Kristina Von Held

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

029I-HMVCX1924XXX-0000A0.Pdf

This Catalogue contains all Double-Sided Celebrity Records issued up to and including March 31st, 1924. The Single-Sided Celebrity Records are also included, and will be found under the records of the following artists :-CLARA Burr (all records), CARUSO and MELBA (Duet 054129), CARUSO,TETRAZZINI, AMATO, JOURNET, BADA, JACOBY (Sextet 2-054034), KUBELIK, one record only (3-7966), and TETRAZZINI, one record only (2-033027). International Celebrity Artists ALDA CORSI, A. P. GALLI-CURCI KURZ RUMFORD AMATO CORTOT GALVANY LUNN SAMMARCO ANSSEAU CULP GARRISON MARSH SCHIPA BAKLANOFF DALMORES GIGLI MARTINELLI SCHUMANN-HEINK BARTOLOMASI DE GOGORZA GILLY MCCORMACK Scorn BATTISTINI DE LUCA GLUCK MELBA SEMBRICH BONINSEGNA DE' MURO HEIFETZ MOSCISCA SMIRN6FF BORI DESTINN HEMPEL PADEREWSKI TAMAGNO BRASLAU DRAGONI HISLOP PAOLI TETRAZZINI BI1TT EAMES HOMER PARETO THIBAUD CALVE EDVINA HUGUET PATTt WERRENRATH CARUSO ELMAN JADLOWKER PLANCON WHITEHILL CASAZZA FARRAR JERITZA POLI-RANDACIO WILLIAMS CHALIAPINE FLETA JOHNSON POWELL ZANELLIi CHEMET FLONZALEY JOURNET RACHM.4NINOFF ZIMBALIST CICADA QUARTET KNIIPFER REIMERSROSINGRUFFO CLEMENT FRANZ KREISLER CORSI, E. GADSKI KUBELIK PRICES DOUBLE-SIDED RECORDS. LabelRed Price6!-867'-10-11.,613,616/- (D.A.) 10-inch - - Red (D.B.) 12-inch - - Buff (D.J.) 10-inch - - Buff (D.K.) 12-inch - - Pale Green (D.M.) 12-inch Pale Blue (D.O.) 12-inch White (D.Q.) 12-inch - SINGLE-SIDED RECORDS included in this Catalogue. Red Label 10-inch - - 5'676 12-inch - - Pale Green 12-inch - 10612,615j'- Dark Blue (C. Butt) 12-inch White (Sextet) 12-inch - ALDA, FRANCES, Soprano (Ahl'-dah) New Zealand. She Madame Frances Aida was born at Christchurch, was trained under Opera Comique Paris, Since Marcltesi, and made her debut at the in 1904. -

Annäherungen an Alma Mahler-Werfel (1)

Musikstunde „Sie war wie ein Vulkan!“ Annäherungen an Alma Mahler-Werfel (1) Von Susanne Herzog Sendung: 18. Februar 2019 Redaktion: Dr. Ulla Zierau Produktion: 2015 SWR2 können Sie auch als Live-Stream hören im SWR2 Webradio unter www.SWR2.de, auf Mobilgeräten in der SWR2 App, oder als Podcast nachhören: Bitte beachten Sie: Das Manuskript ist ausschließlich zum persönlichen, privaten Gebrauch bestimmt. Jede weitere Vervielfältigung und Verbreitung bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Urhebers bzw. des SWR. Kennen Sie schon das Serviceangebot des Kulturradios SWR2? Mit der kostenlosen SWR2 Kulturkarte können Sie zu ermäßigten Eintrittspreisen Veranstaltungen des SWR2 und seiner vielen Kulturpartner im Sendegebiet besuchen. Mit dem Infoheft SWR2 Kulturservice sind Sie stets über SWR2 und die zahlreichen Veranstaltungen im SWR2- Kulturpartner-Netz informiert. Jetzt anmelden unter 07221/300 200 oder swr2.de Die neue SWR2 App für Android und iOS Hören Sie das SWR2 Programm, wann und wo Sie wollen. Jederzeit live oder zeitversetzt, online oder offline. Alle Sendung stehen sieben Tage lang zum Nachhören bereit. Nutzen Sie die neuen Funktionen der SWR2 App: abonnieren, offline hören, stöbern, meistgehört, Themenbereiche, Empfehlungen, Entdeckungen … Kostenlos herunterladen: www.swr2.de/app SWR2 Musikstunde mit Susanne Herzog 18. Februar – 23. Februar 2019 „Sie war wie ein Vulkan!“ Annäherungen an Alma Mahler-Werfel (1) Mit Susanne Herzog. „Sie war wie ein Vulkan“ hat Anna Mahler über ihre Mutter Alma Mahler-Werfel gesagt und ihre „Begeisterungsfähigkeit für alles Künstlerische“ betont. Den Facetten der schillernden Persönlichkeit von Alma Mahler-Werfel und ihren Beziehungen zu so vielen großen Künstlern des 20. Jahrhunderts ist die SWR 2 Musikstunde diese Woche auf der Spur. -

