A Census of Orphans and Vulnerable Children in Two Zimbabwean Districts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bulawayo City Mpilo Central Hospital

Province District Name of Site Bulawayo Bulawayo City E. F. Watson Clinic Bulawayo Bulawayo City Mpilo Central Hospital Bulawayo Bulawayo City Nkulumane Clinic Bulawayo Bulawayo City United Bulawayo Hospital Manicaland Buhera Birchenough Bridge Hospital Manicaland Buhera Murambinda Mission Hospital Manicaland Chipinge Chipinge District Hospital Manicaland Makoni Rusape District Hospital Manicaland Mutare Mutare Provincial Hospital Manicaland Mutasa Bonda Mission Hospital Manicaland Mutasa Hauna District Hospital Harare Chitungwiza Chitungwiza Central Hospital Harare Chitungwiza CITIMED Clinic Masvingo Chiredzi Chikombedzi Mission Hospital Masvingo Chiredzi Chiredzi District Hospital Masvingo Chivi Chivi District Hospital Masvingo Gutu Chimombe Rural Hospital Masvingo Gutu Chinyika Rural Hospital Masvingo Gutu Chitando Rural Health Centre Masvingo Gutu Gutu Mission Hospital Masvingo Gutu Gutu Rural Hospital Masvingo Gutu Mukaro Mission Hospital Masvingo Masvingo Masvingo Provincial Hospital Masvingo Masvingo Morgenster Mission Hospital Masvingo Mwenezi Matibi Mission Hospital Masvingo Mwenezi Neshuro District Hospital Masvingo Zaka Musiso Mission Hospital Masvingo Zaka Ndanga District Hospital Matabeleland South Beitbridge Beitbridge District Hospital Matabeleland South Gwanda Gwanda Provincial Hospital Matabeleland South Insiza Filabusi District Hospital Matabeleland South Mangwe Plumtree District Hospital Matabeleland South Mangwe St Annes Mission Hospital (Brunapeg) Matabeleland South Matobo Maphisa District Hospital Matabeleland South Umzingwane Esigodini District Hospital Midlands Gokwe South Gokwe South District Hospital Midlands Gweru Gweru Provincial Hospital Midlands Kwekwe Kwekwe General Hospital Midlands Kwekwe Silobela District Hospital Midlands Mberengwa Mberengwa District Hospital . -

Zimbabwean Government Gazette, 8Th February, 1985 103

GOVERNMENT?‘GAZETTE Published by Autry £ x | Vol. LX, No, 8 f 8th FEBRUARY,1985 Price 30c 3 General Notice 92 of 1985, The service to operate as follows— Route 1: , 262] > * ROAD MOTOR TRANSPORTATION ACT [CHAPTER (a) depart Bulawayo Monday 9 am., arrive Beitbridge 3.15 p.m.; Applications in Connexion with Road Service Permits (b) depart Bulawayo. Friday 5 pm., arrive Beitbridge as 11.15 p.m. _ IN terms of subsection(4) of section 7 of the- Road Moter ‘(c) depart BulawayoB Saturday 10 am., arrive Beitbridge Transportation Act [Chapter 262], notice is hereby given that 13 ‘p. the applications detailed in the Schedule, for the issue or | (d) depart eitbridge Tuesday 8.40 a.m., astive Bulawayo amendment of road service its, have been received for the 3.30 p. consideration of the Control}ér of Road Motor Transportation. (e) depart Beitbridge Saturday 3.40 am., arrive Bulawayo Any personwishing to Object to any such application must - a.m} ‘lodge with the Controlle? of Road Motor Transportation, (f) depart’ Beitbridge Sunday 9.40 am., arrive Bulawayo P.O. Box 8332, Causeway— 4.30 p.m, ~ . : eg. (a) a notice; in writing, of his intention fo object, so as to - Route 2: No change. _* teach the Controller'ss office not later than the Ist March, Cc. R. BHana. ’ 1985; 0/284/84. Permit: 23891."Motor-omnibus. Passenger-capacity: (b) his objection and the groiinds therefor, on form R.M.T, 24, tozether with two copies thereof, so as to reach the Route: Bulawayo - Zyishavane - _Mashava - Masvingo - Controller’s office not later than the 22nd March, 1985. -

