The Caribs of Dominica

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Political Change in Dominica, the Commonwealth West Indies. Cuthbert J

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1973 From crown colony to associate statehood : political change in Dominica, the Commonwealth West Indies. Cuthbert J. Thomas University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Thomas, Cuthbert J., "From crown colony to associate statehood : political change in Dominica, the Commonwealth West Indies." (1973). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 1879. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/1879 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ^^^^^^^ ^0 ASSOCIATE STATEHOOD: CHANGE POLITICAL IN DOMINICA, THE COMMONWEALTH WEST INDIES A Dissertation Presented By CUTHBERT J. THOMAS Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 1973 Major Subject Political Science C\ithbert J. Thomas 1973 All Rights Reserved FROM CROV/N COLONY TO ASSOCIATE STATEHOOD: POLITICAL CHANGE IN DOMINICA, THE COMMONWEALTH WEST INDIES A Dissertation By CUTHBERT J. THOMAS Approved as to stylq and content by; Dr. Harvey "T. Kline (Chairman of Committee) Dr. Glen Gorden (Head of Department) Dr» Gerard Braunthal^ (Member) C 1 Dro George E. Urch (Member) May 1973 To the Youth of Dominica who wi3.1 replace these colonials before long PREFACE My interest in Comparative Government dates back to ray days at McMaster University during the 1969-1970 academic year. -

Heritage Education — Memories of the Past in the Present Caribbean Social Studies Curriculum: a View from Teacher Practice Issue Date: 2019-05-28

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/73692 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation. Author: Con Aguilar E.O. Title: Heritage education — Memories of the past in the present Caribbean social studies curriculum: a view from teacher practice Issue Date: 2019-05-28 Chapter 6: The presence of Wai’tu Kubuli in teaching history and heritage in Dominica 6.1 Introduction Figure 6.1: Workshop at the Salybia Primary School Kalinago Territory, Dominica, January 2016. During my stay in Dominica, I had the opportunity to organize a teachers’ workshop with the assistance of the indigenous people of the Kalinago Territory. Although the teachers interact with Kalinago culture on a daily basis, we decided to explore the teachers’ knowledge of indigenous heritage and to challenge them in activities where they could put their knowledge into practice. We then drew animals, plants, tools and objects that are found in daily life in the Kalinago Territory. Later on in the workshop, we asked teachers about the Kalinago names that were printed on their tag names. Teachers were able to recognize some of these Kalinago names, and sometimes even the stories behind them. In this simple way, we started our workshop on indigenous history and heritage — because sometimes the most useful and meaningful learning resources are the ones we can find in our everyday life. This case study took place in Dominica; the island is also known by its Kalinago name, Wai’tu Kubuli, which means “tall is her body.” The Kalinago Territory is the home of the Kalinago people. -

Sales Manual

DominicaSALES MANUAL 1 www.DiscoverDominica.com ContentsINTRODUCTION LAND ACTIVITES 16 Biking / Dining GENERAL INFORMATION 29 Hiking and Adventure / 3 At a Glance Nightlife 4 The History 30 Shopping / Spa 4 Getting Here 31 Turtle Watching 6 Visitor Information LisT OF SERviCE PROviDERS RICH HERITAGE & CULTURE 21 Tour Operators from UK 8 Major Festivals & Special Events 22 Tour Operators from Germany 24 Local Ground Handlers / MAIN ACTIVITIES Operators 10 Roseau – Capital 25 Accommodation 18 The Roseau Valley 25 Car Rentals & Airlines 20 South & South-West 26 Water Sports 21 South-East Coast 2 22 Carib Territory & Central Forest Reserve 23 Morne Trois Pitons National Park & Heritage Site 25 North-East & North Coast Introduction Dominica (pronounced Dom-in-ee-ka) is an independent nation, and a member of the British Commonwealth. The island is known officially as the Commonwealth of Dominica. This Sales Manual is a compilation of information on vital aspects of the tourism slopes at night to the coastline at midday. industry in the Nature Island of Dominica. Dominica’s rainfall patterns vary as well, It is intended for use by professionals and depending on where one is on the island. others involved in the business of selling Rainfall in the interior can be as high as Dominica in the market place. 300 inches per year with the wettest months being July to November, and the As we continue our partnership with you, driest February to May. our cherished partners, please help us in our efforts to make Dominica more well known Time Zone among your clients and those wanting Atlantic Standard Time Zone, one hour information on our beautiful island. -