Gustav Mahler : Conducting Multiculturalism

GUSTAV MAHLER : CONDUCTING MULTICULTURALISM Victoria Hallinan 1 Musicologists and historians have generally paid much more attention to Gustav Mahler’s famous career as a composer than to his work as a conductor. His choices in concert repertoire and style, however, reveal much about his personal experiences in the Austro-Hungarian Empire and his interactions with cont- emporary cultural and political upheavals. This project examines Mahler’s conducting career in the multicultural climate of late nineteenth-century Vienna and New York. It investigates the degree to which these contexts influenced the conductor’s repertoire and questions whether Mahler can be viewed as an early proponent of multiculturalism. There is a wealth of scholarship on Gustav Mahler’s diverse compositional activity, but his conducting repertoire and the multicultural contexts that influenced it, has not received the same critical attention. 2 In this paper, I examine Mahler’s connection to the crumbling, late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century depiction of the Austro-Hungarian Empire as united and question whether he can be regarded as an exemplar of early multiculturalism. I trace Mahler’s career through Budapest, Vienna and New York, explore the degree to which his repertoire choices reflected the established opera canon of his time, or reflected contemporary cultural and political trends, and address uncertainties about Mahler’s relationship to the various multicultural contexts in which he lived and worked. Ultimately, I argue that Mahler’s varied experiences cannot be separated from his decisions regarding what kinds of music he believed his audiences would want to hear, as well as what kinds of music he felt were relevant or important to share. -

Albums Are Dead - Sell Singles

The Journal of Business, Entrepreneurship & the Law Volume 4 Issue 1 Article 8 11-20-2010 Notice: Albums Are Dead - Sell Singles Brian P. Nestor Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/jbel Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons Recommended Citation Brian P. Nestor, Notice: Albums Are Dead - Sell Singles, 4 J. Bus. Entrepreneurship & L. Iss. 1 (2010) Available at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/jbel/vol4/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Caruso School of Law at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Journal of Business, Entrepreneurship & the Law by an authorized editor of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. NOTICE: ALBUMS ARE DEAD - SELL SINGLES BRIAN P. NESTOR * I. The Prelude ........................................................................................................ 221 II. Here Lies The Major Record Labels ................................................................ 223 III. The Invasion of The Single ............................................................................. 228 A. The Traditional View of Singles .......................................................... 228 B. Numbers Don’t Lie ............................................................................... 229 C. An Apple A Day: The iTunes Factor ................................................... 230 D. -

The Poetics of Reflection in Digital Games

© Copyright 2019 Terrence E. Schenold The Poetics of Reflection in Digital Games Terrence E. Schenold A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2019 Reading Committee: Brian M. Reed, Chair Leroy F. Searle Phillip S. Thurtle Program Authorized to Offer Degree: English University of Washington Abstract The Poetics of Reflection in Digital Games Terrence E. Schenold Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Brian Reed, Professor English The Poetics of Reflection in Digital Games explores the complex relationship between digital games and the activity of reflection in the context of the contemporary media ecology. The general aim of the project is to create a critical perspective on digital games that recovers aesthetic concerns for game studies, thereby enabling new discussions of their significance as mediations of thought and perception. The arguments advanced about digital games draw on philosophical aesthetics, media theory, and game studies to develop a critical perspective on gameplay as an aesthetic experience, enabling analysis of how particular games strategically educe and organize reflective modes of thought and perception by design, and do so for the purposes of generating meaning and supporting expressive or artistic goals beyond amusement. The project also provides critical discussion of two important contexts relevant to understanding the significance of this poetic strategy in the field of digital games: the dynamics of the contemporary media ecology, and the technological and cultural forces informing game design thinking in the ludic century. The project begins with a critique of limiting conceptions of gameplay in game studies grounded in a close reading of Bethesda's Morrowind, arguing for a new a "phaneroscopical perspective" that accounts for the significance of a "noematic" layer in the gameplay experience that accounts for dynamics of player reflection on diegetic information and its integral relation to ergodic activity. -

