Free Pdf Preview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Rogers Collection Inventory (Without Notes).Xlsx

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Issue No. Donor No. of copies Box # King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 13 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 14 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 12 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Alan Kupperberg and 1982 11 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Ernie Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 10 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench John Buscema, Ernie 1982 9 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 8 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 6 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Art 1988 33 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Nnicholos King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1981 5 Bill Rogers 2 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1980 3 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1980 2 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar M. Silvestri, Art Nichols 1985 29 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 30 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 31 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Vince 1986 32 Bill Rogers -

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS American Comics SETH KUSHNER Pictures

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL From the minds behind the acclaimed comics website Graphic NYC comes Leaping Tall Buildings, revealing the history of American comics through the stories of comics’ most important and influential creators—and tracing the medium’s journey all the way from its beginnings as junk culture for kids to its current status as legitimate literature and pop culture. Using interview-based essays, stunning portrait photography, and original art through various stages of development, this book delivers an in-depth, personal, behind-the-scenes account of the history of the American comic book. Subjects include: WILL EISNER (The Spirit, A Contract with God) STAN LEE (Marvel Comics) JULES FEIFFER (The Village Voice) Art SPIEGELMAN (Maus, In the Shadow of No Towers) American Comics Origins of The American Comics Origins of The JIM LEE (DC Comics Co-Publisher, Justice League) GRANT MORRISON (Supergods, All-Star Superman) NEIL GAIMAN (American Gods, Sandman) CHRIS WARE SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER (Jimmy Corrigan, Acme Novelty Library) PAUL POPE (Batman: Year 100, Battling Boy) And many more, from the earliest cartoonists pictures pictures to the latest graphic novelists! words words This PDF is NOT the entire book LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS: The Origins of American Comics Photographs by Seth Kushner Text and interviews by Christopher Irving Published by To be released: May 2012 This PDF of Leaping Tall Buildings is only a preview and an uncorrected proof . Lifting -

We Spoke Out: Comic Books and the Holocaust

W E SPOKE OUT COMIC BOOKS W E SPOKE OUT COMIC BOOKS AND THE HOLOCAUST AND NEAL ADAMS RAFAEL MEDOFF CRAIG YOE INTRODUCTION AND THE HOLOCAUST AFTERWORD BY STAN LEE NEAL ADAMS MEDOFF RAFAEL CRAIG YOE LEE STAN “RIVETING!” —Prof. Walter Reich, Former Director, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Long before the Holocaust was widely taught in schools or dramatized in films such asSchindler’s List, America’s youth was learning about the Nazi genocide from Batman, X-Men, and Captain America. Join iconic artist Neal Adams, the legend- ary Stan Lee, Holocaust scholar Dr. Rafael Medoff, and Eisner-winning comics historian Craig Yoe as they take you on an extraordinary journey in We Spoke Out: Comic Books and the Holocaust. We Spoke Out showcases classic comic book stories about the Holocaust and includes commentaries by some of their pres- tigious creators. Writers whose work is featured include Chris Claremont, Archie Goodwin, Al Feldstein, Robert Kanigher, Harvey Kurtzman, and Roy Thomas. Along with Neal Adams (who also drew the cover of this remarkable volume), artists in- clude Gene Colan, Jack Davis, Carmine Infantino, Gil Kane, Bernie Krigstein, Frank Miller, John Severin, and Wally Wood. In We Spoke Out, you’ll see how these amazing comics creators helped introduce an entire generation to a compelling and important subject—a topic as relevant today as ever. ® Visit ISBN: 978-1-63140-888-5 YoeBooks.com idwpublishing.com $49.99 US/ $65.99 CAN ® ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors are grateful to friends and colleagues who assisted with various aspects of this project: Kris Stone and Peter Stone, of Continuity Studios; Gregory Pan, of Marvel Comics; Thomas Wood, Jay Kogan, and Mandy Noack-Barr, of DC Comics; Dan Braun, of New Comic Company (Warren Publications); Corey Mifsud, Cathy Gaines-Mifsud, and Dorothy Crouch of EC Comics; Robert Carter, Jon Gotthold, Michelle Nolan, Thomas Martin, Steve Fears, Rich Arndt, Kevin Reddy, Steve Bergson, and Jeff Reid, who provided information or scans; Jon B. -

The Power of Political Cartoons in Teaching History. Occasional Paper. INSTITUTION National Council for History Education, Inc., Westlake, OH

