Community-Based Deer Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Management of Arthropod Pathogen Vectors in North America: Minimizing Adverse Effects on Pollinators

Journal of Medical Entomology, 2017, 1–13 doi: 10.1093/jme/tjx146 Forum Forum Management of Arthropod Pathogen Vectors in North America: Minimizing Adverse Effects on Pollinators Howard S. Ginsberg,1,2 Timothy A. Bargar,3 Michelle L. Hladik,4 and Charles Lubelczyk5 1USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, University of Rhode Island, RI Field Station, Woodward Hall – PSE, Kingston, RI 02881 ([email protected]), 2Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected], 3USGS Wetland and Aquatic Research Center, 7920 NW 71st St., Gainesville, FL 32653 ([email protected]), 4USGS California Water Science Center, 6000 J St., Placer Hall, Sacramento, CA 95819 ([email protected]), and 5Maine Medical Center Research Institute, Vector-Borne Disease Laboratory, 81 Research Dr., Scarborough, ME 04074 ([email protected]) Subject Editor: Lars Eisen Received 26 April 2017; Editorial decision 19 June 2017 Abstract Tick and mosquito management is important to public health protection. At the same time, growing concerns about declines of pollinator species raise the question of whether vector control practices might affect pollinator populations. We report the results of a task force of the North American Pollinator Protection Campaign (NAPPC) that examined potential effects of vector management practices on pollinators, and how these pro- grams could be adjusted to minimize negative effects on pollinating species. The main types of vector control practices that might affect pollinators are landscape manipulation, biocontrol, and pesticide applications. Some current practices already minimize effects of vector control on pollinators (e.g., short-lived pesticides and application-targeting technologies). Nontarget effects can be further diminished by taking pollinator protection into account in the planning stages of vector management programs. -

Appendix E: Alternatives Analysis Report Integrated Mosquito and Vector Management Program

Integrated Mosquito and Vector Management Program APPENDIX E ALTERNATIVES ANALYSIS REPORT Appendix E: Alternatives Analysis Report Integrated Mosquito and Vector Management Program Document Information Prepared by Napa County Mosquito Abatement District Project Name Integrated Mosquito and Vector Management Program Draft Programmatic Environmental Impact Report Date July 2014 Prepared by: Napa County Mosquito Abatement District 15 Melvin Road, American Canyon, CA 94503 USA www.napamosquito.org With assistance from Cardno ENTRIX 2300 Clayton Road, Suite 200, Concord, CA 94520 USA www.cardno.com July 2014 NCMAD Document Information i MVCAC DPEIR_APP E_NCMAD AltRpt_MAR2016_R2.docx Appendix E: Alternatives Analysis Report Integrated Mosquito and Vector Management Program This Page Intentionally Left Blank ii Document Information NCMAD July 2014 MVCAC DPEIR_APP E_NCMAD AltRpt_MAR2016_R2.docx Appendix E: Alternatives Analysis Report Integrated Mosquito and Vector Management Program Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................1-1 1 Program Background ....................................................................................................1-1 1.1 Program Location ............................................................................................................. 1-1 1.2 Program History ................................................................................................................ 1-1 2 Potential Tools...............................................................................................................2-1 -

Checklist of British and Irish Hymenoptera - Chalcidoidea and Mymarommatoidea

Biodiversity Data Journal 4: e8013 doi: 10.3897/BDJ.4.e8013 Taxonomic Paper Checklist of British and Irish Hymenoptera - Chalcidoidea and Mymarommatoidea Natalie Dale-Skey‡, Richard R. Askew§‡, John S. Noyes , Laurence Livermore‡, Gavin R. Broad | ‡ The Natural History Museum, London, United Kingdom § private address, France, France | The Natural History Museum, London, London, United Kingdom Corresponding author: Gavin R. Broad ([email protected]) Academic editor: Pavel Stoev Received: 02 Feb 2016 | Accepted: 05 May 2016 | Published: 06 Jun 2016 Citation: Dale-Skey N, Askew R, Noyes J, Livermore L, Broad G (2016) Checklist of British and Irish Hymenoptera - Chalcidoidea and Mymarommatoidea. Biodiversity Data Journal 4: e8013. doi: 10.3897/ BDJ.4.e8013 Abstract Background A revised checklist of the British and Irish Chalcidoidea and Mymarommatoidea substantially updates the previous comprehensive checklist, dating from 1978. Country level data (i.e. occurrence in England, Scotland, Wales, Ireland and the Isle of Man) is reported where known. New information A total of 1754 British and Irish Chalcidoidea species represents a 22% increase on the number of British species known in 1978. Keywords Chalcidoidea, Mymarommatoidea, fauna. © Dale-Skey N et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. 2 Dale-Skey N et al. Introduction This paper continues the series of checklists of the Hymenoptera of Britain and Ireland, starting with Broad and Livermore (2014a), Broad and Livermore (2014b) and Liston et al. -

