Religion and State HRP Religion and State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

M E O R O T a Forum of Modern Orthodox Discourse (Formerly Edah Journal)

M e o r o t A Forum of Modern Orthodox Discourse (formerly Edah Journal) Tishrei 5770 Special Edition on Modern Orthodox Education CONTENTS Editor’s Introduction to Special Tishrei 5770 Edition Nathaniel Helfgot SYMPOSIUM On Modern Orthodox Day School Education Scot A. Berman, Todd Berman, Shlomo (Myles) Brody, Yitzchak Etshalom,Yoel Finkelman, David Flatto Zvi Grumet, Naftali Harcsztark, Rivka Kahan, Miriam Reisler, Jeremy Savitsky ARTICLES What Should a Yeshiva High School Graduate Know, Value and Be Able to Do? Moshe Sokolow Responses by Jack Bieler, Yaakov Blau, Erica Brown, Aaron Frank, Mark Gottlieb The Economics of Jewish Education The Tuition Hole: How We Dug It and How to Begin Digging Out of It Allen Friedman The Economic Crisis and Jewish Education Saul Zucker Striving for Cognitive Excellence Jack Nahmod To Teach Tsni’ut with Tsni’ut Meorot 7:2 Tishrei 5770 Tamar Biala A Publication of Yeshivat Chovevei Torah REVIEW ESSAY Rabbinical School © 2009 Life Values and Intimacy Education: Health Education for the Jewish School, Yocheved Debow and Anna Woloski-Wruble, eds. Jeffrey Kobrin STATEMENT OF PURPOSE Meorot: A Forum of Modern Orthodox Discourse (formerly The Edah Journal) Statement of Purpose Meorot is a forum for discussion of Orthodox Judaism’s engagement with modernity, published by Yeshivat Chovevei Torah Rabbinical School. It is the conviction of Meorot that this discourse is vital to nurturing the spiritual and religious experiences of Modern Orthodox Jews. Committed to the norms of halakhah and Torah, Meorot is dedicated -

Torrón & W. Cole Durham, Jr. (Eds.), Religion and the Secular State

Javier Martínez-Torrón & W. Cole Durham, Jr. (eds.), Religion and the Secular State: National Reports, Servicio de PuBlicaciones de la Facultad de Derecho de la Universidad Complutense (Madrid, Spain), 2015, 898 pages. The book can be ordered directly via e-mail: [email protected]. Price: 40 euro + shipping costs. Discounted price for suBscriBers to ICLRS Newsletter: 35 euro (+ shipping) (indicate the promotional code “ICLRS” in your e-mail order) Recent years have seen religion assume an increasingly visible place in public life, with mixed results that have been aptly described in terms of the “ambivalence of the sacred”. Every state adopts some posture toward the religious life existing among its citizens. That posture is typically contested, leading to constant adjustments at the level of constitutional and statutory law, as well as constantly evolving judicial and administrative decisions. While some states continue to maintain a particular religious (i.e., non-secular) orientation, most have adopted some type of secular system. Among secular states, there are a range of possible positions with respect to secularity, ranging from regimes with a very high commitment to secularism to more accommodationist regimes to regimes that remain committed to neutrality of the state but allow high levels of cooperation with religions. The attitude toward secularity has significant implications for implementation of international and constitutional norms protecting freedom of religion or belief, and more generally for the co-existence of different communities of religion and belief within society. Not surprisingly, comparative examination of the secularity of contemporary states yields significant insights into the nature of pluralism, the role of religion in modern society, the relationship between religion and democracy, and more generally, into fundamental questions about the relationship of religion and the state. -

