleg series. Comes in a Cardboard Gatefold Sleeve. The barcode, label name and catalog# are not visible anywhere on the cover sleeve or discs. They were indicated only on the original sealing sticker. Manufactured in Carrollton, GA (USA). Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode (Scanned): 696998562622 Related Music albums to Sacramento, California October 30, 2000 by Pearl Jam Pearl Jam - October 09 2009, San Diego, CA Pearl Jam - Новая Фонотека В Кармане Pearl Jam - 19 6 00 - Hala Tivoli - Ljubljana, Slovenia Pearl Jam - New York, NY - July 8th 2003 Pearl Jam - Soldier Field Chicago, IL 7/11/95 Pearl Jam - Jones Beach, New York - August 24, 2000 Pearl Jam - St. -

AND HE BUILT a CROOKED HOUSE Robert Heinlein

NELSON FEB 1941 p®llKfP WM — Look out for a COLD . .watch your THROAT gargle ListerineQuick! A careless sneeze, or an explosive cough, can shoot after a Listerine gargle. Even one hour after, reduc- troublesome germs in your direction at mile-a- tions up to 80% in the number of surface germs minute speed. In case they invade the tissues of associated with colds and sore throat were noted. your throat, you may be in for throat irritation, a That is why, we believe, Listerine in the last nine cold—or worse. years has built up such an impressive test record If you have been thus exposed, better gargle against colds . why thousands of people gargle witli it at first hint a sore throat. with Listerine Antiseptic at your earliest oppor- the of cold or simple tunity . Listerine kills millions of thegerms on mouth Fewer and Milder Colds in Tests and throat surfaces known as "secondary invaders” These tests showed that those who gargled with . often helps render them powerless to invade Listerine twice a day had fewer colds, milder colds, the tissue and aggravate infection. Used early and and colds of shorter duration than those who did often, Listerine may head off a cold, or reduce the not gargle. And fewer sore throats, also. severity of one already started. So remember, if you have been exposed to others Amazing Germ Reductions in Tests suffering from colds, if you feel a cold coming on, Tests have shown germ reductions ranging to gargle Listerine quick.! on mouth and throat surfaces fifteen minutes Lambert Pharmacal Co., St. -

J. Frank Wilson

J. FRANK WILSON J. Frank was born December 11, 1941 in Lufkin, TX. In 1962 J. Frank Wilson, After Being Discharged From Goodfellow Air Force Base, Auditioned For The San Angelo Based Group "The Cavaliers" (Sid Holmes-Lewis Elliott-Bob Zeller-Ray Smith). J. Frank Would Then Be Discovered By Independent Record Producer Sonley Roush Who Had Booked The Band At The Blue Note Club (3rd and Birdwell St) In Big Spring, Texas In 1962. After Signing A 3 Year Manager's Contract With Sid Holmes, In 1963, Frank Took A Leave Of Absents. In 1964 J. Frank Was Re-Instated As The Lead Singer For The Cavaliers Replacing John Maberry. The Cavaliers, J. Frank Wilson, Buddy Croyle, Lewis Elliott, Roland Atkinson, Jim Wynne And A Girl Who Sang In Church (unknown) Went About The Business Of Copying Wayne Cochran's Record In Ron Newdoll's Studio In San Angelo. With J. Frank In Top Form The Record (First Released On Tamara 761 & Le Cam 722) On Josie Started Moving Up The Billboard Charts. It Wasn't Long After This That Contract Disputes, Law Suits, And Greedy Un- Scrupulous Promoters Began Taking Their Toll. After Touring With The Dick Clark Caravan Of Stars The Cavaliers Quit On The Road Returning Back To San Angelo. A Short Time Later Sonley Roush (Road Mgr.) Died In A Car Crash While Touring With J. Frank, Murry Kellum (Long Tall Texan), Travis Wammack (Scratchy), Jerry Graham (Bass), Phil Trunzo (Drums) And Buddy Croyle (Guitar/Sax). The Song, Last Kiss, Had Been Based On An Actual Event That Took The Lives Of 3 Teens In Georgia. -

