Breeding Ecology and Nest-Site Selection of Song Wrens in Central Panama

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

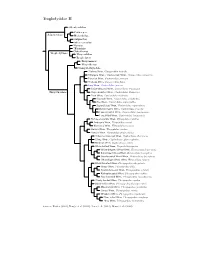

Troglodytidae Species Tree

Troglodytidae I Rock Wren, Salpinctes obsoletus Canyon Wren, Catherpes mexicanus Sumichrast’s Wren, Hylorchilus sumichrasti Nava’s Wren, Hylorchilus navai Salpinctinae Nightingale Wren / Northern Nightingale-Wren, Microcerculus philomela Scaly-breasted Wren / Southern Nightingale-Wren, Microcerculus marginatus Flutist Wren, Microcerculus ustulatus Wing-banded Wren, Microcerculus bambla ?Gray-mantled Wren, Odontorchilus branickii Odontorchilinae Tooth-billed Wren, Odontorchilus cinereus Bewick’s Wren, Thryomanes bewickii Carolina Wren, Thryothorus ludovicianus Thrush-like Wren, Campylorhynchus turdinus Stripe-backed Wren, Campylorhynchus nuchalis Band-backed Wren, Campylorhynchus zonatus Gray-barred Wren, Campylorhynchus megalopterus White-headed Wren, Campylorhynchus albobrunneus Fasciated Wren, Campylorhynchus fasciatus Cactus Wren, Campylorhynchus brunneicapillus Yucatan Wren, Campylorhynchus yucatanicus Giant Wren, Campylorhynchus chiapensis Bicolored Wren, Campylorhynchus griseus Boucard’s Wren, Campylorhynchus jocosus Spotted Wren, Campylorhynchus gularis Rufous-backed Wren, Campylorhynchus capistratus Sclater’s Wren, Campylorhynchus humilis Rufous-naped Wren, Campylorhynchus rufinucha Pacific Wren, Nannus pacificus Winter Wren, Nannus hiemalis Eurasian Wren, Nannus troglodytes Zapata Wren, Ferminia cerverai Marsh Wren, Cistothorus palustris Sedge Wren, Cistothorus platensis ?Merida Wren, Cistothorus meridae ?Apolinar’s Wren, Cistothorus apolinari Timberline Wren, Thryorchilus browni Tepui Wren, Troglodytes rufulus Troglo dytinae Ochraceous -

SPLITS, LUMPS and SHUFFLES Splits, Lumps and Shuffles Thomas S

>> SPLITS, LUMPS AND SHUFFLES Splits, lumps and shuffles Thomas S. Schulenberg Based on features including boot colour and tail shape, Booted Racket-tail Ocreatus underwoodii may be as many as four species. 1 ‘Anna’s Racket- tail’ O. (u.) annae, male, Cock-of-the-rock Lodge, 30 Neotropical Birding 22 Cuzco, Peru, August 2017 (Bradley Hacker). This series focuses on recent taxonomic proposals – descriptions of new taxa, splits, lumps or reorganisations – that are likely to be of greatest interest to birders. This latest instalment includes: new species of sabrewing, parrot (maybe), tapaculo, and yellow finch (perhaps); proposed splits in Booted Racket-tail, Russet Antshrike, White-backed Fire-eye (split city!), Collared Crescentchest, Olive-backed Foliage-gleaner, Musician Wren, Spotted Nightingale-Thrush, Yellowish and Short-billed Pipits, Black-and- rufous Warbling Finch, Pectoral and Saffron-billed Sparrows, and Unicolored Blackbird; a reassessment of an earlier proposed split in Black-billed Thrush; the (gasp!) possibility of the lump of South Georgia Pipit; and re- evaluations of two birds each known only from a single specimen. Racking up the racket-tails Venezuela to Bolivia; across its range, the puffy ‘boots’ (leg feathering) may be white or buffy, Booted Racket-tail Ocreatus underwoodii is one and the racket-tipped outer tail feathers may be of the most widespread, and one of the fanciest, straight, or so curved that the outermost rectrices hummingbirds of the Andes. It occurs from cross over one another. 2 ‘Peruvian’ Racket-tail O. (u.) peruanus, female, Abra Patricia, San Martín, Peru, October 2011 (Nick Athanas/antpitta.com). 3 ‘Peruvian Racket-tail’ O. -