The Rebbe and the Yak

Hillel Halkin on King James: The Harold Bloom Version JEWISH REVIEW Volume 2, Number 3 Fall 2011 $6.95 OF BOOKS Alan Mintz The Rebbe and the Yak Ruth R. Wisse Yehudah Mirsky Adam Kirsch Moshe Halbertal The Faith of Reds On Law & Forgiveness Yehuda Amital Elli Fischer & Shai Secunda Footnote: the Movie! Ruth Gavison The Nation of Israel? Philip Getz Birthright & Diaspora PLUS Did Billie Holiday Sing Yo's Blues? Sermons & Anti-Sermons & MORE Editor Abraham Socher Publisher Eric Cohen The history of America — Senior Contributing Editor one fear, one monster, Allan Arkush Editorial Board at a time Robert Alter Shlomo Avineri “An unexpected guilty pleasure! Poole invites us Leora Batnitzky into an important and enlightening, if disturbing, Ruth Gavison conversation about the very real monsters that Moshe Halbertal inhabit the dark spaces of America’s past.” Hillel Halkin – J. Gordon Melton, Institute for the Study of American Religion Jon D. Levenson Anita Shapira “A well informed, thoughtful, and indeed frightening Michael Walzer angle of vision to a compelling American desire to J. H.H. Weiler be entertained by the grotesque and the horrific.” Leon Wieseltier – Gary Laderman, Emory University Ruth R. Wisse Available in October at fine booksellers everywhere. Steven J. Zipperstein Assistant Editor Philip Getz Art Director Betsy Klarfeld Business Manager baylor university press Lori Dorr baylorpress.com Interns Kif Leswing Arielle Orenstein The Jewish Review of Books (Print ISSN 2153-1978, An eloquent intellectual Online ISSN 2153-1994) is a quarterly publication of ideas and criticism published in Spring, history of the human Summer, Fall, and Winter, by Bee.Ideas, LLC., 745 Fifth Avenue, Suite 1400, New York, NY 10151. -

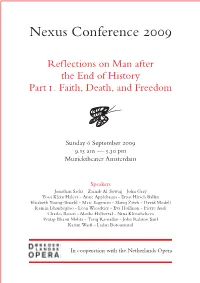

Nexus Conference 2009

Nexus Conference 2009 Reflections on Man after the End of History Part i . Faith, Death, and Freedom Sunday 6 September 2009 9.15 am — 5.30 pm Muziektheater Amsterdam Speakers Jonathan Sacks - Zainab Al-Suwaij - John Gray Yossi Klein Halevi - Anne Applebaum - Ernst Hirsch Ballin Elisabeth Young-Bruehl - Marc Sageman - Slavoj Žižek - David Modell Ramin Jahanbegloo - Leon Wieseltier - Eva Hoffman - Pierre Audi Charles Rosen - Moshe Halbertal - Nina Khrushcheva Pratap Bhanu Mehta - Tariq Ramadan - John Ralston Saul Karim Wasfi - Ladan Boroumand In cooperation with the Netherlands Opera Attendance at Nexus Conference 2009 We would be happy to welcome you as a member of the audience, but advance reservation of an admission ticket is compulsory. Please register online at our website, www.nexus-instituut.nl, or contact Ms. Ilja Hijink at [email protected]. The conference admission fee is € 75. A reduced rate of € 50 is available for subscribers to the periodical Nexus, who may bring up to three guests for the same reduced rate of € 50. A special youth rate of € 25 will be charged to those under the age of 26, provided they enclose a copy of their identity document with their registration form. The conference fee includes lunch and refreshments during the reception and breaks. Only written cancellations will be accepted. Cancellations received before 21 August 2009 will be free of charge; after that date the full fee will be charged. If you decide to register after 1 September, we would advise you to contact us by telephone to check for availability. The Nexus Conference will be held at the Muziektheater Amsterdam, Amstel 3, Amsterdam (parking and subway station Waterlooplein; please check details on www.muziektheater.nl). -