UP SONGS Most of Us Have Been Through Break-‐Ups Before. They'r

BEST BREAK-UP SONGS Most of us have been through break-ups before. They're devastating. These are my Top 20 saddest modern break-up songs. (When I say "modern," I mean that the song is recent. Not from pre-1995). My girlfriend broke up with me a week ago, and I'm still heartbroken. Yes, I'm lesbian. Thx i was woundering I just broke up with my boyfriend so I can't exactly keep listening to Thinking Out Loud and Adore You... If anyone has some break-up-song recommendations, I like most types of music. Please only suggest recent songs (2012 the oldest) and please nothing upbeat, it just wouldn't fit right. Sad Song- Nashville Cast Nothing- The Script Out of Goodbyes - Maroon 5 ft. Lady A. Superheroes - The Script Lonely Eyes - Chris Young Not Over You - Gavin DeGraw Who's Gonna Save Us - Gavin DeGraw Wanted You More - Lady A. Just from my playlist. :) The heart wants what it wants selena gomez ♡ Katy Perry - The One That Got Away Bruno Mars - When I was your man Pink - Just Give Me A Reason Tom Odell - Another Love My Chemical Romance - I Don't Love You Pearl Jam - Last Kiss Tegan and Sara - Nineteen Mary J. Blige - Sorry Seems To Be The Hardest Word Yuna - Random Awesome Just saying if any of you are having a bad day if you listen to Avril's songs you'll be able to find a lot of them relatable and her music always helps me. So y'all should go listen to her albums and see which songs will help you the most coz no lie, they really really help. -

"Catch the Wind"

DESCENDANTS IRISH THE OF BEST THE GOOD SO FAR SO fall the in nationally Touring Wind" The "Catch single/video the including songs, .19 Contains , " ". ! '"'. 08141 No. Registration Mail Publication GST) .20 plus ($2.80 $3.00 1999 6, September - 20 No. 69 Volume 3 paae See - GiElesValtquetie.., and re Mo Socan'slinda from plaques 01 iecehies -SARAHCLACHL1 a. 100 HIT TRACKS New Bowie release a David Bowie, one of music's most innc will take the recording industry anothe & where to find them in September, when his new album, h( available for download via the interne Record Distributor Codes: Canada's Only National 100 Hit Tracks Survey BMG - N EMI - F Universal - J Virgin Records America announce Polygram - Q Sony - H Warner - P indicates biggest mover in conjunction with fifty leading music album will be available on the 'net S TW LW WOSEPTEMBER 6, 1999 Bruce Barker name 1 1 13 IF YOU HAD MY LOVE 35 39 6 SMILE 68 67 40 BABY ONE MORE TIME Jennifer Lopez - On The 6 Vitamin C - Self Titled Britney Spears - Baby One More Time Work 69351 (pro single) - P Elektra 62406 (comp 405) - P Jive 41651 (pro single) -N Bruce "The Barkman" Barker has been 1M 7 13 GENIE IN A BOTTLE 36 25 21 SOMETIMES 69 64 26 ANYTHING BUT DOWN director of Toronto's CFRB. He succee Christina Aguilera - Self Titled Britney Spears - ... Baby One More Time Sheryl Crow - The Globe Sessions RCA (CD Track) - N Jive 41651 (CD Track) - N ARM 540959 (CD Track) - J Bill Stephenson, a sports broadcast let 3 2 14 ALL STAR 37 29 20 CLOUD #9 70 63 20 UNTIL YOU LOVED ME covered forty years of sports, most ofi Smash Mouth - Astro Lounge Bryan Adams - On A Day Like Today eA The Moffatts - Never Been Kissed O.S.T. -