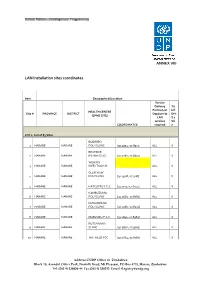

LAN Installation Sites Coordinates

ANNEX VIII LAN Installation sites coordinates Item Geographical/Location Service Delivery Tic Points (List k if HEALTH CENTRE Site # PROVINCE DISTRICT Dept/umits DHI (EPMS SITE) LAN S 2 services Sit COORDINATES required e LOT 1: List of 83 Sites BUDIRIRO 1 HARARE HARARE POLYCLINIC [30.9354,-17.8912] ALL X BEATRICE 2 HARARE HARARE RD.INFECTIO [31.0282,-17.8601] ALL X WILKINS 3 HARARE HARARE INFECTIOUS H ALL X GLEN VIEW 4 HARARE HARARE POLYCLINIC [30.9508,-17.908] ALL X 5 HARARE HARARE HATCLIFFE P.C.C. [31.1075,-17.6974] ALL X KAMBUZUMA 6 HARARE HARARE POLYCLINIC [30.9683,-17.8581] ALL X KUWADZANA 7 HARARE HARARE POLYCLINIC [30.9285,-17.8323] ALL X 8 HARARE HARARE MABVUKU P.C.C. [31.1841,-17.8389] ALL X RUTSANANA 9 HARARE HARARE CLINIC [30.9861,-17.9065] ALL X 10 HARARE HARARE HATFIELD PCC [31.0864,-17.8787] ALL X Address UNDP Office in Zimbabwe Block 10, Arundel Office Park, Norfolk Road, Mt Pleasant, PO Box 4775, Harare, Zimbabwe Tel: (263 4) 338836-44 Fax:(263 4) 338292 Email: [email protected] NEWLANDS 11 HARARE HARARE CLINIC ALL X SEKE SOUTH 12 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA CLINIC [31.0763,-18.0314] ALL X SEKE NORTH 13 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA CLINIC [31.0943,-18.0152] ALL X 14 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA ST.MARYS CLINIC [31.0427,-17.9947] ALL X 15 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA ZENGEZA CLINIC [31.0582,-18.0066] ALL X CHITUNGWIZA CENTRAL 16 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA HOSPITAL [31.0628,-18.0176] ALL X HARARE CENTRAL 17 HARARE HARARE HOSPITAL [31.0128,-17.8609] ALL X PARIRENYATWA CENTRAL 18 HARARE HARARE HOSPITAL [30.0433,-17.8122] ALL X MURAMBINDA [31.65555953980,- 19 MANICALAND -

Zimbabwe-HIV-Estimates Report 2018

ZIMBABWE NATIONAL AND SUB-NATIONAL HIV ESTIMATES REPORT 2017 AIDS & TB PROGRAMME MINISTRY OF HEALTH AND CHILD CARE July 2018 Foreword The Ministry of Health and Child Care (MOHCC) in collaboration with National AIDS Council (NAC) and support from partners, produced the Zimbabwe 2017 National, Provincial and District HIV and AIDS Estimates. The UNAIDS, Avenir Health and NAC continued to provide technical assistance and training in order to build national capacity to produce sub-national estimates in order to track the epidemic. The 2017 Estimates report gives estimates for the impact of the programme. It provide an update of the HIV and AIDS estimates and projections, which include HIV prevalence and incidence, programme coverages, AIDS-related deaths and orphans, pregnant women in need of PMTCT services in the country based on the Spectrum Model version 5.63. The 2017 Estimates report will assist the country to monitor progress towards the fast track targets by outlining programme coverage and possible gaps. This report will assist programme managers in accounting for efforts in the national response and policy makers in planning and resource mobilization. Brigadier General (Dr.) G. Gwinji Permanent Secretary for Health and Child Care Page | i Acknowledgements The Ministry of Health and Child Care (MOHCC) would want to acknowledge effort from all individuals and organizations that contributed to the production of these estimates and projections. We are particularly grateful to the National AIDS Council (NAC) for funding the national and sub-national capacity building and report writing workshop. We are also grateful to the National HIV and AIDS Estimates Working Group for working tirelessly to produce this report. -

