Mikhail Busch's Master's Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Novalis's Magical Idealism

Symphilosophie International Journal of Philosophical Romanticism Novalis’s Magical Idealism A Threefold Philosophy of the Imagination, Love and Medicine Laure Cahen-Maurel* ABSTRACT This article argues that Novalis’s philosophy of magical idealism essentially consists of three central elements: a theory of the creative or productive imagination, a conception of love, and a doctrine of transcendental medicine. In this regard, it synthesizes two adjacent, but divergent contemporary philosophical sources – J. G. Fichte’s idealism and Friedrich Schiller’s classicism – into a new and original philosophy. It demonstrates that Novalis’s views on both magic and idealism, not only prove to be perfectly rational and comprehensible, but even more philosophically coherent and innovative than have been recognised up to now. Keywords: magical idealism, productive imagination, love, medicine, Novalis, J. G. Fichte, Schiller RÉSUMÉ Cet article défend l’idée selon laquelle trois éléments centraux composent ce que Novalis nomme « idéalisme magique » pour désigner sa philosophie propre : la conception d’une imagination créatrice ou productrice, une doctrine de l’amour et une théorie de la médecine transcendantale. L’idéalisme magique est en cela la synthèse en une philosophie nouvelle et originale de deux sources philosophiques contemporaines, à la fois adjacentes et divergentes : l’idéalisme de J. G. Fichte et le classicisme de Friedrich Schiller. L’article montre que les vues de Novalis tant sur la magie que sur l’idéalisme sont non seulement réellement rationnelles et compréhensibles, mais philosophiquement plus cohérentes et novatrices qu’on ne l’a admis jusqu’à présent. Mots-clés : idéalisme magique, imagination productrice, amour, médecine, Novalis, J. G. -

Network Map of Knowledge And

Humphry Davy George Grosz Patrick Galvin August Wilhelm von Hofmann Mervyn Gotsman Peter Blake Willa Cather Norman Vincent Peale Hans Holbein the Elder David Bomberg Hans Lewy Mark Ryden Juan Gris Ian Stevenson Charles Coleman (English painter) Mauritz de Haas David Drake Donald E. Westlake John Morton Blum Yehuda Amichai Stephen Smale Bernd and Hilla Becher Vitsentzos Kornaros Maxfield Parrish L. Sprague de Camp Derek Jarman Baron Carl von Rokitansky John LaFarge Richard Francis Burton Jamie Hewlett George Sterling Sergei Winogradsky Federico Halbherr Jean-Léon Gérôme William M. Bass Roy Lichtenstein Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael Tony Cliff Julia Margaret Cameron Arnold Sommerfeld Adrian Willaert Olga Arsenievna Oleinik LeMoine Fitzgerald Christian Krohg Wilfred Thesiger Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant Eva Hesse `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas Him Mark Lai Clark Ashton Smith Clint Eastwood Therkel Mathiassen Bettie Page Frank DuMond Peter Whittle Salvador Espriu Gaetano Fichera William Cubley Jean Tinguely Amado Nervo Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay Ferdinand Hodler Françoise Sagan Dave Meltzer Anton Julius Carlson Bela Cikoš Sesija John Cleese Kan Nyunt Charlotte Lamb Benjamin Silliman Howard Hendricks Jim Russell (cartoonist) Kate Chopin Gary Becker Harvey Kurtzman Michel Tapié John C. Maxwell Stan Pitt Henry Lawson Gustave Boulanger Wayne Shorter Irshad Kamil Joseph Greenberg Dungeons & Dragons Serbian epic poetry Adrian Ludwig Richter Eliseu Visconti Albert Maignan Syed Nazeer Husain Hakushu Kitahara Lim Cheng Hoe David Brin Bernard Ogilvie Dodge Star Wars Karel Capek Hudson River School Alfred Hitchcock Vladimir Colin Robert Kroetsch Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai Stephen Sondheim Robert Ludlum Frank Frazetta Walter Tevis Sax Rohmer Rafael Sabatini Ralph Nader Manon Gropius Aristide Maillol Ed Roth Jonathan Dordick Abdur Razzaq (Professor) John W. -

Concepts of Spirituality in 'Th Works of Robert Houle and Otto Rogers Wxth Special Consideration to Images of the Land

CONCEPTS OF SPIRITUALITY IN 'TH WORKS OF ROBERT HOULE AND OTTO ROGERS WXTH SPECIAL CONSIDERATION TO IMAGES OF THE LAND Nooshfar B, Ahan, BCom A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial filfillment of the requïrements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Art History Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario 6 December 2000 O 2000, Nooshfar B. Ahan Bibliothéque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibIiographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada your me voue rélèreoca Our file Notre reMrence The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microfomq vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fkom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. This thesis examines the use of landscape motifs by two contemporary Canadian artists to express their spiritual aspirations. Both Robert Houle and Otto Rogers, inspired by the Canadian prairie landscape, employ its abstracted form to convey their respective spiritual ideas. -