1 Beginning the Conversation

NOTES 1 Beginning the Conversation 1. Jacob Katz, Exclusiveness and Tolerance: Jewish-Gentile Relations in Medieval and Modern Times (New York: Schocken, 1969). 2. John Micklethwait, “In God’s Name: A Special Report on Religion and Public Life,” The Economist, London November 3–9, 2007. 3. Mark Lila, “Earthly Powers,” NYT, April 2, 2006. 4. When we mention the clash of civilizations, we think of either the Spengler battle, or a more benign interplay between cultures in individual lives. For the Spengler battle, see Samuel P. Huntington, The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996). For a more benign interplay in individual lives, see Thomas L. Friedman, The Lexus and the Olive Tree (New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1999). 5. Micklethwait, “In God’s Name.” 6. Robert Wuthnow, America and the Challenges of Religious Diversity (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005). “Interview with Robert Wuthnow” Religion and Ethics Newsweekly April 26, 2002. Episode no. 534 http://www.pbs.org/wnet/religionandethics/week534/ rwuthnow.html 7. Wuthnow, America and the Challenges of Religious Diversity, 291. 8. Eric Sharpe, “Dialogue,” in Mircea Eliade and Charles J. Adams, The Encyclopedia of Religion, first edition, volume 4 (New York: Macmillan, 1987), 345–8. 9. Archbishop Michael L. Fitzgerald and John Borelli, Interfaith Dialogue: A Catholic View (London: SPCK, 2006). 10. Lily Edelman, Face to Face: A Primer in Dialogue (Washington, DC: B’nai B’rith, Adult Jewish Education, 1967). 11. Ben Zion Bokser, Judaism and the Christian Predicament (New York: Knopf, 1967), 5, 11. 12. Ibid., 375. -

Reading Oz with Kashua

MINORIT ARIAN INTERVENTIONS AND NATIONAL IDENTITY: READING OZ WITH KASHUA Ari Ofengenden Brandeis University The "other" is never outside or beyond us; it emerges forcefully, within cultural discourse, when we think we speak most intimately and indigenously "between ourselves" (Homi Bhabha) This article attempts to read Amos Oz's celebrated autobiography, A Tale of Love and Darkness , with Sayed Kashua's autobiographical texts Dancing Arabs and Let it be Morning , as well as his television sitcom Arab Labor. Dif- ferences between the two authors are immediately apparent. More than perhaps any other writer, Oz represents the Zionist core of the political and literary establishment in Israel, as his autobiographical novel depicts one of the most important families in the early Israeli intelligentsia. Conversely, Kashua is a Palestinian Israeli and thus part of the most marginalized minority in Israeli society.1 I would like to complicate this picture of center and periphery by bringing out the major writer in Kashua and the minor writer in Oz. It is also my intention to expose the complimentary and reciprocal relations between the positions that they occupy. Thus, the article attempts to argue against a simple one-to-one correspondence between the centrality or marginal ity of an author's political position and the centrality or marginality of his or her literary en- deavors. In addition, both writers mobilize their own minority narrative and ap- peal to the traditional minority position of Judaism to bring about positive trans- formation. Amos Oz inhabits a special place in Hebrew literature. The most influential Hebrew writer in contemporary Israel and the best-selling Israeli author abroad, he is also a very influential political essayist and commentator. -

Margalit Halbertal Liberalism and the Right to Culture.Pdf

Liberalism and the Right to Culture Authors(s): AVISHAI MARGALIT and MOSHE HALBERTAL Source: Social Research, Vol. 61, No. 3, Liberalism (FALL 1994), pp. 491-510 Published by: The New School Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40971045 Accessed: 24-03-2016 19:06 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40971045?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The New School is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Social Research http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 137.110.74.76 on Thu, 24 Mar 2016 19:06:54 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Liberalism and the Right to BY AVISHAI MARGALIT Culture /. AND MOSHE HALBERTAL Setting Up the Problem JlTuman beings have a right to culture- not just any culture, but their own. The right to culture has far-reaching implications for the liberal conception of the state. A culture essentially requires a group, and the right to culture may involve giving groups a status that contradicts the status of the individual in a liberal state. -