Paul Anka 21 Golden Hits Rar

Paul Anka 21 Golden Hits Rar Paul Anka 21 Golden Hits Rar 1 / 3 Quality: FLAC (Tracks) Artist: Various Artists Title: Yesterdays Gold: 120 Golden Oldies Volume 1-5 Released: 1987 Style: Pop, Rock RAR Size: 7.. Featured are two original albums in their entirety ‘Neil Sedaka’ and ‘Circulate’ plus the hits “I Go Ape”, “Oh Carol”, “Stairway To Heaven” and more.. Results 1 - 35 - Get golden hit songs [Full] Sponsored Links Golden hit songs full. 1. paul anka golden hits 2. paul anka's 21 golden hits vinyl 3. paul anka 21 golden hits songs Paul Anka - 21 Golden Hits 1963 mp3@192kbpsalE13 Download Torrent Paul Anka - 21 Golden Hits 1963.. 1- 10 Of 25) Dinah Washington 02 - Paul Anka - Put Your Head On Aug 13, 2016 - PAUL ANKA - He Made It Happen / 20 Greatest Hits 1988. paul anka golden hits paul anka golden hits, paul anka 21 golden hits, paul anka's 21 golden hits vinyl, paul anka 21 golden hits youtube, paul anka 21 golden hits songs, paul anka 21 golden hits 1963 full album, paul anka 21 golden hits download Mount And Blade Warband Female Character Creation rar - [FullVersion] Paul anka 1963 21 golden hits (72 46 MB) download Penyanyi: [ALBUM] Paul Anka - 21 Golden Hits (1963) [FLAC] Judul lagu.. Bill Haley & His Comets – Rock Around the Clock (02:13) 06 Johnnie Ray – Just Walking in the Rain (02:39) 07.. FREE DOWNLOAD ALBUM RAR FLAC VA - Yesterday's Gold Collection - Golden Oldies (Vol.. uk: MP3 Downloads 21 Golden Hits: Paul Anka uk: MP3 Downloads uk Try Prime Digital Music Go. -

JLGC NEWSLETTER Japan Local Government Center ( CLAIR, New York ) Issue No.81 March 2015

MARCH 2015 ISSUE #81 JLGC NEWSLETTER Japan Local Government Center ( CLAIR, New York ) Issue No.81 March 2015 CLAIR Fellowship Exchange Program 2014 was held from October 19 to October 29 in 2014 This program has been affording senior state and local government officials an opportunity CLAIR FELLOWSHIP to experience Japanese EXCHANGE PROGRAM 2014 government admin- ISSUE NO.81 MARCH 2015 istration first hand. This year the program was held in Tokyo and CLAIR Fellowship Exchange Amagasaki City, Hyogo Program 2014 was held from Prefecture. October 19 to October 29 in 2014 (Page1-6) Theme: Promotion of the tourism industry Amagasaki City is known as an industrial city, but not well known as tourist New York Times Travel destination. Now, promoting tourism in Amagasaki City has become an im- Show 2015 (Page7) portant issue, improving not only the local economy but also reenergizing the local communities. They would like to exchange opinions and share infor- mation about promoting tourism with senior officials who have experience or Japan Week 2015 (Page8-10) knowledge in the field. Participants exchanged their opinions, especially on the tourism industry. Also What Japanese food do you they experienced home-stays and traditional Japanese culture. like best? (Page11) JAPAN LOCAL GOVERNMENT CENTER (CLAIR, NY) 3 Park Avenue, 20th Floor New York, NY 10016-5902 212.246.5542 office • 212.246.5617 fax www.jlgc.org 1 MARCH 2015 ISSUE #81 Ms. Michelle Smibert Mr. Bob Gatt President, Association of Mayor, City of Novi, MI Municipal Managers, Clerks and Treasurers of Ontario In October, 2014, I set out for a trip of a lifetime. -