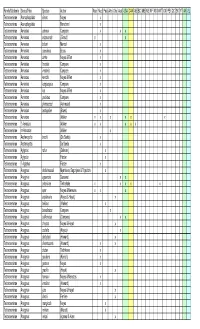

Encyrtidae Walker X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X

Family/Subfamily Genus/Tribe Species Author Near Neot Pala Afro Orie Aust USA CAN AB BC MB NB NF NS NWT ON PEI QC SK YT AK GL Tetracneminae Acerophagoides almon Noyes x Tetracneminae Acerophagoides Blanchard x Tetracneminae Aenasius advena Compere x x x Tetracneminae Aenasius arizonensis (Girault) x x Tetracneminae Aenasius bolowi Mercet x Tetracneminae Aenasius caeruleus Brues x Tetracneminae Aenasius cirrha Noyes & Ren x Tetracneminae Aenasius frontalis Compere x Tetracneminae Aenasius insularis Compere x Tetracneminae Aenasius kerrichi Noyes & Ren x Tetracneminae Aenasius longiscapus Compere x Tetracneminae Aenasius lua Noyes & Ren x Tetracneminae Aenasius paulistus Compere x Tetracneminae Aenasius phenacocci (Ashmead) x Tetracneminae Aenasius tachigaliae (Brues) x Tetracneminae Aenasius Walker x x x x x x Tetracneminae ? Aenasius Walker x x x x x Tetracneminae nr Aenasius Walker x Tetracneminae Aeptencyrtus bruchi (De Santis) x Tetracneminae Aeptencyrtus De Santis x Tetracneminae Aglyptus rufus (Dalman) x Tetracneminae Aglyptus Förster x Tetracneminae ? Aglyptus Förster x Tetracneminae Anagyrus abdulrassouli Myartseva, Sugonjaev & Trjapitzin x Tetracneminae Anagyrus agraensis Saraswat x x Tetracneminae Anagyrus antoninae Timberlake x x x x x Tetracneminae Anagyrus aper Noyes & Menezes x x x Tetracneminae Anagyrus aquilonaris (Noyes & Hayat) x Tetracneminae Anagyrus belibus (Walker) x Tetracneminae Anagyrus beneficians Compere x Tetracneminae Anagyrus californicus (Compere) x x Tetracneminae Anagyrus chrysos Noyes & Hayat x Tetracneminae -

Review Article Potential of Traditional Knowledge of Plants in the Management of Arthropods in Livestock Industry with Focus on (Acari) Ticks

Hindawi Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine Volume 2017, Article ID 8647919, 33 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/8647919 Review Article Potential of Traditional Knowledge of Plants in the Management of Arthropods in Livestock Industry with Focus on (Acari) Ticks Wycliffe Wanzala1,2 1 Department of Biological Sciences, School of Science and Information Sciences, Maasai Mara University, P.O.Box861-20500,Narok,Kenya 2Behavioural and Chemical Ecology Department, International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology, African Insect Science for Food and Health, P.O. Box 30772-00100-GPO, Nairobi, Kenya Correspondence should be addressed to Wycliffe Wanzala; [email protected] Received 19 December 2016; Accepted 11 May 2017; Published 17 July 2017 Academic Editor: Jose´ L. Rios Copyright © 2017 Wycliffe Wanzala. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Antitick plants and related ethnoknowledge/ethnopractices with potential for integrated tick control and management strategies to improve livestock production are reviewed. About 231 plants reviewed showed a variety of bioactive properties, namely, being toxic, repellent, antifeedant, and antiovipositant and ability to immobilize target tick species. These ethnobotanical substances are potentially useful in developing sustainable, efficient, and effective antitick agents suitable for rural livestock farmers. -