On Modern Jewish Identities Moshe Halbertal

SHALOM HARTMAN ]DD שלום הרטמן institute On Modern Jewish Identities Moshe Halbertal 1. R. Mordechai Yaakov Breish, Responsa Helqat Ya'aqov, Yoreh De'ah §150 1 2. R. Ben-Zion Meir Hai Uziel, Responsa Pisqei Uziel be-She'elot ha-Zeman, §65 3 3. Maimonides, "Letter to Ovadyah the Convert" 5 4. Avi Sagi and Zvi Zohar, Transforming Identity: The Ritual Transformation from Gentile to Jew - Structure and Meaning, 268-296. 9 RTS 2016 1. R. Mordechai Yaakov Breish, Responsa Helqat Ya'aqov, Yoreh De’ah §150 שו״ת חלקת יעקב יורה דעה סימן קנ לענין גרים הבאים מחמת אישות כבוד הרב הגאון החריף ובקי טובא, איש האשכולות מ ר'רוכר וכףמנחם קירשבוים ראב״ד בפפד״מ. אחדשה״ט. ספרו הנשלח לי למנה, שו״ת "מנחם משיב" קבלתי לנכון ולאות תודה עיינתי בספרו, וראיתי שהאריך בשם בסימן מ״ב להתיר לקבל גרים הבאים מחמת אישות שבאם לא יקבלו אותם ילכו להרבנים הריפורמים שאין מדקדקים בטבילה ולא הוי גרים על פי דין כלל, לכן התיר לקבל אותם ויהי' עכ״פ גרים מדינא. ואף דמבואר בגמ' ורמב״ם ושו״ע דצריכין לבדוק שמא בשביל אשה בא, כיון דעכ״פ בדיעבד בכל אופן הוי גר, מוטב שיאכל בשר תמותות ואל יאכל בשר נבלות, וכל קוטב ההיתר דאל״כ ידור עמה כך באיסור או ע״י גירות הריפורמי, ויהי' נחשבים בקהל ישראל, ויטמעו בנו, והאריך שם. א( ואני אשתומם מאד על המראה - כי הרבנים היושבים בערי הפריצות במערב אירופא אין יכולים לרמאות את עצמן באשר יודעים בטוב, אשר רובא דרובא גרים כאלו, הם אשר נדבקו נפשם בישראל להתחתן ורוב הישראלים הללו הם פושעים ואין רוצים כלל לידע מיהדות כשרות שבת נדה, כל המצות הם עליהם למעמסה, והם רק יהודי לאומי, ויודעים בטח אשר גם הנכרית אשר למראית עין מתגיירת, לא תתנהג כלל בשום יהדות, כיון שגם בעלה היהודי הלאומי אינו יודע כלל מזה. -

Imah on the Bimah: Gender and the Roles of Latin American Conservative Congregational Rabinas Valeria N

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 3-29-2011 Imah on the Bimah: Gender and the Roles of Latin American Conservative Congregational Rabinas Valeria N. Schindler Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FI11042002 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Gender and Sexuality Commons, Other Religion Commons, Sociology of Culture Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Schindler, Valeria N., "Imah on the Bimah: Gender and the Roles of Latin American Conservative Congregational Rabinas" (2011). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 353. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/353 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida IMAH ON THE BIMAH: GENDER AND THE ROLES OF LATIN AMERICAN CONSERVATIVE CONGREGATIONAL RABINAS A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in RELIGIOUS STUDIES by Valeria Schindler 2011 To: Dean Kenneth Furton College of Arts and Sciences This thesis, written by Valeria Schindler, and entitled Imah on the Bimah: Gender and the Roles of Latin American Conservative Congregational Rabinas, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this thesis and recommend that it be approved. _______________________________________ Ana María Bidegain _______________________________________ Albert Wuaku _______________________________________ Oren Baruch Stier, Major Professor Date of Defense: March 29, 2011 The thesis of Valeria Schindler is approved. -

Course Syllabus

THE TIKVAH FUND 165 E. 56th Street New York, New York 10022 Reason, Revelation, and Jewish Thought July 28, 2014 – August 1, 2014 Dean: Daniel Mark Instructor: Moshe Halbertal I. Description Is reason a sovereign authority in the realms of morality and metaphysics? Led by the prominent philosopher Moshe Halbertal, we will explore this question through Biblical, Rabbinic, and Medieval Jewish texts. In the realm of independent moral reasoning we will examine texts and traditions—mainly midrashic and Talmudic—that deal with two questions: 1. Is there recognition of independent moral obligation outside of revelation within Jewish tradition? 2. What is the role of value judgments in halakhic interpretation? Or to put it differently, in what way do values, integrated into the interpretive processes that are the heart of classical Jewish thought, impact the direction of Jewish law? We will address as well the realm of beliefs and metaphysics, mainly examining the different ways in which Jewish philosophy located the role of reason in shaping and orienting faith. This issue will be dealt with by reading Maimonides’ Guide, and the controversy that evolved around Maimonides positions. THE TIKVAH FUND 165 E. 56th Street New York, New York 10022 II. Course Calendar: July 28th: The Place of Independent Ethical Consideration Derived from Reason and their Place within Revelation and Halakhah, part 1 9:30 AM – 12:30 PM Readings: • Commentary of Nachmanides, Genesis 6:13 • Commentary of Nachmanides, Deuteronomy 6:18 • Rav Aharon Lichtenstein, “Does Judaism Recognize an Ethic Independent of Halakhah” in Leaves of Faith: The World of Jewish Living Volume II (United States: Ktav Publishing House, 2004) pp. -