2. Very Little Almost Nothing Simon Critchley

Unworking romanticism America, to which I shall return in my discussion of Cavell. It is rather the offer of a new way of inhabiting this place, at this time, a place that Stevens names, in his last poem and piece of prose, ‘the spare region of Connecticut’ , a place inhabited after the time when mythology was possible.51 As Stevens puts it: A mythology reflects its region. Here In Connecticut, we never lived in a time When mythology was possible. Without mythology we are offered the inhabitation of this autumnal or wintry sparseness, this Connecticut, what Stevens calls ‘a dwindled sphere’: The proud and the strong Have departed. Those that are left are the unaccomplished, The finally human, Natives of a dwindled sphere. (CP 504) ‘A dwindled sphere’…this is very little, almost nothing. Yet, it is here that we become ‘finally human natives’. (c) Romantic ambiguity The limping of philosophy is its virtue. True irony is not an alibi; it is a task; and the very detachment of the philosopher assigns to him a certain kind of action among men.52 Romanticism fails. We have already seen how the project of Jena Romanticism is riddled with ambiguity. On the one hand, romanticism is an aesthetic absolutism, where the aesthetic is the medium in which the antinomies of the Kantian system— and the Enlightenment itself—are absolved and overcome. For Schlegel, the aesthetic or literary absolute would have the poetic form of the great novel of the modern world, the Bible of secularized modernity. However, on the other hand, the audacity of romantic naïveté goes together with the experience of failure and incompletion: the great romantic novel of the modern world is never written, and the romantic project can be said to fail by internal and external criteria. -

Mppwp1 2019 SR

The Aesthetic Turn The Cultivation and Propagation of Aesthetic Experience after its Declaration of Independence Raffnsøe, Sverre Document Version Final published version Publication date: 2019 License CC BY-NC-ND Citation for published version (APA): Raffnsøe, S. (2019). The Aesthetic Turn: The Cultivation and Propagation of Aesthetic Experience after its Declaration of Independence. Department of Management, Politics and Philosophy, CBS. MPP Working Paper No. 2019/1 Link to publication in CBS Research Portal General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us ([email protected]) providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 26. Sep. 2021 Porcelænshaven 18B DK-2000 Frederiksberg T: +45 3815 3636 E: [email protected] cbs.dk/mpp facebook.com/mpp.cbs twitter.com/MPPcbsdk THE AESTHETIC TURN The Cultivation and Propagation of Aesthetic Experience after its Declaration of Independence Sverre Raffnsøe Department of Management, Politics and Philosophy Copenhagen Business School Working paper no [1] - 2019 MPP WORKING PAPER ISBN: 978-87-91839-39-9 2 The Aesthetic Turn The Cultivation and Propagation of Aesthetic Experience after its Declaration of Independence Sverre Raffnsøe Table of Contents I. The genie of aestheticism .......................................................................................................................... 3 II. Aesthetic transitions .................................................................................................................................. 5 III. The normative ‘poetic’ approach to aesthetics in Plato, Baumgarten and Boileau ............................. -

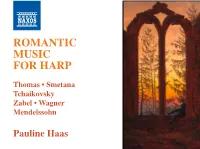

Romantic Music for Harp

ROMANTIC MUSIC FOR HARP Thomas • Smetana Tchaikovsky Zabel • Wagner Mendelssohn Pauline Haas 1 The Vision of a Dreamer by Pauline Haas A troubling landscape, the remains of an abbey, or maybe of a castle – the horizon in the distance stands out against the dusk. In the middle of the ruins, in the frame of an unglazed window, a young man is seated in profile. Is he dreaming? Is he doubting? Is he believing? The Dreamer is a journey of initiation: it is about Man travelling down his path of life pursued by his double, it is about an artist in pursuit of truth. I have contemplated this painting, seeing in it my own image as though in a mirror. I have created the image of this individual as a picture of my own dreams. I was his age when I made this recording – the age when one leaves childhood behind to enter the wider world and face up to oneself. I became conscious that the instrument lying against my shoulder, which had inspired so many poets and artists, but had been abandoned by musicians was, in my hands, like a blank page. I placed on my music stand, therefore, the traditional repertoire for the harp, other works considered inaccessible for the harpist, works which had long maintained a magical impact on me. I have woven a connecting thread between these works, nuancing the virgin whiteness of my page without managing to reach all the possible heights. Like a figure in a painting by Caspar David Friedrich this programme contemplates a distant horizon. -