CHICAGO, ILLINOIS SUNDAY, JULY 21, 1991 LOCATION CHICAGO, IL Cabaret Metro SET 1 1

CHICAGO, ILLINOIS SUNDAY, JULY 21, 1991 LOCATION CHICAGO, IL Cabaret Metro SET 1 1. Wash 2. Once 3. Even Flow 4. State Of Love And Trust 5. Alive 6. Why Go CHICAGO, ILLINOIS FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 29, 1991 LOCATION CHICAGO, IL Aragon Ballroom SET 1 1. Release 2. Even Flow 3. Smells Like Teen Spirit 4. Once 5. Alive 6. Jeremy 7. Why Go 8. Porch CHICAGO, ILLINOIS SATURDAY, MARCH 28, 1992 LOCATION CHICAGO, IL Cabaret Metro SET 1 1. Release 2. Even Flow 3. Improv (You Tell Me) 4. Rockin' In The Free World 5. Once 6. State Of Love And Trust 7. Alive 8. Black 9. Deep 10. Jeremy 11. Why Go 12. Porch TINLEY PARK, ILLINOIS SUNDAY, AUGUST 02, 1992 LOCATION TINLEY PARK, IL World Music Amphitheater SET 1 1. Summertime Rolls 2. Why Go 3. Deep 4. Jeremy 5. Even Flow 6. Alive 7. Black 8. Once 9. Porch CHICAGO, ILLINOIS THURSDAY, MARCH 10, 1994 LOCATION CHICAGO, IL Chicago Stadium SET 1 1. Release 2. Animal 3. Go 4. Even Flow 5. Dissident 6. Empire Carpet song 7. State Of Love And Trust 8. Why Go 9. Jeremy 10. Glorified G 11. Daughter 12. The Real Me 13. Not For You 14. Rearviewmirror 15. Blood 16. Alive 17. Porch 18. Garden 19. Happy Birthday (Jeff) 20. Spin The Black Circle 21. Black 22. Tremor Christ 23. Footsteps 24. Rockin' In The Free World 25. I Won't Back Down 26. Leash 27. Sonic Reducer Indifference CHICAGO, ILLINOIS SUNDAY, MARCH 13, 1994 LOCATION CHICAGO, IL New Regal Theater SET 1 1. -

10 07 2020 Playlist

Friday Fest ~ 10 July 2020 Track Title Artist CD / Album 01 Yolnu Woman Yothu Yindi Homeland Movement 02 Exhilarating Sadness The Saw Doctors All The Way From Tuam 03 My Special Child Sinead O'Connor Celtic Heart 04 Botany Bay Claddagh Easy & Slow 05 Don't Leave Me This Way Catherine Traicos & the Starry Night Gloriosa 06 Piece of My Heart Janis Joplin Janis Joplin's Greatest Hits 07 Merman Tori Amos No Boundaries - A Benefit for the Kosovar Refugees 08 The Time British India Homebake 2005 09 My Time Mark Wilkinson Cellophane Life 10 A World of Our Own The Seekers The Seekers Again 11 Gordon Basic Shape Boat Without a Sail 12 Corn Circles The Waterboys Dream Harder 13 The Sweetest Name Gurrumul The Gospel Album 14 Last Kiss Pearl Jam No Boundaries - A Benefit for the Kosovar Refugees 15 I'm Gonna Be (500 Miles) The Proclaimers The Best Scottish Album in the World.....Ever 16 Morning Has Broken Cat Stevens The Very Best Of Cat Stevens 17 The Consort Rufus Wainwright Poses 18 Hallelujah Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds No More Shall We Part 19 Knock'on Heaven's Door Dunblane The Best Scottish Album in the World.....Ever 20 Ain't Nothing You Can Do Andrew Strong The Best Of The Commitments 21 Orphans of the Empire Johnny Clegg (Savuka) Anthology 22 Riverman Pigram Brothers Jiir 23 Oceans Ernest Ellis & The Panamas Kings Canyon 24 Mull of Kintyre Paul McCartney & Wings The Best Scottish Album in the World.....Ever 25 Every Beat of My Heart Rod Stewart The Best Scottish Album in the World.....Ever 26 The Day the World Stood Still Edmund Choi, Melbourne Symphony Orchestra Music From The Motion Pichure The Dish. -