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 425 108 SO 029 595 AUTHOR Heitzmann, William Ray TITLE The Power of Political Cartoons in Teaching History. Occasional Paper. INSTITUTION National Council for History Education, Inc., Westlake, OH. PUB DATE 1998-09-00 NOTE 10p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council for History Education, 26915 Westwood Road, Suite B-2, Westlake, OH 44145-4657; Tel: 440-835-1776. PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Cartoons; Elementary Secondary Education; Figurative Language; *History Instruction; *Humor; Illustrations; Instructional Materials; *Literary Devices; *Satire; Social Studies; United States History; Visual Aids; World History IDENTIFIERS *Political Cartoons ABSTRACT This essay focuses on the ability of the political cartoon to enhance history instruction. A trend in recent years is for social studies teachers to use these graphics to enhance instruction. Cartoons have the ability to:(1) empower teachers to demonstrate excellence during lessons; (2) prepare students for standardized tests containing cartoon questions;(3) promote critical thinking as in the Bradley Commission's suggestions for developing "History's Habits of the Mind;"(4) develop students' multiple intelligences, especially those of special needs learners; and (5) build lessons that aid students to master standards of governmental or professional curriculum organizations. The article traces the historical development of the political cartoon and provides examples of some of the earliest ones; the contemporary scene is also represented. Suggestions are given for use of research and critical thinking skills in interpreting editorial cartoons. The caricature and symbolism of political cartoons also are explored. An extensive reference section provides additional information and sources for political cartoons. -

Bruegel Notes Writing of the Novel Began October 20, 1998

Rudy Rucker, Notes for Ortelius and Bruegel, June 17, 2011 The Life of Bruegel Notes Writing of the novel began October 20, 1998. Finished first fully proofed draft on May 20, 2000 at 107,353 words. Did nothing for a year and seven months. Did revisions January 9, 2002 - March 1, 2002. Did additional revisions March 18, 2002. Latest update of the notes, September 7, 2002 64,353 Words. Table of Contents Table of Contents .................................................................................................... 1 Timeline .................................................................................................................. 9 Painting List .......................................................................................................... 10 Word Count ........................................................................................................... 12 Title ....................................................................................................................... 13 Chapter Ideas ......................................................................................................... 13 Chapter 1. Bruegel. Alps. May, 1552. Mountain Landscape. ....................... 13 Chapter 2. Bruegel. Rome. July, 1553. The Tower of Babel. ....................... 14 Chapter 3. Ortelius. Antwerp. February, 1556. The Battle Between Carnival and Lent......................................................................................................................... 14 Chapter 4. Bruegel. Antwerp. February, -

7 1Stephen A

SLIPSTREAM A DATA RICH PRODUCTION ENVIRONMENT by Alan Lasky Bachelor of Fine Arts in Film Production New York University 1985 Submitted to the Media Arts & Sciences Section, School of Architecture & Planning in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology September, 1990 c Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1990 All Rights Reserved I Signature of Author Media Arts & Sciences Section Certified by '4 A Professor Glorianna Davenport Assistant Professor of Media Technology, MIT Media Laboratory Thesis Supervisor Accepted by I~ I ~ - -- 7 1Stephen A. Benton Chairperso,'h t fCommittee on Graduate Students OCT 0 4 1990 LIBRARIES iznteh Room 14-0551 77 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02139 Ph: 617.253.2800 MITLibraries Email: [email protected] Document Services http://libraries.mit.edu/docs DISCLAIMER OF QUALITY Due to the condition of the original material, there are unavoidable flaws in this reproduction. We have made every effort possible to provide you with the best copy available. If you are dissatisfied with this product and find it unusable, please contact Document Services as soon as possible. Thank you. Best copy available. SLIPSTREAM A DATA RICH PRODUCTION ENVIRONMENT by Alan Lasky Submitted to the Media Arts & Sciences Section, School of Architecture and Planning on August 10, 1990 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science ABSTRACT Film Production has always been a complex and costly endeavour. Since the early days of cinema, methodologies for planning and tracking production information have been constantly evolving, yet no single system exists that integrates the many forms of production data. -

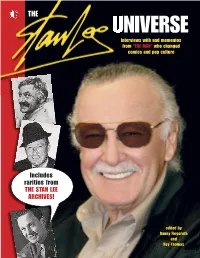

Includes Rarities from the STAN LEE ARCHIVES!

THE UNIVERSE Interviews with and mementos from “THE MAN” who changed comics and pop culture Includes rarities from THE STAN LEE ARCHIVES! edited by Danny Fingeroth and Roy Thomas CONTENTS About the material that makes up THE STAN LEE UNIVERSE Some of this book’s contents originally appeared in TwoMorrows’ Write Now! #18 and Alter Ego #74, as well as various other sources. This material has been redesigned and much of it is accompanied by different illustrations than when it first appeared. Some material is from Roy Thomas’s personal archives. Some was created especially for this book. Approximately one-third of the material in the SLU was found by Danny Fingeroth in June 2010 at the Stan Lee Collection (aka “ The Stan Lee Archives ”) of the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming in Laramie, and is material that has rarely, if ever, been seen by the general public. The transcriptions—done especially for this book—of audiotapes of 1960s radio programs featuring Stan with other notable personalities, should be of special interest to fans and scholars alike. INTRODUCTION A COMEBACK FOR COMIC BOOKS by Danny Fingeroth and Roy Thomas, editors ..................................5 1966 MidWest Magazine article by Roger Ebert ............71 CUB SCOUTS STRIP RATES EAGLE AWARD LEGEND MEETS LEGEND 1957 interview with Stan Lee and Joe Maneely, Stan interviewed in 1969 by Jud Hurd of from Editor & Publisher magazine, by James L. Collings ................7 Cartoonist PROfiles magazine ............................................................77 -

