Enhancing Stabilization and Reconstruction Operations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AUGUST 2021 May 2019: Admiral Sir Timothy P. Fraser

ADMIRALS: AUGUST 2021 May 2019: Admiral Sir Timothy P. Fraser: Vice-Chief of the Defence Staff, May 2019 June 2019: Admiral Sir Antony D. Radakin: First Sea Lord and Chief of the Naval Staff, June 2019 (11/1965; 55) VICE-ADMIRALS: AUGUST 2021 February 2016: Vice-Admiral Sir Benjamin J. Key: Chief of Joint Operations, April 2019 (11/1965; 55) July 2018: Vice-Admiral Paul M. Bennett: to retire (8/1964; 57) March 2019: Vice-Admiral Jeremy P. Kyd: Fleet Commander, March 2019 (1967; 53) April 2019: Vice-Admiral Nicholas W. Hine: Second Sea Lord and Deputy Chief of the Naval Staff, April 2019 (2/1966; 55) Vice-Admiral Christopher R.S. Gardner: Chief of Materiel (Ships), April 2019 (1962; 58) May 2019: Vice-Admiral Keith E. Blount: Commander, Maritime Command, N.A.T.O., May 2019 (6/1966; 55) September 2020: Vice-Admiral Richard C. Thompson: Director-General, Air, Defence Equipment and Support, September 2020 July 2021: Vice-Admiral Guy A. Robinson: Chief of Staff, Supreme Allied Command, Transformation, July 2021 REAR ADMIRALS: AUGUST 2021 July 2016: (Eng.)Rear-Admiral Timothy C. Hodgson: Director, Nuclear Technology, July 2021 (55) October 2017: Rear-Admiral Paul V. Halton: Director, Submarine Readiness, Submarine Delivery Agency, January 2020 (53) April 2018: Rear-Admiral James D. Morley: Deputy Commander, Naval Striking and Support Forces, NATO, April 2021 (1969; 51) July 2018: (Eng.) Rear-Admiral Keith A. Beckett: Director, Submarines Support and Chief, Strategic Systems Executive, Submarine Delivery Agency, 2018 (Eng.) Rear-Admiral Malcolm J. Toy: Director of Operations and Assurance and Chief Operating Officer, Defence Safety Authority, and Director (Technical), Military Aviation Authority, July 2018 (12/1964; 56) November 2018: (Logs.) Rear-Admiral Andrew M. -

William D. Sullivan, Navy Vice Admiral Bill Sullivan Graduated from Florida

William D. Sullivan, Navy Vice Admiral Bill Sullivan graduated from Florida State University in June 1972. He received his Navy commission in September 1972 following graduation from Officer Candidate School in Newport, Rhode Island. During his 37 years of active duty, Vice Admiral Sullivan served in a variety of sea-going assignments including cruiser, destroyer and frigate class surface ships and aircraft carrier strike group staffs. He commanded the guided missile destroyer USS SAMPSON (DDG 10)during Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm, deploying to the Red Sea while enforcing United Nations sanctions on Iraq. From 1997 to 1999 he commanded the Aegis guided missile cruiser USS COWPENS (CG 63), deploying to the Persian Gulf and executing Tomahawk strike operations against Al Qaeda in Afghanistan. Vice Admiral Sullivan has served in a variety of staff positions. Joint assignments include Director for Pacific Operations on the Joint Staff (J-3), Director for Strategic Plans and Policy (J- 5) at U.S. Pacific Command and Vice Director, Strategic Plans and Policy (J-5) on the Joint Staff. From 1999 to 2001 he served as Commander, U.S. Naval Forces, Korea. Prior to his retirement from active duty, Vice Admiral Sullivan served as the U.S. Representative to the NATO Military Committee, NATO Headquarters, Brussels, Belgium. Vice Admiral Sullivan earned a Masters Degree in National Security Studies at Georgetown University in 1990 and a Masters Degree in National Security Affairs at the National War College in 1994. Vice Admiral Sullivan is a member of the Veterans Advisory Board for the Florida State University Veterans Legacy Complex which will house student-veteran programs, the Army and Air Force ROTC offices, and the archives and offices of the Institute on World War II and the Human Experience. -