Tripartite Interactions Among Ixodiphagus Hookeri, Ixodes Ricinus and Deer: Differential Interference with Transmission Cycles of Tick-Borne Pathogens

pathogens Article Tripartite Interactions among Ixodiphagus hookeri, Ixodes ricinus and Deer: Differential Interference with Transmission Cycles of Tick-Borne Pathogens Aleksandra I. Krawczyk 1,2, Julian W. Bakker 2 , Constantianus J. M. Koenraadt 2 , Manoj Fonville 1, Katsuhisa Takumi 1, Hein Sprong 1,* and Samiye Demir 3,* 1 Centre for Infectious Disease Control, National Institute for Public Health and the Environment, Antonie van Leeuwenhoeklaan 9, 3721 MA Bilthoven, The Netherlands; [email protected] (A.I.K.); [email protected] (M.F.); [email protected] (K.T.) 2 Laboratory of Entomology, Wageningen University & Research, 6708PB Wageningen, The Netherlands; [email protected] (J.W.B.); [email protected] (C.J.M.K.) 3 Zoology Section, Department of Biology, Ege University Faculty of Science, Bornova Izmir 35040, Turkey * Correspondence: [email protected] (H.S.); [email protected] (S.D.) Received: 1 April 2020; Accepted: 29 April 2020; Published: 30 April 2020 Abstract: For the development of sustainable control of tick-borne diseases, insight is needed in biological factors that affect tick populations. Here, the ecological interactions among Ixodiphagus hookeri, Ixodes ricinus, and two vertebrate species groups were investigated in relation to their effects on tick-borne disease risk. In 1129 questing ticks, I. hookeri DNA was detected more often in I. ricinus nymphs (4.4%) than in larvae (0.5%) and not in adults. Therefore, we determined the infestation rate of I. hookeri in nymphs from 19 forest sites, where vertebrate, tick, and tick-borne pathogen communities had been previously quantified. We found higher than expected co-occurrence rates of I. -

Assessment and Management of Vector Tick Populations in New Jersey

ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT OF VECTOR TICK POPULATIONS IN NEW JERSEY Terry L. Schulze and Robert A. Jordan A Guide for Pest Management Professionals, Land Managers, and Public Health Officials FREEHOLD TOWNSHIP HEALTH DEPARTMENT ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Preparation and publication of this manual was funded through Cooperative Agreements (1 U01 CI000172-01,02,03) between the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the New Jersey Department of Health and Senior Services (NJDHSS), and Health Service Grants (04,05,06-24-LYM-L-1) between the NJDHSS and the Freehold Area Health Department (FAHD). The authors thank Dr. Joseph Piesman (CDC, Fort Collins, Colorado), Dr. Faye E. Sorhage (NJDHSS, Trenton, New Jersey), Dr. George C. Hamilton (Rutgers Cooperative Extension, New Brunswick, New Jersey), Dr. Kirby C. Stafford III (Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station [CAES], New Haven, Connecticut), Dr. J. Mathews Pound (United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service [USDA, ARS], Kerrville, Texas), and Sean P. Healy (Monmouth County Mosquito Extermination Commission [MCMEC], Tinton Falls, New Jersey) for their critical review of this manual. We appreciate the contributions and support of the NJDHSS, particularly the professional and administrative staff of the Infectious and Zoonotic Diseases Program, on this and other projects. Appreciation is also extended to the Mayor, Committee, and Administration of Freehold Township, especially Margaret B. Jahn, for their continued support of tick-borne disease research and education. We also thank the various individuals, firms, and agencies for providing some of the photographs used in this manual. Cover: Female blacklegged tick, Ixodes scapularis, courtesy of Terry L. Schulze DISCLAIMER Mention of a product or company is for informational purposes only and does not constitute an endorsement by the authors and/or funding agencies. -

Ixodiphagus Hookeri and Its Wolbachia Symbionts in Ticks in the Netherlands Ellen Tijsse-Klasen1, Marieta Braks1, Ernst-Jan Scholte2 and Hein Sprong1*