Curriculum Vita

CURRICULUM VITA W. COLE DURHAM, JR. Susa Young Gates University Professor of Law and Director, International Center for Law and Religion Studies at BYU J. Reuben Clark Law School, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah 84602 USA Phone: (801) 422-6842 Fax: (801) 422-0399 Email: [email protected] EDUCATION: A.B., Harvard College, 1972 (Magna Cum Laude in Philosophy); J.D., Harvard Law School, 1975 (Cum Laude); Note Editor, Harvard Law Review; Managing Editor, Harvard International Law Journal. PROFESSIONAL SERVICE: Teaching: Director International Center for Law and Religion Studies at Brigham Young University (2000-Present). Professor of Law J. Reuben Clark Law School, 1983-Present Brigham Young University (Asst. and Assoc. Prof. 1976-83). Susa Young Gates University Professor of Law since 1999. Visiting Professor University of Vienna, Faculty of Law, Spring, 2004. Recurring Visiting Legal Studies Department, Central European University, Budapest, Professor of Law Hungary, Spring 1994-present. (Courses on Comparative Law of Religious Freedom and Comparative Constitutional Law). Guest Professor Mainz, Germany, 1984. Editorial and Board Positions, Community Service Member of the Honorary Committee of the International Association for the Defense of Religious Liberty and Member of the Consultative Committee-Board of Experts of Conscience and Liberty Magazine (July 2012-present). President, International Consortium for Law and Religion Studies (September 2011-Present; Vice President from March 2007-September 2011). Co-Editor-in-Chief of the Oxford Journal of Law and Religion (May 2011-Present). Member, International Advisory Board for the G.P. Koirala Center, Kathmandu, Nepal (May 2011-Present). -1- Member, Editorial Board of Review Dionysiana, University Ovidius Constanta Romania (December 2009-Present). -

Willy Fautré

Willy Fautré Director of Human Rights Without Frontiers Int. (Brussels) Prof. of Germanic languages Director of the Phare Democracy Programme “Religious Minorities in Albania, Bulgaria and Romania” (1995-1996) Chargé de mission at the Belgian Parliament (1989-1990) Chargé de mission at the Cabinet of the Ministry of Education (1984-1985) Researcher, University of Mons Author of the book “Nos Prisonniers du Goulag” (120 p.), ACES, Verviers Author of numerous articles and contributions to books on freedom of religion: Non-State Actors and Religious Freedom in Europe, 2006, by James Lance, Editor and Associate Publisher, Kumarian Press, 1294 Blue Hills Avenue Bloomfield, CT 06002, USA Belgium’s Anti-Sect Policy, in Regulating Religion: Case Studies from Around the Globe, ed. James T. Richardson, Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, 2004 Sects: Do democracies need laws of exception? The Belgian experience, Fides et Libertas 2004, pp 29-40, ed. IRLA The Sect Issue in the European Francophone Sphere, Facilitating Freedom of Religion or Belief: A Deskbook, Tore Lindholm, W. Cole Durham Jr and Bahia G. Tahzib-Lie (eds.), Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, Leiden, 2004, pp 595-618 Religiöse Freiheit, Diskriminierungen und Intoleranz in der Europäischen Union/ Österreich 2003-2004, 32 p, Human Rights Without Frontiers Int., Brussels, 2004 Belgium, Entry in Religions of the World, A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices, J. Gordon Melton and Martin Baumann (eds.), ABC-CLIO Inc., Santa Barbara, 2002 Religious freedom, intolerance and discrimination in the EU: Belgium 2002-2003, 12 p, Human Rights Without Frontiers Int., Brussels, 2003 The Protection of Religious Minorities in Belgium: A Western European Perspective, Protecting the Human Rights of Religious Minorities in Eastern Europe, Peter G.