Abbreviations and Acronyms

PART II] THE GAZETTE OF PAKISTAN, EXTRA., MARCH 5, 2019 1 ISLAMABAD, TUESDAY, MARCH 5, 2019 PART II Statutory Notifications, (S.R.O.) GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN MINISTRY OF DEFENCE (Navy Branch) NOTIFICATIONS Rawalpindi, the 25th February, 2019 S.R.O. 283(I)/2019.—The following confirmation is made in the rank of Lieut under N.I. 20/71: Pakistan Navy Ag Lt to be Lt Date of Seniority Date of Grant of Gained during S. No Rank/Name/P No Confirmation SSC as Ag Training as Lt Lt (M-D) Ag Lt (SSC)(WE) 06-01-14 with 1. Muhammad Fawad Hussain PN 06-01-14 +01-25 seniority from (P No 9094) 11-11-13 [Case No.CW/0206/70/PC/NHQ/ dated.] (1) Price: Rs. 20.00 [340(2019)/Ex. Gaz.] 2 THE GAZETTE OF PAKISTAN, EXTRA., MARCH 5, 2019 [PART II S.R.O. 284(I)/2019.—Following officers are granted local rank of Commander w.e.f the dates mentioned against their names under NR-0634: S. No. Rank/Name/P No Date of Grant of Local Rank of Cdr OPERATIONS BRANCH 1. Lt Cdr (Ops) Muhammad Saleem PN 06-05-18 (P No 5111) 2. Lt Cdr (Ops) Wasim Zafar PN 01-07-18 (P No 6110) 3. Lt Cdr (Ops) Mubashir Nazir Farooq PN 01-07-18 (P No 6204) 4. Lt Cdr (Ops) Mohammad Ayaz PN 01-07-18 (P No 6217) 5. Lt Cdr (Ops) Tahir Majeed Asim TI(M) PN 01-07-18 (P No 6229) 6. Lt Cdr (Ops) Muhammad Farman PN 01-07-18 (P No 6209) 7. -

PRISM Vol 3, No 1

PRISM❖ Vol. 3, no. 1 12/2011 PRISM Vol. 3, no. 1 3, no. Vol. ❖ 12/2011 www.ndu.edu A JOURNAL OF THE CENTER FOR COMPLEX OPERATIONS PRISM ABOUT CENTER FOR COMPLEX OPERATIONS (CCO) CCO WAS ESTABLISHED TO: PRISM is published by the National Defense University Press for the Center for ❖❖ Serve as an information clearinghouse and knowledge Enhancing the U.S. Government’s Ability to manager for complex operations training and education, PUBLISHER Complex Operations. PRISM is a security studies journal chartered to inform members of U.S. Federal agencies, allies, and other partners on complex and Prepare for Complex Operations acting as a central repository for information on areas Dr. Hans Binnendijk integrated national security operations; reconstruction and nation-building; such as training and curricula, training and education pro- CCO, a center within the Institute for National Strategic relevant policy and strategy; lessons learned; and developments in training and vider institutions, complex operations events, and subject EDITOR AND RESEARCH DIRECTOR Studies at National Defense University, links U.S. education to transform America’s security and development apparatus to meet matter experts Government education and training institutions, including Michael Miklaucic tomorrow’s challenges better while promoting freedom today. related centers of excellence, lessons learned programs, ❖❖ Develop a complex operations training and education com- and academia, to foster unity of effort in reconstruction munity of practice to catalyze innovation and development DEVELOPMENTAL EDITOR and stability operations, counterinsurgency, and irregular of new knowledge, connect members for networking, share Melanne A. Civic, Esq. COMMUNICATIONS warfare—collectively called “complex operations.” existing knowledge, and cultivate foundations of trust and The Department of Defense, with support from the habits of collaboration across the community Constructive comments and contributions are important to us. -