Birds of the Río Negro Jaguar Preserve, Colonia Libertad, Costa Rica

C O T IN G A 8 Birds of the Río Negro Jaguar Preserve, Colonia Libertad, Costa Rica Daniel S. Cooper Cuando esté completa, Rio Negro Jaguar Preserve protegerá c. 10 000 acres de llanura y pedemonte de la vertiente caribeña junto al Parque Nacional Rincón de la Vieja en el noroeste de Costa Rica. Si bien el área posee pocos asentamientos y es aún remota, el reciente (desde comienzos de los ’80) y acelerado ritmo de tala y deforestación en la región ha hecho que estas selvas sean unas de las más amenazadas en el país. El hábitat en las cercanías de la reserva representa uno de los últimos grandes bloques de selva contigua de las llanuras hasta los niveles medios de elevación en Costa Rica, y, conectada a la selva de altura protegida en un parque nacional, funciona como un corredor forestal de dispersión, crucial para los movimientos altitudinales estacionales de las 300 especies de aves y varias docenas de mamíferos del área. Esta región poco habitada: no más de 2000 personas viven en sus alrededores, la mayoría de los cuales llegaron en los últimos 20 años, esta explotada a pequeña escala y así provee de un área núcleo de reserva para varias especies raras que han sido prácticamente eliminadas en sectores a menor altitud, como por ejemplo Electron carinatum y los globalmente casi-amenazados Spizastur melanoleucus, Chamaepetes unicolor, Odontophorus leucolaemus, Procnias tricarunculata, Piprites griseiceps y Buthraupis arcaei, todos los cuales han sido detectados cerca o arriba los 700 m. Se presenta una lista completa de especies, preparada como resultado de investigaciones entre el 12 marzo y 7 abril 1996 por el autor en el área alrededor de Colonia Libertad, dos visitas por T. -

TOP BIRDING LODGES of PANAMA with the Illinois Ornithological Society

TOP BIRDING LODGES OF PANAMA WITH IOS: JUNE 26 – JULY 5, 2018 TOP BIRDING LODGES OF PANAMA with the Illinois Ornithological Society June 26-July 5, 2018 Guides: Adam Sell and Josh Engel with local guides Check out the trip photo gallery at www.redhillbirding.com/panama2018gallery2 Panama may not be as well-known as Costa Rica as a birding and wildlife destination, but it is every bit as good. With an incredible diversity of birds in a small area, wonderful lodges, and great infrastructure, we tallied more than 300 species while staying at two of the best birding lodges anywhere in Central America. While staying at Canopy Tower, we birded Pipeline Road and other lowland sites in Soberanía National Park and spent a day in the higher elevations of Cerro Azul. We then shifted to Canopy Lodge in the beautiful, cool El Valle de Anton, birding the extensive forests around El Valle and taking a day trip to coastal wetlands and the nearby drier, more open forests in that area. This was the rainy season in Panama, but rain hardly interfered with our birding at all and we generally had nice weather throughout the trip. The birding, of course, was excellent! The lodges themselves offered great birding, with a fruiting Cecropia tree next to the Canopy Tower which treated us to eye-level views of tanagers, toucans, woodpeckers, flycatchers, parrots, and honeycreepers. Canopy Lodge’s feeders had a constant stream of birds, including Gray-cowled Wood-Rail and Dusky-faced Tanager. Other bird highlights included Ocellated and Dull-mantled Antbirds, Pheasant Cuckoo, Common Potoo sitting on an egg(!), King Vulture, Black Hawk-Eagle being harassed by Swallow-tailed Kites, five species of motmots, five species of trogons, five species of manakins, and 21 species of hummingbirds. -