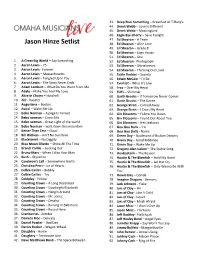

Current Setlist

43. Deep Blue Something – Breakfast At Tiffany’s 44. Derek Webb – Love Is Different 45. Derek Webb – Mockingbird 46. Eagle Eye Cherry – Save Tonight 47. Ed Sheeran – A Team Jason Hinze Setlist 48. Ed Sheeran – Afire Love 49. Ed Sheeran – Grade 8 50. Ed Sheeran – Lego House 51. Ed Sheeran – One 1. A Great Big World – Say Something 52. Ed Sheeran - Photograph 2. Aaron Lewis – 75 53. Ed Sheeran – Shirtslieeves 3. Aaron Lewis - Forever 54. Ed Sheeran – Thinking Out Loud 4. Aaron Lewis – Massachusetts 55. Eddie Vedder – Society 5. Aaron Lewis – Tangled Up In You 56. Edwin McCain – I’ll Be 6. Aaron Lewis – The Story Never Ends 57. Everlast – What It’s Like 7. Adam Lambert – What Do You Want From Me 58. Fray – Over My Head 8. Adele – Make You Feel My Love 59. FUEL – Shimmer 9. Alice In Chains – Nutshell 60. Garth Brooks – If Tomorrow Never Comes 10. AIC - Rooster 61. Garth Brooks – The Dance 11. Augustana – Boston 62. George Strait – Carried Away 12. Avicci – Wake Me Up 63. George Strait – I Cross My Heart 13. Bebo Norman – A page Is Turned 64. Gin Blossoms – Follow You Down 14. Bebo norman – Cover Me 65. Gin Blossoms – Found Out About You 15. Bebo norman – Great Light of the world 66. Gin Blossoms – Hey Jealousy 16. Bebo Norman – walk down this mountain 67. Goo Goo Dolls – Iris 17. Better Than Ezra – Good 68. Goo Goo Dolls - Name 18. Bill Withers – Ain’t No Sunshine 69. Green Day – Boulevard of Broken Dreams 19. Blackstreet – No Diggity 70. Green Day – Good Riddance 20. -

Total Tracks Number: 1108 Total Tracks Length: 76:17:23 Total Tracks Size: 6.7 GB

Total tracks number: 1108 Total tracks length: 76:17:23 Total tracks size: 6.7 GB # Artist Title Length 01 00:00 02 2 Skinnee J's Riot Nrrrd 03:57 03 311 All Mixed Up 03:00 04 311 Amber 03:28 05 311 Beautiful Disaster 04:01 06 311 Come Original 03:42 07 311 Do You Right 04:17 08 311 Don't Stay Home 02:43 09 311 Down 02:52 10 311 Flowing 03:13 11 311 Transistor 03:02 12 311 You Wouldnt Believe 03:40 13 A New Found Glory Hit Or Miss 03:24 14 A Perfect Circle 3 Libras 03:35 15 A Perfect Circle Judith 04:03 16 A Perfect Circle The Hollow 02:55 17 AC/DC Back In Black 04:15 18 AC/DC What Do You Do for Money Honey 03:35 19 Acdc Back In Black 04:14 20 Acdc Highway To Hell 03:27 21 Acdc You Shook Me All Night Long 03:31 22 Adema Giving In 04:34 23 Adema The Way You Like It 03:39 24 Aerosmith Cryin' 05:08 25 Aerosmith Sweet Emotion 05:08 26 Aerosmith Walk This Way 03:39 27 Afi Days Of The Phoenix 03:27 28 Afroman Because I Got High 05:10 29 Alanis Morissette Ironic 03:49 30 Alanis Morissette You Learn 03:55 31 Alanis Morissette You Oughta Know 04:09 32 Alaniss Morrisete Hand In My Pocket 03:41 33 Alice Cooper School's Out 03:30 34 Alice In Chains Again 04:04 35 Alice In Chains Angry Chair 04:47 36 Alice In Chains Don't Follow 04:21 37 Alice In Chains Down In A Hole 05:37 38 Alice In Chains Got Me Wrong 04:11 39 Alice In Chains Grind 04:44 40 Alice In Chains Heaven Beside You 05:27 41 Alice In Chains I Stay Away 04:14 42 Alice In Chains Man In The Box 04:46 43 Alice In Chains No Excuses 04:15 44 Alice In Chains Nutshell 04:19 45 Alice In Chains Over Now 07:03 46 Alice In Chains Rooster 06:15 47 Alice In Chains Sea Of Sorrow 05:49 48 Alice In Chains Them Bones 02:29 49 Alice in Chains Would? 03:28 50 Alice In Chains Would 03:26 51 Alien Ant Farm Movies 03:15 52 Alien Ant Farm Smooth Criminal 03:41 53 American Hifi Flavor Of The Week 03:12 54 Andrew W.K. -

The Arts Issue March 15, 2001 Darla's Women's Day Rally Didn't Quite Get the Participation She Was Looking For