The Devils' Dance

THE DEVILS’ DANCE TRANSLATED BY THE DEVILS’ DANCE HAMID ISMAILOV DONALD RAYFIELD TILTED AXIS PRESS POEMS TRANSLATED BY JOHN FARNDON The Devils’ Dance جينلر بازمي The jinn (often spelled djinn) are demonic creatures (the word means ‘hidden from the senses’), imagined by the Arabs to exist long before the emergence of Islam, as a supernatural pre-human race which still interferes with, and sometimes destroys human lives, although magicians and fortunate adventurers, such as Aladdin, may be able to control them. Together with angels and humans, the jinn are the sapient creatures of the world. The jinn entered Iranian mythology (they may even stem from Old Iranian jaini, wicked female demons, or Aramaic ginaye, who were degraded pagan gods). In any case, the jinn enthralled Uzbek imagination. In the 1930s, Stalin’s secret police, inveigling, torturing and then executing Uzbekistan’s writers and scholars, seemed to their victims to be the latest incarnation of the jinn. The word bazm, however, has different origins: an old Iranian word, found in pre-Islamic Manichaean texts, and even in what little we know of the language of the Parthians, it originally meant ‘a meal’. Then it expanded to ‘festivities’, and now, in Iran, Pakistan and Uzbekistan, it implies a riotous party with food, drink, song, poetry and, above all, dance, as unfettered and enjoyable as Islam permits. I buried inside me the spark of love, Deep in the canyons of my brain. Yet the spark burned fiercely on And inflicted endless pain. When I heard ‘Be happy’ in calls to prayer It struck me as an evil lure. -

Marie Collier: a Life

Marie Collier: a life Kim Kemmis A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History The University of Sydney 2018 Figure 1. Publicity photo: the housewife diva, 3 July 1965 (Alamy) i Abstract The Australian soprano Marie Collier (1927-1971) is generally remembered for two things: for her performance of the title role in Puccini’s Tosca, especially when she replaced the controversial singer Maria Callas at late notice in 1965; and her tragic death in a fall from a window at the age of forty-four. The focus on Tosca, and the mythology that has grown around the manner of her death, have obscured Collier’s considerable achievements. She sang traditional repertoire with great success in the major opera houses of Europe, North and South America and Australia, and became celebrated for her pioneering performances of twentieth-century works now regularly performed alongside the traditional canon. Collier’s experiences reveal much about post-World War II Australian identity and cultural values, about the ways in which the making of opera changed throughout the world in the 1950s and 1960s, and how women negotiated their changing status and prospects through that period. She exercised her profession in an era when the opera industry became globalised, creating and controlling an image of herself as the ‘housewife-diva’, maintaining her identity as an Australian artist on the international scene, and developing a successful career at the highest level of her artform while creating a fulfilling home life. This study considers the circumstances and mythology of Marie Collier’s death, but more importantly shows her as a woman of the mid-twentieth century navigating the professional and personal spheres to achieve her vision of a life that included art, work and family. -

Modeling Radar Rainfall Estimation Uncertainties: Random Error Model A

Modeling Radar Rainfall Estimation Uncertainties: Random Error Model A. AghaKouchak1; E. Habib2; and A. Bárdossy3 Abstract: Precipitation is a major input in hydrological models. Radar rainfall data compared with rain gauge measurements provide higher spatial and temporal resolutions. However, radar data obtained form reflectivity patterns are subject to various errors such as errors in reflectivity-rainfall ͑Z-R͒ relationships, variation in vertical profile of reflectivity, and spatial and temporal sampling among others. Characterization of such uncertainties in radar data and their effects on hydrologic simulations is a challenging issue. The superposition of random error of different sources is one of the main factors in uncertainty of radar estimates. One way to express these uncertainties is to stochastically generate random error fields and impose them on radar measurements in order to obtain an ensemble of radar rainfall estimates. In the present study, radar uncertainty is included in the Z-R relationship whereby radar estimates are perturbed with two error components: purely random error and an error component that is proportional to the magnitude of rainfall rates. Parameters of the model are estimated using the maximum likelihood method in order to account for heteroscedasticity in radar rainfall error estimates. An example implementation of this approached is presented to demonstrate the model performance. The results confirm that the model performs reasonably well in generating an ensemble of radar rainfall fields with similar stochastic characteristics and correlation structure to that of unperturbed radar estimates. DOI: 10.1061/͑ASCE͒HE.1943-5584.0000185 CE Database subject headings: Rainfall; Simulation; Radars; Errors; Models; Uncertainty principles. Author keywords: Rainfall simulation; Radar random error; Maximum likelihood; Rainfall ensemble; Uncertainty analysis. -