Multi-Hazard Early Warning Systems Gaps Report: Dominica, 2018

MULTI-HAZARD EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS GAPS ASSESSMENT REPORT FOR THE COMMONWEALTH OF DOMINICA, 2018 MULTI-HAZARD EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS GAPS REPORT: DOMINICA, 2018 Led by Dominica Emergency Management Organisation Director Mr. Fitzroy Pascal Author Gelina Fontaine (Local Consultant) National coordination John Walcott (UNDP Barbados & OECS) Marlon Clarke (UNDP Barbados & OECS) Regional coordination Janire Zulaika (UNDP – LAC) Art and design: Beatriz H.Perdiguero - Estudio Varsovia This document covers humanitarian aid activities implemented with the financial assistance of the European Union. The views expressed herein should not be taken, in any way, to reflect the official opinion of the European Union, and the European Commission is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains. UNDP CDEMA IFRC ECHO United Nations Caribbean Disaster International Federation European Civil Protection Development Emergency of the Red Cross and and Humanitarian Programme Management Agency Red Crescent Societies Aid Operations Map of Dominica. (Source Jan M. Lindsay, Alan L. Smith M. John Roobol and Mark V. Stasiuk Dominica, Chapter for Volcanic Hazards Atlas) CONTENTS 1. Executive Summary 2 2. Dominica Context 6 3. MHEWS Capacity and Assets 16 4. MHEWS Specific Gaps As It Relates To International Standards 24 27 4.1 Disaster Risk Knowledge Gaps DOMINICA OF 4.2 Disaster Risk Knowledge Recommendations 30 4.3 Gaps in detection, monitoring, analysis and forecasting 31 4.4 Recommendations for detection, monitoring, analysis and forecasting 35 4.5 Warning Dissemination and Communication Gaps 36 4.6 Recommendations for Warning Dissemination and Communication 38 4.7 Gaps in Preparedness and Response Capabilities 39 4.8 Recommendations for Preparedness and Response Capabilities 14 5. -

Demographic Statistics No.5

COMMONWEALTH OF DOMINICA DE,MOGRAP'HIC STAT~STICS NO.5 2008 ICENTRAL STATISTICAL OFFICE, Ministry of Finance and Social Security, Roseau, Dominica. Il --- CONTENTS PAGE Preface 1 Analysis ll-Xlll Explanatory Notes XIV Map (Population Zones) XV Map (Topography) xvi TABLES Non-Institutional Population at Census Dates (1901 - 2001) 1 2 Non-Institutional Population, Births and Deaths by Sex At Census Years (1960 - 200I) 2 3 Non-Institutional Population by Sex and Five Year Age Groups (1970,1981,1991, and 2001) 3 4 Non-Institutional Population By Five Year Age Groups (1970,1981, 1991 and 2001) 4 5 Population By Parishes (1946 - 200 I) 5 6 Population Percentage Change and Intercensal Annual Rate of Change (1881 - 200 I) 6 7 Population Density By Land Area - 200I Census compared to 1991 Census 7 8 Births and Deaths by Sex (1990 - 2006) 8 9 Total Population Analysed by Births, Deaths and Net Migration (1990 - 2006) 9 10 Total Persons Moving into and out ofthe Population (1981 -1990, 1991 - 2000 and 2001 - 2005) 10 II Number ofVisas issued to Dominicans for entry into the United States of America and the French Territories (1993 - 2003) 11 12 Mean Population and Vital Rates (1992 - 2006) 12 13 Total Births by Sex and Age Group ofMother (1996 - 2006) 13 14 Total Births by Sex and Health Districts (1996 - 2006) 14 15 Total Births by Age Group ofMother (1996 - 2006) 15 15A Age Specific Fertility Rates ofFemale Population 15 ~ 44 Years not Attending School 1981. 1991 and 2001 Census 16 16 Age Specific Birth Rates (2002 - 2006) 17 17 Basic Demographic -