Tijsse-Klasen et al. Parasites & Vectors 2011, 4:228 http://www.parasitesandvectors.com/content/4/1/228 RESEARCH Open Access Parasites of vectors - Ixodiphagus hookeri and its Wolbachia symbionts in ticks in the Netherlands Ellen Tijsse-Klasen1, Marieta Braks1, Ernst-Jan Scholte2 and Hein Sprong1* Abstract Background: Ixodiphagus hookeri is a parasitic wasp of ixodid ticks around the world. It has been studied as a potential bio-control agent for several tick species. We suspected that the presence of Wolbachia infected I. hookeri eggs in ticks is responsible for incidental detection of Wolbachia DNA in tick samples. Methods: The 28S rRNA and 16S rRNA genes of a specimen of I. hookeri was amplified and sequenced. PCR on part of the 28S rRNA gene was used to detect parasitic wasp DNA in 349 questing Ixodes ricinus ticks from various sampling sites. Furthermore, the wsp gene of Wolbachia was sequenced from the I. hookeri specimen and a subset of ticks was tested using this marker. Results: Several sequences from tick specimens were identical to the Wolbachia sequence of the I. hookeri specimen. Ixodiphagus hookeri was detected in 9.5% of all tested ticks, varying between 4% and 26% depending on geographic location. Ten out of eleven sampling sites throughout the Netherlands were positive for I. hookeri. Eighty-seven percent of I. hookeri-positive but only 1.6% of I. hookeri-negative ticks were Wolbachia positive. Detection of I. hookeri DNA was strongly associated with the detection of Wolbachia in ticks. Conclusion: This is the first reported case of I. hookeri in the Netherlands. -

Drosophila | Other Diptera | Ephemeroptera

NATIONAL AGRICULTURAL LIBRARY ARCHIVED FILE Archived files are provided for reference purposes only. This file was current when produced, but is no longer maintained and may now be outdated. Content may not appear in full or in its original format. All links external to the document have been deactivated. For additional information, see http://pubs.nal.usda.gov. United States Department of Agriculture Information Resources on the Care and Use of Insects Agricultural 1968-2004 Research Service AWIC Resource Series No. 25 National Agricultural June 2004 Library Compiled by: Animal Welfare Gregg B. Goodman, M.S. Information Center Animal Welfare Information Center National Agricultural Library U.S. Department of Agriculture Published by: U. S. Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service National Agricultural Library Animal Welfare Information Center Beltsville, Maryland 20705 Contact us : http://awic.nal.usda.gov/contact-us Web site: http://awic.nal.usda.gov Policies and Links Adult Giant Brown Cricket Insecta > Orthoptera > Acrididae Tropidacris dux (Drury) Photographer: Ronald F. Billings Texas Forest Service www.insectimages.org Contents How to Use This Guide Insect Models for Biomedical Research [pdf] Laboratory Care / Research | Biocontrol | Toxicology World Wide Web Resources How to Use This Guide* Insects offer an incredible advantage for many different fields of research. They are relatively easy to rear and maintain. Their short life spans also allow for reduced times to complete comprehensive experimental studies. The introductory chapter in this publication highlights some extraordinary biomedical applications. Since insects are so ubiquitous in modeling various complex systems such as nervous, reproduction, digestive, and respiratory, they are the obvious choice for alternative research strategies. -

(Hymenoptera: Encyrtidae) As a Parasitoid Of

Qeios, CC-BY 4.0 · Article, January 3, 2021 Open Peer Review on Qeios Occurrence of Ixodiphagus sp. (Hymenoptera: Encyrtidae) as a parasitoid of Carlos Henrique Marchiori1 1 Instituto Federal Goiano Funding: The author(s) received no specific funding for this work. Potential competing interests: The author(s) declared that no potential competing interests exist. Abstract The objective of this study is to describe the first occurrence of Ixodiphagus sp.(Hymenoptera: Encyrtidae) sp. parasitizing Rhipicephalus microplus (Canestrini 1888) (Acari: Ixodidae) in Goiás, Brazil. Engorged females of R. microplus collected from naturally infested cattle will be taken to the laboratory. After their death, they will be dissected to check for the presence of parasitoids. From November 2013 to October 2014, 151 engorged females belonging to the species R. microplus were collected, from which a specimen of the species Ixodiphagus sp. The percentage of parasitism was 0.6%. Key words: Ticks, Biocontrol, Natural enemy, cattle, First occurrence. Introduction Ticks are obligated hematophagous ectoparasites that feed on a wide variety of mammals, including humans and cattle. Rhipicephalus microplus (Canestrini 1888) (Acari: Ixodidae) is a cattle one-host-tick, with a tropical and subtropical cosmopolitan distribution. The R. microplus tick is responsible for considerable economic losses in Brazil, causing leather damage, weight loss and reduced milk production in cattle and results in the transmission of pathogens. Currently, the main method for controlling this tick is using acaricides, but their indiscriminate use is one of the major causes of resistance dissemination (Almazán et al. 2010, Labruna et al. 2000, 2001, Hila et al. 2016). Hymenopteran parasitoids have been shown to be of potential value in tick biocontrol (Alberto et al. -