High Hopes and Missed Opportunities in Iraq Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE UNRAVELLING: HIGH HOPES AND MISSED OPPORTUNITIES IN IRAQ PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Emma Sky | 400 pages | 05 May 2016 | ATLANTIC BOOKS | 9781782392606 | English | London, United Kingdom The Unraveling: High Hopes and Missed Opportunities in Iraq by Emma Sky Iraq was in the midst of civil war. But we were not allowed to acknowledge it because it was not what Washington wanted to hear. Through the next three long years the situation in Iraq went from horrible to tolerable to seeming really pretty good. Then it fell apart. The United States military surge won back a semblance of peace and stability in the city of Baghdad while a radical rethinking of American policy toward Sunni tribes that had been allied with the insurgency opened the door for them to change sides. Once they were on the American payroll, they played a vital role in crushing what was called, at the time, Al Qaeda in Iraq. David Petraeus, whose name had become synonymous with sophisticated counterinsurgency. Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki and his coalition were defeated in parliamentary elections in by a more centrist, nonsectarian candidate and an old favorite of the Central Intelligence Agency , Ayad Allawi. But Maliki, by playing his many sectarian cards, managed to hold on to power, and in the process reignited the hideous intercommunal violence most Iraqis hoped was behind them. Hill, a career diplomat with a long track record in Asia but no feel for the Middle East. And it appears the feeling was mutual. The enormous importance of long-term relationships in Middle East politics seems to have escaped Hill, and those relationships were exactly what Sky was all about. -

Developing Senior Navy Leaders: Requirements for Flag Officer

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available CHILD POLICY from www.rand.org as a public service of CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION the RAND Corporation. ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit NATIONAL SECURITY research organization providing POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY objective analysis and effective SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY solutions that address the challenges SUBSTANCE ABUSE facing the public and private sectors TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY around the world. TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND National Defense Research Institute View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Developing Senior Navy Leaders Requirements for Flag Officer Expertise Today and in the Future Lawrence M. -

Soldiering and the Making of Finnish Manhood

Soldiering and the Making of Finnish Manhood Conscription and Masculinity in Interwar Finland, 1918–1939 ANDERS AHLBÄCK Doctoral Thesis in General History ÅBO AKADEMI UNIVERSITY 2010 © Anders Ahlbäck Author’s address: History Dept. of Åbo Akademi University Fabriksgatan 2 FIN-20500 Åbo Finland e-mail: [email protected] ISBN 978-952-12-2508-6 (paperback) ISBN 978-952-12-2509-3 (pdf) Printed by Uniprint, Turku Table of Contents Acknowledgements v 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Images and experiences of conscripted soldiering 1 1.2 Topics in earlier research: The militarisation of modern masculinity 8 1.3 Theory and method: Conscription as a contested arena of masculinity 26 1.4 Demarcation: Soldiering and citizenship as homosocial enactments 39 2 The politics of conscription 48 2.1 Military debate on the verge of a revolution 52 2.2 The Civil War and the creation of the “White Army” 62 2.3 The militiaman challenging the cadre army soldier 72 2.4 From public indignation to closing ranks around the army 87 2.5 Conclusion: Reluctant militarisation 96 3 War heroes as war teachers 100 3.1 The narrative construction of the Jägers as war heroes 102 3.2 Absent women and distant domesticity 116 3.3 Heroic officers and their counter-images 118 3.4 Forgetfulness in the hero myth 124 3.5 The Jäger officers as military educators 127 3.6 Conclusion: The uses of war heroes 139 4 Educating the citizen-soldier 146 4.1 Civic education and the Suomen Sotilas magazine 147 4.2 The man-soldier-citizen amalgamation 154 4.3 History, forefathers and the spirit of sacrifice -