Free Downloads Dominica Story a History of the Island

Free Downloads Dominica Story A History Of The Island Paperback Publisher: UNSPECIFIED VENDOR ASIN: B000UC3CTY Average Customer Review: 4.8 out of 5 stars  See all reviews (6 customer reviews) Best Sellers Rank: #15,367,898 in Books (See Top 100 in Books) #40 in Books > History > Americas > Caribbean & West Indies > Dominica #23428 in Books > Reference > Writing, Research & Publishing Guides > Writing > Travel Here is a very interesting history of a Caribbean island most people in the U.S. may not know much about. It's written by a native Dominican, Lennox Honychurch, who has himself participated in some of the events of his country in the last 30-40 years, particularly in the country's politics. And, despite that, he does a remarkable job of keeping the whole narrative very objective, even when a tragic portion of that history involves his own family. I also found the history of Britain and France fighting over the island between the 7 Years War and the Napoleonic Wars very exciting as well. Also, Mr. Honychurch mixes in enough ethnography and social observation to give anyone an idea of the general character of the people, even if they have never visited the island. However, I do have one or two critiques. First, about two-thirds of the way through the book, Mr. Honychurch switches from a purely chronological structure to a purely thematic structure then switches back within the last 30-40 pages. Not that I can think of a better way to do it, considering some of the things he had to cover, but it is a little jarring to have that kind of a structural switch. -

Correlating Monotonous Crystal-Rich Dacitic Ignimbrites in Dominica: the Layou and Roseau Ignimbrite Alexandra Flake Union College - Schenectady, NY

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2014 Correlating monotonous crystal-rich dacitic ignimbrites in Dominica: The Layou and Roseau Ignimbrite Alexandra Flake Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Geophysics and Seismology Commons, and the Volcanology Commons Recommended Citation Flake, Alexandra, "Correlating monotonous crystal-rich dacitic ignimbrites in Dominica: The Layou and Roseau Ignimbrite" (2014). Honors Theses. 519. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/519 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Correlating monotonous crystal-rich dacitic ignimbrites in Dominica: The Layou and Roseau Ignimbrite ----------------------------------------------------------- by Alexandra Flake Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science Department of Geology UNION COLLEGE June 2014 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my advisor Holli Frey for her guidance, support and wisdom throughout this entire process. She has taught me an incredible amount over the course of this thesis and most importantly has helped me grow as a student, scientist, and individual in and outside of the classroom. It was an amazing opportunity to work with her and made this thesis an incredibly rewarding experience. I would also like to thank Matthew Manon for running the ICP-MS, SEM and helping me throughout summer research, Bill Neubeck for making my sample thin sections, Deborah Klein for helping organize both trips down to Dominica, David Gillikin for inspiring me to become a geology major, and finally, the Union College Geology Department for financially supporting my multiple trips to Dominica to make this thesis possible. -

Power Relations and Good Governance: a Social Network Analysis of the Evolution of the Integrity in Public Office Act in the Commonwealth of Dominica

POWER RELATIONS AND GOOD GOVERNANCE: A SOCIAL NETWORK ANALYSIS OF THE EVOLUTION OF THE INTEGRITY IN PUBLIC OFFICE ACT IN THE COMMONWEALTH OF DOMINICA Thèse Gérard JEAN-JACQUES Doctorat en science politique Philosophiae doctor (Ph.D) Québec, Canada © Gérard Jean-Jacques, 2016 POWER RELATIONS AND GOOD GOVERNANCE: A SOCIAL NETWORK ANALYSIS OF THE EVOLUTION OF THE INTEGRITY IN PUBLIC OFFICE ACT IN THE COMMONWEALTH OF DOMINICA Thèse Gérard JEAN-JACQUES Sous la direction de: Louis IMBEAU, directeur de recherche Mathieu OUIMET, codirecteur de recherche RÉSUMÉ: La Banque mondiale propose la bonne gouvernance comme la stratégie visant à corriger les maux de la mauvaise gouvernance et de faciliter le développement dans les pays en développement (Carayannis, Pirzadeh, Popescu & 2012; & Hilyard Wilks 1998; Leftwich 1993; Banque mondiale, 1989). Dans cette perspective, la réforme institutionnelle et une arène de la politique publique plus inclusive sont deux stratégies critiques qui visent à établir la bonne gouvernance, selon la Banque et d'autres institutions de Bretton Woods. Le problème, c’est que beaucoup de ces pays en voie de développement ne possèdent pas l'architecture institutionnelle préalable à ces nouvelles mesures. Cette thèse étudie et explique comment un état en voie de développement, le Commonwealth de la Dominique, s’est lancé dans un projet de loi visant l'intégrité dans la fonction publique. Cette loi, la Loi sur l'intégrité dans la fonction publique (IPO) a été adoptée en 2003 et mis en œuvre en 2008. Cette thèse analyse les relations de pouvoir entre les acteurs dominants autour de évolution de la loi et donc, elle emploie une combinaison de technique de l'analyse des réseaux sociaux et de la recherche qualitative pour répondre à la question principale: Pourquoi l'État a-t-il développé et mis en œuvre la conception actuelle de la IPO (2003)? Cette question est d'autant plus significative quand nous considérons que contrairement à la recherche existante sur le sujet, l'IPO dominiquaise diverge considérablement dans la structure du l'IPO type idéal. -