Northern Peru Marañon Endemics & Marvelous Spatuletail 4Th to 25Th September 2016

Northern Peru Marañon Endemics & Marvelous Spatuletail 4th to 25th September 2016 Marañón Crescentchest by Dubi Shapiro This tour just gets better and better. This year the 7 participants, Rob and Baldomero enjoyed a bird filled trip that found 723 species of birds. We had particular success with some tricky groups, finding 12 Rails and Crakes (all but 1 being seen!), 11 Antpittas (8 seen), 90 Tanagers and allies, 71 Hummingbirds, 95 Flycatchers. We also found many of the iconic endemic species of Northern Peru, such as White-winged Guan, Peruvian Plantcutter, Marañón Crescentchest, Marvellous Spatuletail, Pale-billed Antpitta, Long-whiskered Owlet, Royal Sunangel, Koepcke’s Hermit, Ash-throated RBL Northern Peru Trip Report 2016 2 Antwren, Koepcke’s Screech Owl, Yellow-faced Parrotlet, Grey-bellied Comet and 3 species of Inca Finch. We also found more widely distributed, but always special, species like Andean Condor, King Vulture, Agami Heron and Long-tailed Potoo on what was a very successful tour. Top 10 Birds 1. Marañón Crescentchest 2. Spotted Rail 3. Stygian Owl 4. Ash-throated Antwren 5. Stripe-headed Antpitta 6. Ochre-fronted Antpitta 7. Grey-bellied Comet 8. Long-tailed Potoo 9. Jelski’s Chat-Tyrant 10. = Chestnut-backed Thornbird, Yellow-breasted Brush Finch You know it has been a good tour when neither Marvellous Spatuletail nor Long-whiskered Owlet make the top 10 of birds seen! Day 1: 4 September: Pacific coast and Chaparri Upon meeting, we headed straight towards the coast and birded the fields near Monsefue, quickly finding Coastal Miner. Our main quarry proved trickier and we had to scan a lot of fields before eventually finding a distant flock of Tawny-throated Dotterel; we walked closer, getting nice looks at a flock of 24 of the near-endemic pallidus subspecies of this cracking shorebird. -

Southern ECUADOR: Nov-Dec 2019 (Custom Tour)

Tropical Birding Trip Report Southern ECUADOR: Nov-Dec 2019 (custom tour) Southern Ecuador 18th November – 6th December 2019 Hummingbirds were a big feature of this tour; with 58 hummingbird species seen, that included some very rare, restricted range species, like this Blue-throated Hillstar. This critically-endangered species was only described in 2018, following its discovery a year before that, and is currently estimated to number only 150 individuals. This male was seen multiple times during an afternoon at this beautiful, high Andean location, and was widely voted by participants as one of the overall highlights of the tour (Sam Woods). Tour Leader: Sam Woods Photos: Thanks to participant Chris Sloan for the use of his photos in this report. 1 www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Tropical Birding Trip Report Southern ECUADOR: Nov-Dec 2019 (custom tour) Southern Ecuador ranks as one of the most popular South American tours among professional bird guides (not a small claim on the so-called “Bird Continent”!); the reasons are simple, and were all experienced firsthand on this tour… Ecuador is one of the top four countries for bird species in the World; thus high species lists on any tour in the country are a given, this is especially true of the south of Ecuador. To illustrate this, we managed to record just over 600 bird species on this trip (601) of less than three weeks, including over 80 specialties. This private group had a wide variety of travel experience among them; some had not been to South America at all, and ended up with hundreds of new birds, others had covered northern Ecuador before, but still walked away with 120 lifebirds, and others who’d covered both northern Ecuador and northern Peru, (directly either side of the region covered on this tour), still had nearly 90 new birds, making this a profitable tour for both “veterans” and “South American Virgins” alike. -