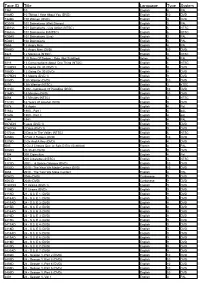

Tape ID Title Language Type System

Tape ID Title Language Type System 1361 10 English 4 PAL 1089D 10 Things I Hate About You (DVD) English 10 DVD 7326D 100 Women (DVD) English 9 DVD KD019 101 Dalmatians (Walt Disney) English 3 PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English 6 NTSC KD040 101 Dalmations (Live) English 3 PAL KD041 102 Dalmatians English 3 PAL 0665 12 Angry Men English 4 PAL 0044D 12 Angry Men (DVD) English 10 DVD 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English 3 NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian 4 PAL 6016 13 Conversations About One Thing (NTSC) English 1 NTSC 0189DN 13 Going On 30 (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 7080D 13 Going On 30 (DVD) English 9 DVD 0179DN 13 Moons (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 3050D 13th Warrior (DVD) English 10 DVD 6291 13th Warrior (NTSC) English 3 nTSC 5172D 1492 - Conquest Of Paradise (DVD) English 10 DVD 3165D 15 Minutes (DVD) English 10 DVD 6568 15 Minutes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 7122D 16 Years Of Alcohol (DVD) English 9 DVD 1078 18 Again English 4 Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English 4 pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English 4 pAL 1244 1941 English 4 PAL 0072DN 1Love (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0141DN 2 Days (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 3256D 2 Fast 2 Furious (DVD) English 10 DVD 5276D 2 Gs And A Key (DVD) English 4 DVD f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French 4 PAL X059D 20 30 40 (DVD) English 9 DVD 1304 200 Cigarettes English 4 Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 3172D 2001 - A Space Odyssey (DVD) English 10 DVD 3032D 2010 - The Year -

Kafka's Anti-Wagnerian Philosophy Of

53 (2/2019), pp. 109–123 The Polish Journal DOI: 10.19205/53.19.6 of Aesthetics Ido Lewit* “He Couldn’t Tell the Difference between The Merry Widow and Tristan and Isolde”: Kafka’s Anti-Wagnerian Philosophy of Music Abstract This essay exposes an anti-Wagnerian philosophy of music in Franz Kafka’s “Researches of a Dog” and “The Silence of the Sirens.” Themes of music, sound, and silence are over- whelmingly powerful in these stories and cannot be divorced from corporeal and visual aspects. These aspects are articulated in the selected texts in a manner that stands in stark opposition to Richard Wagner’s philosophy of music as presented in the composer’s sem- inal 1870 “Beethoven” essay. Keywords Richard Wagner, Franz Kafka, Philosophy of Music, Transcendence, Acousmatic Sound, Silence Max Brod, Franz Kafka’s close friend and literary executor, recalls in his bi- ography of the author that Kafka once said that “he couldn’t tell the differ- ence between The Merry Widow and Tristan and Isolde” (1995, 115). Brod evokes this memory in order to exemplify Kafka’s supposed lack of musi- cality. Indeed, for a German-speaking intellectual such as Kafka, not being able to differentiate Franz Lehár’s light operetta from Richard Wagner’s solemn, monumental music-drama would not simply be an example of unmusicality, but a symptom of cultural autism. While Brod’s recollection is sssssssssssss * Yale University Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures and the Program in Film and Media Studies Email: [email protected] 110 I d o L e w i t __________________________________________________________________________________________________ the only documented reference by Kafka to Wagner or his works,1 it does not necessarily follow that Kafka was unaware of Wagner’s views of music and its effects.