{PDF EPUB} the Comics Journal Library Vol. 1 Jack Kirby by Milo George Fiction House

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} The Comics Journal Library Vol. 1 Jack Kirby by Milo George Fiction House. Fiction House is an American publisher of pulp magazines and comic books that existed from the 1920s to the 1950s. Its comics division was best known for its pinup-style good girl art, as epitomized by the company's most popular character, Sheena, Queen of the Jungle. Contents. History. Jumbo Comics #1 (Sept 1938). Cover artist(s) unknown. Fight Stories Vol. 2, #4 (Sept 1929). Cover art by F. R. Glass. Detective Book Magazine Vol. 5, #10 (Winter 1948) Jumbo and Jack Kirby. Fiction House began in the 1920s as a pulp-magazine publisher of primarily aviation, Western and sports pulps. By the 1930s, it had expended into detective mysteries. [1] Publisher Thurman T. Scott, whose Fiction House group included the pulp-magazine imprints Glen-Kel and Real Adventures Publishing Co. , expanded into comic books in the late 1930s when that emerging medium began to seem a viable adjunct to the fading pulps. Receptive to a sales call by Eisner & Iger, one of the prominent "packagers" of that time who produced complete comic books on demand for publishers looking to enter the field, Scott released Jumbo Comics #1 (Sept. 1938). [2] Fiction House star Sheena, Queen of the Jungle appeared in that initial issue. Will Eisner and S.M. "Jerry" Iger had created the leggy, leopard- wearing jungle goddess for the British magazine Wags , [3] under the joint pseudonym "W. Morgan Thomas". [4] Fiction House's other features in that initial foray included the period adventure "Hawks of the Seas" (continuing a story from Quality Comics' Feature Funnies #12, after Eisner-Iger and Quality had had a falling out), and several now-obscure strips ("Peter Pupp"; "ZX-5 Spies in Action"; "Spencer Steel"; "Inspector Dayton"). -

Alter Ego #78 Trial Cover

TwoMorrows Publishing. Celebrating The Art & History Of Comics. SAVE 1 NOW ALL WHE5% O N YO BOOKS, MAGS RDE U & DVD s ARE ONL R 15% OFF INE! COVER PRICE EVERY DAY AT www.twomorrows.com! PLUS: New Lower Shipping Rates . s r Online! e n w o e Two Ways To Order: v i t c e • Save us processing costs by ordering ONLINE p s e r at www.twomorrows.com and you get r i e 15% OFF* the cover prices listed here, plus h t 1 exact weight-based postage (the more you 1 0 2 order, the more you save on shipping— © especially overseas customers)! & M T OR: s r e t • Order by MAIL, PHONE, FAX, or E-MAIL c a r at the full prices listed here, and add $1 per a h c l magazine or DVD and $2 per book in the US l A for Media Mail shipping. OUTSIDE THE US , PLEASE CALL, E-MAIL, OR ORDER ONLINE TO CALCULATE YOUR EXACT POSTAGE! *15% Discount does not apply to Mail Orders, Subscriptions, Bundles, Limited Editions, Digital Editions, or items purchased at conventions. We reserve the right to cancel this offer at any time—but we haven’t yet, and it’s been offered, like, forever... AL SEE PAGE 2 DIGITIITONS ED E FOR DETAILS AVAILABL 2011-2012 Catalog To get periodic e-mail updates of what’s new from TwoMorrows Publishing, sign up for our mailing list! ORDER AT: www.twomorrows.com http://groups.yahoo.com/group/twomorrows TwoMorrows Publishing • 10407 Bedfordtown Drive • Raleigh, NC 27614 • 919-449-0344 • FAX: 919-449-0327 • e-mail: [email protected] TwoMorrows Publishing is a division of TwoMorrows, Inc. -