Rank in the Navy

RANK IN THE NAYY. SPEECH OF HON. AARON F. STEVENS, OF NEW HAMPSHIRE, DELIVERED IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, January 23, 1871. WASHINGTON, D. C. : JUDD & DETWEILER, PRINTERS AND PUBLISHERS 1871, SPEECH The House having under consideration the bill (H. R. No. 1832) toregulaterank in the Navy of the United States, and for other purposes— Mr. STEVENS said: Mr. Speaker : As the gentleman from Pennsylvania does not in- dicate the amount of time which he wishes to occupy, I will proceed to state generally the provisions of the bill, and to some extent its history, after which I will cheerfully yield to the gentleman from Pennsylvania. I am quite sure that the gentlemen of this House, whose attention I shall have the honor-to secure, will not confess themselves strangers to the question raised by the provisions of this bill. Nor will they, I think, treat it as a trivial or unimportant question, connected as it is with one of the principal branches of the public service. I do not seek to disguise the fact that within the past two years the regu- lation of rank in the Navy has become a question of more public importance than has ever been conceded to it in former times outside of those immediately interested in its settlement. It is but truth to say that no question of military organization and detail has ever, except in time of war, excited so much interest as that to which I now desire to call the attention of the House, and which this bill seeks to regulate and fix upon a just and permanent basis. -

Building a U.S. Coast Guard for the 21St Century

WWW.AMERICANPROGRESS.ORG June 2010 Building a U.S. Coast Guard for the for Guard Coast Building a U.S. By Lawrence J. Korb, Sean Conley Duggan, and Laura Korb, J. By Lawrence 21st Century AP PHOTO/U.S. COAST GuaRD, PETTY OFFICER 2ND CLASS ETTA SMITH Building a U.S. Coast Guard for the 21st Century By Lawrence J. Korb, Sean Duggan, and Laura Conley June 2010 Contents 1 Introduction and summary 7 Fiscal constraints 17 Personnel challenges 23 Defense readiness challenges 29 Coast Guard recapitalization 39 Coast Guard organizational restructuring 44 Preparing for climate change 50 Conclusion 51 Endnotes 54 About the authors and acknowledgements Introduction and summary Our nation today demands more from the U.S. Coast Guard, the nation’s oldest maritime force, than at any time in the service’s history. Coast Guard personnel and assets are conducting counterpiracy missions in the Gulf of Aden, protecting Iraqi petroleum pipelines and shipping lanes in the Persian Gulf, and shouldering the load in the government’s response efforts to the massive Deepwater Horizon oil spill off the coast of Louisiana, the largest oil spill in the nation’s history. The Coast Guard remains heavily engaged in all of these theatres in addition to its traditional and better-known search and rescue, drug interdiction, and port security missions. The accelerated pace and scope of these domestic and international missions is the new norm for the Coast Guard. But if the Obama administration and Congress expect the Coast Guard to maintain its current level of operations effectively, they must begin providing the service with the commensurate leadership and resources necessary to transform and modernize the service. -

US Military Ranks and Units

US Military Ranks and Units Modern US Military Ranks The table shows current ranks in the US military service branches, but they can serve as a fair guide throughout the twentieth century. Ranks in foreign military services may vary significantly, even when the same names are used. Many European countries use the rank Field Marshal, for example, which is not used in the United States. Pay Army Air Force Marines Navy and Coast Guard Scale Commissioned Officers General of the ** General of the Air Force Fleet Admiral Army Chief of Naval Operations Army Chief of Commandant of the Air Force Chief of Staff Staff Marine Corps O-10 Commandant of the Coast General Guard General General Admiral O-9 Lieutenant General Lieutenant General Lieutenant General Vice Admiral Rear Admiral O-8 Major General Major General Major General (Upper Half) Rear Admiral O-7 Brigadier General Brigadier General Brigadier General (Commodore) O-6 Colonel Colonel Colonel Captain O-5 Lieutenant Colonel Lieutenant Colonel Lieutenant Colonel Commander O-4 Major Major Major Lieutenant Commander O-3 Captain Captain Captain Lieutenant O-2 1st Lieutenant 1st Lieutenant 1st Lieutenant Lieutenant, Junior Grade O-1 2nd Lieutenant 2nd Lieutenant 2nd Lieutenant Ensign Warrant Officers Master Warrant W-5 Chief Warrant Officer 5 Master Warrant Officer Officer 5 W-4 Warrant Officer 4 Chief Warrant Officer 4 Warrant Officer 4 W-3 Warrant Officer 3 Chief Warrant Officer 3 Warrant Officer 3 W-2 Warrant Officer 2 Chief Warrant Officer 2 Warrant Officer 2 W-1 Warrant Officer 1 Warrant Officer Warrant Officer 1 Blank indicates there is no rank at that pay grade. -