TREATMENT SITES Southern Africa HIV and AIDS Information LISTED by PROVINCE and AREA Dissemination Service

ARV TREATMENT SITES Southern Africa HIV and AIDS Information LISTED BY PROVINCE AND AREA Dissemination Service MASVINGO · Bulilima: Plumtree District hospital: · Bikita: Silveira Mission Hospital: Tel: (038)324 Tel. (019) 2291; 2661-3 · Chiredzi: Hippo Valley Estates Clinic: · Gwanda: Gwanda OI Clinic: Tel: (084)22661-3: Tel: (031)2264 - Mangwe: St. Annes Brunapeg: · Chiredzi: Colin Saunders Hosp. Tel: (082) 361/466 AN HIV/AIDS Tel: (033)6387:6255 · Kezi-Matobo: Tshelanyemba Mission Hosp: · Chiredzi: Chiredzi District Hosp.: Tel: (033) Tel: (082) 254 · Gutu: Gutu Mission Hosp: · Maphisa District Hosp: Tel. (082) 244 Tel: (030)2323:2313:2631:3229 · Masvingo: Morgenster Mission Hosp: MIDLANDS Tel: (039)262123 · Chivhu General Hosp: Tel: (056):2644:2351 TREATMENT - Masvingo Provincial Hosp: · Chirumhanzu: Muvonde Hosp: Tel: (032)346 Tel: (039)263358/9; 263360 · Mvuma: St Theresas Mission Hosp: - Masvingo: Mukurira Memorial Private Hospital: Tel: (0308)208/373 Tel. (039) 264919 · Gweru: Gweru Provincial Hospital: ROADMAP FOR · Mwenezi: Matibi Mission Hospital: Tel. (0517) 323 Tel: (054) 221301:221108 · Zaka: Musiso Mission Hosp: · Gweru: Gweru City Hospital: Tel: (054) Tel: (034)2286:2322:2327/8 221301:221108 - Gweru: Mkoba 1 Polyclinic, Tel. MATEBELELAND NORTH - Gweru: Lower Gweru Rural Health Clinic: · Hwange: St Patricks Mission Hosp: Tel: (054) 227023 Tel: (081)34316-7 · Kwekwe: Kwekwe General Hospital: ZIMBABWE · Lupane: St Lukes Mission Hosp: Tel: (055)22333/7:24828/31 Tel: (0898)362:549:349 · Mberengwa: Mnene Mission Hospital: · Tsholotsho: Tsholotsho District Hosp: Tel. (0518) 352/3 Tel: (0878) 397/216/299 A guide for accessing anti- PRIVATE DOCTORS retroviral treatment in MATEBELELAND SOUTH For a list of private doctors who have special Zimbabwe: what it is, where · Beitbridge: Beitbridge District Hosp: training in ARV treatment and counselling, ask Tel.(086) 22496-8 your own doctor or contact SAfAIDS. -