TTHEHE PPRIMARYRIMARY SSOURCEOURCE VV EE RR II TT AA SS SS II NN EE DD OO LL OO Tufts' Voice of Reason The Arts Issue March 15, 2001 Darla's Women's Day rally didn't quite get the participation she was looking for. Losing enthusiasm for politics as usual? Join the SOURCE! We're always on the lookout for new writers, editors, illustrators, and production staff. Call Josh at x1602 or email [email protected] 2 THE PRIMARY SOURCE, MARCH 15, 2001 THE PRIMARY SOURCE Vol. XIX • The Journal of Conservative Thought at Tufts University • No. 10 D E P A R T M E N T S From the Editor 4 Want your band to lose credibility? Move it to the Left. Commentary 6 More shady Clinton dealings and a communique from the dead Fortnight in Review 8 An evil frog and anecdotes from the SOURCE shooting trip Notable and Quotable 24 A R T I C L E S Nationally Endowed 10 by Ezra Klughaupt page 8 When the government funds the arts, strippers become "performance artists." A Million Manga 15 by Chris Kohler Think you know all there is to know about Japanese comics? All About Oscar 16 by Michael Santorelli This year, will the Academy abandon the political courage? A Modest Proposal 18 by Stephen Tempesta The Brooklyn Museum hosts more religion-bashing art. Days of Future Passed 19 by Lew Titterton Progressive Rock or regressive crap? Let the listener decide. Online Larceny 20 by Andrew Gibbs page 21 Napster's days are numbered—good riddance! Love Story 22 by Alyssa Heumann Filmmaker Wong Kar-Wai presents a meticulously crafted vision of romance. -

Popular Wedding Covers (346)

The Atlanta Wedding Band is proud to have performed over 100 weddings since the beginning of 2011. We have the distinct honor of being a 5 star band on www.gigmasters.com, not only that, but every client that has booked us through that site has given us 5 out of 5! Atlanta Wedding Band 1418 Dresden Drive Unit 365, Atlanta, Georgia, 30319, United States. 404-272-0337 Popular Wedding Covers (346) For an all inclusive list (700+), scroll further down! Motown/R&B/Funk/Dance (53) Al Green Let’s Stay Together Aretha Franklin Ain’t No Mountain High Enough BeeGees Stayin Alive Ben E. King Stand by Me Beyonce Knowles Irreplaceable Bill Withers Ain’t No Sunshine Lean On Me Black Eyed Peas I Got a Feeling Bruno Mars (Mark Ronson) Marry You Uptown Funk Cee-Lo Green Forget You Chubby Checker The Twist The Commodores Brick House The Contours Do You Love Me Cupid Cupid Shuffle Dexy’s Midnight Runners Come on Eileen Earth Wind and Fire September The Foundations Build me Up Buttercup The Four Tops I Can’t Help Myself (Sugar pie, Honey Bunch) Hall and Oates You Make My Dreams The Isley Brothers Shout Jackson 5 ABC I Want You Back James Brown I Feel Good Jason Derulo It Girl Want to Want Me Kenny Loggins Footloose King Harvest Dancing in the Moonlight Kool and the Gang Celebration Lionel Ritchie All Night Long Louis Armstrong What a Wonderful World Marvin Gaye How Sweet It Is Let’s Get it On Sexual Healing Michael Jackson Billie Jean Man in the Mirror Otis Redding Sittin on the Dock of the Bay Outkast Hey Ya Sorry Ms. -

Inventory to Archival Boxes in the Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress

INVENTORY TO ARCHIVAL BOXES IN THE MOTION PICTURE, BROADCASTING, AND RECORDED SOUND DIVISION OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Compiled by MBRS Staff (Last Update December 2017) Introduction The following is an inventory of film and television related paper and manuscript materials held by the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress. Our collection of paper materials includes continuities, scripts, tie-in-books, scrapbooks, press releases, newsreel summaries, publicity notebooks, press books, lobby cards, theater programs, production notes, and much more. These items have been acquired through copyright deposit, purchased, or gifted to the division. How to Use this Inventory The inventory is organized by box number with each letter representing a specific box type. The majority of the boxes listed include content information. Please note that over the years, the content of the boxes has been described in different ways and are not consistent. The “card” column used to refer to a set of card catalogs that documented our holdings of particular paper materials: press book, posters, continuity, reviews, and other. The majority of this information has been entered into our Merged Audiovisual Information System (MAVIS) database. Boxes indicating “MAVIS” in the last column have catalog records within the new database. To locate material, use the CTRL-F function to search the document by keyword, title, or format. Paper and manuscript materials are also listed in the MAVIS database. This database is only accessible on-site in the Moving Image Research Center. If you are unable to locate a specific item in this inventory, please contact the reading room.