Tions by Mme E. V. Kozlova and Professor G. P. Dementiev. Mme

REVIEWS EDITED BY KENNETH C. PARKES A survey of the birds of Mongolia.--Charles Vaurie. 1964. Bull. Amer. Mus. Nat. Hist., 127 (3): 103-144, 1 pl., 2 text figs. $1.50.--Once again the English lan- guageliterature of ornithology has profired from Dr. Vaurie's excellentrelations with his Russian colleaguesand his unsurpassedknowledge of Palearctic zoogeography. The present publication is somethingof a miscellanybut all of its chapters bear on the ornithology of what used to be called Outer Mongolia and is now officially the Mongolian People'sRepublic. Dr. Vaurie was able to examine Mongolian specimens in Russian collections and was directed to (and given some) rare Russian publica- tions by Mme E. V. Kozlova and ProfessorG. P. Dementiev. Mme Kozlova has publishedthe major papers on the birds of this region, so little known to Americans. The first chapter is a descriptionof the physiographyand phytogeographyof Mon- golia, illustrated by two maps. One shows the physico-geographicdivisions of the countryas proposedby Murzaev, while a larger map showsthe phytogeographicand faunisticzones preferred by Vaurie. Statementsof distributionin the remainderof the paper are keyed to the zonesand localitieson this map. Then follows a list (binomials only) of the 333 speciesof birds recorded from Mongolia, with their rangeswithin the country. Vaurie apparentlyexpected that the secondvolume (non-passerines)of his Birds of the Palearcticfauna would have been publishedprior to the appearanceof the presentpaper, as it is cited in the text and listed in the bibliographywithout any statementthat it is in press. To someextent, therefore,this Mongolian list is a preview of the classificationof the non-passerines to be expectedin Vaurie's check-list. -

Panama's Canopy Tower and El Valle's Canopy Lodge

FIELD REPORT – Panama’s Canopy Tower and El Valle’s Canopy Lodge January 4-16, 2019 Orange-bellied Trogon © Ruthie Stearns Blue Cotinga © Dave Taliaferro Geoffroy’s Tamarin © Don Pendleton Ocellated Antbird © Carlos Bethancourt White-tipped Sicklebill © Jeri Langham Prepared by Jeri M. Langham VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DR., AUSTIN, TX 78746 Phone: 512-328-5221 or 800-328-8368 / Fax: 512-328-2919 [email protected] / www.ventbird.com Myriads of magazine articles have touted Panama’s incredible Canopy Tower, a former U.S. military radar tower transformed by Raúl Arias de Para when the U.S. relinquished control of the Panama Canal Zone. It sits atop 900-foot Semaphore Hill overlooking Soberania National Park. While its rooms are rather spartan, the food is Panama’s Canopy Tower © Ruthie Stearns excellent and the opportunity to view birds at dawn from the 360º rooftop Observation Deck above the treetops is outstanding. Twenty minutes away is the start of the famous Pipeline Road, possibly one of the best birding roads in Central and South America. From our base, daily birding outings are made to various locations in Central Panama, which vary from the primary forest around the tower, to huge mudflats near Panama City and, finally, to cool Cerro Azul and Cerro Jefe forest. An enticing example of what awaits visitors to this marvelous birding paradise can be found in excerpts taken from the Journal I write during every tour and later e- mail to participants. These are taken from my 17-page, January 2019 Journal. On our first day at Canopy Tower, with 5 of the 8 participants having arrived, we were touring the Observation Deck on top of Canopy Tower when Ruthie looked up and called my attention to a bird flying in our direction...it was a Black Hawk-Eagle! I called down to others on the floor below and we watched it disappear into the distant clouds. -

