Introduction: the Geography of the Indian Ocean and Its Navigation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dijefori* Tvxt# Phone 828

t. wl HAVE COAL. COAL. TH* LARGEST AND ONLY HALL * WALKS* PADDED PURN1TURB < Wellington Colliery MOVING VANS IN TUB CITY. Co. IMS C.OVKK-VMEXT ST. Burt’s Wood Yard "X.: Phone 82 Dijefori* tvxt# Phone 828. Î38 Pandora Ave. VICTORIA, B. 0, THURSDAY, JUNE 17, 1909. NO. 137. VOLUME 47. the family were given a much larger THE HAWAIIAN STRIKE. amount. BIG BLAZE IN PLEASED PARTY THROWS LIGHT Wm. M. Hoag’s will also provided Aeletlc Merchente ol San Franctaro RUSSIANS OPEN FIRE that the 115,000 left to his brother should Are Making an Investigation. be Invested by the exécutons of the es PRAIRIE CAPITAL OF PUBLICISTS OH WALL STREET tate and only the income turned over, San Francisco, Cal., June 17.—Be to James A. Hong. He directed that ON BRITISH STEAMER lieving that Japanese strikers on the should James A. Hoag attempt to dis pose of this property held In trust for MANUFACTURING PLANT Hawaiian Islands sugar plantations do EASTERN WRITERS ARE COMMITTEE REPORTS the legatee’s sons after their father’s not deserve the assistance of their TO GENERAL HUGHES death, that the Income should be taken DESTROYED DT FIRE countrymen residing on this coast, a HERE AS C. P. R. GUESTS away from him and turned over to the committee of prominent Asiatic mer two sons. These sons were also left Captain Is Reported to Have Refused to Obey chants to-day sent K. Klyoee to Hono $2.000 eaçh. The principal bequests In the will Loss Placed at $700,000— lulu to make a report on the merits Entertained at Luncheon by Recommends Repeal of Char were $15,000. -

32 CFR Ch. V (7–1–06 Edition) § 578.51

§ 578.51 32 CFR Ch. V (7–1–06 Edition) (2) Permanently assigned as a mem- B–24 airplane flying overhead with a ber of a crew of a vessel sailing ocean sinking enemy submarine in the fore- waters for a period of 30 consecutive ground on three wave symbols, in the days or 60 nonconsecutive days. background a few buildings rep- (3) Outside the continental limits of resenting the arsenal of democracy, the United States in a passenger status above the scene the words ‘‘AMER- or on temporary duty for 30 consecu- ICAN CAMPAIGN’’. On the reverse an tive days or 60 nonconsecutive days. American bald eagle close between the (4) In active combat against the dates ‘‘1941–1945’’ and the words enemy and was awarded a combat deco- ‘‘UNITED STATES OF AMERICA’’. ration or furnished a certificate by the The ribbon is 13⁄8 inches wide and con- commanding general of a corps, higher sists of the following stripes: 3⁄16 inch unit, or independent force that the sol- Oriental Blue 67172; 1⁄16 inch White dier actually participated in combat. 67101; 1⁄16 inch Black 67138; 1⁄16 inch (5) Within the continental limits of Scarlet 67111; 1⁄16 inch White; 3⁄16 inch the United States for an aggregate pe- Oriental Blue; center 1⁄8 triparted Old riod of 1 year. Glory Blue 67178, White and Scarlet; 3⁄16 (b) The boundaries of American The- inch Oriental Blue; 1⁄16 inch White; 1⁄16 ater are as follows: inch Scarlet; 1⁄16 inch Black; 1⁄16 inch (1) Eastern boundary. -

Migration and Conservation: Frameworks, Gaps, and Synergies in Science, Law, and Management