Zimbabweans Who Move:Perspectives on International Migration in Zimbabwe

THE SOUTHERN AFRICAN MIGRATION PROJECT ZIMBABWEANS WHO MOVE: PERSPECTIVES ON INTERNATIONAL MIGRATION IN ZIMBABWE MIGRATION POLICY SERIES NO. 25 ZIMBABWEANS WHO MOVE: PERSPECTIVES ON INTERNATIONAL MIGRATION IN ZIMBABWE DANIEL TEVERA AND LOVEMORE ZINYAMA SERIES EDITOR: PROF. JONATHAN CRUSH SOUTHERN AFRICAN MIGRATION PROJECT Published by Idasa, 6 Spin Street, Church Square, Cape Town, 8001, and Southern African Research Centre, Queen’s University, Canada. Copyright Southern African Migration Project (SAMP) 2002 ISBN 1-919798-40-4 First published 2002 Design by Bronwen Dachs Müller Typeset in Goudy All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission from SAMP. Bound and printed by Creda Communications, Cape Town CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION:ZIMBABWEANS WHO MOVE 1 CHAPTER ONE:INTERNATIONAL MIGRATION AND ZIMBABWE:AN OVERVIEW 1.1 INTRODUCTION 7 1.2 LEGAL IMMIGRATION TO ZIMBABWE 8 1.3 VISITORS TO ZIMBABWE 14 1.4 ZIMBABWEANS VISITING ABROAD 17 1.5 UNAUTHORIZED MIGRATION 19 1.6 GOVERNMENT POLICIES TOWARDS MIGRATION 22 1.7 CONCLUSION 25 CHAPTER TWO: CROSS-BORDER MOVEMENT FROM ZIMBABWE TO SOUTH AFRICA 2.1 INTRODUCTION 26 2.2 COPING WITH ECONOMIC HARDSHIPS IN ZIMBABWE 27 2.3 SURVEY METHODOLOGY 32 2.4 WHO GOES TO SOUTH AFRICA?33 2.5 TIMES OF TRAVEL 36 2.6 WHY DO THEY GOTOSOUTH AFRICA?39 2.7 CONCLUSION 40 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 41 CHAPTER THREE: ZIMBABWEAN ATTITUDES TO IMMIGRANTS, MIGRANTS AND REFUGEES 3.1 INTRODUCTION 42 3.2 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY 42 3.3 PROFILE OF THE SAMPLE -

The Magnetic Signature of Gold Bearing Rocks at Mphoengs

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN (Online): 2319-7064 Impact Factor (2012): 3.358 The Magnetic Signature of Gold Bearing Rocks at Mphoengs Bernard Siachingoma1, Simbarashe Chipokore2 1Geophysics Lecturer, Physics Department, Midlands State University, P/Bag 9055 Gweru, Zimbabwe 2Undergraduate Student, Physics Department, Midlands State University, P/Bag 9055 Gweru, Zimbabwe Abstract: Geophysics can make significant contribution to the life of mankind by skilfully helping in the precise location of valuable concealed ore deposits of economic value. The aim of this study was to conduct a geophysical survey using ground magnetics on NMPL north and south base metal blocks to detect disseminated sulphides which are associated with gold mineralisation located in Mphoengs, Bulilimamangwe District of Zimbabwe. More specifically it sought to generate anomaly maps of the study area with the ultimate aim of establishing beyond doubt regions with greater concentration of valuable gold deposits. A series of measurements were done and results presented as anomaly maps. The project is located within a narrow corridor of variably altered talcose horn blend-chlorite schist and serpentinites. This is a highly mineralized gold zone that has seen significant gold production in the past and shows potential for discovery of major gold resources in the future. The study area is located within a geologic setting considered highly prospective for the presence of a low tonnage high grade, bulk mineable gold deposit. The results really show the applicability of Physics to providing practical solutions to real problems. The established anomaly maps are usable by the project client to plan and zoom in on the most profitable regions of the surveyed area. -