Insects and Africa's Health 40 Years of Icipe

insects and africa’s health 40 years of icipe icipe – African Insect Science for Food and Health P.O. Box 30772-00100 Nairobi, Kenya Phone: +254 (20) 8632000 Fax: +254 (20) 8632001/2 [email protected] www.icipe.org insects and africa’s health: 40 years of icipe Contents © 2011 International Centre of Insect Physiology iii Foreword and Ecology (icipe). All rights reserved. ISBN 92 9064 222 X 1 History of icipe Published by icipe Science Press 3 Evicting Africa’s unwanted tenants P.O. Box 72913-00200 Nairobi, Kenya Tel: +254 (20) 8632000 8 Unsticking the tick Fax: +254 (20) 8632001/2 [email protected] 12 Understanding the language of locusts Article compilation: Liz Ng’ang’a and Christian Borgemeister 16 Saving the cabbage Editorial assistance: Dolorosa Osogo DTP, layout and cover design: Irene Ogendo 21 Battling a tiny but tenacious enemy Additional support: Annah Njui, Baldwyn Torto, Brigitte Nyambo, Bruno Le Ru, Caroline 27 Breaking the vicious cycle of poverty, Muya, Charles Midega, Everlyn Nguku, step by step Gerphas Okuku, James Ligare, Joash Lago, John Githure, Mary Nelima, Nguya 32 Effective partnerships in the fight Maniania, Rajinder Saini, Sunday Ekesi, against malaria Suresh Raina, Wilber Lwande and Zeyaur Khan 38 Outwitting a cryptic feeder Printed by: Kul Graphics Ltd. 42 Capacity building at icipe Cover photos courtesy of Rolf Gloor 48 Naturub® 53 Push–pull technology 60 Lethal missiles Foreword There is a popular saying that “life begins at forty”. Its inherent meaning is that, at the age of forty, an individual will have had enough experience and accomplishments to open a new, fresh and informed chapter of their life. -

Host-Seeking Activity of Ixodes Ricinus in Relation to the Epidemiology of Lyme Borreliosis in Sweden

Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Science and Technology 577 _____________________________ _____________________________ Host-seeking Activity of Ixodes ricinus in Relation to the Epidemiology of Lyme Borreliosis in Sweden BY HANS MEJLON ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS UPPSALA 2000 Dissertation for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Entomology presented at Uppsala University in 2000 Abstract Mejlon, H. 2000. Host-seeking activity of Ixodes ricinus in relation to the epidemiology of Lyme borreliosis in Sweden. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Science and Technology 577. 42 pp. Uppsala. ISBN 91-554-4842-9 This thesis examines seasonal, diel and vertical distribution patterns of activity of host- seeking Ixodes ricinus (L.) ticks at three localities in south-central Sweden. In addition, by examining the prevalence of infection in ticks with Lyme borreliosis (LB) spirochetes, Borrelia burgdorferi s.l, information for estimating relative LB risk in humans and the effect of control measures directed against this tick vector is provided. The seasonal activity pattern of I. ricinus was, in general, bimodal with peaks of activity in May-June and August-September. Tick densities were generally high at Torö and low at Kungshamn-Morga. The greatest variation in tick density occurred at the sample site level, which indicated a patchy distribution of ticks. The diel activity of adult I. ricinus sampled at Bogesund showed a distinct nocturnal activity peak while nymphal ticks exhibited no particular diel variation. At the meadow site, there was a strong negative association between activity of each tick stage and ambient air temperature, and larval ticks also showed a nocturnal activity peak.