GAL.MERETSKY.DOC 5/31/2011 6:00 PM MIGRATION AND CONSERVATION: FRAMEWORKS, GAPS, AND SYNERGIES IN SCIENCE, LAW, AND MANAGEMENT BY VICKY J. MERETSKY,* JONATHAN W. ATWELL** & JEFFREY B. HYMAN*** Migratory animals provide unique spectacles of cultural, ecological, and economic importance. However, the process of migration is a source of risk for migratory species as human actions increasingly destroy and fragment habitat, create obstacles to migration, and increase mortality along the migration corridor. As a result, many migratory species are declining in numbers. In the United States, the Endangered Species Act provides some protection against extinction for such species, but no protection until numbers are severely reduced, and no guarantee of recovery to population levels associated with cultural, ecological, or economic significance. Although groups of species receive some protection from statutes such as the Migratory Bird Treaty Act and Marine Mammal Protection Act, there is no coordinated system for conservation of migratory species. In addition, information needed to protect migratory species is often lacking, limiting options for land and wildlife managers who seek to support these species. In this Article, we outline the existing scientific, legal, and management information and approaches to migratory species. Our objective is to assess present capacity to protect the species and the phenomenon of migration, and we argue that all three disciplines are necessary for effective conservation. We find significant capacity to support conservation in all three disciplines, but no organization around conservation of migration within any discipline or among the three disciplines. Areas of synergy exist among the disciplines but not as a result of any attempt for coordination. -

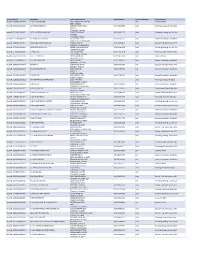

Contractor List

Active Licenses DBA Name Full Primary Address Work Phone # Licensee Category SIC Description buslicBL‐3205002/ 28/2020 1 ON 1 TECHNOLOGY 417 S ASSOCIATED RD #185 cntr Electrical Work BREA CA 92821 buslicBL‐1684702/ 28/2020 1ST CHOICE ROOFING 1645 SEPULVEDA BLVD (310) 251‐8662 subc Roofing, Siding, and Sheet Met UNIT 11 TORRANCE CA 90501 buslicBL‐3214602/ 28/2021 1ST CLASS MECHANICAL INC 5505 STEVENS WAY (619) 560‐1773 subc Plumbing, Heating, and Air‐Con #741996 SAN DIEGO CA 92114 buslicBL‐1617902/ 28/2021 2‐H CONSTRUCTION, INC 2651 WALNUT AVE (562) 424‐5567 cntr General Contractors‐Residentia SIGNAL HILL CA 90755‐1830 buslicBL‐3086102/ 28/2021 200 PSI FIRE PROTECTION CO 15901 S MAIN ST (213) 763‐0612 subc Special Trade Contractors, NEC GARDENA CA 90248‐2550 buslicBL‐0778402/ 28/2021 20TH CENTURY AIR, INC. 6695 E CANYON HILLS RD (714) 514‐9426 subc Plumbing, Heating, and Air‐Con ANAHEIM CA 92807 buslicBL‐2778302/ 28/2020 3 A ROOFING 762 HUDSON AVE (714) 785‐7378 subc Roofing, Siding, and Sheet Met COSTA MESA CA 92626 buslicBL‐2864402/ 28/2018 3 N 1 ELECTRIC INC 2051 S BAKER AVE (909) 287‐9468 cntr Electrical Work ONTARIO CA 91761 buslicBL‐3137402/ 28/2021 365 CONSTRUCTION 84 MERIDIAN ST (626) 599‐2002 cntr General Contractors‐Residentia IRWINDALE CA 91010 buslicBL‐3096502/ 28/2019 3M POOLS 1094 DOUGLASS DR (909) 630‐4300 cntr Special Trade Contractors, NEC POMONA CA 91768 buslicBL‐3104202/ 28/2019 5M CONTRACTING INC 2691 DOW AVE (714) 730‐6760 cntr General Contractors‐Residentia UNIT C‐2 TUSTIN CA 92780 buslicBL‐2201302/ 28/2020 7 STAR TECH 2047 LOMITA BLVD (310) 528‐8191 cntr General Contractors‐Residentia LOMITA CA 90717 buslicBL‐3156502/ 28/2019 777 PAINTING & CONSTRUCTION 1027 4TH AVE subc Painting and Paper Hanging LOS ANGELES CA 90019 buslicBL‐1920202/ 28/2020 A & A DOOR 10519 MEADOW RD (213) 703‐8240 cntr General Contractors‐Residentia NORWALK CA 90650‐8010 buslicBL‐2285002/ 28/2021 A & A HENINS, INC. -