Downloads SCSI News Letter July

JOURNAL OF SOIL AND WATER CONSERVATION NEW SERIES Vol. 15, No. 3 ISSN 0022–457X JULY-SEPTEMBER 2016 Contents Changes in vegetation cover and soil erosion in a forest watershed on removal of weed Lantana camara in 193 lower Shivalik region of Himalayas - PAWAN SHARMA, A.K. TIWARI, V.K. BHATT and K. SATHIYA Salt affected soils in Jammu and Kashmir: Their management for enhancing productivity 199 - R.D. GUPTA and SANJAY ARORA Runoff and soil loss estimation using hydrological models, remote sensing and GIS in Shivalik foothills: a review 205 - ABRAR YOUSUF and M. J. SINGH Irrigation water management strategies for wheat under sodic environment 211 - ATUL KUMAR SINGH, SANJAY ARORA, Y. P. SINGH, C. L. VERMA, A. K. BHARDWAJ and NAVNEET SHARMA Geosptatial technology in soil resource inventory and land capability assessment for sustainable 218 development – Wayanad District, Kerala - Y. SURESH KUMAR, N.S. GAHLOD and V.S. ARYA Impact of Albizia procera benth. based agroforestry system on soil quality in Bundelkhand region of Central India 226 - RAJENDRA PRASAD, RAM NEWAJ, V.D. TRIPATHI, N.K. SAROJ, PRASHANT SINGH, RAMESH SINGH, AJIT and O.P. CHATURVEDI Comparative study of reference evapotranspiration estimation methods including Artificial Neural Network for 233 dry sub-humid agro-ecological region - SASWAT KUMAR KAR, A.K. NEMA, ABHISHEK SINGH, B.L. SINHA and C.D. MISHRA Efficient use of jute agro textiles as soil conditioner to increase chilli productivity on inceptisol of West Bengal 242 - NABANITA ADHIKARI, ARIF DISHA, ANGIRA PRASAD MAHATA, ARUNABHA PAL, RAHUL ADHIKARI, MILAN SARDAR, ANANYA SAHA, SANJIB KUMAR BAURI, P. -

National Youth Service Training

National youth service training - “ shaping youths in a truly Zimbabwean manner” [COVER PICTURE] An overview of youth militia training and activities in Zimbabwe, October 2000 – August 2003 THE SOLIDARITY PEACE TRUST 5 September, 2003 Produced by: The Solidarity Peace Trust, Zimbabwe and South Africa Endorsed nationally by: Crisis in Zimbabwe Coalition Zimbabwe National Pastors Conference Ecumenical Support Services Harare Ecumenical Working Group Christians Together for Justice and Peace Endorsed internationally by: Physicians for Human Rights, Denmark The Solidarity Peace Trust has a Board consisting of church leaders of Southern Africa and is dedicated to promoting the rights of victims of human rights abuses in Zimbabwe. The Trust was founded in 2003. The Chairperson is Catholic Archbishop Pius Ncube of Bulawayo, and the Vice Chairperson is Anglican Bishop Rubin Phillip of Kwazulu Natal. email: selvanc@venturenet,co.za or [email protected] phone: + 27 (0) 83 556 1726 2 “Those who seek unity must not be our enemies. No, we say no to them, they must first repent…. They must first be together with us, speak the same language with us, act like us, walk alike and dream alike.” President Robert Mugabe [Heroes’ Day, 11 August 2003: referring to the MDC and the possibility of dialogue between MDC and ZANU-PF] 1 “…the mistake that the ruling party made was to allow colleges and universities to be turned into anti-Government mentality factories.” Sikhumbuzo Ndiweni [ZANU-PF Information and Publicity Secretary for Bulawayo]2 “[National service is] shaping youths in a truly Zimbabwean manner” Vice President Joseph Msika [July 2002, speech at graduation of 1,063 militia in Mt Darwin]3 1 The Herald, Harare, 12 August 2003. -