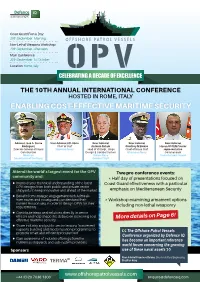

Enabling Cost-Effective Maritime Security

Coast Guard Focus Day: 29th September - Morning Non-Lethal Weapons Workshop: 29th September - Afternoon Main Conference: 30th September -1st October Location: Rome, Italy CELEBRATING A DECADE OF EXCELLENCE THE 10TH Annual International CONFERENCE HOSTED IN ROME, ITALY ENABLING COST-EFFECTIVE MARITIME SECURITY Admiral José A. Sierra Vice Admiral UO Jibrin Rear Admiral Rear Admiral Rear Admiral Rodríguez Chief of Staff Antonio Natale Geoffrey M Biekro Hasan ÜSTEM/Senior Director General of Naval Nigerian Navy Head of VII Dept., Ships Chief of Naval Staff representative Construction Design & Combat System Ghanaian Navy Commandant Mexican Italian Navy Turkish Coast Guard Secretariat of the Navy General Staff Attend the world’s largest event for the OPV Two pre-conference events: community and: * Half day of presentations focused on • Improve your technical understanding of the latest Coast Guard effectiveness with a particular OPV designs from both public and private sector shipyards to keep innovative and ahead of the market emphasis on Mediterranean Security • Benefit from strategic engagement with Admirals from navies and coastguards; understand their * Workshop examining armament options current mission sets in order to design OPVs for their requirements including non-lethal weaponry • Contribute ideas and solutions directly to senior officers and help shape the debate on delivering cost- More details on Page 6! effective maritime security. • Share industry and public sector lessons from recent capacity building and modernisation programmes -

Emma Sky Written by E-International Relations

Interview - Emma Sky Written by E-International Relations This PDF is auto-generated for reference only. As such, it may contain some conversion errors and/or missing information. For all formal use please refer to the official version on the website, as linked below. Interview - Emma Sky https://www.e-ir.info/2018/06/26/interview-emma-sky/ E-INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS, JUN 26 2018 Emma Sky is Director of Yale World Fellows and a Senior Fellow at Yale University’s Jackson Institute, where she teaches Middle East politics. She is the author of The Unraveling: High Hopes and Missed Opportunities in Iraq , which was one of the New York Times 100 notable books of 2015, and Shortlisted for the 2016 Council on Foreign Relations Arthur Ross Prize, the 2016 Orwell Prize and the 2015 Samuel Johnson Prize for Nonfiction. Emma served as advisor to the Commanding General of US Forces in Iraq from 2007-2010; as advisor to the Commander of NATO’s International Security Assistance Force in Afghanistan in 2006; as advisor to the US Security Co-ordinator for the Middle East Peace Process in 2005; and as Governorate Co-ordinator of Kirkuk for the Coalition Provisional Authority, 2003-2004. Prior to that, Emma worked in the Palestinian territories for a decade, managing projects to develop Palestinian institutions; and to promote co-existence between Israelis and Palestinians. Where do you see the most exciting research/debates happening in your field? We are transitioning from a unipolar system to a multipolar one, with the Middle East one of multiple and competing spheres of influence.