Anti-Japanese Sentiment Inu.S. A

COAL. iWJfd. WOOD. WOOti. COAL. We heve the largest supply of GOOD HALL * WALK EH, AGENTS DRY WOOD In the City. FINE CliT Beet Nut end Household Cdel WCOD e specialty, 'fry us and ee Try ear Cemox eoel 1er fameoee. convinced. < • per cent, oft 1er cash with order. Burt’s Wood Yard IS*1 GOVERNMENT 8T. Phone MA SI PANDORA Am Phone tt. No. 43 VOL 47 VICTORIA, B. 0., SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 20, 1909. MARRIED HI8 NIECE. STEEL-COAL CONFERENCE. REVISION OF ANTI-JAPANESE Farmer Now Committed For Trial President» of Com pun le* Dl»< u»s De- Charged With Perjury In Ob ctslon pf Privy Council. taining License. SENTIMENT INU.S. A. Montreal. Que., Feb. 20. -Jas. Ross, VOTERS’ LISTS fSpeolal to the Times.) president of the Dominion Coa| Com Guelph. <mt.. Feb. 20. A. Mlnto pany. and J. H. Plummer, president of townahlu farmer named Samuel the Dominion Ir.«n arid Hteel Com HOljSE SPENDS WHOLE SITUATION REPRESENTED Roberte, married in November to his pany, had à conference yesterday In the Windsor hotel, in reference to the niece. Margaret Burton, by a Palmer AFTERNOON ON MAHER AS “MOST ALARMING" ston minister, has now been committed recent Judgment of the Judicial com mittee of the privy council. No defln- 'V miisisisiHi II Innm-IHUII mu». nn iimwin ■ itfwaiaMirtBrtjBi. k M£, ated Reports Are Be- RAILWAY Vl<T1M. ■w*vsawKiea»' - E ? inlcr Murray «f Nova Scot la. ^ing'CîrcïïlalHTifEmpîrè ’ ,s, ,rirî?»W9!r» It la stated that the Dominion Iron position Accepted -■tirmm has derided to ad- .........in Rgrt., ____________ tun over and killed by an engine in Company for the next six months ", tilt- yard* this morning. -

Parks Board Stays by Guns New

z COAL. COAL. ♦ W* HAVE THE LARGEST AND 01*1» BAIÆ A WALKER PADDED FURNITURE Wellington Colliery MOVING VANS CO. IN THE CITT. HIS GOVERNMENT ET. - Burt’s Wood Yard Phone SS Shorn 828. 736 Pindors Am VOLUME 47. VICTORIA, B. 0., THURSDAY, JUNE 24, 1909. NO; 143. BRYAN'S BON WEDS. WORK DELAYED. CRUSHED TO DEATH. TEXAS SENATOR Man Caught by Shaft in Pumping HUNT FOR LING PARKS BOARD Grand Lake. Colo., June 24.—Wm. KILLABNEY HAS Dispute Between Contractors Regard Station on Ranch. Jennings Bryfin. Jr., and Miss Helen ing Haulage of Material to Berger, of Milwaukee, were married STAYS BY GUNS here to-day. Only the Immediate rela BOAT DISASTER G. T.*P. Shops, ATTACKS TRUSTS Sacramento, Cal., June 24.—Mutilated IS UNABATERx tives of the couple were present. and stripped of Its clothing, the body Thé ceremony took place at the Ber Winnipeg. June 24.—Work on the of Joe. Nevis, aged 26 years, member FOLLOWS OLD BODY ger summer home here. The bride, ELEVEN PERSONS million dollar National Transconti WOULD SEND THE * of .a prominent family of this city, was RENEWED ACTIVITY who Is the daughter of Alexander Ber nental shops at Springfield is tempor found late last night wound around a_ ger. a millionaire grain tod hour arily tied up owing to • dispute be ORGANIZERS TO PRISON IN SAN FRANCISCO » IN FINANCIAL STAND dealer of Milwaukee, la very beautiful LOSE THEIR LIVES shaft in the pumping station on the and accomplished. She Is but IS year# tween contractors Haney, Quinlan and Nevis ranch in Yolo county. -