Rural District Planning in Zimbabwe: a Case Study

INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR ENVIRONMENT AND DEVELOPMENT Environmental Planning Issues No.23, December 2000 Local Strategic Planning and Sustainable Rural Livelihoods Rural District Planning in Zimbabwe: A Case Study By PlanAfric Bulawayo, Zimbabwe A Report to the UK Department for International Development (Research contract: R72510) PlanAfric Suite 416, 4th Floor, Treger House, 113 Jason Moyo Street PO Box FM 524, Famona, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe Tel/Fax: +263-9-66142; Email: [email protected] IIED 3 Endsleigh Street, London WC1H ODD Tel: +44-171-388-2117; Fax: +44-171-388-2826 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.iied.org ISBN: 1 899825 76 2 NOTE This manuscript was completed in November 1999. It has not been possible to include any updates to the text to reflect any changes that might have occurred in terms of legislation, institutional arrangements and key issues. RURAL PLANNING REPORTS This report is one of a suite of four prepared for a study of rural planning experience globally, and published by IIED in its Environmental Planning Issues series: Botchie G. (2000) Rural District Planning in Ghana: A Case Study. Environmental Planning Issues No. 21, Internationa l Institute for Environment and Development, London Dalal-Clayton, D.B., Dent D.L. and Dubois O. (1999): Rural Planning in the Developing World with a Special Focus on Natural Resources: Lessons Learned and Potential Contributions to Sustainable Livelihoods: An Overview. Report to UK Department for International Development. Environmental Planning Issues No.20, IIED, London Khanya-mrc (2000) Rural planning in South Africa: A case study. A report prepared by Khanya – managing rural change, Bloemfontein. -

A Case of Mopane Worms (Amacimbi) Harvesting

Incorporating Traditional Natural Resource Management Techniques in Conventional Natural Resources Management Strategies: A case of Mopane Worms (Amacimbi) Management and Harvesting in the Buliliamamangwe District, Zimbabwe Johnson Maviya and Davison Gumbo Abstract Strategies for poverty alleviation in much of Africa have been driven from outside in communities concerned. Potentials of natural resources under the jurisdiction of communities and their local level institutions have never been factored in these strategies. This paper explores the traditional natural resource management techniques by the Kalanga people of Bulilimamangwe District of Zimbabwe so that these could be incorporated in conventional management strategies by extension agencies. Currently, the level and extent of incorporating traditional management techniques in conventional resource management is low and restricted to Wildlife, yet management and harvesting of non-timber forest products such mopane worms could benefit from this research. The research reveals that certain specialized groups of families among the Kalanga people possess important knowledge in management and harvesting of the mopane worms which however has not been for incorporated into scientific resource management strategies by extension agencies. It is argued therefore that if such knowledge is factored into the scientific resource management techniques, the community, as well as the ecology of the area stand to benefit a lot. Introduction Strategies for poverty alleviation in much of Africa have -

Evaluattion of the Protracted Relief Programme Zimbabwe

Impact Evaluation of the Protracted Relief Programme II, Zimbabwe Final Report Prepared for // IODPARC is the trading name of International Organisation Development Ltd// Department for International Omega Court Development 362 Cemetery Road Sheffield Date //22/4/2013 S11 8FT United Kingdom By//Mary Jennings, Agnes Kayondo, Jonathan Kagoro, Tel: +44 (0) 114 267 3620 Kit Nicholson, Naomi Blight, www.iodparc.com Julian Gayfer. Contents Contents ii Acronyms iv Executive Summary vii Introduction 1 Approach and Methodology 2 Limitations of the Impact Evaluation 4 Context 6 Political and Economic context 6 Private sector and markets 7 Basic Service Delivery System 8 Gender Equality 8 Programme Implementation 9 Implementation Arrangements 9 Programme Scope and Reach 9 Shifts in Programme Approach 11 Findings 13 Relevance 13 Government strategies 13 Rationale for and extent of coverage across provinces, districts and wards 15 Donor Harmonisation 16 Climate change 16 Effectiveness of Livelihood Focussed Interventions 18 Graduation Framework 18 Contribution of Food Security Outputs to Effectiveness 20 Assets and livelihoods 21 Household income and savings 22 Contribution of Social Protection Outputs to Effectiveness 25 Contribution of WASH Outputs to Effectiveness 26 Examples of WASH benefits 28 Importance of Supporting Outputs to Effectiveness 29 Community Capacity 29 M&E System 30 Compliance 31 PRP Database 32 LIME Indices 35 Communications and Lesson Learning 35 Coordination 35 Government up-take at the different levels 37 Strategic Management