The Landscape of Longing

Caspar David Friedrich^ the peculiar Romantic. The Landscape of Longing BY ANNE HOLLANDER nly nine oil paintings and exhibition de\oted t(.> Friedricb ever to ticeable thing abotit this mini-retro- eleven works on paper be moimted in tbis coiuitiy. It is possible spective is its consistency. Friedrich iiKikc lip the Metropolitan that many more Friedricbs still lurk in perfected his method by 1808 and O Mtiseiiin's current exhibi- the Soviet Union, unknown in tbe West, never changed it, even dining the peri- tion of Caspar David Fricdricli's works even in repiodnction; but for now we are od after his stroke in 1835, wben he from Russia; and thev are only mininiallv gi'eatly pleased to see these. worked very little. augmeiilfd by a lew engravings, owned They are few, and many are ver\' Friedricb never dated bis paintings, by ibe niiist'uin. wliicb were made by ibe small, aitbotigb two of tbem, meastir- and lie sbowed none of tbat obsession artist's brotber from some with development so com- of Friedricb's 180:i draw- mon to artists of his peri- ings. Housed far to the od and to others ever rear of tbe main floor in a since. Apparently lie bad small section ol tbe I.eb- no need to enact a \isible man wing, this sbow must figbt for artistic teriitorA, be sotiglit otit, but it is im- to be seen to be struggling portant despite its small steadily along insicle the si/e and ascetic Haxor. C.as- meditmi itself, to give per- par David Friedricb (I 774- pettial evidence of bis per- 1H40) is now generally ac- sonal battle witb tbe in- knowledged as a great tractable eye, tbe pesky Romantic painter, and materials, tbe superior predecessors, (he pre.sent space lias been made for ri\als, with aljiding artistic bim beside I inner, (ieri- problems and new selt- cault, Blake, and Goya on imposed technical tasks, tbe roster of Eaily Nine- vvitli dominant opinion, teenth Centnry Originals. -

Political Imagination in German Romanticism John Thomas Gill

Wild Politics : Political Imagination in German Romanticism John Thomas Gill A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Ph.D in the Department of Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures in the College of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: Gabriel Trop Eric Downing Stefani Engelstein Jakob Norberg Aleksandra Prica i © 2020 John Thomas Gill ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT John Gill: Wild Politics : Political Imagination in German Romanticism (Under the direction of Gabriel Trop) The political discourse of German Romanticism is often interpreted reductively: as either entirely revolutionary, reactionary, or indeed apolitical in nature. Breaking with this critical tradition, this dissertation offers a new conceptual framework for political Romanticism called wild politics . I argue that Romantic wild politics generates a sense of possibility that calls into question pragmatic forms of implementing sociopolitical change; it envisions imaginative alternatives to the status quo that exceed the purview of conventional political thinking. Three major fields of the Romantic political imaginary organize this reading: affect, nature, and religion. Chapter 1 examines Novalis’ politics of affect. In his theory of the fairy tale—as opposed to the actual fairy tales he writes—Novalis proposes a political paradigm centered on the aesthetic dimension of love. He imagines a new Prussian state constituted by emotional attachments between the citizen and the monarch. Chapter 2 takes up the “new mythology” in the works of F.W.J. Schelling, Friedrich Schlegel, and Johann Wilhelm Ritter, the comprehensive project of reorienting modern life towards its most transformative potentials. -

An Eye for Landscapes That Transcend Nature,” the New York Times, May 22, 2009

Genocchio, Benjamin. “An Eye for Landscapes That Transcend Nature,” The New York Times, May 22, 2009. An Eye for Landscapes That Transcend Nature One’s lasting impression of the April Gornik exhibition at the Heckscher Museum of Art in Huntington is the sheer virtuosity of the pictures. They glow with mystery and grandeur. Landscape painting of this quality is not often seen on Long Island. Assembled by Kenneth Wayne, the museum’s chief curator, the show focuses on the artist’s powerful, large-scale oil paintings. There are a dozen pictures, created roughly from the late 1980s to the present, nicely displayed in two of the Heckscher’s newly renovated galleries. The removal of a false ceiling in them has allowed the museum to accommodate much larger works than it could before. New Horizons. The large-scale oil paintings by April Gornik on display at the Heckscher include “Sun Storm Sea” (2005). At 56, Ms. Gornik is already a painter of eminence. She has had shows around the world, and her work is in several major museum collections, including those of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art. I would place her among the top landscape artists working in America today. That this is Ms. Gornik’s first major solo exhibition on Long Island in more than 15 years seems an oversight, especially given that she lives part of the year in Suffolk County. But better late than never, for there are probably dozens of artists living and working on Long Island who are deserving of shows. -