Eligibility Requirements

COAST GUARD COMBAT VETERANS ASSOCIATION ELIGIBILITY REQUIREMENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS HISTORIC AWARDS AND THEIR CRITERIA 1. KOREA WAR SERVICE MEDAL 1 2. VIETNAM SERVICE MEDAL 2 3. SOUTHWEST ASIA SERVICE MEDAL 3 4. ARMED FORCES EXPEDITIONARY MEDAL 4 thru 6 5. KOSOVO CAMPAIGN MEDAL 6, 7 6. AFGHANISTAN CAMPAIGN MEDAL 7 7. IRAQ CAMPAIGN MEDAL 8 thru 10 8. INHERENT RESOLVE CAMPAIGN MEDAL 10, 11 9. GLOBAL WAR ON TERRORISM EXPEDITIONARY MEDAL 11 thru 13 10. KOREAN DEFENSE SERVICE MEDAL 14 ADDITIONAL INFORMATION: AWARD INFORMATION, SPECIFICALLY FOR: ARMED FORCES EXPEDITIONARY MEDAL 15 thru 18 VIETNAM 19 thru 23 WORLD WAR II MEDALS AND AWARDS: AMERICAN CAMPAIGN MEDAL 24 EUROPE-AFRICA-MIDDLE EAST MEDAL 25 ASIATIC PACIFIC MEDAL 26 XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXCOMDTINST M1650.25E AWARDS FOR MEMBERSHIP IN THE COAST GUARD COMBAT VETERANS ASSOCIATION 1. Republic of Korea War Service Medal. The Republic of Korea War Service Medal was established in 1951 by the Republic of Korea (ROK) and offered to all service members who fought under the United Nations. U.S. law prohibited U.S. personnel from accepting the award at that time. On 20 August 1999, the Defense Department approved the acceptance and wear of the medal. a. Eligibility. Coast Guard personnel must have: (1) Served between the outbreak of hostilities, 25 June 1950, and the date the armistice was signed, 27 July 1953; (2) Been on permanent assignment or on temporary duty for 30 consecutive days or 60 non-consecutive days; and (3) Performed their duty within the territorial limits of Korea, in the waters immediately adjacent thereto or in aerial flight over Korea participating in actual combat operations or in support of combat operations. -

Betting Held to Be No Sin | Re-Enacts the Murder Of

WE HAVE COAL. COAL. THIS LARGEST AND ONLX HALL * WALKER padded furniture Wellington Colliery MOVING VANS Co. IN THE cm. I2S1 GOVERNMENT M, Burt's Wood Yard Phone M Fhone 838. 738 Pin dors An, NO. 142. VOLUME 47. VICTORIA, B. 0., WEDNESDAY, JUNE 23, 1909. VANCOUVER‘S OFFER. HARRIMAN'S illness. RUMORED DEATH OF | RE-ENACTS THE SEVERE ’(WAKES Businessmen May Purchase Michigan FOURTEEN ARE BETTING HELD Austrian Surgeon Says Magnate is Suf EMPEROR MENELIK tiuildlny at À.-Y.-P. Exposi fering From Nervous Aliment. MURDER OF GIRL IN CALIFORNIA tion. KILLED BY HEAT TO BE NO SIN Vienna. June 23.—Dr. Holxknechi, a Seattle, Wash., Juno 21.—Buslnesir- noted surgeon, is to-day In possession Report Which Has Been Re men of Vancouver. B. C.. have made a of an X-ray photograph of E. H. tentative offer to purchase the Michi Harrtman, the American railroad mag INTENSE SUFFERING REV. FATHER O’REILLY POLICE CONTINUE TO ceived at Rome is Not SHOCKS IN NORTHERN gan hulldlng at the exposition, and to nate. which he says shows that there assume the indebtedness on the struc is nothing radically wrong with the Credited. PART OF STATE ture. At a meeting of the Michigan IN NEW YORK CITY DEALS WITH QUESTION system of the distinguished patient. “SWEAT” CHINAMAN club last evening at the fair grounds /---------------- The surgeon says the photograph cor * ’ » the IniUdlng committee was given full roborates the statement of Professor power to act. in an address to the Streumpell, who is Harrlman’s phy (Times Leased Wire.) Residents of Grass Valley and Thousands Sleep in the Open Jesuit Priest Now in Victoria sician, that the railroad man Is suffer Hope to Secure Information Rome. -