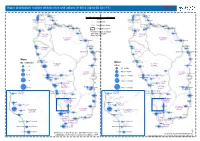

Water Distribution: Number of Deliveries and Volume in Litres (Up to 08 Oct '17) MA621 V2

Water distribution: number of deliveries and volume in litres (up to 08 Oct '17) MA621 v2 CapuchinDemetrie & Le Haut & Delaford CapuchinDemetrie & Le Haut & Delaford Penville 0 1.5 3 6 9 12 Penville Clifton L'Autre Bord Clifton L'Autre Bord Cottage & Cocoyer Vieille Case Kilometers Cottage & Cocoyer Vieille Case Toucari & Morne Cabrit !( Toucari & Morne Cabrit Savanne Paille & Tantan Settlements Savanne Paille & Tantan Moore Park EstaTtehibaud Moore Park EstaTtehibaud Paix Bouche Anse de Mai Major/Minor Road Paix Bouche Anse de Mai Belmanier Bense & HampsteaCd alibishie Belmanier Bense & HampsteaCd alibishie Dos D'Ane Woodford Hill Dos D'Ane Woodford Hill Lagon & De La Rosine Borne Parish Boundaries Lagon & De La Rosine Borne Portsmouth Portsmouth Population figure displayed Glanvillia Wesley Glanvillia Wesley ST. JOHN after Settlement and ST. JOHN Picard Picard 6561 PPL Parish Names 6561 PPL ST. ANDREW ST. ANDREW 9471 PPL Marigot & Concord 9471 PPL Marigot & Concord Dublanc Atkinson & Bataka Dublanc Atkinson & Bataka Bioche ST. PETER Bataka Bioche Bataka 1430 PPL ST. PETER Salybia & St. Cyr & Gaulette & Sineku 1430 PPL Salybia & St. Cyr & Gaulette & Sineku St. Cyr St. Cyr Colihaut Colihaut Gaulette Gaulette Sineku Sineku Water Coulibistrie Coulibistrie Morne Rachette Water Morne Rachette No. deliveries ST. JOSEPH ST. JOSEPH 5637 PPL Castle Bruce Litres Castle Bruce 1 - 2 Salisbury Salisbury 5637 PPL 13 - 8000 3 - 4 Belles Belles ST. DAVID 8001 - 16000 ST. DAVID 6043G PooPdL Hope & Dix Pais & Tranto 6043G PooPd LHope & Dix Pais & Tranto 5 - 6 St. Joseph Village Layou Valley Area St. Joseph Village Layou Valley Area San Sauveur 16001 - 24000 San Sauveur Layou Village Layou Village Warner Petite Soufriere Warner Petite Soufriere Tarou Tarou 7 - 8 Pond Casse 24001 - 32000 Pond Casse Campbell & Bon Repos Campbell & Bon Repos Jimmit Jimmit Mahaut ST. -

Island People

ISLAND PEOPLE [BIBLIOGRAPHY & FURTHER READING] JOSHUA JELLY-SCHAPIRO Island People: Bibliography and Further Reading www.joshuajellyschapiro.com ISLAND PEOPLE The Caribbean and the World By Joshua Jelly-Schapiro [Knopf 2016/Canongate 2017] Bibliography & Further Reading The direct source materials for Island People, and for quotations in the text not deriving from my own reporting and experience, are the works of history, fiction, film and music, along with primary documents from such archiVes as the West Indiana and Special Collections division at the University of the West Indies library in St. Augustine, Trinidad, enumerated in the “Notes” at the back of the book. But as essential to its chapters’ background, and to my explorations of indiVidual islands and their pasts, is a much larger body of literature—the wealth of scholarly and popular monographs on Antillean history and culture that occupy students and teachers in the burgeoning academic field of Caribbean Studies. What follows is a distilled account, more suggestiVe than comprehensiVe, of that bibliography’s essential entries, focusing on those books and other sources informing the stories and ideas contained in my book—and that comprise something like a list of Vital reading for those wishing to go further. Emphasis is here giVen to works in English, and to foreign-language texts that have been published in translation. Exceptions include those Spanish- and French- language works not yet published into English but which form an essential part of any good library on the islands in question. 1 Island People: Bibliography and Further Reading www.joshuajellyschapiro.com Introduction: The Caribbean in the World Start at the beginning. -