Peru: Manu and Machu Picchu August 2010

Peru: Manu and Machu Picchu August 2010 PERU: Manu and Machu Picchu 13 – 30 August 2010 Tour Leader: Jose Illanes Itinerary: August 13: Arrival day/ Night Lima August 14: Fly Lima-Cusco, Bird at Huacarpay Lake/ Night Cusco August 15: Upper Manu Road/Night Cock of the Rock Lodge August 16-17: San Pedro Area/ Nights cock of the Rock Lodge August 18: San Pedro-Atalaya/Night Amazonia Lodge August 19-20: Amazonia Lodge/Nights Amazonia Lodge August 21: River Trip to Manu Wildlife Center/Night Manu Wildlife Center August 22-24: Manu Wildlife Center /Nights Manu Wildlife Center August 25: Manu Wildlife Center - Boat trip to Puerto Maldonado/ Night Puerto Maldonado August 26: Fly Puerto Maldonado-Cusco/Night Ollantaytambo www.tropicalbirding.com Tropical Birding 1-409-515-0514 1 Peru: Manu and Machu Picchu August 2010 August 27: Abra Malaga Pass/Night Ollantaytambo August 28: Ollantaytambo-Machu Picchu/Night Aguas Calientes August 29: Aguas Calientes and return Cusco/Night Cusco August 30: Fly Cusco-Lima, Pucusana & Pantanos de Villa. Late evening departure. August 14 Lima to Cusco to Huacarpay Lake After an early breakfast in Peru’s capital Lima, we took a flight to the Andean city of Cusco. Soon after arriving in Cusco and meeting with our driver we headed out to Huacarpay Lake . Unfortunately our arrival time meant we got there when it was really hot, and activity subsequently low. Although we stuck to it, and slowly but surely, we managed to pick up some good birds. On the lake itself we picked out Puna Teal, Speckled and Cinnamon Teals, Andean (Slate-colored) Coot, White-tufted Grebe, Andean Gull, Yellow-billed Pintail, and even Plumbeous Rails, some of which were seen bizarrely swimming on the lake itself, something I had never seen before. -

New Bird Distributional Data from Cerro Tacarcuna, with Implications for Conservation in the Darién Highlands of Colombia

Luis Miguel Renjifo et al. 46 Bull. B.O.C. 2017 137(1) New bird distributional data from Cerro Tacarcuna, with implications for conservation in the Darién highlands of Colombia by Luis Miguel Renjifo, Augusto Repizo, Juan Miguel Ruiz-Ovalle, Sergio Ocampo & Jorge Enrique Avendaño Received 25 September 2016; revised 20 January 2017; published 13 March 2017 Summary.―We conducted an ornithological survey of the Colombian slope of Cerro Tacarcuna, the highland region adjacent to the ‘Darién Gap’ on the Colombia / Panama border, and one of the most poorly known and threatened regions in the world. We present novel data on distribution, habitat, breeding biology and vocalisations for 27 species, including the first confirmed records in Colombia of Ochraceous Wren Troglodytes ochraceus and Beautiful Treerunner Margarornis bellulus, and the first records in the Darién highlands of Black-headed Antthrush Formicarius nigricapillus, Scaly-throated Foliage-gleaner Anabacerthia variegaticeps, Yellow-throated Chlorospingus Chloropingus flavigularis hypophaeus and, based on previously overlooked specimens, report the first confirmed records for Colombia of Sooty-faced Finch Arremon crassirostris. In addition, we collected the first Colombian specimens of Violet-capped Hummingbird Goldmania violiceps, Bare- shanked Screech Owl Megascops clarkii, Tacarcuna Tapaculo Scytalopus panamensis and Varied Solitaire Myadestes coloratus. For several subspecies endemic to the region, we collected the first or second specimens for Colombia. Finally, we discuss the elevational ranges of Darién endemic species and subspecies, which are mostly concentrated above 600 m. The Darién highlands remain poorly studied and threats to their conservation are increasing. Therefore, effective measures are needed, particularly in Colombia, where the sole protected area in the region currently covers forests only below 600 m. -