State Ceremony at Westminster of Channel Fleet

.... ................... T ' Mm/>r\WW!). YirnnnWUUÜ. COAL. COAL. We hare the tersest ripply ot GOOD HALL * WALKER, AGENTS DRY WOOD ln the City FINE CÎTT Best Hut and Household CoaL WCOD a specialty. Try us and uo Try ear Como* coal for furnaces. convinced. • par cent off tor cash with order. Bupt’a Wood Yard 1SS1 GOVERNMENT 6T. Phone m si PANDORA AY*, VOL, 47 VICTORIA, B. 0., TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 16, 1909. No. 39 WATERWORKS STATE CEREMONY MANITOBA TO REDUCE AUSTRIA’S WAR LOAN AT WESTMINSTER TELEPHONE RATES OF 70 MILLIONS BILL DISCUSSED (Special to the Times) Winnipeg, Man., Feb. 16.— London. Fob. II.— A dispatch Hon. Hugh Armstrong delivered to the Chronicle from Vienna ESQUIMALT COMPANY . KING EDWARD OPENS his budget speech jn tke Ulgll t state* tl at Austria-Hungary laturv last evening, and an will shortly Issue a *$7 0, OOP. 000 WANTS PROTECTION BRITISH PARLIAMENT nounced that the profit* for the hloan at four |ier cent, in order .first year's" operation* »r a for-, to prejiaro foi any contingent y • «emnont-telephone were $166.000.. with -rcgird In Servis. This The government has decided to fund will apply to the- rcplentsh- Oak Bay and Saanich Desire Amicable Anglo-German Rela reduce the ‘phone rate* by one- infg of the wa,r treasury. third. City to Be Obliged to tions Alluded to in Speech Supply Them. From the Throne. FIVE STREETS The civic waterworks bill was befefre London,,Feb. lf.-A greater crowd RESIGNS COMMAND •then iwiWLaeUieffrt »t KW'-VlSE .n,nnm Tnm<f|t IK SIX Mm jltg the city ;<Wdh meat by King* tMewd, OF CHANNEL FLEET HiücUlar features. -

32 CFR Ch. V (7–1–06 Edition)

§ 578.51 32 CFR Ch. V (7–1–06 Edition) (2) Permanently assigned as a mem- B–24 airplane flying overhead with a ber of a crew of a vessel sailing ocean sinking enemy submarine in the fore- waters for a period of 30 consecutive ground on three wave symbols, in the days or 60 nonconsecutive days. background a few buildings rep- (3) Outside the continental limits of resenting the arsenal of democracy, the United States in a passenger status above the scene the words ‘‘AMER- or on temporary duty for 30 consecu- ICAN CAMPAIGN’’. On the reverse an tive days or 60 nonconsecutive days. American bald eagle close between the (4) In active combat against the dates ‘‘1941–1945’’ and the words enemy and was awarded a combat deco- ‘‘UNITED STATES OF AMERICA’’. ration or furnished a certificate by the The ribbon is 13⁄8 inches wide and con- commanding general of a corps, higher sists of the following stripes: 3⁄16 inch unit, or independent force that the sol- Oriental Blue 67172; 1⁄16 inch White dier actually participated in combat. 67101; 1⁄16 inch Black 67138; 1⁄16 inch (5) Within the continental limits of Scarlet 67111; 1⁄16 inch White; 3⁄16 inch the United States for an aggregate pe- Oriental Blue; center 1⁄8 triparted Old riod of 1 year. Glory Blue 67178, White and Scarlet; 3⁄16 (b) The boundaries of American The- inch Oriental Blue; 1⁄16 inch White; 1⁄16 ater are as follows: inch Scarlet; 1⁄16 inch Black; 1⁄16 inch (1) Eastern boundary. -