Humanities (World Focus) Course Outline

Guiding Document: Humanities Course Outline Humanities (World Focus) Course Outline The Humanities To study humanities is to look at humankind’s cultural legacy-the sum total of the significant ideas and achievements handed down from generation to generation. They are not frivolous social ornaments, but rather integral forms of a culture’s values, ambitions and beliefs. UNIT ONE-ENLIGHTENMENT AND COMPARATIVE GOVERNMENTS (18th Century) HISTORY: Types of Governments/Economies, Scientific Revolution, The Philosophes, The Enlightenment and Enlightenment Thinkers (Hobbes, Locke, Montesquieu, Voltaire, Jefferson, Smith, Beccaria, Rousseau, Franklin, Wollstonecraft, Hidalgo, Bolivar), Comparing Documents (English Bill of Rights, A Declaration of the Rights of Man, Declaration of Independence, US Bill of Rights), French Revolution, French Revolution Film, Congress of Vienna, American Revolution, Latin American Revolutions, Napoleonic Wars, Waterloo Film LITERATURE: Lord of the Flies by William Golding (summer readng), Julius Caesar by Shakespeare (thematic connection), Julius Caesar Film, Neoclassicism (Denis Diderot’s Encyclopedie excerpt, Alexander Pope’s “Essay on Man”), Satire (Oliver Goldsmith’s Citizen of the World excerpt, Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels excerpt), Birth of Modern Novel (Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe excerpt), Musician Bios PHILOSOPHY: Rene Descartes (father of philosophy--prior to time period), Philosophes ARCHITECTURE: Rococo, Neoclassical (Jacques-Germain Soufflot’s Pantheon, Jean- Francois Chalgrin’s Arch de Triomphe) -

Artificial Infinity

Artificial Infinity Artificial Infinity From Caspar David Friedrich to Notch m Xavier Belanche Translated by Elisabeth Cross An Epic Fail This book was typeset using the LATEX typesetting system originally developed by Leslie Lamport, based on TEX created by Donald Knuth. Typographical decisions were based on the recommendations given in The Elements of Typographic Style by Bringhurst. The picture of the logo is No. 1 from the Druidical Antiquities from the book The Antiquities of England and Wales (1783) by Francis Grose. The picture on the frontpage is Round Tower of Donoughmore from the book Old England: A Pictorial Museum (1845) by Charles Knight. The picture is The image is from Donaghmore, a small cemetery near Navan in co. Meath. Google Maps: 53.670848, -6.661248 (+53° 39’ 49.55", -6° 40’ 11.96"). Those pictures are out of copyright (called public domain in the USA) and were found at Liam Quin's oldbooks.org The text font is Bergamo. Contents Introduction 1 Abysm 5 Tree 15 Bibliography 29 Artificial Infinity From Caspar David Friedrich to Notch Introduction The idea of a hypothetical continuity and the survival of ro- mantic landscape in the context of a few video games primar- ily originates from how the videogame creators conceive and express Nature from a profoundly personal point of view. As a result, the demonstration of the possible coincidences and analogies between Caspar David Friedrich’s painting and the representation of Nature in Minecra has become such a fasci- nating issue which is impossible to ignore. When I was giving shape to the concept, the reading of the essays Robert Rosenblum dedicated to the validity of roman- ticism in the works of those artists on the periphery of modern art such as Vincent Van Gogh, Edvard Munch, Piet Mondrian and Mark Rothko, helped me pinpoint some common refer- ences to those painters who share a romantic attraction to a Nature alienated from mankind. -

AITKEN Leonard Thesis

Time Unbound: An Exploration of Eternity in Twentieth- Century Art. c. Leonard Aitken 2014 Time Unbound: An Exploration of Eternity in Twentieth- Century Art. SUBMISSION OF THESIS TO CHARLES STURT UNIVERSITY: Degree of Master of Arts (Honours) CANDIDATE’S NAME: Leonard Aitken QUALIFICATIONS HELD: Degree of Master of Arts Practice (Visual Arts), Charles Sturt University, 2011 Degree of Bachelor of Arts (Visual Arts), Charles Sturt University, 1995 FULL TITLE OF THESIS: Time Unbound: An Exploration of Eternity in Twentieth-Century Art. MONTH AND YEAR OF SUBMISSION: June 2014 Time Unbound: An Exploration of Eternity in Twentieth- Century Art. SUBMISSION OF THESIS TO CHARLES STURT UNIVERSITY: Degree of Master of Arts (Honours) ABSTRACT The thesis examines contemporary works of art which seek to illuminate, describe or explore the concept of ‘eternity’ in a modern context. Eternity is an ongoing theme in art history, particularly from Christian perspectives. Through an analysis of artworks which regard eternity with intellectual and spiritual integrity, this thesis will explain how the interpretation of ‘eternity’ in visual art of the twentieth century has been shaped. It reviews how Christian art has been situated in visual culture, considers its future directions, and argues that recent forms are expanding our conception of this enigmatic topic. In order to establish how eternity has been addressed as a theme in art history, the thesis will consider how Christian art has found a place in Western visual culture and how diverse influences have moulded the interpretation of eternity. An outline of a general cosmology of eternity will be treated and compared to the character of time in the material world.