Troglodytidae Tree, Part 2

Troglodytidae II Odontorchilus Catherpes Salpinctinae Hylorchilus Salpinctes Microcerculus Nannus ?Ferminia Cistothorus Troglo dytinae Thryorchilus Troglo dytes Thryomanes Thryothorus Campylorhynchus ?Rufous Wren, Cinnycerthia unirufa ?Sharpe’s Wren / Sepia-brown Wren, Cinnycerthia olivascens Peruvian Wren, Cinnycerthia peruana ?Fulvous Wren, Cinnycerthia fulva Gray Wren, Cantorchilus griseus Stripe-throated Wren, Cantorchilus leucopogon Thryothorinae Stripe-breasted Wren, Cantorchilus thoracicus Plain Wren, Cantorchilus modestus Riverside Wren, Cantorchilus semibadius Bay Wren, Cantorchilus nigricapillus Superciliated Wren, Cantorchilus superciliaris Buff-breasted Wren, Cantorchilus leucotis Fawn-breasted Wren, Cantorchilus guarayanus Long-billed Wren, Cantorchilus longirostris Rufous-and-white Wren, Thryophilus rufalbus Antioquia Wren, Thryophilus sernai Niceforo’s Wren, Thryophilus nicefori Sinaloa Wren, Thryophilus sinaloa Banded Wren, Thryophilus pleurostictus ?Chestnut-breasted Wren, Cyphorhinus thoracicus ?Song Wren, Cyphorhinus phaeocephalus Musician Wren, Cyphorhinus arada White-bellied Wren, Uropsila leucogastra White-breasted Wood-Wren, Henicorhina leucosticta Bar-winged Wood-Wren, Henicorhina leucoptera Gray-breasted Wood-Wren, Henicorhina leucophrys ?Munchique Wood-Wren, Henicorhina negreti Black-throated Wren, Pheugopedius atrogularis Happy Wren, Pheugopedius felix Speckle-breasted Wren, Pheugopedius sclateri Rufous-breasted Wren, Pheugopedius rutilus Spot-breasted Wren, Pheugopedius maculipectus ?Sooty-headed Wren, Pheugopedius spadix Black-bellied Wren, Pheugopedius fasciatoventris Moustached Wren, Pheugopedius genibarbis Coraya Wren, Pheugopedius coraya Whiskered Wren, Pheugopedius mystacalis Plain-tailed Wren, Pheugopedius euophrys ?Inca Wren, Pheugopedius eisenmanni Sources: Barker (2004), Dingle et al. (2006), Lara et al. (2012), Mann et al. (2006).. -

AOU Check-List Supplement

AOU Check-list Supplement The Auk 117(3):847–858, 2000 FORTY-SECOND SUPPLEMENT TO THE AMERICAN ORNITHOLOGISTS’ UNION CHECK-LIST OF NORTH AMERICAN BIRDS This first Supplement since publication of the 7th Icterus prosthemelas, Lonchura cantans, and L. atricap- edition (1998) of the AOU Check-list of North American illa); (3) four species are changed (Caracara cheriway, Birds summarizes changes made by the Committee Glaucidium costaricanum, Myrmotherula pacifica, Pica on Classification and Nomenclature between its re- hudsonia) and one added (Caracara lutosa) by splits constitution in late 1998 and 31 January 2000. Be- from now-extralimital forms; (4) four scientific cause the makeup of the Committee has changed sig- names of species are changed because of generic re- nificantly since publication of the 7th edition, it allocation (Ibycter americanus, Stercorarius skua, S. seems appropriate to outline the way in which the maccormicki, Molothrus oryzivorus); (5) one specific current Committee operates. The philosophy of the name is changed for nomenclatural reasons (Baeolo- Committee is to retain the present taxonomic or dis- phus ridgwayi); (6) the spelling of five species names tributional status unless substantial and convincing is changed to make them gramatically correct rela- evidence is published that a change should be made. tive to the generic name (Jacamerops aureus, Poecile The Committee maintains an extensive agenda of atricapilla, P. hudsonica, P. cincta, Buarremon brunnein- potential action items, including possible taxonomic ucha); (7) one English name is changed to conform to changes and changes to the list of species included worldwide use (Long-tailed Duck), one is changed in the main text or the Appendix.