Lttl£S R Eid Ce Phone 8710

For Konst old Resu>vals Phono 121 CÔAL! COAL! BURT’S Hall & Walker 185 PANDORA 81. 1232 Government Street Podded Vans, Prompt Attention. ^Experienced Mr- lttl£S R eid ce Phone 8710. TELEPHONE S3. VOL. 51. VICTORIA. B. C., MONDAY, MARCH 27, 1911 No. 72 SECHELT WRECKAGE IS MINISTERS DEFEND PICKED UP IN STRAITS RECIPROCITY AGREEMENT Life-Boats, Doors, Planking and Other Articles Bon. W. S. Fielding and Hon. Sydney Fisher Speak From Ill-Fated Vessel are Found—Number at Montreal—People Beginning to Realize of Dead Uncertain. Benefit of Freer Trade. (tipeclal to the Times.) ciprocity had been.,a bolt from a blue to see the vessel sink, although sky* Mr. Fielding pointed out that the noticed that she gras faring badly Montreal. March 27.—Windsor Hall DROWNED * war crowded on Saturday evening when arrangements which wqre the founda passing the Race. tion for these later proceeding* were representative gathering heard Hon. Addition*! wreckage was picked adopted by thq unanimous vote of par yesterday afternoon by Richard Jack- Among the drowned are: W. g. Fielding and Hon. Sydney Fisher liament. son. of Admiral's road, who was out J. W. Burns, aged 50. of Sooke, defend the reciprocity agreement. cruising in the straits in his launch. Mr. Fielding asked why" the people of and Mrs Burns, his wife He picked up a door and a life-belt, the That a considerable portion of tin- Canada had been, prosperous of late, George King Newton, aged 2d. former at the entrance to the harbor audience was antagonist was shown and then quoted various figures to show the records for 14 years before 1896 and of Victoria, a surveyor. -

Commander's Think Tank

November 2015 www.vfw8874.org “Those Who Have Long Enjoyed Such Privileges As We Enjoy POST CALENDAR: Forget In Time That Men Have Died To Win Them.” SUNs World Tavern Poker 3:00PM MONs Monday Night Football 6:30PM ~ President Franklin D. Roosevelt ~ MONs Pool League 9-Ball 6:30PM TUEs Pool League 8-Ball 6:30PM VFW MISSION: WEDs World Tavern Poker 7:00PM The Veterans of Foreign Wars is an organization of war veterans committed FRI/SAT Free Pool All Day 2nd MONs VFW Aux Meetings 5:30PM to ensuring rights, remembering sacrifices, promoting patriotism, performing 3rd THUs VFW Member Meetings 6:00PM community services and advocating for a strong national defense. NOVEMBER COMMANDER’S THINK TANK: National Military Family Month Comrades, Deadline: Patriot’s Pen Essay NOV 1 Deadline: Voice of Democracy NOV 1 I wanted to make you aware of some upcoming events that our post will be VFW Auxiliary Meeting - 5:30PM NOV 2 participating in this month and early next month. First, we are very happy and Election Day NOV 3 proud to be hosting this year’s Los Alamos Veterans Day celebration. Our post, Veterans Day Committee - 6:30 NOV 5 as well as many other local fraternal organizations have been meeting for over a U.S. Marine Corps (USMC) B-Day NOV 10 Veteran’s Day (Event - Fuller Lodge) NOV 11 month to plan this event which will be held on Wednesday, November 11 at 11am VFW Meeting - 6PM NOV 19 at Fuller Lodge. This year’s event will be a little different, as we have partnered with Great American Smokeout NOV 19 Los Alamos County as they will be celebrating the signing of the Manhattan Project Thanksgiving NOV 26 National Historical Park on that same day, 10am at the LA Youth Center.