PDF Free Rip Kirby Volume 1

Register Free To Download Files | File Name : Rip Kirby Volume 1 PDF RIP KIRBY VOLUME 1 Tapa dura 1 diciembre 2009 Author : Alex Raymond Descripcin del productoCrticas"A treasure not to be missed." --ScoopBiografa del autorAlex Raymond (1909-1956) is regarded, with Milton Caniff and Hal Foster, as one of the three giants of newspaper adventure strip artists. Raymond apprenticed with Chic Young on Blondie, and Lymon Young on Tim Tyler's Luck. The year 1934 was a major turning point in his career: he illustrated X- 9, a new detective comic strip written by Dashiell Hammett, and then created Flash Gordon and Jungle Jim. Rip Kirby, created in 1946, signaled a grand departure, both thematically and artistically, from the science fiction classic. He promulgated a new art style--one of cinematic photo-realism--that influenced such artists as Stan Drake, Leonard Starr, Al Williamson, and Neal Adams. Great art, good printing IDW produced another great book, beautifully crafted, with an interesting essay on Alex Raymond and Rip Kirby. Every effort was made to find the best sources for the dailies: it's a pity that they are not - apparently - syndicated proofs; very few are from original art (the first week and some others); the bulk is made of pretty good reproductions, some from second generation sources; some are not so good... I wonder: where are the KFS proofs?Forgive my English Five Stars Presenting the first volume of Alex Raymond's modernist classic Rip Kirby from its start in 1946. Created by Alex Raymond when he was deactivated from the Marines after World War II, Rip Kirby was a fresh approach to the genre, a departure from the prevailing hard-boiled style of detective fiction. -

An Exploration of Comics and Architecture in Post-War Germany and the United States

An Exploration of Comics and Architecture in Post-War Germany and the United States A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Ryan G. O’Neill IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Dr. Rembert Hueser, Adviser October 2016 © Ryan Gene O’Neill 2016 Table of Contents List of Figures……………………………………………………………………………………...……….i Prologue……………………………………………………………………………………….....…1 Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………...8 Chapter 1: The Comic Laboratory…………………………………………………...…………………………………….31 Chapter 2: Comics and Visible Time…………………………………………………………………………...…………………..52 Chapter 3: Comic Cities and Comic Empires………………………………...……………………………...……..…………………….80 Chapter 4: In the Shadow of No Archive…………………………………………………………………………..…….…………114 Epilogue: The Painting that Ate Paris………………………………………………………………………………...…………….139 Works Cited…..……………………………………………………………………………..……152 i Figures Prologue Figure 1: Kaczynski, Tom (w)(a). “Skyway Sleepless.” Twin Cities Noir: The Expanded Edition. Ed. Julie Schaper, Steven Horwitz. New York: Akashic Books, 2013. Print. Figure 2: Kaczynski, Tom (w)(a). “Skyway Sleepless.” Twin Cities Noir: The Expanded Edition. Ed. Julie Schaper, Steven Horwitz. New York: Akashic Books, 2013. Print. Figure 3: Image of Vitra Feuerwehrhaus Uncredited. https://www.vitra.com/de-de/campus/architecture/architecture-fire-station Figure 4: Kaczynski, Tom (w)(a). “Skyway Sleepless.” Twin Cities Noir: The Expanded Edition. Ed. Julie Schaper, Steven Horwitz. New York: Akashic Books, 2013. Print. Introduction Figure 1: Goscinny, René (w), Alberto Uderzo (i). Die Trabantenstadt. trans. Gudrun Penndorf. Stuttgart: Ehapa Verlag GmbH, 1974. Pp.28-29. Print. Figure 2: Forum at Pompeii, Vitruvius Vitrubius. The Ten Books on Architecture. trans. Morris Hicky Morgan, Ph.D., LL.D. Illustrations under the direction of Herbert Langford Warren, A.M. pp. 132. Print. Figure 3: Töpffer, Rodolphe. -

The Illustration Game: Quotes & Notes

Rhode Island School of Design DigitalCommons@RISD Faculty & Librarian Work RISD Faculty & Librarians 1-1-2019 The Illustration Game: Quotes & Notes Jaleen Grove Rhode Island School of Design, [email protected] Illustration Department Rhode Island School of Design, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.risd.edu/faculty_work Part of the Illustration Commons Recommended Citation Grove, Jaleen and Department, Illustration, "The Illustration Game: Quotes & Notes" (2019). Faculty & Librarian Work. 4. https://digitalcommons.risd.edu/faculty_work/4 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the RISD Faculty & Librarians at DigitalCommons@RISD. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty & Librarian Work by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@RISD. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Illustration Game: Quotes and Notes Jaleen Grove The Illustration Game, published in Communication Arts magazine, is an artwork that critically evaluates and satirizes the illustration industry 1959-2019. It conceives of the time period in the form of a board game in which players roll a die to advance along a path, accumulating points or losing them according to typical events of each decade. The path winds through a forest of quotations that were said in print at the time or shortly after by leading illustrators and critics. For the quotations to read properly and succinctly, wording was very slightly modified in some cases. The sources and the quotes without modification are given here for those who wish to see context and origin. This document only discusses the quotations that appear in the black background.