Dominica General Food Distribution Plan - 22/10/2017 Ç Ç ÇÇ Ç Ç Ç Ç Ç Ç United States Ç Ç a I Ç Bermuda Penville R Ç a Ç Ç M Ç Toucari Ç & Morne E Ç N 7 Ç

Dominica General Food Distribution Plan - 22/10/2017 Ç Ç ÇÇ Ç Ç Ç Ç Ç Ç United States Ç Ç a i Ç Bermuda Penville r Ç a Ç Ç M Ç Toucari Ç & Morne e Ç n 7 Ç Cabrit a The Bahamas 1 ÇÇ c 0 i Ç 2 Savanne Paille & Tantan r CubaTurks and CaÇicos Islands / r ÇÇÇ 9 u Ç Cayman Islands Ç 0 HaitiDominÇicÇan Republic Anse / H Jamaica Ç Puerto RÇicoGuadeloupe 9 de Mai f ÇÇ 1 Ç o DoÇminica Ç Belmanier Honduras Ç Bense & Calibishie f MartiniqÇuÇeÇ Lagon & De h o St. Lucia ÇÇ t Hampstead Nicaragua Aruba La Rosine Woodford a Grenada s a Hill P Trinidad and Tobago Colombia Venezuela Panama Guyana Saint John Wesley Saint Marigot & Andrew Concord Atkinson & Bataka Total targeted Bioche Saint population Peter 27,514 Salybia & St. Cyr & Gaulette & Sineku Total metric tons to be distributed 376 Coulibistrie Commodity MT Saint Rice, White, 231.85 Joseph medium grain Beans, dried 32.71 Oil, Vegetable [WFP] 18.55 Layou Saint Sardines, Canned In 34.76 Valley David Tomato Sauce, Area Drained Campbell & Total Total Bon Repos metric targeted Mahaut Saint Despor & Paul Sylvania tons to be popula�on Morne Riviere Jaune Cyrique Parish distributed Saint Trafalgar George St. Andrew 78.0 5,612 & Shawford Wotten St. David 29.3 2,664 Fond Waven Cole Potters Boetica St. George 144.4 10,101 Ville Yampiece Tarish Goodwill Pit Roseau St. John 24.2 1,577 Eggleston Victoria Kings Carib St. Joseph 20.4 1,329 Hill Giraudel Saint St. -

Dominica Water Food Distributio

DOMINICA: CN, FR, NL and VZ food and water distributions (as of 26 September 2017) 10P NL (26/09) 200L NL (26/09) 29P NL (25/09) 59P NL (25/09) 800L NL (25/09) 44P NL (25/09) La Haut !( Upper Demitrie! Penville 540L NL (25/09) Capuchin! Delaford!(!( 25P NL (25/09) !( Penville Lower L!('Autre Cli!fton Penville ! 260L NL (25/09) Cocoyer Bord ! !( !( Enbas 45P NL (25/09) Cottage Vi!eille 25P NL (26/09) ! Case!( Au Park Toucari !( Beryl Morne-a-Louis !( !( Guillet Gommier!( 1,333L NL (27/09) 120L NL (26/09) Tanetane !( ! Moor!e Park Thibaud Hampstead Estate !( 1,333L NL (27/09) Paix! A!nse Bouche de Mai Bense Calibishie Stowe !( Belmanier !( !( ! !( !( Grange Dos! Savane Woodford Lagon Borne D'Ane Paille ! 1,333L NL (27/09) !( !( Hill 360P NL (26/09) Portsmouth! ST. 20P DN (25/09) 8,930L NL (26/09) Glanvillia! JOHN W!esley 1,333L NL (27/09) Pi!card 5181 ST. Caye-En-Boucs Melville !( Hall ANDREW !( 120B NL (23/09) 8248 Marigot! 3,000L CN (25/09) 3,500L CN (26/09) 1,333L NL (27/09) Tanetane !( Dublanc! Atkinson! 1Pl CN (26/09) ST. Bataka Bio!che !( 84B NL (23/09) PETER Salybia !( 1598 Concorde St. Cyr 300B NL (23/09) !( !( Colihaut! Gaulette 62P NL (25/09) !( 1,300L NL (25/09) Sineku !( 2.5T FR (23/09) Couli!bistrie Morne! ST. 84B NL (23/09) Rachette 60B NL (23/09) JOSEPH Salisbury 1T FR (23/09) Castle! !( 5640 Bruce 2,400L NL (27/09) 45P DN (25/09) Tranto 350M NL (27/09) !(Morpo Belles !( Mero !( !( ST.